When I was a child there was music which was, whether you liked it or not, inescapable. I have never – and this is not a boast – deliberately or actively listened to a song by Michael Jackson, Madonna, Phil Collins, Duran Duran, Roxette, Take That, Bon Jovi, the Spice Girls… the list isn’t endless, but it is quite long. And yet I know some, or a lot, of songs by all of those artists. And those are just some of the household names. Likewise I have never deliberately listened to “A Horse With No Name” by America, “One Night in Bangkok” by Murray Head or “Would I Lie to You” by Charles & Eddie; and yet, there they are, readily accessible should I wish (I shouldn’t) to hum, whistle or sing them, or just have them play in my head, which I seemingly have little control over.

And yet, since the dawn of the 21st century, major stars come and go, like Justin Bieber, or just stay, like Ed Sheeran, Lana Del Rey or Taylor Swift, without ever really entering my consciousness or troubling my ears. I have consulted with samples of “the youth” to see if it’s just me, but no: like me, there are major stars that they have mental images of, but unless they have actively been fans, they couldn’t necessarily tell you the titles of any of their songs and have little to no idea of what they actually sound like. Logical, because they were no more interested in them than I was in Dire Straits or Black Lace; but alas, I know the hits of Dire Straits and Black Lace. And the idea of ‘the Top 40 singles chart’ really has little place in their idea of popular music. Again, ignorance is nothing to be proud of and I literally don’t know what I’m missing. At least my parents could dismiss Madonna or Boy George on the basis that they didn’t like their music. It’s an especially odd situation to find myself in as my main occupation is actually writing about music; but of course, nothing except my own attitude is stopping me from finding out about these artists.

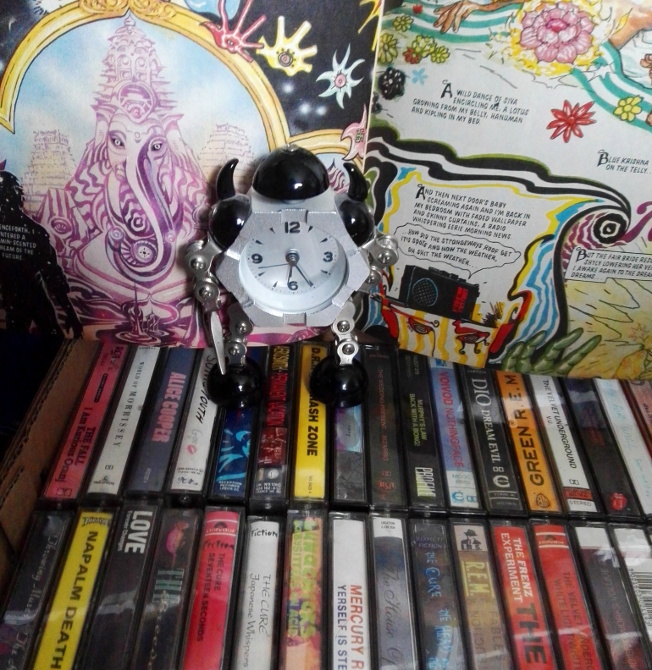

The fact is that no musician is inescapable now. Music is everywhere, and far more accessibly so than it was in the 80s or 90s – and not just new music. If I want to hear Joy Division playing live when they were still called Warsaw or track down the records the Wu-Tang Clan sampled or hear the different version of the Smiths’ first album produced by Troy Tate, it takes as long about as long to find them as it does to type those words into your phone. Back then, if you had a Walkman you could play tapes, but you had to have the tape (or CD – I know CDs are having a minor renaissance, but is there any more misbegotten, less lamented creature than the CD Walkman?) Or you could – from the 1950s onwards – carry a radio with you and listen to whatever happened to be playing at the time. I imagine fewer people listen to the radio now than they did even 30 years ago, but paradoxically, though there are probably many more – and many more specialised – radio stations now than ever, their specialisation actually feeds the escapability of pop music. Because if I want to hear r’n’b or metal or rap or techno without hearing anything else, or to hear 60s or 70s or 80s or 90s pop without having to put up with their modern-day equivalents, then that’s what I and anyone else will do. I have never wanted to hear “Concrete and Clay” by Unit 4+2 or “Agadoo” or “Come On Eileen” or “Your Woman” by White Town or (god knows) “Crocodile Shoes” by Jimmy Nail; but there was a time when hearing things I wanted to hear but didn’t own, meant running the risk of being subjected to these, and many other unwanted songs. As I write these words, “Owner of a Lonely Heart” by Yes, a song that until recently I didn’t know I knew is playing in my head.

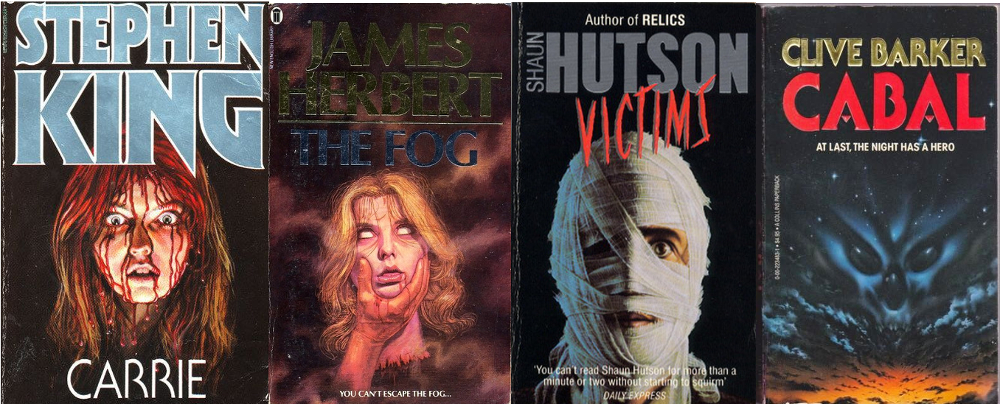

And so, the music library in my head is bigger and more diverse than I ever intended it to be. In a situation where there were only three or four TV channels and a handful of popular radio stations, music was a kind of lingua franca for people, especially for young people. Watching Top of the Pops on a Thursday evening, or later The Word on Friday was so standard among my age group that you could assume that most people you knew had seen what you saw; that’s a powerful, not necessarily bonding experience, but a bond of sorts, that I don’t see an equivalent for now, simply because even if everyone you know watches Netflix, there’s no reason for them to have watched the same thing at the same time as you did. It’s not worse, in some ways it’s obviously better; but it is different. Of course, personal taste back then was still personal taste, and anything not in the mainstream was obscure in a way that no music, however weird or niche, is now obscure, but that was another identity-building thing, whether one liked it or not.

Growing up in a time when this isn’t the case and the only music kids are subjected to is the taste of their parents (admittedly, a minefield) or fragments of songs on TV ads, if they watch normal TV or on TikTok, if they happen to use Tiktok, is a vastly different thing. Taylor Swift is as inescapable a presence now, much as Madonna was in the 80s, but her music is almost entirely avoidable and it seems probable that few teenagers who are entirely uninterested in her now will find her hits popping unbidden into their heads in middle age. But conversely, the kids of today are more likely to come across “Owner of a Lonely Heart” on YouTube than I would have been to hear one of the big pop hits of 1943 in the 80s.

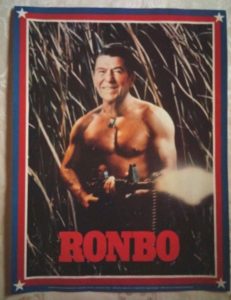

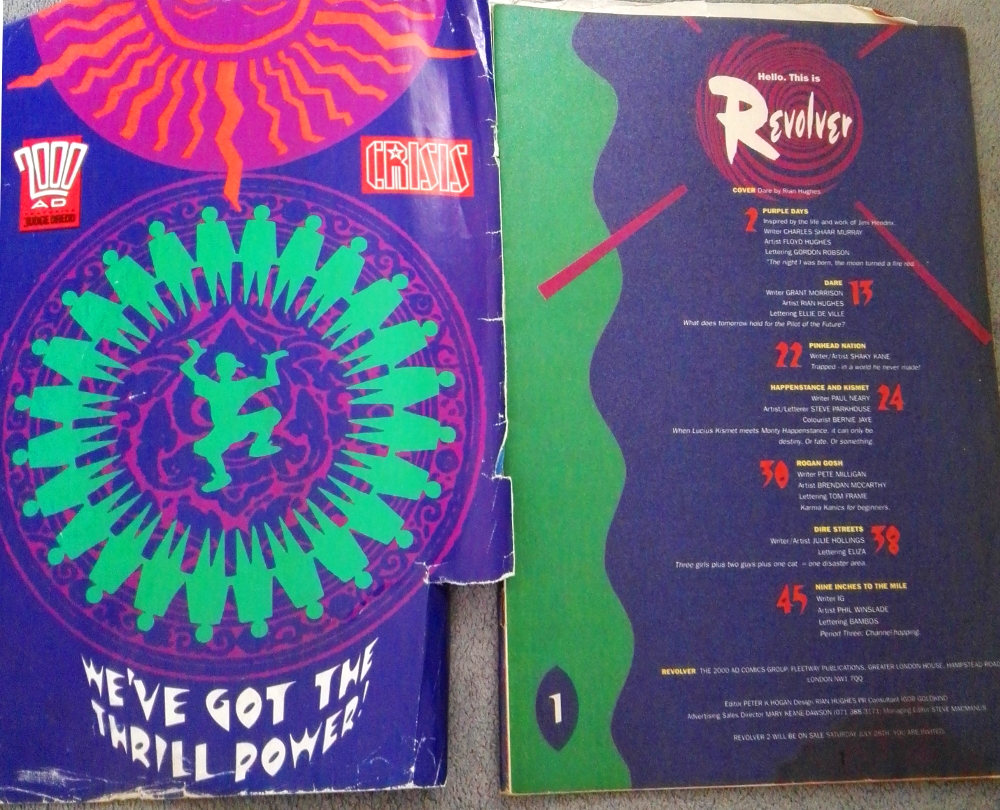

What this means for the future I don’t know; but surely its implications for pop-culture nostalgia – which has grown from its humble origins in the 60s to an all-encompassing industry, are huge. In the 60s, there was a brief fashion for all things 1920s and 30s which prefigures the waves of nostalgia that have happened ever since. But for a variety of reasons, some technical, some generational and some commercial, pop culture nostalgia is far more elaborate than ever before. We live in a time when constructs like “The 80s” and “The 90s” are well-defined, marketable eras that mean something to people who weren’t born then, in quite a different way from the 1960s version of the 1920s. Even back then, the entertainment industry could conjure bygone times with an easy shorthand; the 1960s version of the 1920s and 30s meant flappers and cloche hats and Prohibition and the Charleston and was evoked on records like The Beatles’ Honey Pie and seen onstage in The Boy Friend or in the cinema in Bonnie & Clyde. But the actual music of the 20s and 30s was mostly not relatable to youngsters in the way that the actual entertainment of the 80s and 90s still is. Even if a teenager in the 60s did want to watch actual silent movies or listen to actual 20s jazz or dance bands they would have to find some way of accessing them. In the pre-home video era that meant relying on silent movie revivals in cinemas, or finding old records and having the right equipment to play them on, since old music was then only slowly being reissued in modern formats. The modern teen who loves “the 80s” or “the 90s” is spoiled by comparison, not least because its major movie franchises like Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Ghostbusters and Jurassic Park are still around and its major musical stars still tour or at least have videos and back catalogues that can be accessed online, often for free.

Fashion has always been cyclical, but this feels quite new (which doesn’t mean it is though). Currently, culture feels not like a wasteland but like Eliot’s actual Waste Land, a dissonant kind of poetic collage full of meaning and detritus and feeling and substance and ephemera but at first glance strangely shapeless. For example, in one of our current pop culture timestreams there seems to be a kind of 90s revival going on, with not only architects of Britpop like the Gallagher brothers and Blur still active, but even minor bands like Shed Seven not only touring the nostalgia circuit but actually getting in the charts. Britpop was notoriously derivative of the past, especially the 60s and 70s. And so, some teenagers and young adults (none of these things being as pervasive as they once were) are now growing up in a time when part of ‘the culture’ is a version of the culture of the 90s, which had reacted to the culture of the 80s by absorbing elements of the culture of the 60s and 70s. And while the artists of 20 or 30 years ago refuse to go away even modern artists from alternative rock to mainstream pop stars make music infused with the sound of 80s synths and 90s rock and so on and on. Nothing wrong with that of course, but what do you call post-post-modernism? And what will the 2020s revival look like when it rears its head in the 2050s, assuming there is a 2050s? Something half interesting, half familiar no doubt.