I intend to write something substantial for the site every month this year, but it’s nearly midnight on the 31st of January and nothing is finished for January, so here are some disparate notes and thoughts instead.

Despite the non-appearance of the big January post I’ve actually written quite a lot this January – 22, 546 words (not including these ones) in fact; that’s about half a novel, length-wise, but it was split between ten reviews, five articles of various types for my substack and, more unusually for me, a little bit of fiction.

In January I also enjoyed various things, so here are a few of them; I suppose you could think of them as recommendations, so the heading shall be…

Recommendations

I read several good books in January. One of them was Ramsey Campbell’s Scared Stiff, a collection of sex-themed short horror stories from the 80s. You may have come across some of my thoughts on Campbell before. The short version is; I want to like his work a little bit more than I generally do. He is I think the most critically acclaimed British horror author of his generation (unless you count Clive Barker, who was born just six years later but who seems to belong to a slightly younger generation. Maybe best to say that Campbell is the most acclaimed author of straightforward horror fiction of his generation, since at this point Barker’s reputation is based more on his imaginative/fantastical writing than his early horror work.) But anyway; Campbell is an acclaimed author and while I think that’s nice and I’m glad about it, more often than not I find there’s a surprisingly unremarked-on awkwardness to Campbell’s prose that mars it for me. Having said that, Scared Stiff included some of the best stories I’ve read by him and if it was a slightly mixed bag, it was a very enjoyable and genuinely chilling one, though I never really need to read the word ‘dwindled’ again.

I also read and enjoyed (in translation, naturally) Monsieur Proust by Céleste Albaret, which was fascinating and enlightening and occasionally (not Madame Albaret’s fault) a little disappointing. I’m very glad to have read it even though a little part of me preferred the Marcel I had imagined from reading his work to the more mundane but also much more rounded and believable human being that came across in Monsieur Proust. Almost the exact opposite happened when I read Andrew Graham-Dixon’s revelatory biography Vermeer – a Life Lost and Found, in which the mysterious and opaque Vermeer of the imagination. As Jonathan Richman sang in No One Was Like Vermeer (2008):

Vermeer was eerie

Vermeer was strange

He had a more modern colour range

As if born in another age

Like maybe a hundred or so years agoWhat’s this? A ghost in the gallery?

Great Scot! The Martians are here!

These strange little paintings next to the others

No-one was like Vermeer

Unexpectedly, to me at least, Andrew Graham-Dixon dispels much of the mystery, without undoing any of the magic; the Vermeer he describes is a man very specifically of his time and milieu, but ultimately to me that makes his particular kind of alchemy more rather than less extraordinary; maybe it’s just because I’m lacking in ‘negative capability,’ but for me knowing that the Girl With the Pearl Earring and the rest have a meaning and function that was highly specific to 17th century Delft, but which still communicate their human quality of warmth, empathy and connection down the ages is the miracle of art.

I also watched some good films this January, most recently, Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest (2023), which I had seen before, but watched two nights in a row, utterly hypnotised by it, just like the first time. By now it’s already a cliché to use the phrase ‘the banality of evil’ – but it also feels slightly wrong. In a way it’s the banality of the characters itself, especially Hedwig and Rudolf Höss, brilliantly played by Sandra Hüller and Christian Friedel – but also their children and the assorted businessmen and soldiers – that is what’s evil about them. At first it seems that to Rudolf Auschwitz is just his job, and to Hedwig it’s just her husband’s job – which is bad enough. But the genius of the film is the way that Glazer undercuts their blasé attitude by showing that they do understand not just the reality but the implications of what’s going on in the camp and that it’s not some kind of inexplicable mass hysteria; Hedwig’s own mother, though presumably just as unthinkingly loyal to her homeland and its government as her daughter is almost immediately struck by the utter wrongness of Auschwitz; Rudolf and Hedwig get it too; they just don’t mind.

The feeling of being hypnotised by a film is a rare one for me, but coincidentally(?) I watched two of the very few others that have that effect on me this January too. I watched Gus Van Sant’s Elephant (2003) several times last year and then watched it twice in January too. The first time the feeling is all about the suspense of not knowing how events will unfold, but obviously that can’t be true when rewatching it. And yet for me it remains just as appallingly gripping and sad every time, The same is true in a very different way of Oliver Hirschbiegel’s 2004 film Der Untergang. I watched that in January too, only once, but for the third or fourth time in the past few years. Key to its hypnotic quality is the great Bruno Ganz, but also the brilliant pacing, editing and performances of the whole cast. It feels like a thriller, even though it’s mostly people squabbling in a bunker.

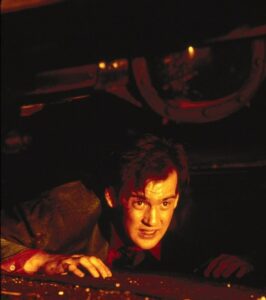

New to me though, was a film I’ve wanted to see since 1988 when I first read about it in (I’m fairly sure) FEAR magazine; a confusing memory because I clearly remember the picture of Anthony Edwards below (though in black and white), which is a still from the film. And I remember the headline was ‘Miner Miracles‘ and part of the article related to Steve Miner. But as far as I can see, Steve Miner (director of the great Warlock (1989) has nothing whatever to do with Miracle Mile, which was written and directed by Steve De Jarnatt. So maybe it was a general film roundup that mentioned both Miracle Mile and Warlock, which was definitely promoted in/by FEAR.

Anyway, I loved Miracle Mile and found it completely gripping and kind of sweet and heartbreaking and in a weird way nostalgic for the expected nuclear holocaust of my childhood. Partly it was nostalgic because it was like a cross between two different things from the 80s, both of which I love. Firstly, the kind of teen romance movie most associated with John Hughes (Pretty in Pink, Some Kind of Wonderful etc) and secondly Jimmy Murakami’s adaptation of Raymond Briggs’ cosily apocalyptic comicbook When the Wind Blows. I loved the glossy, 80s way it was filmed (especially the opening, idyllic shots of Miracle Mile itself) and its goofy humour and especially the two leads. I knew Anthony Edwards from a few things (though not his 80s work, oddly. I never liked and barely remember Revenge of the Nerds and I’ve never seen Top Gun) but I thought he was perfect in this; likeably dorky but also sincere – and I love Mare Winningham. She’ll always be Wendy from St Elmo’s Fire (1985 – one of my favourite 80s teen movies) to me, so it was strange at first, seeing her as cool-quirky rather than nerd-quirky. Anyway, loved it (and watched it three times). I’m glad/surprised the studio didn’t chicken out on the perfect ending. Oh. and it had the great Brian Thompson (Kabal from Doctor Mordrid) in a small but vital role; it couldn’t be more 80s and yet less typical of 80s Hollywood at the same time. Great Tangerine Dream soundtrack too.

Music-wise I heard a lot of things but especially liked a vast (101 track) compilation of bands associated with the legendary New York club CBGB, ranging from the obvious (Ramones, Blondie, Talking Heads, Patti Smith) to 70s oddballs like the Dictators and the Harlots of 42nd Street to classic 80s hardcore like Bad Brains and the early Beastie Boys. I’m cautiously excited about a reissue of Mactatus’s 1997 album Blot but haven’t gotten round to listening to it yet so don’t know if it’s retained it’s old potency. And I still haven’t listened to the new Ulver album, so there’s that.

Anyway; I’ll try to get at least one of those more substantial things finished and posted in February.

..

It’s not National, to my knowledge it’s rarely socialist, but it mostly is black metal; National Socialist Black Metal (hereafter, NSBM) annoys people by being ‘too evil’, or at least evil in the wrong way. As the snuff movie is to the horror movie, it seems, NSBM is to BM. There are a couple of flaws in this analogy; firstly, it suggests that black metal in general is, like horror movies, some kind of fantasy (which it certainly often is, but isn’t necessarily) and secondly, that NSBM isn’t some kind of fantasy (see previous parentheses). The Nazis of World War 2 represent the ‘ultimate evil’ to people of the post-war generations because whereas even the worst serial killers of the 20th century ‘worked’ on an individual, localised scale, the Nazis made murder into an ideology and ultimately an industry. That is, they functioned in ways that are relevant and relate-able to the daily lives and experiences of most people; but in bringing that mundane quality to extermination; ‘death factories’ they ultimately created something more frightening than a lone maniac. So is Nazi black metal the embodiment of that famously banal evil and therefore the ultimate in musical terrorism? Hmm, possibly not but let’s see…

It’s not National, to my knowledge it’s rarely socialist, but it mostly is black metal; National Socialist Black Metal (hereafter, NSBM) annoys people by being ‘too evil’, or at least evil in the wrong way. As the snuff movie is to the horror movie, it seems, NSBM is to BM. There are a couple of flaws in this analogy; firstly, it suggests that black metal in general is, like horror movies, some kind of fantasy (which it certainly often is, but isn’t necessarily) and secondly, that NSBM isn’t some kind of fantasy (see previous parentheses). The Nazis of World War 2 represent the ‘ultimate evil’ to people of the post-war generations because whereas even the worst serial killers of the 20th century ‘worked’ on an individual, localised scale, the Nazis made murder into an ideology and ultimately an industry. That is, they functioned in ways that are relevant and relate-able to the daily lives and experiences of most people; but in bringing that mundane quality to extermination; ‘death factories’ they ultimately created something more frightening than a lone maniac. So is Nazi black metal the embodiment of that famously banal evil and therefore the ultimate in musical terrorism? Hmm, possibly not but let’s see…