The self-titled debut album by Wreche, a duo consisting of John Steven Morgan (piano/vocals), and Barret Baumgart (drums), released by Fragile Branch Recordings back in May, is undoubtedly one of the most eccentric and striking releases of the year. Almost certainly a love/hate kind of record, this is essentially a black metal album, albeit without most of the musical elements that make up traditional heavy metal (guitars, basically). The band’s name is an Old English word meaning affliction or calamity, deep distress or misery and it’s an appropriately extreme, unsettling and deeply affecting album. In fact, it’s quite unlike anything else I’ve heard and so it seemed like a good idea to ask John, (who, incidentally, also has an excellent non-Wreche album, Solo Piano Works coming out soon) about it – and so…

The most obvious, because most unusual, element in Wreche’s music is your use of the piano. In ‘standard heavy metal’ terms this is a strange and some would say incompatible choice, but somehow it feels absolutely right for the black metal aesthetic, why do you think that is?

“Thank you. We found our skill set and taste fit naturally with black metal. There is so much flexibility compositionally—from long, almost shoe-gaze atmospheric arrangements where the focus is less on individual notes and more on swathes of colour, to abrasive crushing passages and agonised vocals. For us, it was an ideal platform. As for the use of piano, there wasn’t much to decide —it is the instrument that I play and I’ve always played aggressively and texturally. For me, there’s an emotional continuity between metal, jazz, and romantic/modern classical music. I found metal to be the logical extension of the narrative of the piano. Rather than adding classical to metal or playing jazz that quotes metal, we wanted the piano itself to drive the music—it is a heavy instrument on its own (no pun intended) and spans a vast sonic range. It is both string and percussion.”

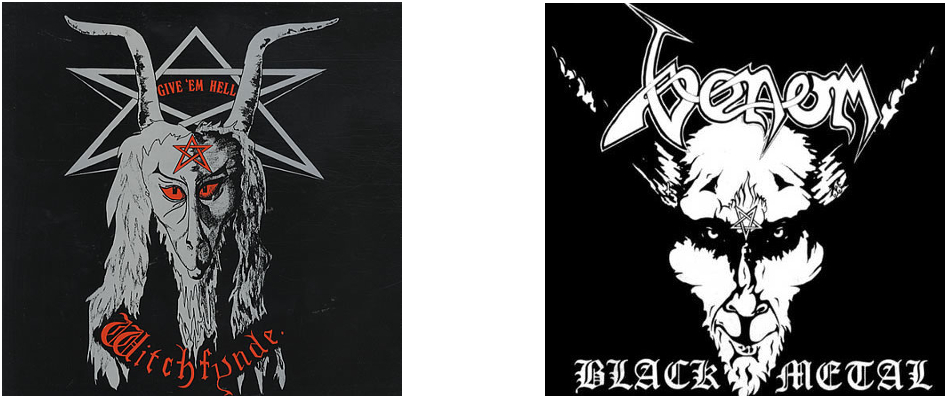

Perhaps a question I should have asked before the last one; do you consider Wreche to be a black metal band?

“Everything has to be called something—it gives a clear reference point for potential listeners. Apart from loving all the great music coming out in the genre (which has definitely inspired us), we felt that metal enthusiasts, specifically “black metal” enthusiasts would be the most receptive to our style and composition. So we call it black metal, but I think there is more to it and it can resonate with those who don’t know anything about black metal. Some of the textural/formal elements conform to the genre, but I see the project as music with some classical, some jazz, and some metal—it is its own thing. The tough part about picking a genre is that we now deal with the “novelty” aspect which can be good if the music transcends it, but bad if nobody considers it apart from the black metal foundation.”

Obviously, as the composers of your music you are in control of it, but would you say it’s a tool for expressing what you want to express, or do you find that the act of making music itself takes you in directions you hadn’t necessarily considered?

“A little bit of both. With the first, I think expressing an emotion through your instrument is a gradual process. I can feel a certain way, but it won’t necessarily translate into piano music that day. The compositions took months so there were spurts of turmoil, ecstasy, violence and isolation where I could write passages same-day for days at a time locked in the studio. On the other hand, some emotions had to settle in and eventually work their way out. As for the latter case, the act of making music influencing the compositions themselves, that also played a part. I write from the keyboard, so errors or occasional stand-out phrases in practicing one thing led to new parts. I am always open to the focal point of a passage changing emphasis if it leads to more effective, evocative music.”

Compared to other forms of metal, black metal has often been involved with spiritual, metaphysical or philosophical concerns, rather than purely earthly ones, with the forms of the music acting almost as a catalyst/lightning rod for the energies that bands are channelling; is the music a tool in this way for Wreche?

“In a way it is, however I don’t live in the forest, outer space, or subscribe to religion. I do look at the stars and feel awe, weightless existential ecstasy, and sadness. But, I think the music comes from earth. I grew up in the desert, but for the last 13 years I’ve been traversing and staring at city blocks. I play music in the street for a living and have always only been able to afford housing in blighted neighbourhoods. The spiritual or philosophical drive, if you can call it that, comes from my observations of the human condition and metaphorical “desert” in the cities we exist – especially in Los Angeles. There are so many broken people, crammed to capacity on freeways, office buildings, sidewalks, who are barely staying afloat or are lost altogether. They are in a chokehold – always needing money, never having enough of it, and never able to catch a breath. All the while we have a steadily rising wealth inequality, a dying earth, and booming technology designed to express our individuality and our successes. The misery, anxiety, irony and sadness of it all is overwhelming. In this way, I think the music confronts and reflects.”

The album has a very intense, pervasive haunted quality, is that something that you felt while making it?

“Definitely. Besides the actual tone I managed to get out of the piano, this album partially reflects on my own life, personal growth and the repurposing of my playing style. Whether through piano lines, lyrics, song titles or samples, the music is peppered with snapshots and memories from the past. Another factor was probably that I spent almost a straight year living out of the rehearsal studio during this time. It was extremely isolating, money was tight, and I was in a new environment having just left my previous band in Oakland to work on this album. Some nights were real bad, and the city has that effect on people—high anxiety, sleepless nights, anonymity. I felt invisible roaming the streets or looking out the window, always in my head, like I was dead already. A real ghoul.

Barret also had recently completed a book basically about climate change, geoengineering, and human extinction—I know he brought that cheerful perspective to some of the writing as well.”

Do you find the surroundings of a recording studio a conducive environment for making this kind of music? Does the environment affect the feeling you capture when recording?

“I really do. Some people can write anywhere, but I like feng-shui. Our studio, by pure chance, has a wall of windows that overlook the Los Angeles river and a view of the complete LA skyline. It was beautiful at times and oppressive or sinister at others. We opted to record the album ourselves so that there would be no time limit or stress about how much money a formal studio costs per hour. In this way, I was able to make decisions at a pace that allowed the music to develop over several drafts.”

Your album feels like a strangely intimate kind of black metal chamber music, which could translate very well to extremely atmospheric live shows, is playing live something that interests you?

“I think the music, while abrasive, is really something that works well played loud and alone—maybe in the dark. We would love to play live shows, but so far, our focus was to make the best music we could with our respective instruments. Now that we have finished the first album, I’m anxious and excited about getting back to writing and trying new things. However, if the opportunity arises to travel and play, I’ve been working on several ideas for that. I would like to involve Max [Moriyama] and Athena [Witosky]’s artwork in an impactful way, and if possible, some of the Wreche film Zack Kasten is creating for the project.”

Unlike the majority of new black metal releases, where the listener can easily pinpoint key influences, Wreche have a sound that is completely unfamiliar in the metal genre, are your musical influences mainly from the black metal world or beyond?

“I love black metal and the greater genre of metal, but my background and taste started with Pink Floyd as a teen. I delved heavily into classical and jazz too—which I think set me up nicely for metal. I would say apart from Pink Floyd, huge influences on me musically are Hella, Ethan Iverson of the Bad Plus, Jackie Mclean, Thelonious Monk, Eric Dolphy, Chopin, Shostokovich, Beethoven, Scriabin, and Rachmaninov. Recently in metal, we both look to Ulcerate and Krallice. Lately, I’ve really been enjoying Ultha’s Pain Cleanses Every Doubt and this CD I have in my van of Sviatoslav Richter playing Scriabin Etudes and Poemes. Richter is the master.”

Do you see Wreche as a band with a specific overarching concept/philosophy, or can it tackle any direction/theme you have in mind at any given time?

“I think Wreche is, by design, an open platform. It isn’t based on a particular philosophy, just a reflection of the human condition filtered through our perception. Black metal is a great starting platform, as I’ve said, but I can see a lot of potential with these two instruments, the potential even for evolution outside of the genre. The focus will always be on writing the best possible music—to push our limitations, with all other styles and textures as tools.”

Many thanks to John for the interview! Check out Wreche on Facebook

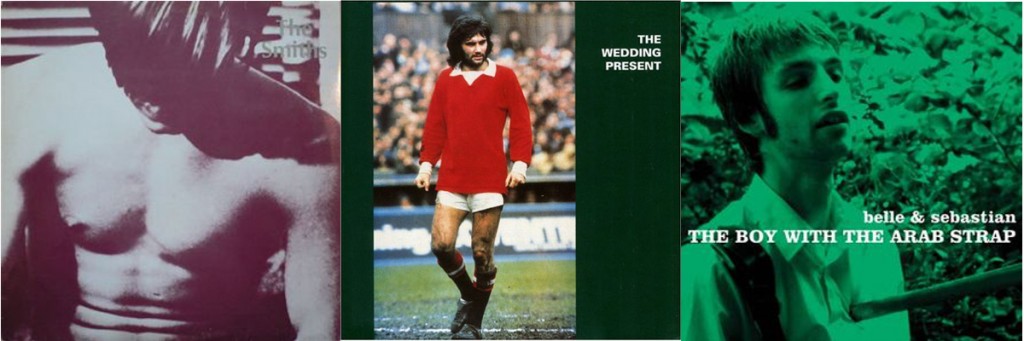

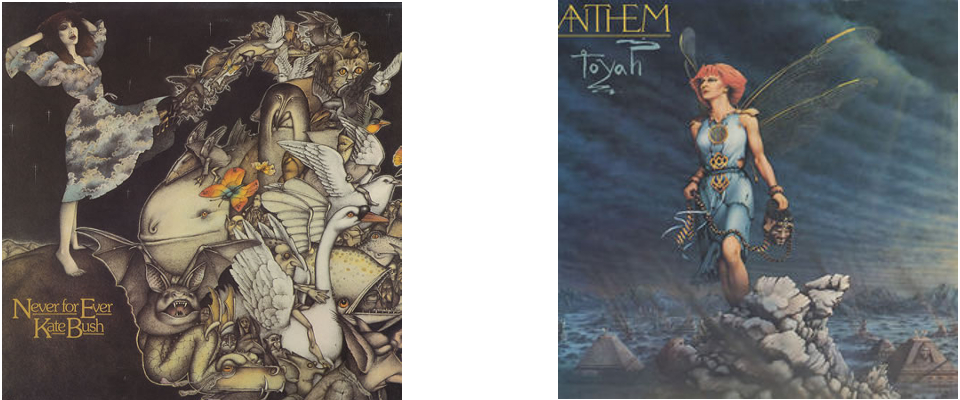

But what did I hear first? Who knows? I remember my mother playing guitar and singing, but ridiculously, the actual song that stands out as the first identifiable thing I remember, can name and even know some of the words to is neither parent music, nor standard chart fare; it’s Day Trip To Bangor by Fiddler’s Dram, which sets the date I began to really absorb music at around 1979; which makes sense, as until around that point I had hearing problems. As earliest memories go it could be more significant – I didn’t like it (or dislike it, as far as I remember), I can’t picture the band, it isn’t the soundtrack to a specific event. I just remember it, like I remember Crown Court and Pebble Mill At One being on TV in the afternoon if I was ill at home instead of being at school. It’s also to the end of the 70s that the first 7” single actually owned by me belongs and it’s also a typical-of-its-era novelty record, by the already long-in-the-tooth comedy group The Barron Knights – ‘A Taste of Aggro’. It’s the kind of random thing that little kids like; it features parodies of ‘The Smurf Song’ and Boney M’s ‘Rivers of Babylon’ (‘there’s a dentist in Birmingham…’ ). In my first year or two at primary school I also remember liking at least one Adam and the Ants song, I liked Toyah and Hazel O’Connor when they were on TV, I liked the disco version of the Star Wars theme and ‘Cars’ by Gary Numan. Other music-related memories of the time are pretty vague; I remember older kids who were punks and (more scary to small-child me) skinheads, but I don’t think I ever heard their music at the time.

But what did I hear first? Who knows? I remember my mother playing guitar and singing, but ridiculously, the actual song that stands out as the first identifiable thing I remember, can name and even know some of the words to is neither parent music, nor standard chart fare; it’s Day Trip To Bangor by Fiddler’s Dram, which sets the date I began to really absorb music at around 1979; which makes sense, as until around that point I had hearing problems. As earliest memories go it could be more significant – I didn’t like it (or dislike it, as far as I remember), I can’t picture the band, it isn’t the soundtrack to a specific event. I just remember it, like I remember Crown Court and Pebble Mill At One being on TV in the afternoon if I was ill at home instead of being at school. It’s also to the end of the 70s that the first 7” single actually owned by me belongs and it’s also a typical-of-its-era novelty record, by the already long-in-the-tooth comedy group The Barron Knights – ‘A Taste of Aggro’. It’s the kind of random thing that little kids like; it features parodies of ‘The Smurf Song’ and Boney M’s ‘Rivers of Babylon’ (‘there’s a dentist in Birmingham…’ ). In my first year or two at primary school I also remember liking at least one Adam and the Ants song, I liked Toyah and Hazel O’Connor when they were on TV, I liked the disco version of the Star Wars theme and ‘Cars’ by Gary Numan. Other music-related memories of the time are pretty vague; I remember older kids who were punks and (more scary to small-child me) skinheads, but I don’t think I ever heard their music at the time.

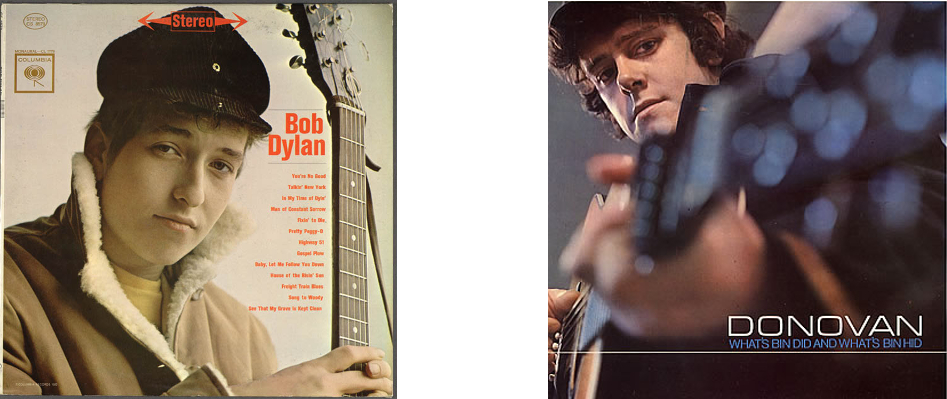

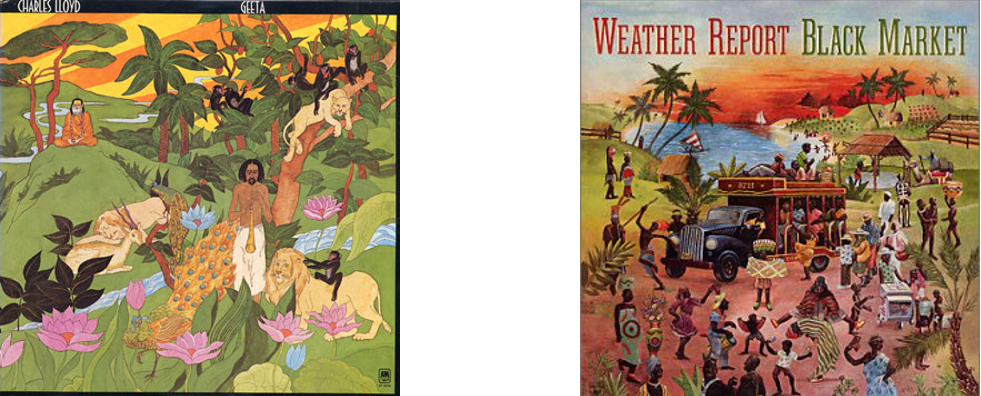

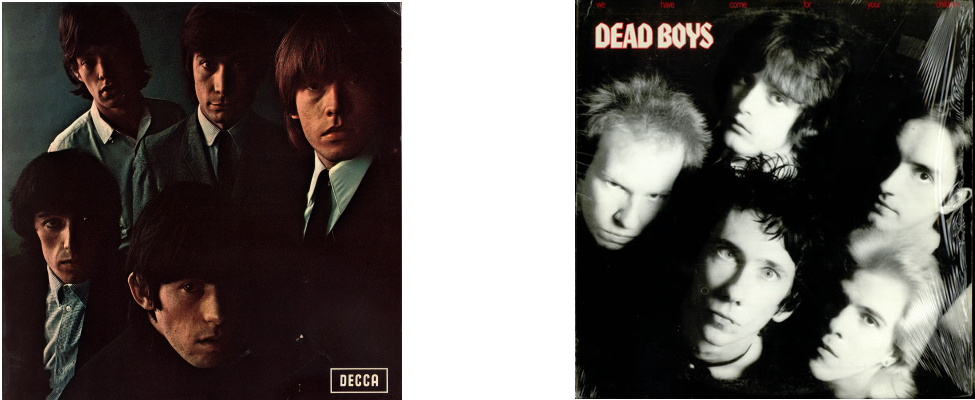

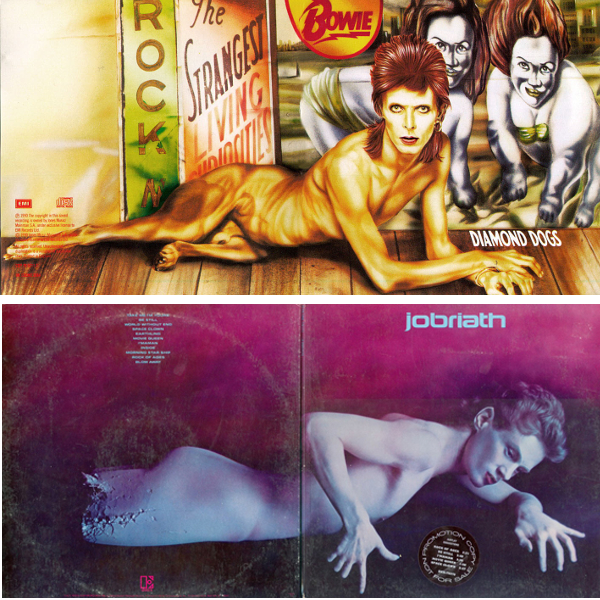

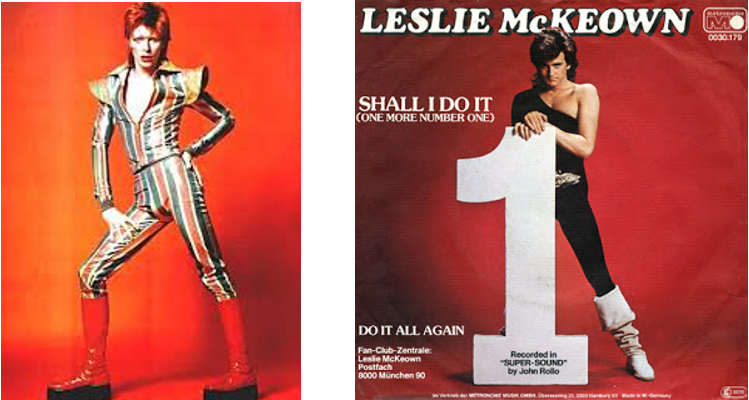

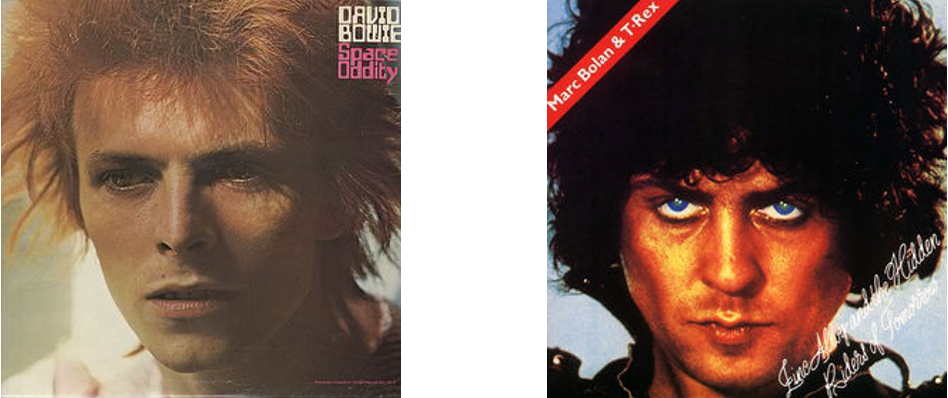

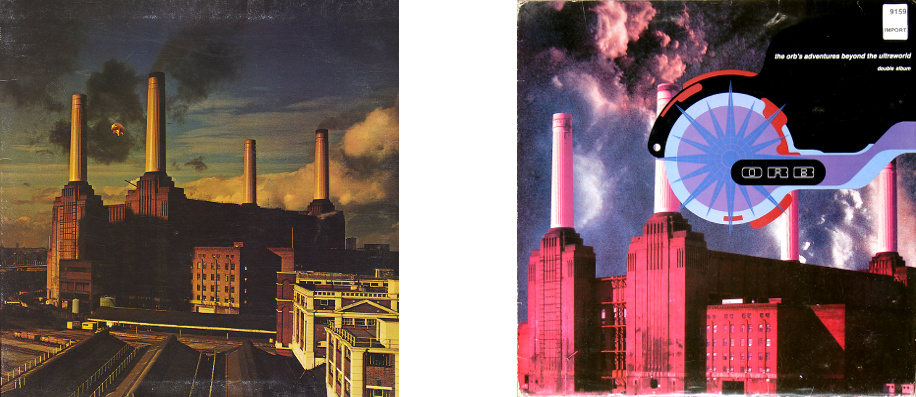

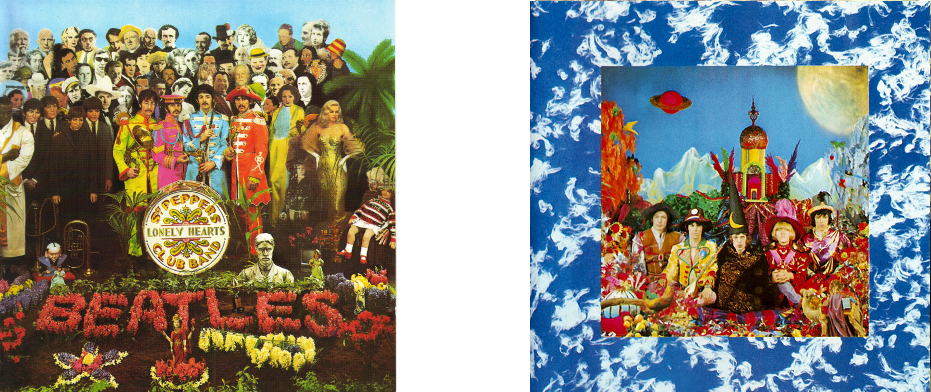

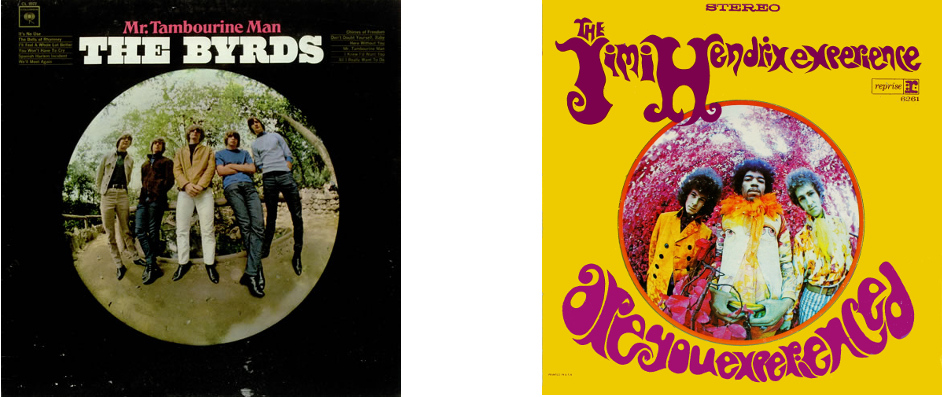

This comparison really traces the advance of psychedelia from a mild distortion of perception to a neon-coloured hallucination over the two years 1965-67

This comparison really traces the advance of psychedelia from a mild distortion of perception to a neon-coloured hallucination over the two years 1965-67