In the 2020s, the Police may feel beleaguered by the pressure to account for their actions and act within the boundaries of the laws that they are supposed to be upholding, but despite the usual complaints from conservative nostalgists about declining standards of respect, the question of ‘who watches the watchmen’ (or, ‘who will guard the guards’ or however Quis custodiet ipsos custodies? is best translated) is hardly new, and probably wasn’t new even when that line appeared in Juvenal’s Satires in the 2nd century AD.

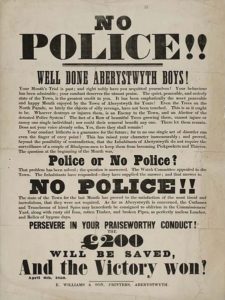

In the UK (since I’m here), the modern police force (and quasi-police forces like the Bow Street Runners) have almost always been controversial from their foundations in the 18th century onwards – and not surprisingly so.

It’s probably true that the majority of people have always wanted to live their lives in peace, but ‘law and order’ is not the same thing as peace. The ‘order’ comes from the enforcement of the law, and ‘the law’ has never been a democratically agreed set of rules. So law and order is always somebody’s law and order, but not everybody’s. As is often pointed out, most of the things which we currently regard as barbaric in the 21st century, from slavery and torture to child labour and the lack of universal suffrage, were all technically legal. ‘Respect for the law’ may not just be a different thing from respect for your fellow human beings, it might be (and often has been) the opposite of it; so it’s no wonder that the position of the gatekeepers of the law should often be ambiguous at best.

It’s probably true that the majority of people have always wanted to live their lives in peace, but ‘law and order’ is not the same thing as peace. The ‘order’ comes from the enforcement of the law, and ‘the law’ has never been a democratically agreed set of rules. So law and order is always somebody’s law and order, but not everybody’s. As is often pointed out, most of the things which we currently regard as barbaric in the 21st century, from slavery and torture to child labour and the lack of universal suffrage, were all technically legal. ‘Respect for the law’ may not just be a different thing from respect for your fellow human beings, it might be (and often has been) the opposite of it; so it’s no wonder that the position of the gatekeepers of the law should often be ambiguous at best.

Popular culture, as it tends to do – whether consciously or not – reflects this uneasy situation. Since the advent of film and television, themes of law enforcement and policing have been at the centre of the some of mediums’ key genres, but the venerable Dixon of Dock Green notwithstanding, the focus is only very rarely on orthodox police officers faithfully following the rules. Drama almost invariably favours the maverick individualist who ‘gets the job done’* over the methodical, ‘by the book’ police officer, who usually becomes a comic foil or worse. And from the Keystone Cops (or sometimes Keystone Kops) in 1912 to the present day, the police in comedies are almost invariably either inept or crooked (or both; but more of that later).

*typically, the writers of Alan Partridge manage to encapsulate this kind of stereotype while also acknowledging the ambiguity of its appeal to a conservatively-minded public. Partridge pitches ‘A detective series based in Norwich called “Swallow“. Swallow is a detective who tackles vandalism. Bit of a maverick, not afraid to break the law if he thinks it’s necessary. He’s not a criminal, you know, but he will, perhaps, travel 80mph on the motorway if, for example, he wants to get somewhere quickly.’ i.e. he is in fact a criminal, but one that fits in with the Partridgean world view

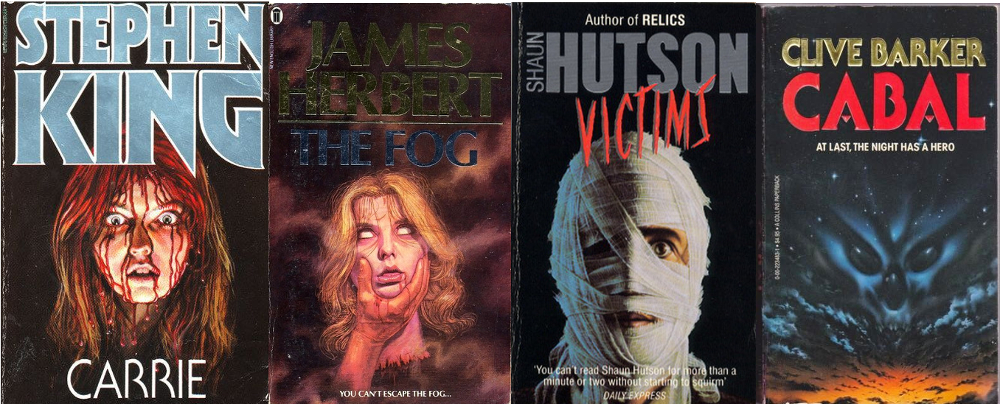

But perhaps the police of the 2020s should think themselves lucky; they are currently enduring one of their periodic crisis points with public opinion, but they aren’t yet (again) a general laughing stock; perhaps because it’s too dangerous for their opponents to laugh at them, for now. But almost everyone used to do it. For the generations growing up in the 70s and 80s, whatever their private views, the actual police force as depicted by mainstream (that is, mostly American) popular culture was almost exclusively either comical or the bad guys, or both.

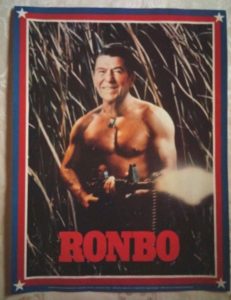

The idiot/yokel/corrupt/redneck cop has an interesting cinematic bloodline, coming into their own in the 1960s with ambivalent exploitation films like The Wild Angels (1966) and genuine Vietnam-war-era countercultural artefacts like Easy Rider, but modulating into the mainstream – and the mainstream of kids’ entertainment at that – with the emergence of Roger Moore’s more comedic James Bond in Live and Let Die in 1973. This seems to have tonally influenced similar movies like The Moonrunners (1975; which itself gave birth to the iconic TV show The Dukes of Hazzard, 1979-85), Smokey and the Bandit (1977), Any Which Way You Can (1980) and The Cannonball Run (1981) among others. Variations of these characters – police officers concerned more with the relentless pursuit of personal vendettas than actual law enforcement, appeared (sometimes sans the redneck accoutrements) in both dramas (Convoy, 1978) and comedies (The Blues Brothers, 1980), while the more sinister, corrupt but not necessarily inept police that pushed John Rambo to breaking point in First Blood (1982) could also be spotted harassing (equally, if differently, dysfunctional Vietnam vets) The A-Team from 1983 to ’85.

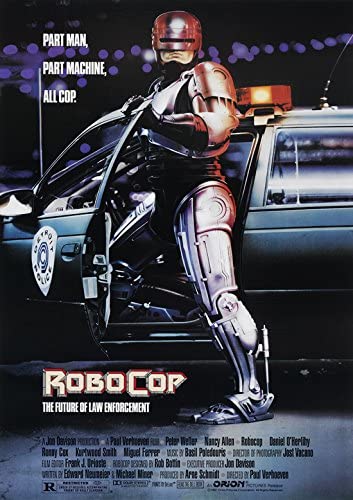

In fact, the whole culture of the police force was so obviously beyond redemption as far as the makers of kids and teens entertainment were concerned, that the only cops who could be the good guys were the aforementioned ‘mavericks.’ These were borderline vigilantes who bent or broke or ignored the rules as they saw fit, but who were inevitably guided by a rigid sense of justice that was generally unappreciated by their superiors. This kind of cop reaches some kind of peak in Paul Verhoeven’s masterly Robocop (1987). Here, just beneath the surface of straightforward fun sci-fi/action movie violent entertainment, the director examines serious questions of ‘law’ vs ‘justice’ and the role of human judgement and morality in negotiating between those two hopefully-related things. Robocop himself is, as the tagline says ‘part man, part machine; all cop’ but the movie also gives us pure machine-cop in the comical/horrific ED-209, which removes the pesky human element that makes everything so complicated and gives us instead an amoral killing machine. The film also gives us good and bad human-cops, in the persons of Officer Lewis and Dick Jones. Lewis (the always-great Nancy Allen) has a sense of justice is no less keen than that of her robot counterpart, but her power is limited by the machinations of the corrupt hierarchy of the organisation she works for, and she’s vulnerable to physical injury. Jones (the brilliant Ronny Cox) is very aware of both the practical and moral problems with law enforcement, but he’s than happy to benefit personally from them.

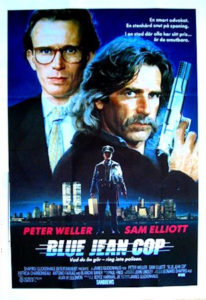

The following year, Peter Weller (Robocop himself) returned in the vastly inferior Shakedown, worthy of mention because it too features unorthodox/mismatched law enforcers (a classic 80s trope, here it’s Weller’s clean-cut lawyer and Sam Elliott’s scruffy, long haired cop) teaming up to combat a corrupt police force; indeed the movie’s original tagline was Whatever you do… don’t call the cops. And it’s also worthy of mention because its UK (and other territories) title was Blue Jean Cop, though it sadly lacked the ‘part man, part blue jean; all cop’ tagline one would have hoped for). Into the 90s, this kind of thing seemed hopelessly unsophisticated, but even a ‘crooked cops’ masterpiece like James Mangold’s Cop Land (1997) relies, like Robocop, on the police – this time in the only mildly unconventional form of a good, simple-minded cop (Sylvester Stallone), to police the bad, corrupt, too-clever police, enforcing the rules that they have broken so cavalierly. The film even ends with the explicit statement (via a voiceover) that crime doesn’t pay; despite just showing the viewer that if you are the police, it mostly seems to, for years, unless someone else on the inside doesn’t like it.

There’s always an ironic focus on ‘the rules’ – ironic because the TV and movie police tend to be bending them a-la Starsky and Hutch (and the rest), or ineffectually wringing their hands over that rule-bending, like the strait-laced half of almost every mismatched partnership (classic examples being Judge Reinhold in 1984’s Beverley Hills Cop and Danny Glover in Lethal Weapon, another famous ‘unorthodox cop’ movie from the same year as Robocop) or even disregarding them altogether like Clint Eastwood’s Dirty Harry. So, it’s no surprise that the training of the police and the learning of those rules should become the focus of at least one story. Which brings us to Police Academy.

Obviously any serious claim one makes for Police Academy is a claim too far. It’s not, nor was it supposed to be, a serious film, or even possibly a good film, and certainly not one with much of a serious message. But its theme is a time-honoured one; going back to the medieval Feast of Fools and even further to the Roman festival of Saturnalia, it’s the world upside down, the lords of Misrule. And in honouring this tradition, the film tells us a lot about the age that spawned it. Police Academy purports to represent the opposite of what was the approved behaviour of the police in 1984 and yet, despite its (not entirely unfounded) reputation for sexism and crass stereotypes it remains largely watchable where many similar films do not. But, more surprisingly, it also feels significantly less reactionary than, say the previous year’s Dirty Harry opus, Sudden Impact.

While it’s a trivial piece of fluff, Police Academy is notable for – unlike many more enlightened films before and since – passing the Bechdel test. Don’t expect anything too deep – not just from the female characters – but it also has having noticeably more diversity among its ensemble cast than the Caddyshack/National Lampoon type of films that were in its comedy DNA. Three prominent African-American characters with more than cameo roles in a mainstream Hollywood movie may not seem like much – and it definitely isn’t – but looking at the era it feels almost radical. At this point in Hollywood history, let’s not forget, the idea for a film where a rich white kid finds the easiest way to get into college is by disguising as a black kid not only got picked up by a major studio, but actually made it to the screen.

In that context, these three actors – Marion Ramsey, Michael Winslow and the late Bubba Smith could look back on a series of movies which may not have been* cinematic masterpieces, but which allowed them to use their formidable comedic talents in a non-token way. More to the point, their race is neither overlooked in a ‘colourblind’ way (they are definitely Black characters rather than just Black actors playing indeterminate characters) or portrayed in a negative sense. Police Academy is not an enlightened franchise by any means; the whole series essentially runs on stereotypes and bad taste and therefore has the capacity to offend pretty much everyone. But although there are almost certainly racial slurs to be found there, alongside (for sure) gross sexism, homophobia etc, the series is so determined to make fun of every possible point of view that it ends up leaving a far less bad smell behind it than many of its peers did; perhaps most of all the previously alluded to Soul Man (1986).

*ie they definitely aren’t

Despite its essential good nature though, there is a genuine, if mild kind of subversion to be found in the Police Academy films. With the Dickensian, broadly-drawn characters comes a mildly rebellious agenda (laughing at authority), but it also subverts in a more subtle (and therefore unintentional? who knows) way, the established pattern of how the police were depicted. Yes, they are a gang, and as such they are stupid and corrupt and vicious and inept, just like the police of Easy Rider, Smokey and the Bandit, The Dukes of Hazzard etc. Unlike all of those films and franchises though, Police Academy offers a simple solution in line with its dorky, good natured approach; if you don’t want the police to suck, it implies, what you need to do is to recruit people who are not ‘police material.’ In the 1980s those who were not considered traditional ‘police material’ seemingly included ethnic minorities, women, smartasses, nerds, and at least one dangerous gun-worshipper, albeit one with a sense of right and wrong that was less morally dubious than Dirty Harry’s. So ultimately, like its spiritual ancestors, Saturnalia and the Feast of Fools, Police Academy is more like a safety valve that ensures the survival of the status quo rather than a wrecking ball that ushers in a new society. Indeed, as with Dickens and his poorhouses and brutal mill owners, the message is not – as you might justifiably expect it to be – ‘we need urgent reform’, but instead ‘people should be nicer’. It’s hard to argue with, as far as it goes, but as always seems to be the case*, the police get off lightly in the end.

*one brutal exception to this rule is roughly the UK equivalent of Police Academy, the risible 1982 Cannon & Ball vehicle The Boys In Blue. After sitting through an impossibly long hour and a half of Tommy and Bobby, the average viewer will want not only to dismantle the police force, but also set fire to the entire western culture that produced it.