The 1980s is a decade most often defined – at least in Western countries by some of its most visible features; greed and consumerism, accelerated capitalism, wealth-as-glamour, blockbuster entertainment (and not just in Hollywood; what could be more 80s than the novels of Jackie Collins and Jeffrey Archer?) Even charity – one would think the polar opposite of everything the decade stood for – took on a big, glossy, stadium-filling character. One of the decade’s most beloved humanitarian events, Live Aid was for all its positive impact, complicated at best; essentially an advertisement for the very culture that created gross inequality which simultaneously attempted to right some of its wrongs. If the 70s had been ‘the me decade’ with its post-hippy focus on the discovery and nurturing of the inner self, the 80s turned that focus outwards; now you know who you are it’s time to get what you want – all well and good if you had the means to do it.

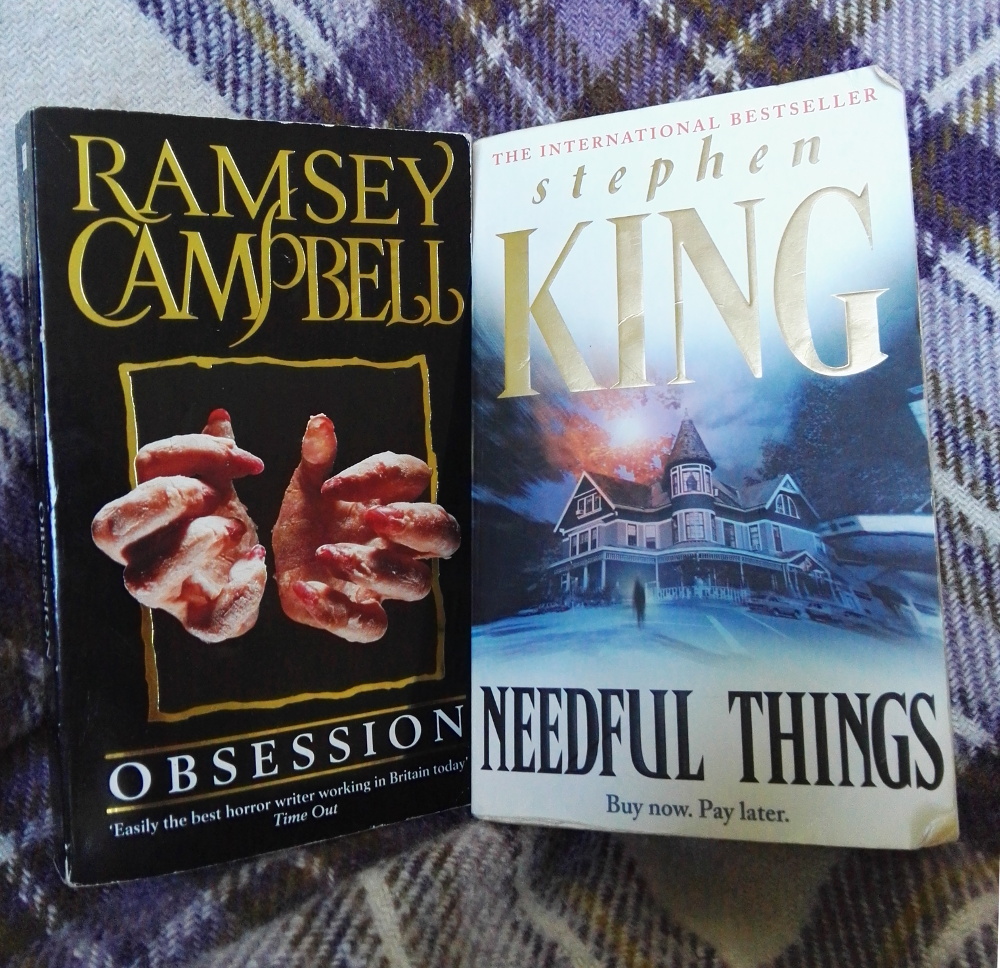

Given that context, it’s no surprise that during that decade, horror authors should have taken on the venerable theme of the Faustian pact; the true cost of getting what you want. The most extreme and morally complex version (that I’ve read) is probably Clive Barker’s The Hellbound Heart (1986; filmed by its author as Hellraiser a few years later), but this article was inspired by a recent reading of two novels: Needful Things by Stephen King (published 1991, but written between 1988-91) and Ramsey Campbell’s Obsession (1985).

The stories are dissimilar but have a kind of 80s horror family likeness; both concern the effect of evil, perhaps supernatural forces in small, ‘sleepy’ communities (Stephen King’s Castle Rock and the seaside town of Seaward in East Anglia) and both depict the lives of their characters unravelling after they are granted their heart’s desire (or at least what they think their heart’s desire is) at a cost which is not apparent until afterwards.

Although more than twice the length of Obsession, Needful Things, in some ways the last of King’s big 80s blockbusters, is the simpler of the two stories. It concerns the arrival in Castle Rock of the sinister Luciferian salesman Leland Gaunt and his shop Needful Things, wherein the town’s residents find objects with apparently great personal value (a signed baseball card, Elvis memorabilia, a fishing rod) at surprisingly affordable prices; but in addition to the cash price, Gaunt also requires his customers to perform duties for him, in the guise of ‘pranks’ which range from the innocuous to the seriously criminal. At the heart of the book are the opposed forces of darkness – Gaunt himself but also the various underlying rivalries and tensions within Castle Rock which he brings to the surface – and if not light, then at least law and order, in the stolid shape of Sheriff Alan Pangborn. Needful Things is a very self-referential novel; King takes for granted that readers will recognise allusions to other ‘Castle Rock’ stories; most obviously The Dark Half (1989) which introduced Pangborn, but also Cujo (1981) and The Body (1982, filmed as Stand By Me), which introduced Leland Gaunt’s petty criminal henchman “Ace” Merrill as a juvenile delinquent teenager. It’s also typical of King’s long (790 pages) novels of the 80s in that it weaves together various plot strands and characters, bringing the story to a dramatic (in fact almost apocalyptic) climax reminiscent of the final, blood-drenched act of the typical 80s horror movie (though the movies themselves were arguably orchestrated in that way because of the influence of King’s earlier works like Carrie (1974).

Sometimes this structure works better than others. For me, it’s at its best in It (1986) where the final catastrophe has an inbuilt logic and even inevitability. The entity terrorising Derry (best known as Pennywise; and really, people think clowns are cool nowadays?? Surely even more lame than finding them scary) pre-dates the city itself and shaped its sinister history. So the destruction of the creature naturally entails the destruction of Derry. It works less well (again, just for me) in Apt Pupil (1982) where the genuinely disturbing opening (one of King’s best) and rising tension is undermined by the ludicrously spiralling body count and in Pet Sematary (1983) where the very human bleakness and nihilism at the novel’s heart is weakened by the over-the-top supernatural carnage of the closing chapters.

Needful Things falls somewhere in the middle; the town being literally blown up at the novel’s climax never feels as necessary or as cathartic as the destruction of Derry in It, but on the other hand, it’s a fitting end to a novel whose main villain is larger-than-life, theatrical and slightly campy and whose hero has a sideline as an amateur magician. If there’s a moral to Needful Things, it’s not only the proverbial ‘be careful what you wish for’ but also a very 80s one; if a deal seems too good to be true, it probably is.

Obsession (Campbell’s preferred and superior title was For The Rest of Their Lives) is less of an extroverted, cinematic rollercoaster ride than Needful Things, but ironically has the blood of a bona fide slick 80s blockbuster – and not a particularly inventive one – running in its veins. The novel’s genesis came when the author was sent to review Rocky III (1982) and became intrigued by the scene in which Apollo Creed agrees to train Rocky with one condition; with the caveat that he won’t find out what that condition is until the training is complete. In Campbell’s story, a troubled teenager in the 1950s receives an anonymous letter offering aid (WHATEVER YOU MOST NEED I DO) with the somewhat vague price of something you do not value and which you may regain. He and four friends take up the offer, with the short term effect that their wishes come true. A quarter century later, the friends are still in Seaward, living outwardly successful lives which proceed to horrifically fall apart.

Stephen King and Ramsey Campbell’s writing styles make for an interesting contrast; as a teenager I found Campbell’s books a little slow and understated for my taste, but in fact one of the most noticeable things about Obsession (which I just read for the first time) is that it feels a little rushed, unfolding over 280 pages where it could comfortably have been twice as long and half as fast-moving. Positively, this brevity makes the story fly by, but it also feels a little disjointed and illogical at times, especially in the final climactic chapters. Where King’s writing is largely conversational in tone (chapter one of Needful Things begins, In a small town, the opening of a new store is big news.* Campbell’s is very carefully-worded and precisely descriptive, although ironically this precision sometimes works against the effect, producing oddly un-illuminating pictures of the people and places involved. In contrast to Needful Things‘s almost cornily old-fashioned opening, Obsession begins Twenty-five years later, when Peter realized at last what they had signed away, he had still not forgotten that afternoon: still remembered the waves flocking down from the horizon to sweep up the fishing boats, the glass of the classroom windows shivering with the wind, chalk dust drowsing in the September sunlight, his throat going dry as he realized everyone was looking at him.** It’s typical of the ambiguous tone of Obsession that after reading what is quite a long descriptive paragraph the reader doesn’t really have a firm idea of the kind of day it was – sunny and windy presumably, but could equally be mellow and warm (chalk dust drowsing) or stormy and cold (waves flocking, windows shivering).

* Needful Things, 1991, New English Library, p.13

** Obsession, 1985, Futura Publications, p.9

Stephen King’s cast of characters is vividly and firmly drawn, a familiar mix of wholesome youngsters gone bad, feuding neighbours, eccentric old timers etc, whereas Campbell’s – at least the four main protagonists – are a little indistinct and interchangeable, not helped by their (entirely plausible but bland) names: Peter Priest, Robin Laurel, Steve Innes and Jimmy Waters. As adults, all four of them lead successful but somewhat tortured existences (Peter is a social worker, Steve an estate agent, Jimmy a police officer and Robin a doctor), all make strange, inconsistent and illogical decisions and can be a little irritating. Where Campbell really excels though is in the antagonists; not larger-than-life supernatural forces of evil like Leland Gaunt, but believable, intensely annoying and depressing people like Robin’s unbearable senile mother and the sinister but ultimately just petty and small-minded brother of one of Peter’s clients.

In keeping with its broad, movie-like feel, Needful Things gives us (relatively) clear dividing lines between good and evil, and shows us the tainting of one by the other, personal gain taking precedence over empathy, but Obsession has no real sense of good and evil at all. None of the main protagonists initially acts out of purely selfish motives, and few of the horrors that happen do so because anybody really means any serious harm. The main characters never seem to fully grasp the bigger picture of what is happening to them or why, and neither, in the end, does the reader. In Needful Things, implausible things happen and the reader, immersed in the story, makes the required suspension of disbelief. In Obsession, whether intended or not, the everyday action – small town dramas involving rival estate agents(!), romantic relationships, sci-fi conventions and drug smuggling – feels as peculiar and implausible as any of the perhaps-supernatural occurrences.

And yet, Obsession is the opposite of unreadable; the dowdy seaside town ambience is irresistible, the almost tangible feeling that the characters are trapped within their own lives, whatever the outcome of the actual plot, makes it both immersive and oddly depressing for an 80s horror novel. Stephen King builds slowly to a frenzied, bloody and cathartic finale where those who commit acts of evil are punished and/or expelled and good, however temporarily, prevails. Ramsey Campbell shows us a world where good and bad are punished equally, peoples’ lives are destroyed, a town is perhaps haunted, but essentially not much of substance ever changes; Stephen King gives us another (efficient and gripping) Hollywood blockbuster, Ramsey Campbell gives us Friday the 13th Part 7 directed by Ken Loach.

What the books share is that they are variations on that cautionary, Faustian tale. The small town settings and down-at-heel characters mean that they aren’t really commentaries on 80s consumerism in the manner of the more imaginative end of horror cinema like David Cronenberg’s surreal Videodrome (1983) and John Carpenter’s satirical They Live (1988). Instead, and appropriately for the Faustian theme, they are concerned with human nature, and as such both books fit into the generally conservative nature of 80s horror (punish the transgressors, restore the status quo!); and although Campbell’s novel is less black and white than King’s, its very ambivalence strengthens that core message; be very careful what you wish for. You can’t always get what you want – and probably, you shouldn’t.