Remembering 1984 as someone who was a child then, I find that although the clocks didn’t strike thirteen as in the novel, the year – as encapsulated by two specific and very different but not unconnected childhood memories, as we’ll see – is almost as alien nowadays as Orwell’s Airstrip One. Of course, I know far more now about both 1984 and Nineteen Eighty-Four than I did at the time, but I was aware – thanks mostly I think to John Craven’s Newsround – of the big, defining events of the year.

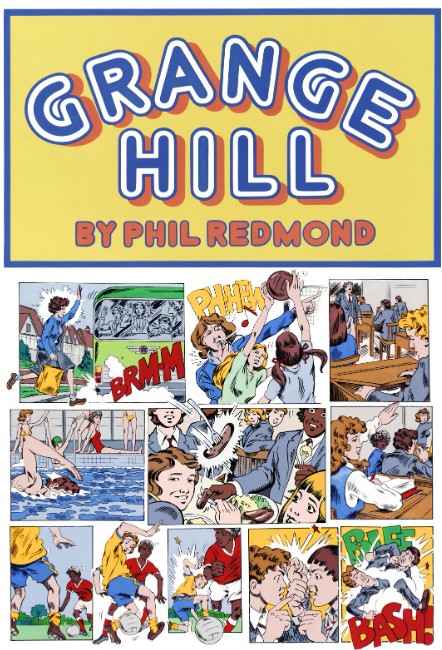

I knew, for instance about the Miners’ Strike and the Greenham Common Women’s Peace Camp, but they didn’t have anything like the same impact on me personally as Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. I remember Zola Budd tripping or whatever it was at the Olympics and Prince Harry being born, but they weren’t as important to me as Strontium Dog or Judge Dredd. Even Two Tribes by Frankie Goes to Hollywood made a bigger impression on me than most of the big news events of the year, despite the fact that I didn’t like it. My favourite TV show that year was probably Grange Hill – and here we go.

Grange Hill – essentially a kids’ soap opera set in a big comprehensive high school in London – ran for 30 years and I recently discovered that the era of it that I remember most fondly – the series’ that ran from 1983-6 – is available on YouTube. When I eventually went to high school later in the 80s, my first impression of the school was that it was just like Grange Hill, and now I find that despite the silliness and melodrama, Grange Hill still reflects the reality, the look and the texture of my high school experience in the 80s with surprising accuracy.

But anyway, watching old Grange Hill episodes out of nostalgia, I was struck by how good it seems in the context of the 2020s, despite the obvious shortcomings of being made for children. Check out this scene from series seven, episode five, written by Margaret Simpson and which aired in January of 1984. Among typical story arcs about headlice and bullying, the Fifth form class (17 year olds getting towards the end of their time at school) get the opportunity to attend a mock UN conference with representatives from other schools. In a discussion about that, the following exchange occurs between Mr McGuffy (Fraser Cains) and his pupils Suzanne Ross (Susan Tully), Christopher “Stewpot” Stewart (Mark Burdis), Claire Scott (Paula-Ann Bland) and Glenroy (seemingly of no last name) (Steven Woodcock). It’s worth noting that this was the year before Live Aid.

Suzanne: [re. the UN]:"It's about as effective as the school council." Mr McGuffy: "Oh well I wouldn't quite say that. The UN does some excellent work - UNESCO, the Food and Agriculture Organisation, the UN Peacekeeping force..." [...] Claire: "What's the conference gonna be about?" Mr McGuffy: "The world food problem. There was a real UN conference on this topic ten years ago..” Glenroy: "Didn't solve much then, did they? Millions of people still starvin'" Stewpot: ”Yeah that's cos they ain't got no political clout to do anything about it though, ain't it" Glenroy: ”Naw man, it's because the rich countries keep them that way” Suzanne: “The only chance a poor country's got is if it's got something we want” Glenroy: “That's right - they got something the West wants and they'd better watch out because the West starts to mess with their government." Mr McGuffy: "Well it's clear from what you've all said so far that you're interested in the sort of issues that will be discussed that weekend..."

It’s not an exaggeration to say that that is a more mature political discussion than is often heard on Question Time in 2025. Interestingly, it’s not an argument between left and right as such, but between standard, humanitarian and more radical left-wing viewpoints. Needless to say, if it was presented on a TV show that’s popular with ten year-olds nowadays, a certain demographic would be foaming at the mouth about the BBC indoctrinating the young with “wokeness.” But as a kid this sort of discussion didn’t at all mar my enjoyment of the show, Naturally there’s also a lot of comedic stuff in the series about stink bombs and money-making schemes, but one of the reasons that Grange Hill remained popular (and watchable for 8 year-olds and 15 year-olds alike) for so many years was that it refused to talk down to its audience.

The way the writers tackled the obvious big themes – racism, sexism, parents getting divorced, bullying, gangs, sex education etc – are impressive despite being quite broad, especially when the younger pupils are the focus of the storyline, but what makes a bigger impression on me now is the background to it all. It’s a little sad – though true to Thatcher’s Britain – to see through all this period the older pupils’ low-level fretting about unemployment and whether it’s worth being in school at all.

And maybe they were right. In 1984, when Suzanne and Stewpot were 17, a fellow Londoner who could, in a parallel universe, have been in the year above them at Grange Hill was the 18-year-old model Samantha Fox. That year, she was The Sun newspaper’s “Page 3 Girl of the Year.” She had debuted as a topless model for the paper aged 16, which is far more mind-boggling to a nostalgic middle-aged viewer of Grange Hill than it would have been to me at the time. Presumably, some parts of the anti-woke lobby would not mind Sam’s modelling as much as they would mind the Grange Hill kids’ political awareness, but who knows?

Naturally, the intended audience for Page 3 wasn’t Primary School children – but everybody knew who Sam Fox was and in the pre-internet, 4-channel TV world of 80s Britain, she had a level of fame far beyond that of any porn star 40 years later (arguments about whether or not Page 3 was porn are brain-numbingly stupid, so I won’t go there; and anyway, I don’t use porn as a derogatory term).

Whatever; Sam (she’ll always be “Sam” to people who grew up in the 80s) and her Page 3 peers made occasional accidental appearances in the classroom, to general hilarity, when the class was spreading old newspapers on our desks to prepare for art classes. It was also pretty standard then to see the “Page Three Stunnas” (as I think The Sun put it) blowing around the playground or covering a fish supper. It was nothing like growing up with the internet, but in its own way the 80s was an era of gratuitous nudity.

Meanwhile, on Page Three of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith – who is, shockingly, a few years younger than I am now – is trying to look back on his own childhood to discern whether things were always as they are now:

“But it was no use, he could not remember: nothing remained of his childhood except a series of bright-lit tableaux, occurring against no background and mostly unintelligible.” George Orwell, Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949) P.3 – New Windmill edition, 1990

By contrast, some of the roots of 2025 are plain to see in 1984, despite the revolution of the internet that happened halfway between then and now. As the opposing poles of the Grange Hill kids and The Sun demonstrate, there were already tensions in British society which would never so far be resolved, but they would come to some kind of semi-conclusion at the end of the Thatcher era when when ‘Political Correctness,’ the chimerical predecessor of the equally chimerical ‘Woke’ began to work in its unpredictable (but I think mostly positive) ways.

Most obviously, Page 3 became ever more controversial and was toned down (no nipples) and then vanished from the tabloids altogether for a while (though in the 90s the appearance of “lads’ mags” which mainstreamed soft porn made the death of Page 3 kind of a pyrrhic victory.) More complicatedly, the kind of confrontational storylines about topics like racism that happened in kids shows in the 80s became a little more squeamish, to the point where (for entirely understandable reasons) racist bullies on kids’ shows would rarely use actual racist language and then barely appear at all, replaced by positivity in the shape of more inclusive casting and writing. Nice and I think genuinely positive in a way, but it began to look pretty quaint quite quickly as soon as the internet with its love of edgy polarisation and tolerance of any kind of extremism really took off.

So, that was part of the 1984 that I remember; what Orwell would have made of any of it I don’t know. It wasn’t his nineteen eighty-four, which might have pleased him. For me, it all looks kind of extreme and problematic, but also refreshingly straightforward, though I’m sure I only think so because I was a child then and lived through it unscathed. It’s all very Gen-X isn’t it?

Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so.

Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so. Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears.

Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears. every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation

every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation  isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism.

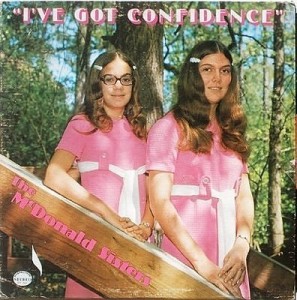

isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism. Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all.

Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all. This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.

This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.