What was the first thing that scared you? The answer to that question is no doubt buried deep in your subconscious and could be almost anything. What was the first thing you sought out because you wanted to be scared? That should be easier to answer but for me at least, it isn’t really.

Well, there was Halloween, and Guy Fawkes Night still used to have a certain frisson in the days when effigies were burned on communal bonfires; an archaic-sounding memory now that November 5th is marked, if at all, by a few fireworks and now that Guy Fawkes has a new life as the face of anonymous protest, thanks to the weak movie adaptation of David Lloyd and Alan Moore’s classic graphic novel V for Vendetta. Whether many of the people using the likeness of “V” know that the real Fawkes’s aim was to restore an absolutist Catholic monarchy, rather than to restore power to the people, or whether most of them even know who Guy Fawkes was, I can’t say.

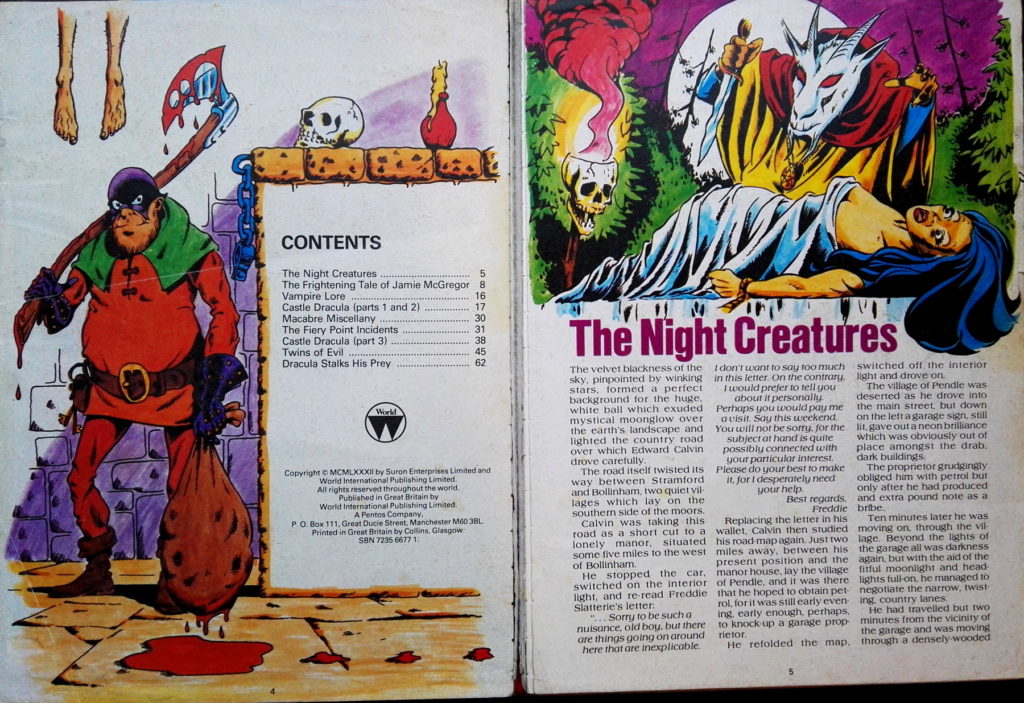

At some point in early childhood I became aware – as we all do – of the classic horror villains; Dracula, Frankenstein’s monster, werewolves, the mummy. Those same creatures in fact that, as horror film-loving adults, are famous as ‘the Universal monsters’ – an appropriate/fortuitous name as they are or at least were a kind of lingua franca for kids in the western world. But at the same time, it’s hard to say when exactly one became aware of them. I was bought (and still own), Dracula’s Spinechillers Annual (more about that here) for Christmas when I was eight – but that was hardly my introduction to Dracula. So what was? The earliest memories of these icons that I can pinpoint are parodies, things like The Munsters which, though already a couple of decades old were still regularly aired when I was a child. Then there was Carry On Screaming and of course specifically made-for-children cartoons like the Groovie Ghoulies – also of a certain vintage by then and the more up-to-date The Drac Pack. But although these were all light and funny, even when watching them as a young child, Dracula/Frankenstein/The Mummy etc remained first and foremost horror characters and the enjoyment of those comical versions depended on knowing about the ‘real’ ones. I remember thinking that The Drac Pack wasn’t scary enough. But compared to what?

In Dracula’s Spinechillers Annual – surely aimed squarely at the hardback annual audience (was this only a UK thing?), the same kids who bought, or were given, the Grange Hill Annual, the Beano or Dandy or Jackie or the annual Blue Peter book. And yet, in the Dracula annual there are beautifully drawn comic strip adaptations – as faithful as they can be for their brief length – of a couple of classic Hammer horror movies. Dracula (1958) and Twins of Evil (1971) were “x-rated” at the time of their release, but by the 80s would probably have been rated 15 – but even so, the comic adaptations come complete with titillating glimpses of nudity and splashes of blood that weren’t typical for kids annuals, to say the least. I hadn’t seen the movies at the time but I remember that even then I was aware of Hammer films, and thought of them as something old and harmless, rather than actually scary. I’d seen bits of them late at night on TV, mainly sequels; I saw Dracula, Prince of Darkness and The Scars of Dracula years before I ever saw the original, superior 1958 Dracula, but nothing from them sticks out much in my mind so, I can’t imagine I was particularly scared by them.

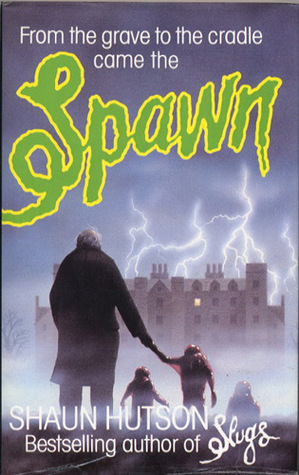

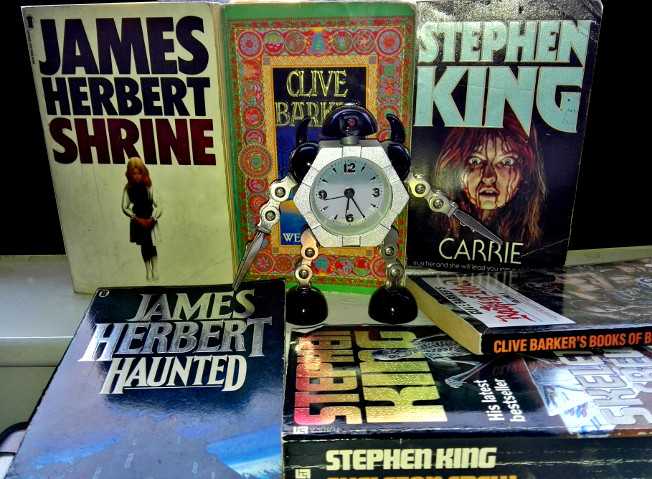

But at some point, as an older but still pre-teen child, I became a horror fan. While the theory of gateway drugs has been discredited regarding actual drugs, there’s a lot to be said for the idea in different contexts – as a teenage heavy metal fan you (it seemed inevitably) wanted to find music that was heavier, faster, more harsh. As a young reader of what passed for children’s horror fiction (I have the vaguest memories of enjoying Terrance Dicks’s Wereboy! and Cry Vampire! as mentioned here) you equally wanted to find ‘harder stuff’ – if not more scary, then at least more nasty and graphic. Which is not to say that (in either literature or music) you inevitably stick with the hard stuff; my liking for Stephen King long outlasted my liking for Shaun Hutson. In Hutson’s defence, his books were, as a teenager, ‘cool’ in a way that Stephen King’s only sporadically were, and although I don’t remember ever being actually scared by a Shaun Hutson book, he had other virtues; the pace, the energy, the humour – and to this day the opening of his 1983 classic Spawn (mentioned in various places, notably here) – my first encounter with his work – is the only time that reading a horror novel has made me feel physically sick. No wonder he became a favourite of my teenage years.

But I’m getting ahead of myself; if Shaun Hutson marked the zenith of my teenage horror addiction, the initial drug that set me on that road to excess happened a good few years earlier. There were children’s books borrowed from the library which for the most part didn’t really stay with me, although I remember the cover of a book of ghost stories I read then (surely edited by Peter Haining) vividly. As far as being scared goes, the things I remember most from childhood fall into the category of genuine not-fun fear (fear of older kids, skinheads, stuff like that) but also fun real-life fear; walking by a house where a ‘bad man’ lived, being on the streets at Halloween or (to some extent) Guy Fawkes night. The decline of November 5th is often attributed to the tightening of safety rules around fireworks, but I’d say its unique atmosphere actually died out just before that, when the making and burning of effigies (I still knew what “Penny for the Guy” was but I don’t remember kids of my generation doing that) was replaced by the bigger and more exciting (but less intimate and far less peculiar) spectacle of bigger and better communal firework displays.

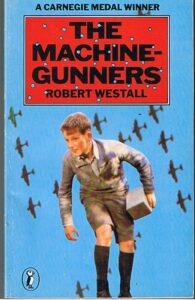

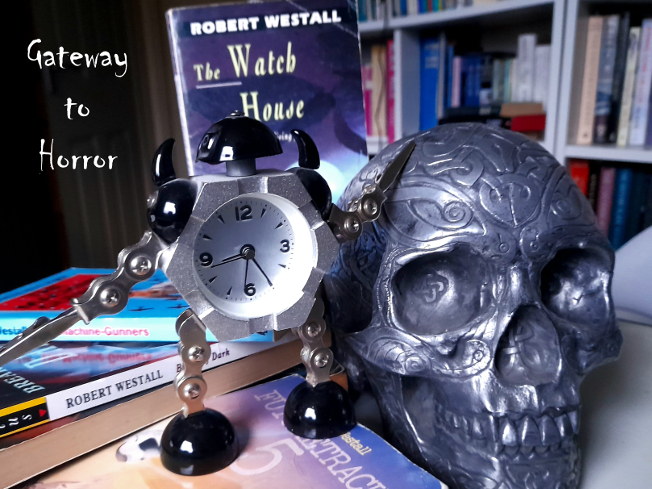

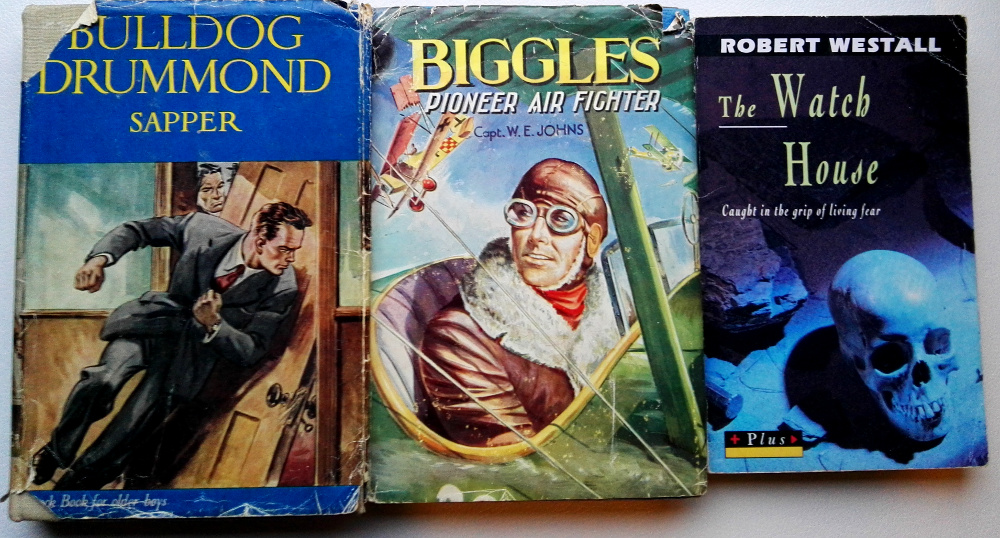

I was still at Primary school when I saw the first horror film that seemed genuinely creepy to me, The Omen. But it was essentially a dead end for a few years as primary school kids then had no way of accessing real horror movies, at least not without the collusion of adults and a budget beyond what I think was normal in my peer group. So my main route to being what could be termed a horror fan (though I don’t think it would occur to me at that point that it was a specific genre I was drawn towards) was through reading. There’s another story to be told that begins with the hugely popular Fighting Fantasy series of game books, which leads (with some help from Iron Maiden’s mascot Eddie; an important horror icon in his own way) towards HP Lovecraft, but for me, I think the real gateway drug that led me directly to Stephen King and James Herbert was Robert Westall.

Westall is best remembered now as a children’s author who wrote about WW2, and especially the Blitz. His most important book will probably always be his first, the iconic 1975 novel The Machine Gunners, winner of the Carnegie medal, which was made into an equally iconic TV show. And it deserves its fame – its story of a gang of Tyneside (actually, Garside; like most of his books The Machine Gunners is set in the fictional town of Garmouth, standing in for his own home town of Tynemouth) teenagers who ‘liberate’ a machine gun from a crashed German bomber plane and set up their own fortress to defend themselves and their town against the predicted Nazi invasion, in the face of what they see as the inadequate response of adult society to the situation. It remains both gripping and moving and is expertly told by a writer who had been a child during the war and was able to give a vivid account of the child’s eye view of ‘the home front,’ but who had also been a teacher with a teacher’s insight into children and their behaviour. Like most of the best children’s fiction it never talks down to its audience, and even allows its protagonists to swear when the realism of the story demands it, which was, quaintly, hugely impressive to children of the ‘80s.

The Machine Gunners TV series was broadcast when I was 9 and I first read the book around that time. It’s not a horror novel in any sense, but there are horrific elements within it. Aside from the general dread and tension of wartime, one scene in particular made a big impression on me, not only because of the gore, but also the subtly ominous build-up to the moment of horror, something which Westall would employ even more effectively in his horror-oriented novels. Near the start of the book, its hero Chas McGill has ventured into “The Wood” which

“was bleak and ugly[…] Some said it was haunted, but Chas had never found anything there but a feeling of cold misery, which wasn’t exciting like headless horsemen. Still, it was an oddly discouraging sort of place” (Machine Gunners, 1975, p.13)

This time though, Chas does find something; the remains of the tail end of a German bomber plane which has been shot down, but which still has its machine gun attached. He climbs the wreckage to get the gun, and the description of what happens next stayed with me for years:

“He peered over the edge of the cockpit.

The gunner was sitting there, watching him. One hand, in a soft fur mitt, was stretched up as if to retrieve the gun; the other lay in his overalled lap. … His right eye, pale grey, watched through the goggle-glass tolerantly and a little sadly. He looked a nice man, young.

The glass of the other goggle was gone. Its rim was thick with sticky red, and inside was a seething mass of flies, which rose and buzzed angrily at Chas’s arrival, then sank back into the goggle again.

For a terrible moment, Chas thought the Nazi was alive, that the mitted hand would reach out and grab him. Then, even worse, he knew he was dead.” (Machine Gunners 1975 p15)

After The Machine Gunners, the next Westall book I read was his excellent ‘Brave New 1984’-style dystopia Futuretrack 5 – again, not horror, but often horrifying, especially the scene near the beginning where the narrator Henry Kitson, head boy at an expensive public school, first becomes aware of the very different lives lived beyond the boundaries of his own privileged existence, and which for me entirely overshadowed the whole book when I first read it:

“… Peering through my jungle, I saw a man with no nose.

He’d had a nose; I could see where it had been. Now he just had two holes to breathe through. He’d no eyebrows either. Just purple rings around his eyes, making them look tiny and staring.”

(Futuretrack 5, 1985, p. 18)

This is Kitson’s first sight of an “Unem”, one of the army of unemployed who is killed shortly afterwards by the authorities. When Kitson asks his father what an Unem is (children asking adults awkward and difficult questions is a recurring theme throughout Westall’s books for children), the reply is chilling;

‘Shut up’, shouted my gentle father. ‘All you need to know is this – if you ever tell anybody what happened, you won’t have a home or a father or a mother.’ (Futuretrack 5, 1985, p.19-20)

After Futuretrack 5 I read as many Robert Westall books as I could get my hands on, and four in particular, all of which fit more or less within the horror genre, have stayed with me and at times unnerved me probably as much any book I’ve ever read has. In fact, they remain creepy now, if read in the right frame of mind, and are for me the most enjoyable of Westall’s many good books. Those four are The Wind Eye (1976), The Watch House (1977, now scandalously out of print), The Devil on the Road (1978; ditto) and The Scarecrows (1981), which, like The Machine Gunners, won the Carnegie medal. The Wind Eye is probably the least good of the four, but it has some powerful scenes. The action, which involves the bleak Northumbrian coastline, time travel, satanic goats and St Cuthbert, takes place when a troubled family (the central characters are three children from two broken marriages, whose incompatible parents have recently married) go to stay in the house of a distant and eccentric relative who has disappeared and been declared dead. But one of the book’s most effective moments comes right at the beginning, before the family even reaches the predictably ramshackle and spooky house:

“Oh, I’m shocking our little Christian here. So unlike her beloved Father. Don’t be such a prig, Beth. It doesn’t mean a thing.” And she placed her blue shoe on the black marble slab.

Nothing moved; nothing fell. But in that instant Beth knew that someone had become aware of them.” (The Wind Eye, 1976, p.12)

This anticipates some of Westall’s most creepy moments, especially a key scene in The Scarecrows, but although The Wind Eye builds to an appropriately stormy and tempestuous climax, The Watch House is far more effectively chilling throughout, probably because, like Westall’s later horror-oriented novels, the action revolves around a single, complex and isolated character rather than a group.

The Watch House, which, like The Machine Gunners, was the subject of a TV series – though a sadly inferior and often laughable one – is the most traditional of Westall’s horror novels. The book is a kind of haunted house story, where a troubled teenage girl, away from home while her parents go through a difficult separation, becomes the focus of ghostly activity. The haunting initially centres around the Watch House, the somewhat dilapidated home of the Garmouth Volunteer Life Brigade, a kind of down-at-heel, local RNLI founded when the town was still a busy fishing port.

The atmosphere, landscape and ingredients of the story are established with skillful economy within the first few pages as the heroine Anne, driven by her spoiled and unsympathetic mother, arrives in Garmouth, where she is to be dumped on her mother’s old nanny for the holidays while the separation is hammered out at home. Garmouth, already depicted in The Machine Gunners as a town whose best years perhaps lay behind it, even in the 40s, is seen in more detail here. It’s a typical fishing town, still busy but slightly dowdy in the recession years of 1970s Britain. Decay is everywhere; Anne is introduced early on to the Black Middens, great rocks in the estuary of the Gar, historically the source of the shipwrecks which are at the book’s heart, but now tamed by great concrete piers. A sea wall, begun but discontinued when funding ran out, snakes along the foot of the cliffs on which the Watch House stands. The cliffs are crumbling, as are the ruins of a medieval priory with its slightly dilapidated coastal graveyard; “The sea must eat away the cliff, thought Anne. Some wild nights, bones long buried in earth must receive final burial in sea.” (The Watch House, 1977, p.10)

And then of course there’s the Watch House itself, established almost immediately as a sinister, but fascinating and alluring presence:

“The road ended at the Watch House, which loomed over them as they got out of the car. Built of long white planks, sagging with the years, it had a maritime look. Like a mastless, roofed-in schooner becalmed in a sea of dead grass. Through its windows showed a dark clutter of things that couldn’t be recognised. This clutter and a lack of curtains made the windows look like eyes in a white planked face.” … “The Watch House was well-named. It did seem to watch you. But it was only the effect of dark windows in white walls.” (The Watch House, 1977, p.10-11)

For the first two parts of the novel, the Watch House is at the centre of the supernatural action. A working base for the now-rarely-needed Life Brigade, by this time a group of old, retired men, it also houses their memorabilia. Like the house in The Wind Eye it’s full of fascinating curios. But whereas the house had belonged to one man with a fascination for the past, the Watch House is a repository for generations’ worth of knick-knacks; old photographs, items rescued from shipwrecks, ship’s figureheads, even the bones of the dead found among the Black Middens but never identified. Initially a project for Anne to pass the time, the cleaning, organising and documenting of the Watch House’s contents becomes an obsession and initiates the connection between Anne and a ghostly presence, known affectionately to the members of the Brigade, as ‘the Old Feller.’ Hitherto known and only half believed-in as a somewhat playful spirit who knocks things over and leaves messages in the dust, when Anne arrives his messages become frequent and unambiguously urgent and personal; they are a cry for help.

Anne’s status as a sympathetic outsider, as well as the somewhat lonely figure at is reinforced throughout the novel, where the other characters are almost all arranged around her in paired opposites. There are Purdie and Arthur, the elderly couple she is staying with, she old fashioned and disapproving, he mischievous and childlike; the friends Anne makes, Pat and Timmo, Pat cosy and docile, the simian Timmo energetic, cerebral and inquisitive; the two clergymen, Father Fletcher – the local Church of England vicar, cheerful, straightforward and relaxed, and Father da Souza, an American Catholic priest, fiery, dynamic and antagonistic. Even Anne’s parents, peripheral but essential elements in the story, fit in with this pattern, Anne’s mother is fashionable, demanding, cold and impatient while her father – who barely appears – is warm, caring, disorganised and ultimately, perhaps a less sympathetic figure than the author intends. Finally, there are the ghosts themselves; the Old Feller, harmless, terrified and childlike, and the real villain, the ghost of a murderous army officer named Hague, who is bullying, menacing and violent. In each of these cases Anne comes between the other characters, at times more-or-less harmoniously (keeping the peace between Purdie and Arthur and Pat and Timmo) and at others inadvertently stoking tension.

Anne’s own personality, less flamboyant than most of the cast, is mainly brought out in contrast with the others and essentially we see her as an ordinary, lonely teenager. She’s clever and industrious, mild-mannered, but also easily bored. There’s a sharper side to her nature too, mainly expressed when her mother is around, which can be surprising and no doubt helped to earned the book its Puffin Plus (older children and teens) status. We meet this side of Anne right at the beginning of the novel, when, approaching Garmouth, her mother warns her about Arthur;

“Never made anything of himself, even by their standards. He takes advantage, given half a chance. You’ll need to watch him.”

“What is he – a rapist?”

“I wish you wouldn’t talk like that” (The Watch House p.9)

Anne, already not thrilled at this enforced holiday with near-strangers, is clearly trying to antagonise her mother, but as we discover, her cynicism is well-founded, not because of Arthur himself (who is a harmless, if irritatingly childish old man), but because she is used to the unwanted attentions of her mother’s boyfriend, the loathsome “Uncle Monty”. Late in the novel, when her mother threatens to take her home to London:

“’I don’t want to live with you. I can’t stand having that man around the place the whole time.”

[…] “You mean Uncle Monty? He’s just a friend, you silly goose. He’s just helping me settle in, that’s all.’

‘By spending all night in your bedroom while Daddy’s away? […] He can’t keep his hands off me either. He’s always trying to touch me, when you’re not watching. And give me wet open-mouth kisses.’ It was true. So why was it so terrible to say it?” (The Watch House, p.158)

We are reminded throughout the book that Anne is a teenager and not a child; she is at her most teenager-ish when she goes to the local Youth Club disco in the hope of meeting people her own age:

“She’d thought hard what to wear at the Youth Club, and finally decided on plain Wranglers with a Wrangler top. […] Nothing for little cats to get their tongues around; nothing for them to pick holes in. Course, they’d pick holes anyway. But not such painful ones.” [The Watch House, p.65]

Initially, all of the ghostly activity happens within the Watch House itself and takes the form of writing in the dust on the display cases and flickering lights, but when, a few years after reading The Watch House, I first read Stephen King’s IT, the scenes where that novel’s young protagonists first encounter Pennywise irresistibly reminded me of Anne’s first unambiguous encounter with ghosts after the Garmouth carnival, a beautifully effective and atmospheric piece of writing:

“As she got further along the pier, and the sky darkened, the family groups thinned out. She passed through the last, and was alone. Except for one small person in Victorian top-hat and frock-coat, hurrying ahead of her towards the lighthouse. Head down and hands behind his back. Alone among the crowds he looked anxious. He kept peering over his shoulder at her, his face a white blur in the dusk.

[…]

Didn’t she know him?

Of course not. It was just that he looked like that picture of Isembard Kingdom Brunel, who built the Great Western. Except Brunel had looked so much cockier with that big cigar. Not so scared…

And then she knew, quite certainly, that she was looking at a ghost. Because the light on the South Pier came on, and shone right through his face.

[…]

‘It’s me, Anne,’ she took a step forward.

The ghost writhed away.

‘Whatever’s the matter?’ Her voice rose to a scared shriek.

This had happened before to her. Where? Where? In the orchard with Cousin Jane. She had walked towards Cousin Jane, and Jane had shrieked with terror. Because Anne, all unknowing, had a spider in her hair, and Jane was terrified of spiders.

[…]

Anne whirled round. Something faded round the curve of the lighthouse. Something red. There was a strong gust of seaweed; the smell of the bottom of a river.

[…]

She tried doubling back. Nothing. The Old Feller was gone. She was alone with something red that stank of the river and had terrified a ghost.” (The Watch House p.116-7)

During the first two acts of the novel, Westall expertly raises the tension and confounds expectations, the simple haunting becoming something more complex and less predictable as Anne’s not-always-harmonious relationship with her newfound friends complicates things further. Then, as we enter the novel’s final phase, The Watch House has a feature that I’ve always loved in horror novels and one which I associate with (again) IT in particular – the period of research, usually during a lull in horrific activity after the threat has been established. In The Watch House, Anne initially assumes that the ghost – The Old Feller – is trying to engage her help to save the Watch House – which he, as founder of the Garmouth Volunteer Life Brigade had built – from financial and physical ruin and by extension save the Life Brigade itself. But once Anne has helped to secure the future of the Watch House as a museum and the hauntings don’t stop, it becomes clear that more than one spirit is involved.

After a session of hypnosis with her new friends Pat and Timmo proves both disturbing and revealing it becomes clear that understanding the problem requires more detailed local knowledge than Anne has. She talks to the oldest member of the life Brigade, the 95-year-old Bosun, who gives her an eye witness account of events she has previously seen under hypnosis, through the Old Feller’s eyes. She again enlists the help of Timmo. Introduced in the guise of ‘Doctor Death’, an eccentric DJ running the youth club disco, Timmo is an older teenager, a medical student with a huge variety of interests and expertise, but no real attention span. Timmo is knowledgable and freakishly intelligent, but his interest in the paranormal is as playful and skeptical rather as it is genuine and after the dramatic first hypnosis session, Anne only reluctantly agrees to do it again. Before that happens, Anne insists on some more concrete research, but as is common during these kinds of interludes in horror fiction, she suffers from a sense of dislocation that makes rational thought difficult:

“Next morning, Timmo had to bully her all the way up the hill to Front Street. If he hadn’t called for her, she would never have got out of bed. Her legs felt like lead; she had hardly slept.

Front Street, full of shoppers and red double-decker buses, was insubstantial, like a dream. It was the real world that was ghostly now.” (The Watch House, p.131)

The novel’s final act brings the story to a feverish pitch as the supernatural events become more deadly and Anne’s mother arrives in Garmouth, threatening to take her back to London. The climax, involving the two priests in an extended exorcism – surely influenced by the final scenes in the movie version of William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist – is powerful but, like the ending of this article, a little bathetic. Although narratively satisfying, it’s loud and apocalyptic where the novel’s most effectively eerie moments are quiet and understated. The scenes that lingered in my mind – and which remain the most vivid to me decades later – are those when Anne, alone in the Watch House, is menaced by Hague, or when she is stalked by a mangy, grave-digging dog in the old Priory churchyard. As horror fiction, these are among the finest scenes that Westall ever wrote. Anne too, is a surprisingly vivid and sympathetic character; Westall’s female characters are often on the verge of caricature and his usual (youthful, male) protagonists tend to have a manly impatience with the women in his books. I would hesitate to call Westall’s books misogynistic, but there is sometimes a strain of male chauvinism to them which seems to belong to the author as much as it does to the characters. It’s also an oddity perhaps worth mentioning that of all the books I read as a child – and there were quite lot of them – Westall’s are the only ones I recall which almost invariably have a flippant reference to rape in them, which definitely feels bizarre in the 21st century. The Watch House itself is very much a product of the 1970s – with much that that entails; chauvinism, mild homophobia, flared trousers – in a way that The Machine Gunners wasn’t, which possibly accounts for its currently out-of-print status. But it’s a shame, with some kind of preface/disclaimer about its dated attitudes and language, it could easily go on to scare new generations of children, and get them hooked on the mysterious delights of the horror genre.

the Mobile Library (itself a very 80s detail although I’m sure they still exist) and loving them, and, later in Primary School Robert Westall’s The Scarecrows, The Watch House, The Wind Eye and The Devil on the Road made a big impression on me (and still stand up well when read as an adult). As a devotee of the phenomenally successful Fighting Fantasy gamebook series, I recall being particularly impressed by the horror-themed House Of Hell, which was very different from the swords & sorcery (or sci fi) leanings of the rest of the series.

the Mobile Library (itself a very 80s detail although I’m sure they still exist) and loving them, and, later in Primary School Robert Westall’s The Scarecrows, The Watch House, The Wind Eye and The Devil on the Road made a big impression on me (and still stand up well when read as an adult). As a devotee of the phenomenally successful Fighting Fantasy gamebook series, I recall being particularly impressed by the horror-themed House Of Hell, which was very different from the swords & sorcery (or sci fi) leanings of the rest of the series.