Everybody has their comforts, but after trying to analyse some of my own to see why they should be comforting I’ve pretty much come up with nothing, or at least nothing really to add to what I wrote a few years ago; “comforting because it can be a relief to have one’s brain stimulated by something other than worrying about external events.” But that has nothing to do with what it is that makes the specific things comforting. Like many people, I have a small group of books and films and TV shows and so on that I can read or watch or listen to at almost any time, without having to be in the mood for them, and which I would classify as ‘comforting.’ They aren’t necessarily my favourite things, and they definitely weren’t all designed to give comfort, but obscurely they do. But what does that mean or signify? I’ve already said I don’t know, so it’s not exactly a cliffhanger of a question, but let’s see how I got here at least.

I’ve rewritten this part so many times: but in a way that’s apposite. I started writing it at the beginning of a new year, while wars continued to rage in Sudan and Ukraine and something even less noble than a war continued to unfold in Gaza, and as the world prepared for an only partly precedented new, oligarchical (I think at this point that’s the least I can call it) US government. Writing this now, just a few months later, events have unfolded somewhat worse than might have been expected. Those wars still continue and despite signs to the contrary, the situation in Gaza seems if anything bleaker than before. That US administration began the year by talking about taking territory from what had been allies, supporting neo-Nazi and similar political groups across the world, celebrating high profile sex offenders and violent criminals while pretending to care about the victims of sex offenders and violent criminals, and has gone downhill from there.

In the original draft of this article I predicted that this Presidential term would be an even more farcical horrorshow (not in the Clockwork Orange/Nadsat sense, although Alex and his Droogs might well enjoy this bit of the 2020s; I suppose what I mean is ‘horror show’) than the same president’s previous one, and since it already feels like the longest presidency of my lifetime I guess I was right. So, between the news and the way it never stops coming (hard to remember, but pre-internet ‘the news’ genuinely wasn’t so relentless or inescapable, although events presumably happened at the same rate) it’s important to find comfort somewhere. The obvious, big caveat is that one has to be in a somewhat privileged position to be able to find comfort in the first place. There are people all over the world – including here in the UK – who can only find it, if at all, in things like prayer or philosophy; but regardless, not being so dragged down by current events that you can’t function is kind of important however privileged you are, and even those who find the whole idea of ‘self-love’ inimical have to find comfort somewhere.

But where? And anyway, what does comfort even mean? Well, everyone knows what it means, but though as a word it seems fluffy and soft (Comfort fabric softener, the American word “comforter” referring to a quilt), it actually comes from the Latin “com-fortis” meaning something like “forceful strength” – but let’s not get bogged down in etymology again.

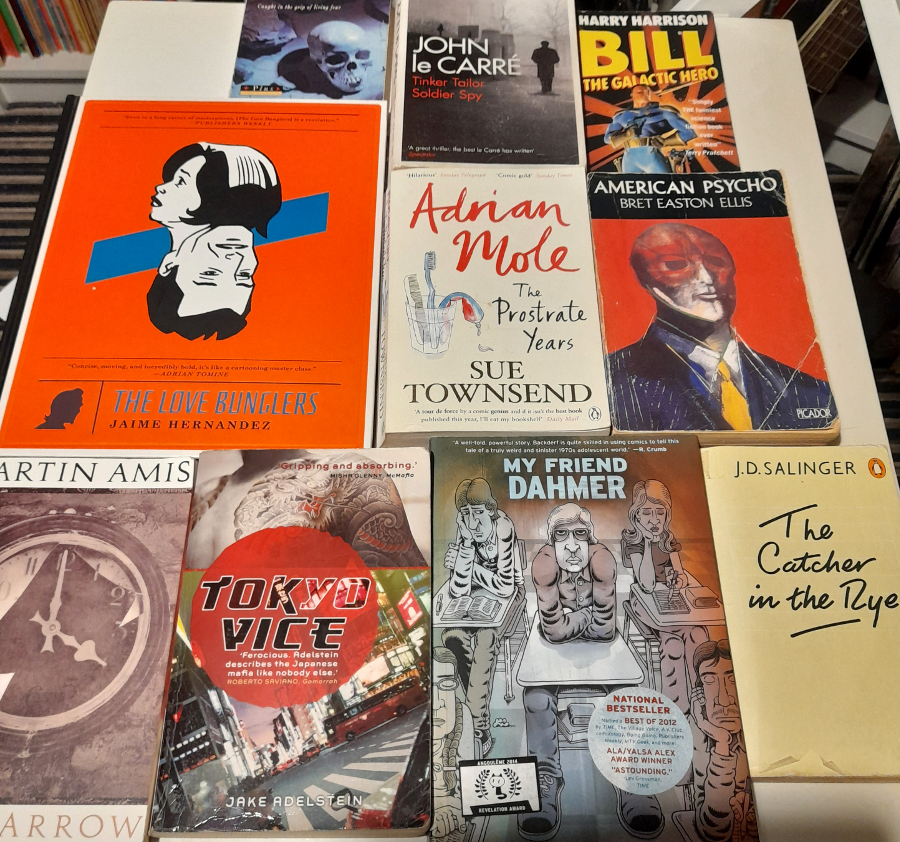

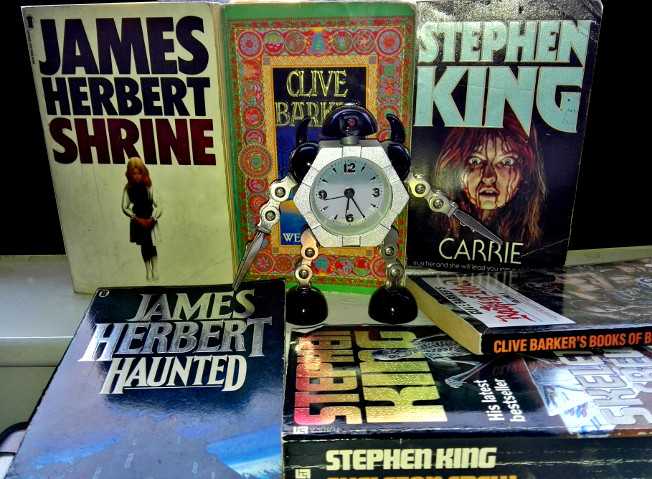

But wherever you find it, the effect of comfort has a mysterious relationship to the things that actually offer us support or soothe our grief and mental distress. Which is not obvious; normally if you desire a specific reaction (laughter, fear, excitement) you turn to a particular source. If you want to laugh, you turn to something funny, which is obviously subjective but never mind. Sticking to books, because I can – for me lots of things would work, if I want to be amused, Afternoon Men by Anthony Powell, Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole books and, less obviously, The Psychopath Test by Jon Ronson always raise a smile or a laugh. Conversely, if you want to be scared or disgusted (in itself a strange and obscure desire, but a common one), you’d probably turn to horror, let’s say HP Lovecraft, Stephen King’s IT or, less generic but not so different, Bret Easton Ellis’s American Psycho. But as you might have guessed if you’ve read anything else on this website, I’d probably list all of those books among my ‘comfort reads.’

But whatever I am reading, I’m not alone; people want ‘comfort reads’ and indeed there is a kind of comfort industry these days. Over the years it’s developed from poetry anthologies and books of inspirational quotes to more twee versions of the same thing. I think of books of the Chicken Soup for the Soul kind (I don’t think I made that up; if I recall my mother owned a little book of that title, full of ‘words of wisdom’ and comforting quotes) as a 90s phenomenon, but that might be wrong. But at some point that evolved into the more widespread ‘mindfulness’ industry (colouring books, crochet, apps, etc). Marketing-wise there have been phenomena like hygge (as far as I’ve seen books of the Chicken Soup type, but with more crossover into other areas, as with mindfulness) and, in Scotland at least, hygge rebranded, aggravatingly, as ‘coorie.’ In this context ‘coorie’ is a similar concept to ‘hygge’ but that’s not really how I’ve been used to hearing the word used through my life, so something like ‘A Little Book of Coorie‘ just doesn’t sound right. But maybe a book of hygge doesn’t either, if you grew up with that word?

People take comfort in pretty much anything that distracts them, so often the best kind of comfort is being active; walking, running, working or eating, and I understand that; nothing keeps you in the moment or prevents brooding like focusing on what you’re doing. But, unless you’re in a warzone or something, it’s when you aren’t busy that the world seems the most oppressive, and while running may keep you occupied, which can be comforting, it isn’t ‘comfortable’ (for me) in the usual sense of the word. Personally, the things I do for comfort are most likely to be the same things I write about most often, because I like them; reading, listening to music, watching films or TV.

Comfort reading, comfort viewing, comfort listening are all familiar ideas, and at first I assumed that the core of what makes them comforting must be their familiarity. And familiarity presumably does have a role to play – I probably wouldn’t turn to a book I knew nothing about for comfort, though I might read something new by an author I already like. Familiarity, though it might be – thinking of my own comfort reads – the only essential ingredient for something to qualify as comforting, is in itself a neutral quality at best and definitely not automatically comforting. But even when things are comforting, does that mean they have anything in common with each other, other that the circular fact of their comforting quality? Okay, it’s getting very annoying writing (and reading) the word comforting now.

Many of the books that I’d call my all-time favourites don’t pass the comfort test; that is, I have to be in the mood for them. I love how diverse and stimulating books like Dawn Ades’ Writings on Art and Anti-Art and Harold Rosenberg’s The Anxious Object are, but although I can dip into them at almost any time, reading an article isn’t the same as reading a book. There are not many novels I like better than The Revenge for Love or The Apes of God by Wyndham Lewis. They are funny and clever and mean-spirited in a way that I love and I’ve read them several times and will probably read them again; but I never turn to Lewis for comfort. He would probably be glad not to be a ‘comfort read,’ that has nothing (as far as I can tell) to do with the content of his books. Some of my ‘comfort reads’ are obvious, and in analysing them I can come up with a list of plausible points that make them comforting, but others less so.

In that obvious category are books I read when I was young, but that I can still happily read as an adult. There is an element of nostalgia in that I’m sure, and nostalgia is a complicated kind of comfort. I first read The Lord of the Rings in my early teens but, as I’ve written elsewhere, I had previously had it read to me as a child, so I feel like I’ve always known it. Obviously that is comforting in itself, but there’s also the fact that it is an escapist fantasy; magical and ultimately uplifting, albeit in a bittersweet way. The same goes for my favourites of Michael Moorcock’s heroic fantasy series. I read the Corum, Hawkmoon and Elric series’ (and various other bits of the Eternal Champion cycle) in my teens and though Moorcock is almost entirely different from Tolkien, the same factors (escapist fantasy, heroic, magical etc) apply.

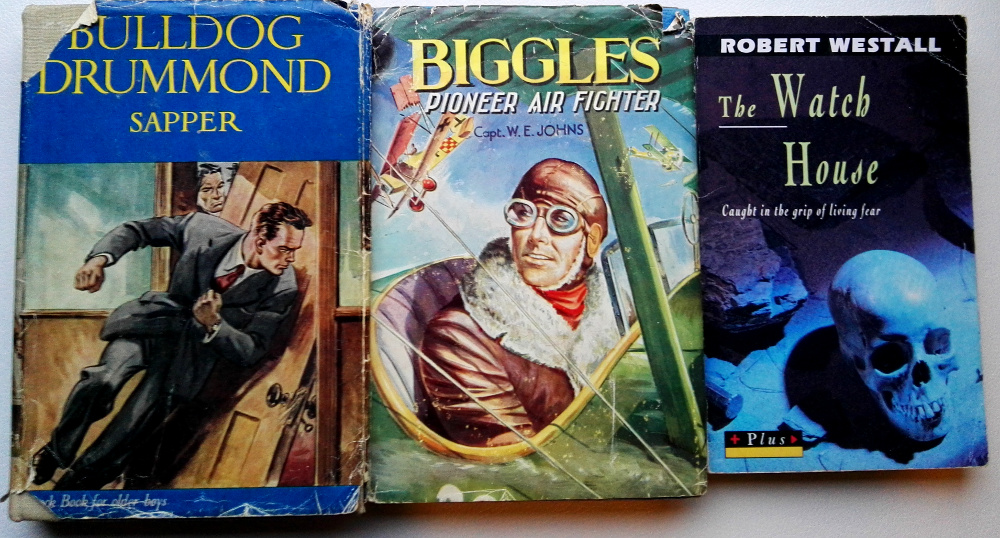

Even the Robert Westall books I read and loved as a kid, though they (The Watch House, The Scarecrows, The Devil on the Road, The Wind Eye, the Machine Gunners, Fathom Five) are often horrific, have the comforting quality that anything has if you loved it when you were 11. Not that the books stay the same; as an adult they are, surprisingly, just as creepy as I remembered, but I also notice things I didn’t notice then. Something too mild to be called misogyny, but a little uncomfortable nonetheless and, more impressively, characters that I loved and identified with now seem like horrible little brats, which I think is actually quite clever. But that sense of identification, even with a horrible little brat, has a kind of comfort in it, possibly.

The same thing happens with (mentioned in too many other things on this site) IT. A genuinely nasty horror novel about a shapeshifting alien that pretends to be a clown and kills and eats children doesn’t at first glance seem like it should be comforting. But if you read it when you were thirteen and identified with the kids rather than the monster, why wouldn’t it be? Having all kinds of horrible adventures with your friends is quite appealing as a child and having them vicariously via a book is the next best thing, or actually a better or at least less perilous one.

But those are books I read during or before adolescence and so the comforting quality comes to them naturally, or so it seems. The same might be true of my favourite Shakespeare plays, which I first read during probably the most intensely unhappy part of my adolescence – but in a weird, counterintuitive way, that adds to the sense of nostalgia.

Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole books are kind of in a category of their own. When I read the first one, Adrian was 13 and I would have been 11. And then, I read the second a year or so later, but the others just randomly through the years. I’m not sure I was even aware of them when they were first published, but the ones where Adrian is an adult are just as funny but also significantly more painful. It’s a strange thing to read about the adult life of a character you “knew” when you were both unhappy children. Although she had a huge amount of acclaim and success during her life, I’m still not sure Townsend gets quite the credit she’s due for making Adrian Mole a real person. Laughing at a nerdy teenager’s difficult adolescence and his cancer treatment as a still-unhappy middle-aged adult is a real imaginative and empathic achievement. Still; the comfort there could be in the familiar, not just the character but the world he inhabits. Adrian is, reading him as an adult (and as he becomes an adult) surprisingly nuanced; even though he’s uptight and conservative and in a way a little Englander and terminally unreliable as a teenager and loses none of those traits as an adult, you somehow know that you can count on him not to be a Nazi or misogynist, no small thing in this day and age.

But if Frodo and Elric and Adrian Mole are characters who I knew from childhood or adolescence, what about A Clockwork Orange, which I first read and immediately loved in my early 20s and which, despite the (complicatedly) happy ending could hardly be called uplifting? Or The Catcher in the Rye, which again I didn’t read until my 20s and have been glad ever since that I didn’t “do” it at school as so many people did. Those books have a lot in common with Adrian Mole, in the sense that they are first-person narratives by troubled teenagers. Not that Alex is “troubled” in the Adrian/Holden Caulfield sense. But maybe it’s that sense of a ‘voice’ that’s comforting? If so, what does that say about the fact that Crash by JG Ballard or worse, American Psycho is also a comfort read for me?

I read both of those novels in my 20s too, and immediately liked them, though not in the same way as The Catcher in the Rye. To this day, when I read that book, part of me responds to it in the identifying sense; that part of me will probably always feel like Holden Caulfield, even though I didn’t do the things he did or worry about ‘phonies’ as a teenager. I loved Crash from the first time I read the opening paragraphs but although there must be some sense of identification (it immediately felt like one of ‘my’ books) and although I have a lot of affection for Ballard as he comes across in interviews, I don’t find myself reflected in the text, thankfully. Same (even more thankfully) with American Psycho – Patrick Bateman is an engaging, very annoying narrator (more Holden than Alex, interestingly) and I find that as with Alex in A Clockwork Orange his voice feels oddly effortless for me to read. Patrick isn’t as nice(!) or as funny or clever as Alex, but still, there’s something about his neurotic observations and hilariously tedious lists that’s – I don’t know, not soothing to read, exactly, but easy to read. Or something. Hmm.

But if Alex, Adrian, Holden and Patrick feel real, what about actual real people? I didn’t read Jake Adelstein’s Tokyo Vice until I was in my early 30s, but it quickly became a book that I can pick up and enjoy it at any time. And yet, though there is a kind of overall narrative arc and even a sort of happy ending, that isn’t really the main appeal; and in this case it isn’t familiarity either. It’s episodic and easy to dip into (Jon Ronson’s books have that too and so do George Orwell’s Essays and Journalism and Philip Larkin’s Selected Letters, which is another comfort read from my 20s) The culture of Japan that Adelstein documents as a young reporter has an alien kind of melancholy that is somehow hugely appealing even when it’s tragic. Another true (or at least fact-based) comfort read, Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, which I only read in my 40s after meaning to read it ever since high school, has no business whatsoever being comforting. So why is it? I’m not getting any closer to an answer.

Predictability presumably has a role to play; as mentioned above, I wouldn’t read a book for the first time as ‘a comfort read’ and even though I said I might read a familiar author that way, it suddenly occurs to me that that is only half true. I would read Stephen King for comfort, but I can think of at least two of his books where the comfort has been undone because the story went off in a direction that I didn’t want it to. That should be a positive thing; predictability, even in genre fiction which is by definition generic to some extent, is the enemy of readability and the last thing you want is to lose interest in a thriller. I’ve never been able to enjoy whodunnit type thrillers for some reason; my mother loved them and they – Agatha Christie, Ngaio Marsh, Sue Grafton, even Dick Francis, were her comfort reads. Maybe they are too close to puzzles for my taste? Not sure.

So to summarise; well-loved stories? Sometimes comforting. Identifiable-with characters? Sometimes comforting. Authorial voices? This may be the only unifying factor in all the books I’ve listed and yet it still seems a nebulous kind of trait and Robert Westall has little in common with Sue Townsend or Bret Easton Ellis, or (etc, etc). So instead of an actual conclusion, I’ll end with a funny, sad and comforting quote from a very silly, funny but in some ways comforting book; Harry Harrison’s 1965 satirical farce Bill, the Galactic Hero. The book is in lots of ways horrific; Bill, an innocent farm boy, finds himself swept up into the space corps and a series of ridiculous and perilous adventures. The ending of the book is both funny and very bitter, but rewinding to an earlier scene where Bill has lost his left arm in combat but had a new one – a right arm, which belonged to his best friend, grafted on:

He wished he could talk to some of his old buddies, then remembered that they were all dead and his spirits dropped further. He tried to cheer himself up but could think of nothing to be cheery about until he discovered that he could shake hands with himself. This made him feel a little better. He lay back on the pillows and shook hands with himself until he fell asleep.

Harry Harrison, Bill the Galactic Hero, p.62 (Victor Gollancz, 1965)

It’s funny; the arrogance and certainty of youth is well-known, but I’m still very surprised to find it in myself. I have rarely met anyone less sure of themselves or more reticent than my late-teens/early-20s self, but that doesn’t come across at all, except in a few deliberately self-deprecating caveats, and there’s an infuriating cockiness to some of the writing that I not only don’t identify with, but really hate; what’s mortifying is that I was genuinely trying to think deeply about the issues I covered so shallowly. Oh well, I hope I wasn’t actually that obnoxious in everyday life, but who knows? (anyone who knew me). On the other hand, my actual views don’t seem to have changed as much as I would have expected. I was more of a libertarian, albeit a left-wing one then, perhaps a bit more pessimistic, but on the whole I would still find myself on the same side of most of the arguments I am making, which is reassuring.

It’s funny; the arrogance and certainty of youth is well-known, but I’m still very surprised to find it in myself. I have rarely met anyone less sure of themselves or more reticent than my late-teens/early-20s self, but that doesn’t come across at all, except in a few deliberately self-deprecating caveats, and there’s an infuriating cockiness to some of the writing that I not only don’t identify with, but really hate; what’s mortifying is that I was genuinely trying to think deeply about the issues I covered so shallowly. Oh well, I hope I wasn’t actually that obnoxious in everyday life, but who knows? (anyone who knew me). On the other hand, my actual views don’t seem to have changed as much as I would have expected. I was more of a libertarian, albeit a left-wing one then, perhaps a bit more pessimistic, but on the whole I would still find myself on the same side of most of the arguments I am making, which is reassuring.

the Mobile Library (itself a very 80s detail although I’m sure they still exist) and loving them, and, later in Primary School Robert Westall’s The Scarecrows, The Watch House, The Wind Eye and The Devil on the Road made a big impression on me (and still stand up well when read as an adult). As a devotee of the phenomenally successful Fighting Fantasy gamebook series, I recall being particularly impressed by the horror-themed House Of Hell, which was very different from the swords & sorcery (or sci fi) leanings of the rest of the series.

the Mobile Library (itself a very 80s detail although I’m sure they still exist) and loving them, and, later in Primary School Robert Westall’s The Scarecrows, The Watch House, The Wind Eye and The Devil on the Road made a big impression on me (and still stand up well when read as an adult). As a devotee of the phenomenally successful Fighting Fantasy gamebook series, I recall being particularly impressed by the horror-themed House Of Hell, which was very different from the swords & sorcery (or sci fi) leanings of the rest of the series.

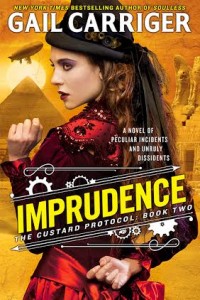

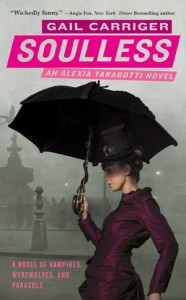

Soulless wasn’t Dawson’s Creek with vampires; the supernatural characters were, as with most modern/post-modern fiction, given a similar complexity to their human counterparts, but Carriger goes further, weaving the supernatural/natural worlds together in an ingenious yet extremely logical and historically-informed way. Part of what makes this so successful is that she placed her characters in a parallel version of the Victorian era, creating a society where vampires and werewolves, without sacrificing their predatory nature, exist alongside their mortal contemporaries as yet more finely nuanced layers in the already-complicated social hierarchy of Victorian Britain. If the Victorian era represents the height of the British preoccupation with social class and proper manners, these become even more crucial in Carriger’s world, where the correct way to interact with social superiors/inferiors includes people, possibly on both sides, whose politeness is the only thing preventing them from drinking your blood/eating you.

Soulless wasn’t Dawson’s Creek with vampires; the supernatural characters were, as with most modern/post-modern fiction, given a similar complexity to their human counterparts, but Carriger goes further, weaving the supernatural/natural worlds together in an ingenious yet extremely logical and historically-informed way. Part of what makes this so successful is that she placed her characters in a parallel version of the Victorian era, creating a society where vampires and werewolves, without sacrificing their predatory nature, exist alongside their mortal contemporaries as yet more finely nuanced layers in the already-complicated social hierarchy of Victorian Britain. If the Victorian era represents the height of the British preoccupation with social class and proper manners, these become even more crucial in Carriger’s world, where the correct way to interact with social superiors/inferiors includes people, possibly on both sides, whose politeness is the only thing preventing them from drinking your blood/eating you.