Any kind of masochism is (to non-masochists/collaborators) peculiar and difficult to understand; no less so when it is related to music; but I’m going to try to understand it anyway.

I have isolated three main areas which can be loosely classified under the ‘masochistic’ heading, but there may well be more:

1. Self-consciously unpleasant music which is “enjoyed” (or just enjoyed; a subtle but perhaps important difference) for its intentionally unpleasant/disturbing/unsettling or harsh sound

2. Music which is humorously/ironically enjoyed for its perceived awfulness*

3. Non-unpleasant music which is listened to specifically for its upsetting/depressing or negative emotional effect

Uniting all of these is the fact that they are not everyday listening (for me anyway), but in are special music which retains its potency by being indulged in only occasionally and when prepared for the physical (tinnitus) or mental (lachrymose) consequences.

*aka ‘guilty pleasures’ of course; but that is a whole other discussion; if guilt is an appropriate emotion for listening to music it would have to be something a bit less innocuous than I have in mind. ‘Embarrassing pleasures’ would be a more accurate and even more dodgy-sounding description

1. UNPLEASANT NOISES

The first category is very distinct from the other two; not only is the unpleasantness aural (and intentionally unpleasant), it is precisely the nastiness that appeals to the listener. Why that should be is mysterious; I have used the word ‘masochism’ in the title here, but only because everyone knows what it means and because I can’t think of a better term; but neither ‘sexual masochism disorder’, BDSM or so-called non-sexual masochism (“self-defeating personality disorder”) really functions in the same way as listening to, say The Rita (noise artist Sam McKinlay) or Gnaw Their Tongues.

Noise as (anti)music goes back at least as far as the Dada and Futurist movements of the early 20th century (on the left is Luigi Russolo with one of his Futurist instruments), but on the whole (I think) it’s true that the noise that was created, though fascinating to hear, was more about the process of composing and rule-breaking than listening for pleasure. The same may be true of a lot of experimental noise since then, with classic albums such as Yoko Ono’s Yoko Ono/Plastic Ono Band and Lou Reed’s Metal Machine Music probably being far more frequently owned than enjoyed. Various musique concréte and other avant garde pieces have the same kind of status, being performed perhaps more for historical/academic (albeit interesting) reasons rather than for the purpose of actual entertainment (which is not of course to say that people aren’t entertained by it).

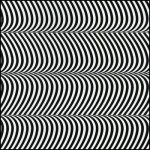

Noise: So what of semi-musical or non-musical noise like Merzbow or just plain ugly music? It’s hard to say where the appeal lies, but with pure noise it seems to be at least partly visceral. It has an immediate, emotional impact; it has nothing to do with traditional musical qualities such as melody, catchiness or even memorable-ness, since it’s possible to listen to the abstract noise of (for example)  Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so.

Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so.

At the same time, a quality that pure noise shares with more traditional music is that it can noticeably affect the mood of the listener, especially when played at a loud volume. Listening to pure noise can be much like watching ‘white noise’ on a TV screen; the endless movement may be random, but the mind will look for patterns and if it doesn’t find them, create them itself; pure noise often feels detailed in a way that very little actual music does. And it is enjoyable (the word covers a wide range of responses here) or unenjoyable (simpler) for as long as it engages the listener.

Ugly Music: What I shall call ugly music is sometimes easier to pin down; it is music, which means it follows certain structural rules which noise ignores, and the listener enjoys it for its ugliness or not at all. It is notable too that artists who aim for ugliness usually attempt the Wagnerian ideal of the gesamtkunstwerk or ‘total work of art’ where everything from the sound to the lyrics to the artwork contributes to the overall effect.

Ugly music probably began in the 60s with some of The Mothers of Invention’s more indigestible experiments (like Absolutely Free, which is perhaps more difficult than truly ugly), Captain Beefheart or the 17 minute churn of the Velvet Underground’s ‘Sister Ray’, but it came into its own in the artistically serious 1970s (see below) and, in a more populist and relatively lighthearted way with the advent of death metal in the 80s, specifically with albums like Reek of Putrefaction (1988) by Carcass. This classic album is ugly not only in the details of the music and presentation, but in the murky muddiness of its sound; a chance element caused by the cheapness of the recording, which makes some of the album sound like two or three different bands immersed in a swamp, simultaneously playing three different songs, When allied with the rasped vocals of Jeff Walker and the ridiculously deep ones of Bill Steer, this churning noise makes for a disorientating but strangely addictive listening experience, which has something to do with the humour of its extremity (lyrical and musical) as well as the pure heaviness.

Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears.

Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears.

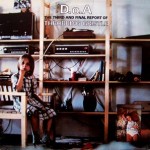

By contrast with death metal, the sheer ugliness of early industrial music exemplified by the work of Throbbing Gristle, seems designed not so much to shock or alienate with its extremity, so much as to shock and alienate with its familiarity, kind of a negative mirror image of the almost subliminal ambient music being pioneered around the same time in Eno’s Music For Airports.

By reflecting the greyness of the decaying industrial (edging into post-industrial) landscape and society that produced it, the corporate packaging and document-like title made TG’s debut album The Second Annual Report (1977) a masterpiece of grinding mundane-ness. In its way their music is  every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation

every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation  isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism.

isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism.

One of the cumulative effects of abrasive-sounding music has always been to spawn more accessible versions of abrasive-sounding music, in short, to make tunes out of it: noise rock, hardcore punk, death metal, grindcore, grunge, black metal, industrial pop music, techno, trance, drone, shoegaze; all bring a taste of ugliness to the masses in their own way and all are enjoyed, just like traditional pop/rock/soul/country/reggae etc etc etc, by people who like the tunes and like the songs. So they have little part to play in this particular discussion.

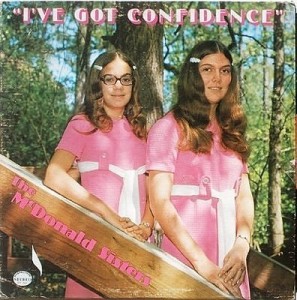

2. SO BAD IT’S POSSIBLE TO PRETEND IT’S GOOD

Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all.

Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all.

Since the 90s in fact, revelling in irony has become so commonplace and mainstream as not to be ironic anymore; at one time including an artist like Tom Jones in the lineup of a major indie rock festival was kind of a hipster joke that the audience was expected to be in on. Since then the line between alternative and mainstream has become blurred, not because mainstream music has become more adventurous, but because ‘alternative’ music became popular and thus blander and more geared towards commercial success and because the mainstream media discovered people they had actually heard of at these oft-derided hippy festivals. The amusingly mainstream guest act at (for example) Glastonbury or T in the Park has almost imperceptibly become the headlining act; no accident, since these artists are usually household names which therefore guarantee ticket sales in a way that even a medium-big indie rock band isn’t.

Nowadays, to have the same kind of kitsch shock value as including Tom Jones in an indie festival once had, you would have to put someone like Gary Glitter or Rolf Harris (an original ironic festival guest, strange to remember) on the stage, doubling the irony and making the whole experience extremely uncomfortable for all concerned. Despite the weird Ballardian/Coum Transmissions echo this experience this might present, it’s probably best not to.

3. NOW THAT’S WHAT I CALL MISERABLE MUSIC

This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.

This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.

In modern popular music there are many kinds of sad songs, but from a personal point of view (narrowing it down to music I actually like) there are two;

songs which express the unhappiness of the performer

songs (which may or may not be sad in themselves) which make the listener (me) feel unhappy.

Both of these kinds of songs may actually be very pleasant in an aural sense, so only the latter are strictly relevant here. But – outside of the funereal situation mentioned above – why would someone intentionally listen to music that makes them sad?

There are probably as many reasons as there are people, but two big ones: to make you feel better or to make you feel worse.

A lot of interesting research has been carried out on the restorative power of sad music, so I wont say too much about that. The blues (and early country music too) is a classic example – intended not just as an outlet for the woes of the artist her or himself, but as a sharing of universal wretchedness that brings the relief of empathy/recognition – and it does seem to have a regenerative quality (a kind of earthly parallel to the redemptive power of gospel music) that makes it essentially uplifting in all but the most desolate examples.

Music to make you feel worse is more problematic, but wanting to hear sad music that deepens your depression is a fairly common phenomenon, especially among adolescents. The logic of the blues is that something that reflects your mood or encapsulates your own troubles is a kind of comfort, but it’s also true that brooding on one’s unhappiness can deepen that mood; that one can indulge in misery. Why? Because people are strange and self-pity answers some deep-seated psychological need? Perhaps it is a real kind of masochism after all…

A short, personal masochistic playlist

UNPLEASANT (these examples are all undeniably ‘not nice’, but are oddly exhilarating too)

1. Throbbing Gristle – D.o.A.

2. Painkiller – Guts of a Virgin

3. Merzbow – Pulse Demon

4. Mastery – Valis

5. Hijōkaidan – Duo

MUSIC IT HURTS ME (TO VARYING DEGREES) TO LIKE

1. Celine Dion – My Heart Will Go On

2. Samantha Fox – Touch Me

3. Yngwie J Malmsteen’s Rising Force – Now Is The Time

4. Focus – Hocus Pocus

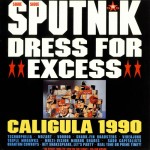

5. Sigue Sigue Sputnik – Dress for Excess

MISERABLE MUSIC FOR WALLOWING IN

1. The Smiths – I Know It’s Over

2. Cranes – Tomorrow’s Tears

3. Daniel Johnston – I Remember Painfully (plus most of Yip/Jump Music)

4. Adam Cohen – Beautiful

5. Red House Painters – Katy Song

Draining; that’s probably enough misery for now…

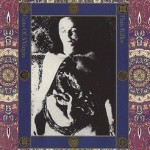

It’s not National, to my knowledge it’s rarely socialist, but it mostly is black metal; National Socialist Black Metal (hereafter, NSBM) annoys people by being ‘too evil’, or at least evil in the wrong way. As the snuff movie is to the horror movie, it seems, NSBM is to BM. There are a couple of flaws in this analogy; firstly, it suggests that black metal in general is, like horror movies, some kind of fantasy (which it certainly often is, but isn’t necessarily) and secondly, that NSBM isn’t some kind of fantasy (see previous parentheses). The Nazis of World War 2 represent the ‘ultimate evil’ to people of the post-war generations because whereas even the worst serial killers of the 20th century ‘worked’ on an individual, localised scale, the Nazis made murder into an ideology and ultimately an industry. That is, they functioned in ways that are relevant and relate-able to the daily lives and experiences of most people; but in bringing that mundane quality to extermination; ‘death factories’ they ultimately created something more frightening than a lone maniac. So is Nazi black metal the embodiment of that famously banal evil and therefore the ultimate in musical terrorism? Hmm, possibly not but let’s see…

It’s not National, to my knowledge it’s rarely socialist, but it mostly is black metal; National Socialist Black Metal (hereafter, NSBM) annoys people by being ‘too evil’, or at least evil in the wrong way. As the snuff movie is to the horror movie, it seems, NSBM is to BM. There are a couple of flaws in this analogy; firstly, it suggests that black metal in general is, like horror movies, some kind of fantasy (which it certainly often is, but isn’t necessarily) and secondly, that NSBM isn’t some kind of fantasy (see previous parentheses). The Nazis of World War 2 represent the ‘ultimate evil’ to people of the post-war generations because whereas even the worst serial killers of the 20th century ‘worked’ on an individual, localised scale, the Nazis made murder into an ideology and ultimately an industry. That is, they functioned in ways that are relevant and relate-able to the daily lives and experiences of most people; but in bringing that mundane quality to extermination; ‘death factories’ they ultimately created something more frightening than a lone maniac. So is Nazi black metal the embodiment of that famously banal evil and therefore the ultimate in musical terrorism? Hmm, possibly not but let’s see…