Remembering 1984 as someone who was a child then, I find that although the clocks didn’t strike thirteen, the year – as encapsulated by two specific and very different but not unconnected childhood memories, as we’ll see – is almost as alien nowadays as Orwell’s Airstrip One. Of course, I know far more now about both 1984 and Nineteen Eighty-Four than I did at the time. I was aware – thanks mostly I think to John Craven’s Newsround – of the big, defining events of the year.

I knew, for instance about the Miners’ Strike and the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, but they didn’t have anything like the same impact on me personally as Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. I remember Zola Budd tripping or whatever it was at the Olympics and Prince Harry being born, but they weren’t as important to me as Strontium Dog or Judge Dredd. Even Two Tribes by Frankie Goes to Hollywood made a bigger impression on me than most of the big news events, despite the fact that I didn’t like it. My favourite TV show that year was probably Grange Hill – and here we go.

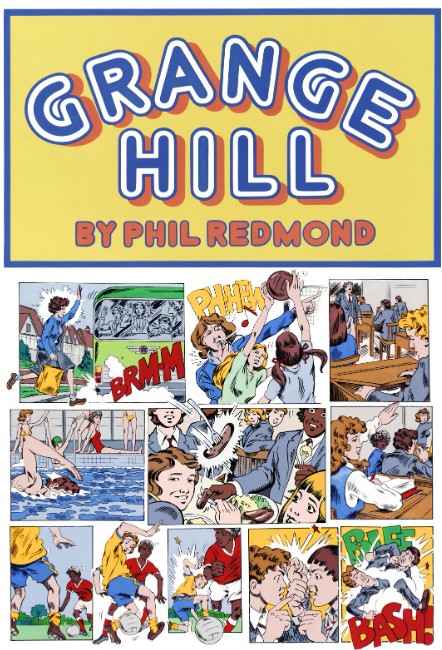

Grange Hill, essentially a kids’ soap opera set in a big comprehensive high school in London, ran for 30 years and I recently discovered that the era of it that I remember most fondly – the series’ that ran from 1983-6 – is available on YouTube. When I eventually went to high school later in the 80s, my first impression of the school was that it was like Grange Hill, and now I find that despite the silliness and melodrama, Grange Hill still reflects the reality, the look and the texture of my high school experience in the 80s with surprising accuracy.

But anyway, watching old Grange Hill episodes out of nostalgia, I was struck by how good it seems in the context of the 2020s, despite the obvious shortcomings of being made for children. Check out this scene from series seven, episode five, written by Margaret Simpson and aired in January of 1984. In among typical story arcs about headlice and bullying, the Fifth form class (17 year olds getting towards the end of their time at school) get the opportunity to attend a mock UN conference with representatives from other schools. In a discussion about that, the following exchange occurs between Mr McGuffy (Fraser Cains) and his pupils Suzanne Ross (Susan Tully), Christopher “Stewpot” Stewart (Mark Burdis), Claire Scott (Paula-Ann Bland) and Glenroy (seemingly of no last name) (Steven Woodcock). It’s worth noting that this was the year before Live Aid.

Suzanne: [re. the UN]:"It's about as effective as the school council." Mr McGuffy: "Oh well I wouldn't quite say that. The UN does some excellent work - UNESCO, the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the UN Peacekeeping force..." [...] Claire: "What's the conference gonna be about?" Mr McGuffy: "The world food problem. There was a real UN conference on this topic ten years ago..” Glenroy: "Didn't solve much then, did they? Millions of people still starvin'" Stewpot: ”Yeah that's cos they ain't got no political clout to do anything about it though, ain't it" Glenroy: ”Naw man, it's because the rich countries keep them that way” Suzanne: “The only chance a poor country's got is if it's got something we want” Glenroy: “That's right - they got something the west wants and they'd better watch out because the west starts to mess with their government." Mr McGuffy: "Well it's clear from what you've all said so far that you're interested in the sort of issues that will be discussed that weekend..."

It’s not too much of an exaggeration to say that that is a more mature political discussion than is often heard on Question Time in 2025. Interestingly, it’s not an argument between left and right as such, but between standard, humanitarian and more radical left-wing viewpoints. Needless to say, if it was presented on a TV show that’s popular with ten year-olds nowadays, a certain demographic would be foaming at the mouth about the BBC indoctrinating the young with “wokeness.” But as a kid this sort of discussion didn’t at all mar my enjoyment of the show – naturally there’s also a lot of comedic stuff in the series about stink bombs and money-making schemes, but one of the reasons that Grange Hill remained popular (and watchable for 8 year-olds and 15 year-olds alike) for so many years was that it refused to talk down to its audience.

The way the writers tackled the obvious big themes – racism, sexism, parents getting divorced, bullying, gangs, sex education etc – are impressive despite being, quite broad, especially when the younger pupils are the focus of the storyline, but what makes a bigger impression on me now is the background to it all. It’s a little sad – though true to Thatcher’s Britain – to see through all this period the older pupils’ low-level fretting about unemployment and whether it’s worth being in school at all.

And maybe they were right. In 1984, when Suzanne and Stewpot were 17, a fellow Londoner who could in a parallel universe have been in the year above them at Grange Hill was the 18-year-old model Samantha Fox. That year, she was The Sun newspaper’s “Page 3 Girl of the Year.” She had debuted as a topless model for the paper aged 16, which is far more mind boggling to a nostalgic middle-aged viewer of Grange Hill than it would have been to me at the time. Presumably, some parts of the anti-woke lobby would not mind Sam’s modelling as much as they would mind the Grange Hill kids’ political awareness, but who knows?

Naturally, the intended audience for Page 3 wasn’t Primary School children – but everybody knew who Sam Fox was and in the pre-internet, 4-channel TV world of 80s Britain he had a level of fame far beyond that of any porn star 40 years later (arguments about whether or not Page 3 was porn are brain-numbingly stupid, so I won’t go there; and anyway, I don’t mean porn to be a derogatory term). Anyway, Sam (she’ll always be “Sam” to people who grew up in the 80s) and her Page 3 peers made occasional accidental appearances in the classroom, to general hilarity, when the class was spreading old newspapers on our desks to prepare for art classes. It was also pretty standard then to see the “Page Three Stunnas” (as I think The Sun put it) blowing around the playground or covering a fish supper. It wasn’t like growing up with the internet, but in its own way the 80s was an era of gratuitous nudity.

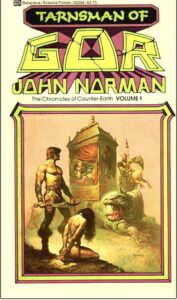

Meanwhile, on Page Three of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith – who is, shockingly, a few years younger than I am now – is trying to look back on his own childhood to discern whether things were always as they are now:

“But it was no use, he could not remember: nothing remained of his childhood except a series of bright-lit tableaux, occurring against no background and mostly unintelligible.” George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) P.3 – New Windmill edition, 1990

By contrast, some of the roots of 2025 are plain to see in 1984, despite the revolution of the internet that happened halfway between then and now. As the opposing poles of the Grange Hill kids and The Sun demonstrate, there were tensions in British society which would never so far be resolved, but they would come to some kind of semi-conclusion at the end of the Thatcher era when when ‘Political Correctness,’ the chimerical predecessor of the equally chimerical ‘Woke’ began to work in its unpredictable (but I think mostly positive) ways.

Most obviously, Page 3 became ever more controversial and was toned down (no nipples) and then vanished from the tabloids altogether for a while (though in the 90s the appearance of “lads’ mags” which mainstreamed soft porn made the death of Page 3 kind of a pyrrhic victory.) More complicatedly, the kind of confrontational storylines about topics like racism that happened in kids shows in the 80s became a little more squeamish, to the point where (for entirely understandable reasons) racist bullies on kids’ shows would rarely use actual racist language and then barely appear at all, replaced by positivity in the shape of more inclusive casting and writing. All of which became pretty quaint as soon as the internet really took off.

So, that was part of the 1984 that I remember; what Orwell would have made of any of it I don’t know. It wasn’t his nineteen eighty-four, which might have pleased him. For me, it all looks kind of extreme but also refreshingly straightforward, though I’m sure I only think so because I was a child. It’s all very Gen-X isn’t it?

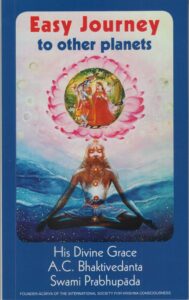

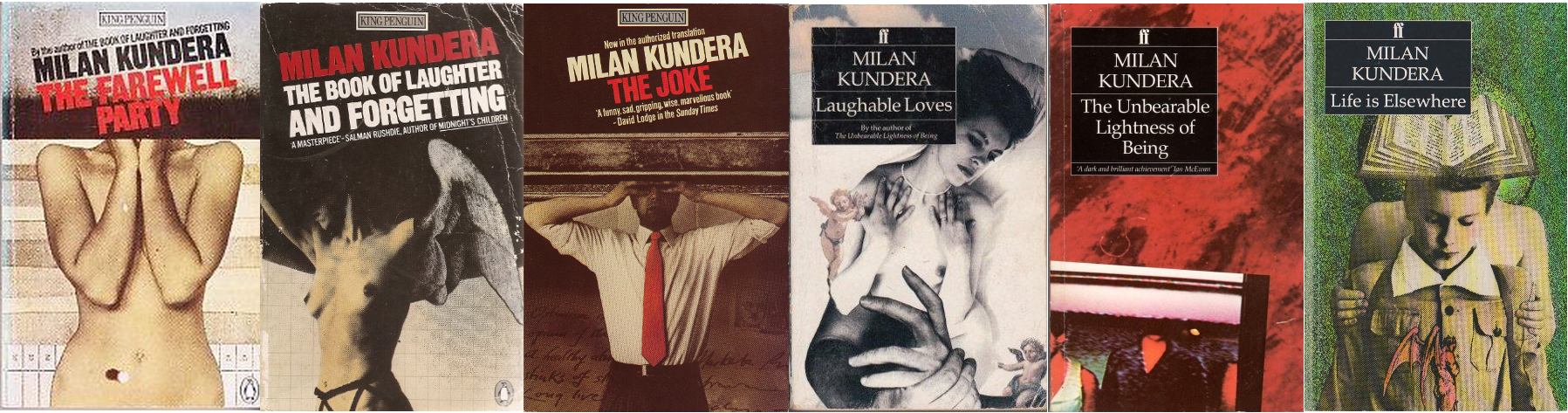

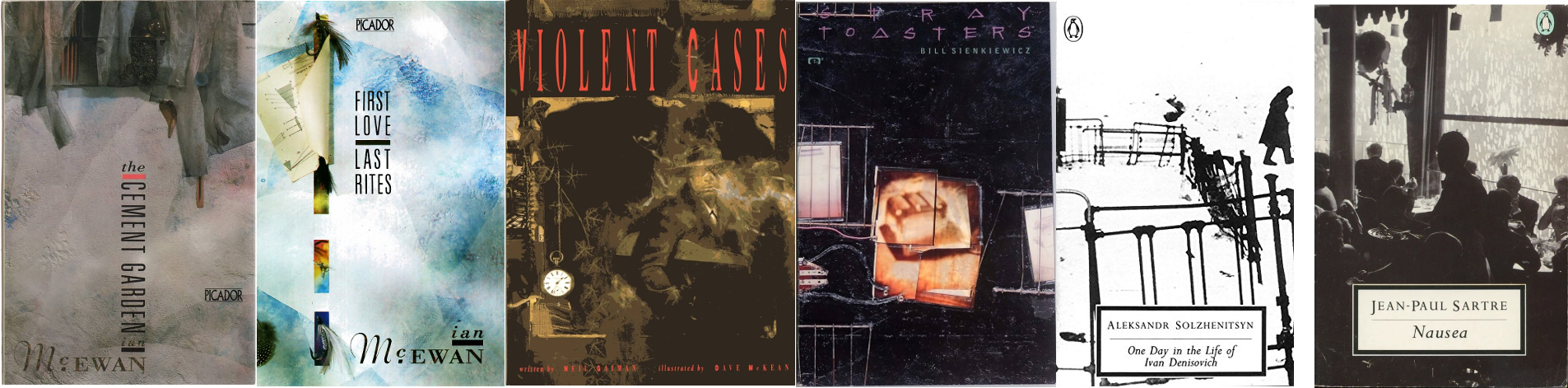

Why is it painful to get rid of books? Pompously, because the books you own are a reflection of yourself; of skins shed and personalities outgrown and discarded, and in a way a direct line back to your (possibly alarming) former selves with their sometimes alien tastes and enthusiasms.* Less pompously, because in general, I want more books, not fewer. I can’t think of an occasion when I got rid of a book simply because I didn’t like or just didn’t want it, though I’m sure it’s happened. And so, for decades I still owned (and may still have somewhere) the little red Gideons Bible that was given out to pupils when starting high school (do they still do that?). Its bookplate (ex-libris? Both terms seem very archaic) hints strongly at the typical kind of 12 year old boy that it was given to: Name: William Pinfold Form: human. Similarly, I may still have the books given to me in the street by Hare Krishna followers, which seems not to happen now but was a frequent enough thing in the early 90s that I can still remember without checking** that they were credited to and/or consisted of teachings by “His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami.” They often had nice, pleasingly psychedelic cover paintings but were invariably disappointing to try to read because, even when they had amazing titles like Easy Journey to Other Planets, they were all about Krishna consciousness – who knew?. But these are books that would be impossible to replace (in a personal sense; easy enough to get hold of different copies of them). More complicatedly – and just annoyingly, with space at a premium, I have multiple copies of some favourite books and will probably buy even more copies of them, if I come across them with covers that I like but don’t have and if they are cheap.

Why is it painful to get rid of books? Pompously, because the books you own are a reflection of yourself; of skins shed and personalities outgrown and discarded, and in a way a direct line back to your (possibly alarming) former selves with their sometimes alien tastes and enthusiasms.* Less pompously, because in general, I want more books, not fewer. I can’t think of an occasion when I got rid of a book simply because I didn’t like or just didn’t want it, though I’m sure it’s happened. And so, for decades I still owned (and may still have somewhere) the little red Gideons Bible that was given out to pupils when starting high school (do they still do that?). Its bookplate (ex-libris? Both terms seem very archaic) hints strongly at the typical kind of 12 year old boy that it was given to: Name: William Pinfold Form: human. Similarly, I may still have the books given to me in the street by Hare Krishna followers, which seems not to happen now but was a frequent enough thing in the early 90s that I can still remember without checking** that they were credited to and/or consisted of teachings by “His Divine Grace A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami.” They often had nice, pleasingly psychedelic cover paintings but were invariably disappointing to try to read because, even when they had amazing titles like Easy Journey to Other Planets, they were all about Krishna consciousness – who knew?. But these are books that would be impossible to replace (in a personal sense; easy enough to get hold of different copies of them). More complicatedly – and just annoyingly, with space at a premium, I have multiple copies of some favourite books and will probably buy even more copies of them, if I come across them with covers that I like but don’t have and if they are cheap.

sophisticated, articulate, menacing but not unfriendly. A few years later, when I began to read

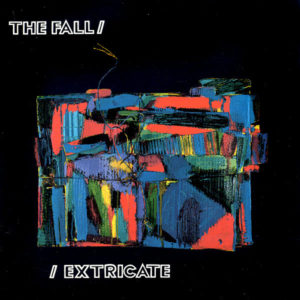

sophisticated, articulate, menacing but not unfriendly. A few years later, when I began to read  And that’s just the lyrics; another thing about The Fall that made an impression on me early on was that, although MES was incredibly fussy and perfectionist about the band’s music, he wasn’t snobbish in the usual way; no tune, if it was catchy, was too silly for Mark E. Smith. Think of the speedy but somehow miniature-sounding rock guitar on ‘Underground Medicine‘ or loping, bouncy beat to ‘Gramme Friday‘ or the oddly jaunty, countryish ‘Fit And Working Again‘. or the kazoo on ‘The North Will Rise Again‘– this was ‘angular’ (the definitive descriptive term for late 70s/early 80s UK indie rock) if you like, but it was not standard ‘post-punk’ music, nor was it (as it could easily have been) twee in that beloved ramshackle UK indie/C86 kind of way. Perhaps because Mark E. Smith was not (99% of the time) a melodic singer, the band could play anything behind him and it sounded right. When, at the beginning of one of my favourite songs, ‘Slates‘, MES shouts ‘this is the definitive rant‘ he’s nailing part of the charm of his work. As long as the rant was in place, no tune was too small, too jingly or too silly to make something worthwhile out of.

And that’s just the lyrics; another thing about The Fall that made an impression on me early on was that, although MES was incredibly fussy and perfectionist about the band’s music, he wasn’t snobbish in the usual way; no tune, if it was catchy, was too silly for Mark E. Smith. Think of the speedy but somehow miniature-sounding rock guitar on ‘Underground Medicine‘ or loping, bouncy beat to ‘Gramme Friday‘ or the oddly jaunty, countryish ‘Fit And Working Again‘. or the kazoo on ‘The North Will Rise Again‘– this was ‘angular’ (the definitive descriptive term for late 70s/early 80s UK indie rock) if you like, but it was not standard ‘post-punk’ music, nor was it (as it could easily have been) twee in that beloved ramshackle UK indie/C86 kind of way. Perhaps because Mark E. Smith was not (99% of the time) a melodic singer, the band could play anything behind him and it sounded right. When, at the beginning of one of my favourite songs, ‘Slates‘, MES shouts ‘this is the definitive rant‘ he’s nailing part of the charm of his work. As long as the rant was in place, no tune was too small, too jingly or too silly to make something worthwhile out of. lot of it, and it was mostly pretty affordable, especially the stuff from the band’s then slightly maligned, now justly celebrated mid-80s period of relative commercial success. In itself, that success was odd and underlined just how unique the band, and specifically Smith’s vision, was. I loved that Mark E. Smith saw nothing elitist or strange about working with a ballet company, or in writing for the theatre and working with ‘serious’ artists and yet the people I knew who derided Morrissey as being “poncy” never seemed to think that about MES. The fact that he refused to separate the ‘high’ arts from his work with The Fall was so powerful. Everyone knows, for example, that Brian May is an astrophysicist, but imagine if astrophysics had somehow been indivisible from his work with Queen; they would have been far a more peculiar and far less successful, but also (with no offence intended to the band or its members) probably more interesting band.

lot of it, and it was mostly pretty affordable, especially the stuff from the band’s then slightly maligned, now justly celebrated mid-80s period of relative commercial success. In itself, that success was odd and underlined just how unique the band, and specifically Smith’s vision, was. I loved that Mark E. Smith saw nothing elitist or strange about working with a ballet company, or in writing for the theatre and working with ‘serious’ artists and yet the people I knew who derided Morrissey as being “poncy” never seemed to think that about MES. The fact that he refused to separate the ‘high’ arts from his work with The Fall was so powerful. Everyone knows, for example, that Brian May is an astrophysicist, but imagine if astrophysics had somehow been indivisible from his work with Queen; they would have been far a more peculiar and far less successful, but also (with no offence intended to the band or its members) probably more interesting band. Although most of my favourite Fall albums are the early ones (especially Dragnet, Grotesque (After The Gramme) and Hex Enduction Hour) those 80s albums with the Mark and Brix-led lineup(s), especially The Wonderful and Frightening World Of The Fall are pretty unassailable and perhaps the least overtly commercial ‘commercial’ period of any band I can think of. The band stayed good though, and although I am not a Fall completist (a vocation rather than a hobby) I’ve found that any Fall record one picks up will have something great on it; and there aren’t many bands with a 40 year career you can say that about.

Although most of my favourite Fall albums are the early ones (especially Dragnet, Grotesque (After The Gramme) and Hex Enduction Hour) those 80s albums with the Mark and Brix-led lineup(s), especially The Wonderful and Frightening World Of The Fall are pretty unassailable and perhaps the least overtly commercial ‘commercial’ period of any band I can think of. The band stayed good though, and although I am not a Fall completist (a vocation rather than a hobby) I’ve found that any Fall record one picks up will have something great on it; and there aren’t many bands with a 40 year career you can say that about.