There are two kinds of people* – those who like forewords, introductions, prefaces, author’s notes, footnotes, appendices, bibliographies, notes on the text, maps, diagrams etc, and those who don’t. But we’ll get back to that shortly.

* there are more than two kinds of people. Possibly infinite kinds of people. Or maybe there’s only one kind; I’m never sure

A few times recently, I’ve come across the idea (which I think is mainly an American academic one, but I might be completely mistaken about that) that parentheses should only be used when you really have to use them (but when do you really have to?) because anything that is surplus to the requirements of the main thrust of one’s text is surplus to requirements full stop, and should be left out. But that’s wrong. That criticism can be and is extended to anything that interrupts the flow* of the writing. But that is also wrong.

*like this¹

Unless you happen to be writing a manual or a set of directions or instructions, writing isn’t (or needn’t be) a purely utilitarian pursuit and the joy of reading (and of writing) isn’t in how quickly or ‘efficiently’ (whatever that means in this context) you can do it. Aside from technical writing, the obvious example where economy just may be valuable is poetry – which however is different and should probably have been included in a footnote, because footnotes are useful for interrupting¹ and expanding on text without separating the point you’re making from the point you’re commenting on or adding to.

¹but bear in mind that if the interrupting is deliberate – people don’t write footnotes by accident – then it’s not a negative thing²

²and it can sometimes be funny

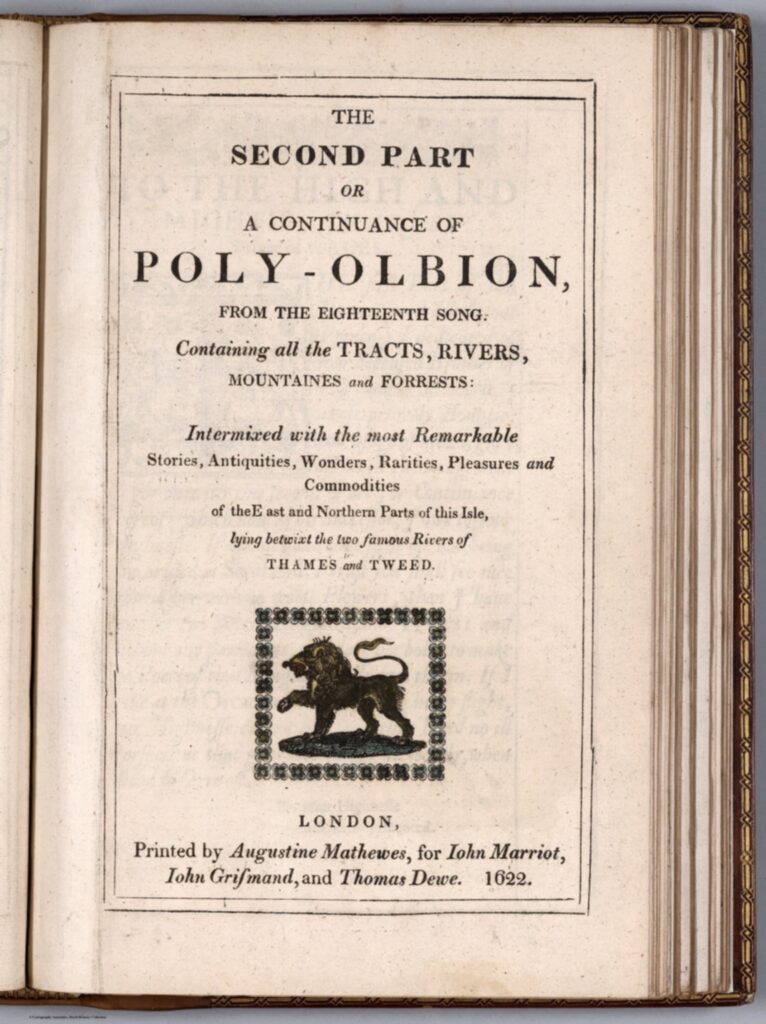

I would argue (though the evidence of poetry itself – especially the kind of expansive, long-winded poetry that I’m quite fond of, like Paradise Lost, Spenser’s Faerie Queen and Michael Drayton’s Poly-Olbion or even Craig Raine’s History – the Home Movie – perhaps argues against me) that a poem should be* the most economical or at least the most effective way of saying whatever you have to say. But even as I write that, it seems obvious that economical and effective are not necessarily the same thing. Some things can be expeessed in a few words, others can’t

* poets, ignore this; there is no should be in poetry

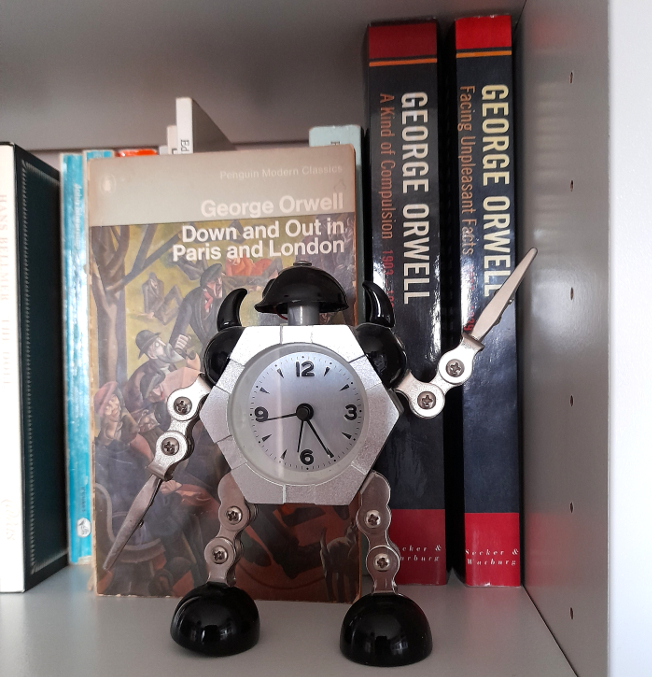

Clearly (yep), the above is a needlessly convoluted way of writing, and can be soul-achingly annoying to read; but – not that this is an effective defence – I do at least do it on purpose. As anyone who’s read much here before will know, George Orwell is one of my all-time favourite writers, and people love to quote his six rules for writing, but while I would certainly follow them if writing a news story or article where brevity is crucial, otherwise I think it’s more sensible to pick and choose. So, Orwell says;

Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print. Absolutely; although sometimes you use them because they are familiar, if making a specific point, or being amusing. Most people, myself included, just do it by accident; because where does the dividing line fall? In this paragraph I have used “by accident” and “dividing line” which seem close to being commonly used figures of speech (but then so does “figure of speech”). But would “accidentally” or something like “do it without thinking” be better than “by accident?” Maybe.

Never use a long word where a short one will do. The key point here is will do. In any instance where a writer uses (for example) the word “miniscule” then “small” or “tiny” would probably “do”. But depending on what it is they are writing about, miniscule or microscopic might “do” even better. Go with the best word, not the shortest, unless it’s also the best.

If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out. Note that Orwell wrote ‘always’ here where he could just have said If it is possible to cut a word out, cut it out. Not everything is a haiku, George.

Never use the passive where you can use the active. Surely it depends what you’re writing? If you are trying, for instance, to pass the blame for an assault from a criminal on to their victim, you might want a headline that says “X stabbed after drug and alcohol binge” rather than “Y attacks X.” You kind of see Orwell’s point though.

Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent. Both agree and disagree; as a mostly monolingual person I agree, but some words and phrases (ironically, usually ones in French, a language I have never learned and feel uncomfortable trying to pronounce; raison d’etre or enfant terrible for example) just say things more quickly and easily (I can be utilitarian too) than having to really consider and take the time to say what you mean. They are a shorthand that people in general understand. Plus, in the age of smartphones, it really doesn’t do native English speakers any harm to have to look up the meanings of foreign words occasionally (I do this a lot). The other side of the coin (a phrase I’m used to seeing in print) is that with foreign phrases is it can be very amusing to say them in bad translations like “the Tour of France” (which I guess must be correct) or “piece of resistance” (which I am pretty sure isn’t). So as long as you are understood (assuming that you want to be understood) use them any way you like.

Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous. It’s hard to guess what George Orwell would have considered outright barbarous (and anyway, couldn’t he have cut “outright”?) but anyone reading books from even 30, 50 or a hundred years ago quickly sees that language evolves along with culture, so that rules – even useful ones – rarely have the permanence of commandments.

So much for Orwell’s rules; I was more heartened to find that something I’ve instinctively done – or not done – is supported by Orwell elsewhere. That is, that I prefer, mostly in the name of cringe-avoidance, not to use slang that post-dates my own youth. Even terms that have become part of normal mainstream usage (the most recent one is probably “woke”) tend to appear with inverted commas if I feel like I must use them, because if it’s not something I would be happy to say out loud (I say “woke” with inverted commas too) then I’d prefer not to write it. There is no very logical reason for this and words that I do comfortably use are no less subject to the whims of fashion, but still; the language you use is part of who you are, and I think Orwell makes a very good case here, (fuller version far below somewhere because even though I have reservations about parts of it it ends very well):

“Each generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it. This is an illusion, and one should recognise it as such, but one ought also to stick to one’s world-view, even at the price of seeming old-fashioned: for that world-view springs out of experiences that the younger generation has not had, and to abandon it is to kill one’s intellectual roots.”

Review of A Coat of Many Colours: Occasional Essays by Herbert Read. (1945) The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell Volume 4. Penguin 1968, p.72

Back to those two kinds* of people: I am the kind of person that likes and reads forewords, introductions, prefaces, author’s notes, footnotes, appendices, bibliographies, notes on the text, maps and all of those extras that make a book more interesting/informative/tedious.

*I know.

In one of my favourite films, Whit Stillman’s Metropolitan (1990), the protagonist Tom Townsend (Edward Clements), says “I don’t read novels. I prefer good literary criticism. That way you get both the novelists’ ideas as well as the critics’ thinking. With fiction I can never forget that none of it really happened, that it’s all just made up by the author.” Well, that is not me; but I do love a good bit of criticism and analysis as well as a good novel. One of my favourite pieces of writing of any kind, which I could (but choose not to) recite parts of by heart, is the late Anne Barton’s introduction to the 1980 New Penguin Shakespeare edition of Hamlet*.

*All of the New Penguin Shakespeare introductions that I’ve read have been good, but Barton’s is in a different league. John Dover Wilson’s What Happens in Hamlet (1935, though the edition I have mentions WW2 in the introduction, as I remember; I like the introduction) is sometimes easy to disagree with but it has a similar excitement-of-discovery tone to Anne Barton’s essay

I love Hamlet, and I’ve read it quite a few times, but I’ve read Barton’s introduction many more, to the point where phrases and passages have become part of my mind’s furniture. It’s a fascinating piece of writing, because Professor Barton had a fascinating range and depth of knowledge, as well as a passion for her subject; but also and most importantly because she was an excellent writer. If someone is a good enough writer* you don’t have to be interested in the subject to enjoy what they write.

* Good enough, schmood enough; what I really mean is if you like their writing enough. The world has always been full of good writers whose work leaves me cold

Beyond the introduction/footnote but related in a way are the review and essay. Another of my favourite books – mentioned elsewhere I’m sure, as it’s one of the reasons that I have been working as a music writer for the past decade and a half, is Charles Shaar Murray’s Shots from the Hip, a collection of articles and reviews. The relevant point here is that more than half of its articles – including some of my favourites – are about musicians whose work I’m quite keen never to hear under any circumstances, if humanly possible. Similarly, though I find it harder to read Martin Amis’s novels than I used to (just changing taste, not because I think they are less good), I love the collections of his articles, especially The War Against Cliché and Visiting Mrs Nabokov. I already go on about Orwell too much, but as I must have said somewhere, though I am a fan of his novels, it’s the journalism and criticism that he probably thought of as ephemeral that appeals to me the most.

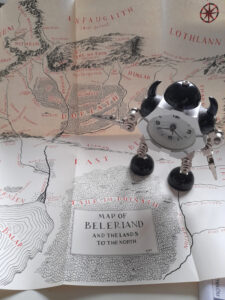

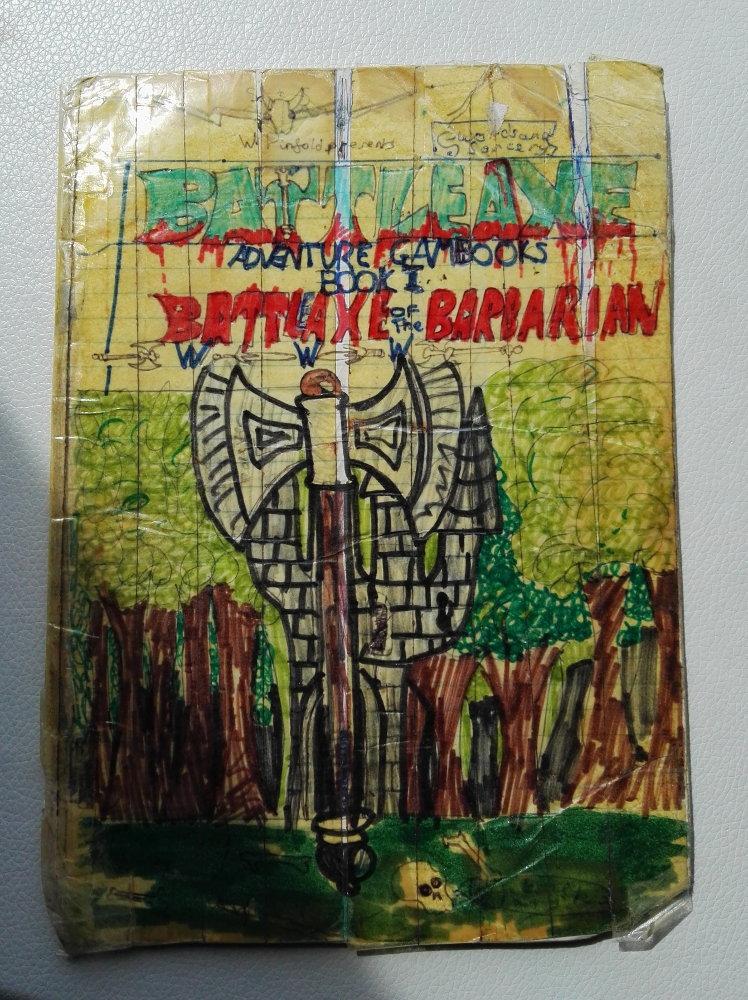

All this may have started – as I now realise that lots of things in my writing did – with Tolkien. From the first time I read his books myself, I loved that whatever part of Middle-Earth and its people you were interested in, there was always more to find out. Appendices, maps, whole books like The Silmarillion extended the enjoyment and deepened the immersion in Tolkien’s imaginary world. And they were central to that world – for Tolkien, mapping Middle-Earth was less making stuff up than it was a detailed exploration of something he had already at least half imagined. Maybe because I always wanted to be a writer myself – and here I am, writing – whenever I’ve really connected with a book, I’ve always wanted to know more. I’ve always been curious about the writer, the background, the process. I’ve mentioned Tintin lots of times in the past too and my favourite Tintin books were, inevitably, the expanded editions which included Herge’s sketches and ideas, the pictures and objects and texts that inspired him.

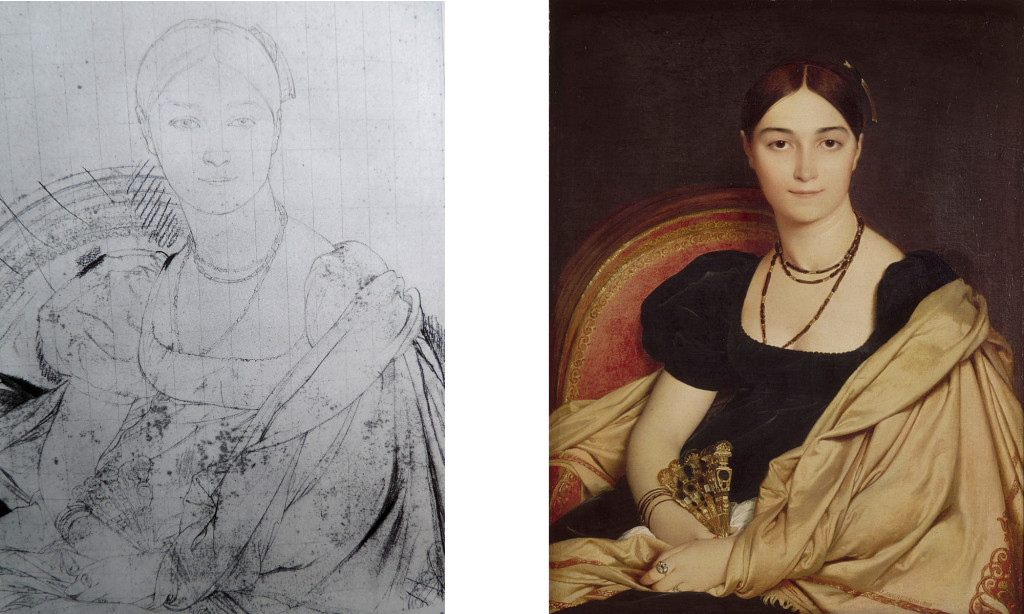

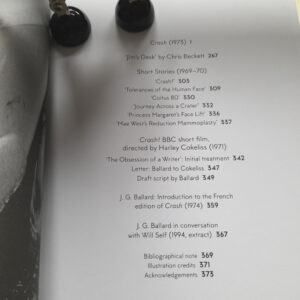

I first got one of those Tintin books when I was 9 or so, but as recently as the last few years I bought an in many ways similar expanded edition of one of my favourite books as an adult, JG Ballard’s Crash. It mirrors the Tintins pretty closely; explanatory essays, sketches, notes, ephemera, all kinds of related material. Now just imagine how amazing a graphic novel of Crash in the Belgian ligne claire style would be.*

*a bit like Frank Miller and Geof Darrow’s fantastic-looking, insanely detailed, but not all that memorable Hard Boiled (1990-92) I guess, only with fewer robots-with-guns shenanigans and more Elizabeth Taylor

A good introduction or foreword is (I think) important for a collection of poems or a historical text of whatever kind. Background and context and, to a lesser extent, analysis expand the understanding and enjoyment of those kinds of things. An introduction for a modern novel though is a slightly different thing and different also from explanatory notes, appendices and footnotes and it’s probably not by chance that they mainly appear in translations or reprints of books that already enjoyed some kind of zeitgeisty success.

When I first read Anne Barton’s introduction to Hamlet, I already knew what Hamlet was about, more or less. And while I don’t think “spoilers” are too much of an issue with fiction (except for whodunnits, which I have so far not managed to enjoy), do you really want to be told what to think of a book before you read it? But a really good introduction will never tell you that. If in doubt, read them afterwards!

Some authors, and many readers, see all of these extraneous things as excess baggage, surplus to requirements, which obviously they really are, and that’s fair enough. If the main text of a novel, a play or whatever, can’t stand on its own then no amount of post-production scaffolding will make it satisfactory.* And presumably, many readers pass their entire lives without finding out or caring why the author wrote what they wrote, or what a book’s place in the pantheon of literature is. Even as unassailably best-selling an author as Stephen King tends to be a little apologetic about the author’s notes that end so many of his books, despite the fact that nobody who doesn’t read them will ever know that he’s apologetic about them. Still; I for one would like to assure his publisher that should they ever decide to put together all of those notes, introductions and prefaces in book form, I’ll buy it. But would Stephen King be tempted to write an introduction for it?

* though of course it could still be interesting, like Kafka’s Amerika, Jane Austen’s Sanditon or Tolkien and Hergé (them again) with Unfinished Tales or Tintin and Alph-Art

That Orwell passage in full(er):

“Clearly the young and middle aged ought to try to appreciate one another. But one ought also to recognise that one’s aesthetic judgement is only fully valid between fairly well-defined dates. Not to admit this is to throw away the advantage that one derives from being born into one’s own particular time. Among people now alive there are two very sharp dividing lines. One is between those who can and can’t remember the period before 1914; the other is between those who were adults before 1933 and those who were not.* Other things being equal, who is likely to have a truer vision at the moment, a person of twenty or a person of fifty? One can’t say, though on some points posterity may decide. Each generation imagines itself to be more intelligent than the one that went before it, and wiser than the one that comes after it. This is an illusion, and one should recognise it as such, but one ought also to stick to one’s world-view, even at the price of seeming old-fashioned: for that world-view springs out of experiences that the younger generation has not had, and to abandon it is to kill one’s intellectual roots.”

*nowadays, the people who can or can’t remember life before the internet and those who were adults before 9/11? Or the Trump presidency? Something like that seems right

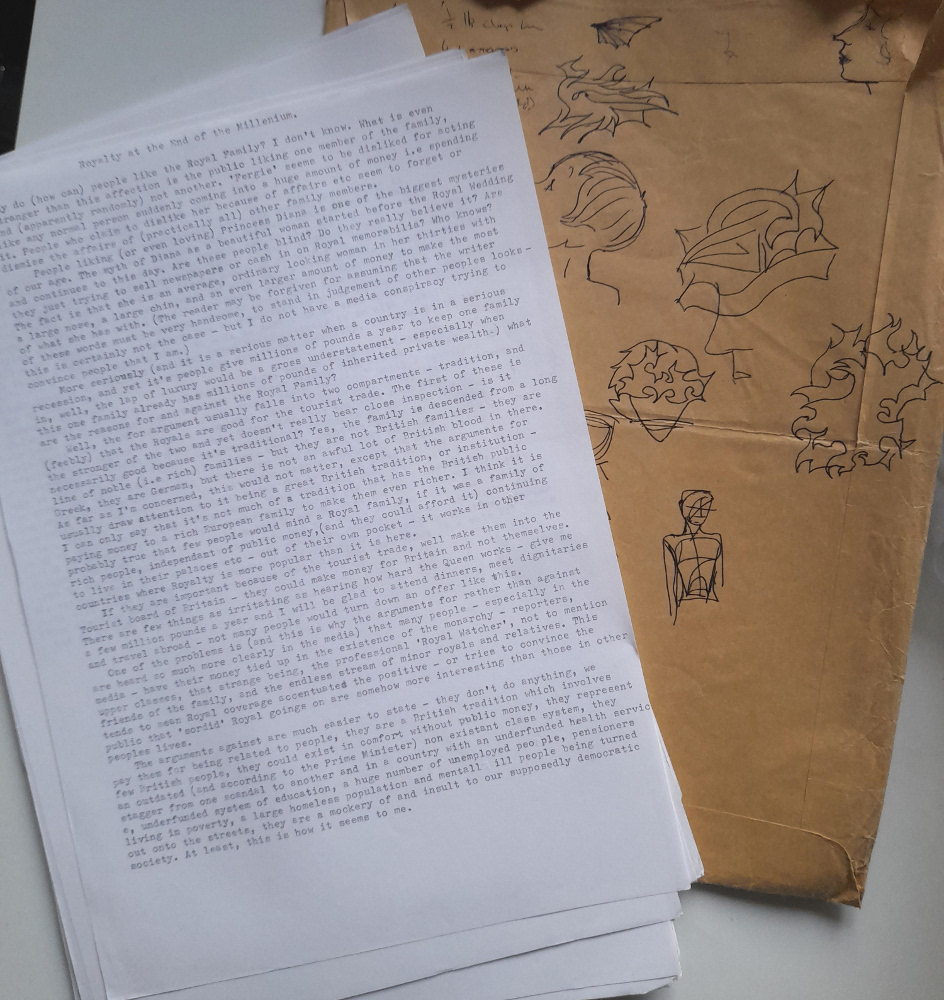

It’s funny; the arrogance and certainty of youth is well-known, but I’m still very surprised to find it in myself. I have rarely met anyone less sure of themselves or more reticent than my late-teens/early-20s self, but that doesn’t come across at all, except in a few deliberately self-deprecating caveats, and there’s an infuriating cockiness to some of the writing that I not only don’t identify with, but really hate; what’s mortifying is that I was genuinely trying to think deeply about the issues I covered so shallowly. Oh well, I hope I wasn’t actually that obnoxious in everyday life, but who knows? (anyone who knew me). On the other hand, my actual views don’t seem to have changed as much as I would have expected. I was more of a libertarian, albeit a left-wing one then, perhaps a bit more pessimistic, but on the whole I would still find myself on the same side of most of the arguments I am making, which is reassuring.

It’s funny; the arrogance and certainty of youth is well-known, but I’m still very surprised to find it in myself. I have rarely met anyone less sure of themselves or more reticent than my late-teens/early-20s self, but that doesn’t come across at all, except in a few deliberately self-deprecating caveats, and there’s an infuriating cockiness to some of the writing that I not only don’t identify with, but really hate; what’s mortifying is that I was genuinely trying to think deeply about the issues I covered so shallowly. Oh well, I hope I wasn’t actually that obnoxious in everyday life, but who knows? (anyone who knew me). On the other hand, my actual views don’t seem to have changed as much as I would have expected. I was more of a libertarian, albeit a left-wing one then, perhaps a bit more pessimistic, but on the whole I would still find myself on the same side of most of the arguments I am making, which is reassuring.