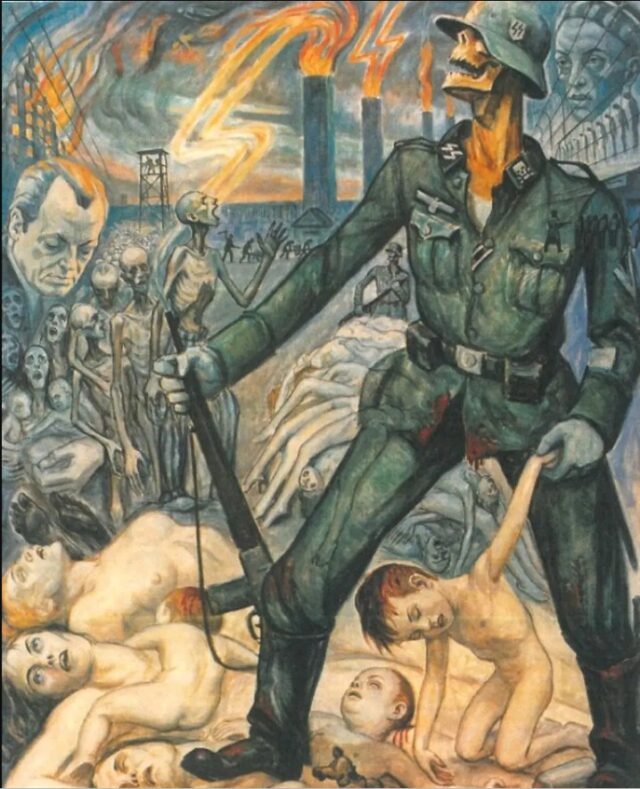

It’s forever being explained that this or that war or ‘conflict’ (a fun word to watch out for, generally meaning that the authorities and media recognise there’s something shameful or unequal in the situation) is complex and difficult. But even though the historical background, causes and contexts of wars are almost always complex, there’s one simple question that can clarify the course of events as they unfold: Is it ever acceptable to kill unarmed civilians who aren’t attacking you?

If the answer is yes, or anything that essentially means yes, then the arguments about right and wrong end and an eternal cycle of violence, death, reprisals and resentments is tacitly accepted. But if the answer is no – and to me it definitely is – then there’s a moral imperative not to let it happen.

The part of the question specifying who aren’t attacking you is crucial because realistically, escalating violence frequently ends in killing, whether or not that’s the original intention. Unless one is a Gandhi-style pacifist who thinks that being attacked is a signal to lie down and take it and that (to cite examples Gandhi used) the UK should have let Nazi Germany invade unopposed or that the Jews should have willingly delivered themselves up for extinction, the idea of being attacked and not reacting feels entirely unnatural, a practical impossibility, whatever your personal philosophy is. Not that that is any defence against most of the kind of attacks that happen in modern warfare.

Even as someone who believes it’s always wrong to kill unarmed civilians, it’s hard to resist applying that belief hypothetically to historical situations. It’s a pointless exercise because while it’s entertaining to imagine ‘sliding doors’ moments in history and extrapolate possible consequences from them, there’s no way of actually knowing how things would have panned out whatever the probabilities seem to have been. Plus, none of it can be changed now anyway. We don’t live in history, yet.

‘What if?’ is an irrelevant and frivolous question when applied to history, unless you happen to be writing a novel, making a film or inventing a time machine – but it’s a fundamental question about what is going to happen today.

It might seem obvious which war or conflict I have in mind while writing this, but although the most obvious guess may be the right one, I’m not avoiding naming names out of some kind of misguided sense of neutrality. I’m not trying to downplay sickening atrocities or genocides or to pretend that war crimes only matter when some people commit them but not others. The simplicity and universal applicability of the question is the whole point. Is it ever acceptable to kill unarmed civilians who aren’t currently attacking you? I don’t think so.

Everything is irrevocable once it has happened, but nothing is until then, so let’s not act as though some people are just destined to be collateral damage in wars as if it’s a fact of nature rather than the result of human choices and actions.