When I was a child there was music which was, whether you liked it or not, inescapable. I have never – and this is not a boast – deliberately or actively listened to a song by Michael Jackson, Madonna, Phil Collins, Duran Duran, Roxette, Take That, Bon Jovi, the Spice Girls… the list isn’t endless, but it is quite long. And yet I know some, or a lot, of songs by all of those artists. And those are just some of the household names. Likewise I have never deliberately listened to “A Horse With No Name” by America, “One Night in Bangkok” by Murray Head or “Would I Lie to You” by Charles & Eddie; and yet, there they are, readily accessible should I wish (I shouldn’t) to hum, whistle or sing them, or just have them play in my head, which I seemingly have little control over.

And yet, since the dawn of the 21st century, major stars come and go, like Justin Bieber, or just stay, like Ed Sheeran, Lana Del Rey or Taylor Swift, without ever really entering my consciousness or troubling my ears. I have consulted with samples of “the youth” to see if it’s just me, but no: like me, there are major stars that they have mental images of, but unless they have actively been fans, they couldn’t necessarily tell you the titles of any of their songs and have little to no idea of what they actually sound like. Logical, because they were no more interested in them than I was in Dire Straits or Black Lace; but alas, I know the hits of Dire Straits and Black Lace. And the idea of ‘the Top 40 singles chart’ really has little place in their idea of popular music. Again, ignorance is nothing to be proud of and I literally don’t know what I’m missing. At least my parents could dismiss Madonna or Boy George on the basis that they didn’t like their music. It’s an especially odd situation to find myself in as my main occupation is actually writing about music; but of course, nothing except my own attitude is stopping me from finding out about these artists.

The fact is that no musician is inescapable now. Music is everywhere, and far more accessibly so than it was in the 80s or 90s – and not just new music. If I want to hear Joy Division playing live when they were still called Warsaw or track down the records the Wu-Tang Clan sampled or hear the different version of the Smiths’ first album produced by Troy Tate, it takes as long about as long to find them as it does to type those words into your phone. Back then, if you had a Walkman you could play tapes, but you had to have the tape (or CD – I know CDs are having a minor renaissance, but is there any more misbegotten, less lamented creature than the CD Walkman?) Or you could – from the 1950s onwards – carry a radio with you and listen to whatever happened to be playing at the time. I imagine fewer people listen to the radio now than they did even 30 years ago, but paradoxically, though there are probably many more – and many more specialised – radio stations now than ever, their specialisation actually feeds the escapability of pop music. Because if I want to hear r’n’b or metal or rap or techno without hearing anything else, or to hear 60s or 70s or 80s or 90s pop without having to put up with their modern-day equivalents, then that’s what I and anyone else will do. I have never wanted to hear “Concrete and Clay” by Unit 4+2 or “Agadoo” or “Come On Eileen” or “Your Woman” by White Town or (god knows) “Crocodile Shoes” by Jimmy Nail; but there was a time when hearing things I wanted to hear but didn’t own, meant running the risk of being subjected to these, and many other unwanted songs. As I write these words, “Owner of a Lonely Heart” by Yes, a song that until recently I didn’t know I knew is playing in my head.

And so, the music library in my head is bigger and more diverse than I ever intended it to be. In a situation where there were only three or four TV channels and a handful of popular radio stations, music was a kind of lingua franca for people, especially for young people. Watching Top of the Pops on a Thursday evening, or later The Word on Friday was so standard among my age group that you could assume that most people you knew had seen what you saw; that’s a powerful, not necessarily bonding experience, but a bond of sorts, that I don’t see an equivalent for now, simply because even if everyone you know watches Netflix, there’s no reason for them to have watched the same thing at the same time as you did. It’s not worse, in some ways it’s obviously better; but it is different. Of course, personal taste back then was still personal taste, and anything not in the mainstream was obscure in a way that no music, however weird or niche, is now obscure, but that was another identity-building thing, whether one liked it or not.

Growing up in a time when this isn’t the case and the only music kids are subjected to is the taste of their parents (admittedly, a minefield) or fragments of songs on TV ads, if they watch normal TV or on TikTok, if they happen to use Tiktok, is a vastly different thing. Taylor Swift is as inescapable a presence now, much as Madonna was in the 80s, but her music is almost entirely avoidable and it seems probable that few teenagers who are entirely uninterested in her now will find her hits popping unbidden into their heads in middle age. But conversely, the kids of today are more likely to come across “Owner of a Lonely Heart” on YouTube than I would have been to hear one of the big pop hits of 1943 in the 80s.

What this means for the future I don’t know; but surely its implications for pop-culture nostalgia – which has grown from its humble origins in the 60s to an all-encompassing industry, are huge. In the 60s, there was a brief fashion for all things 1920s and 30s which prefigures the waves of nostalgia that have happened ever since. But for a variety of reasons, some technical, some generational and some commercial, pop culture nostalgia is far more elaborate than ever before. We live in a time when constructs like “The 80s” and “The 90s” are well-defined, marketable eras that mean something to people who weren’t born then, in quite a different way from the 1960s version of the 1920s. Even back then, the entertainment industry could conjure bygone times with an easy shorthand; the 1960s version of the 1920s and 30s meant flappers and cloche hats and Prohibition and the Charleston and was evoked on records like The Beatles’ Honey Pie and seen onstage in The Boy Friend or in the cinema in Bonnie & Clyde. But the actual music of the 20s and 30s was mostly not relatable to youngsters in the way that the actual entertainment of the 80s and 90s still is. Even if a teenager in the 60s did want to watch actual silent movies or listen to actual 20s jazz or dance bands they would have to find some way of accessing them. In the pre-home video era that meant relying on silent movie revivals in cinemas, or finding old records and having the right equipment to play them on, since old music was then only slowly being reissued in modern formats. The modern teen who loves “the 80s” or “the 90s” is spoiled by comparison, not least because its major movie franchises like Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Ghostbusters and Jurassic Park are still around and its major musical stars still tour or at least have videos and back catalogues that can be accessed online, often for free.

Fashion has always been cyclical, but this feels quite new (which doesn’t mean it is though). Currently, culture feels not like a wasteland but like Eliot’s actual Waste Land, a dissonant kind of poetic collage full of meaning and detritus and feeling and substance and ephemera but at first glance strangely shapeless. For example, in one of our current pop culture timestreams there seems to be a kind of 90s revival going on, with not only architects of Britpop like the Gallagher brothers and Blur still active, but even minor bands like Shed Seven not only touring the nostalgia circuit but actually getting in the charts. Britpop was notoriously derivative of the past, especially the 60s and 70s. And so, some teenagers and young adults (none of these things being as pervasive as they once were) are now growing up in a time when part of ‘the culture’ is a version of the culture of the 90s, which had reacted to the culture of the 80s by absorbing elements of the culture of the 60s and 70s. And while the artists of 20 or 30 years ago refuse to go away even modern artists from alternative rock to mainstream pop stars make music infused with the sound of 80s synths and 90s rock and so on and on. Nothing wrong with that of course, but what do you call post-post-modernism? And what will the 2020s revival look like when it rears its head in the 2050s, assuming there is a 2050s? Something half interesting, half familiar no doubt.

2023 was the usual mixed bag of things; I didn’t see any of the big movies of

2023 was the usual mixed bag of things; I didn’t see any of the big movies of the year yet. I have watched half of Saltburn, which so far makes me think of the early books of Martin Amis, especially Dead Babies (1975) and Success (1978) – partly because I read them again after he died last year. They are both still good/nasty/funny, especially Success, but whereas I find that having no likeable characters in a book is one thing, and doesn’t stop the book from being entertaining, watching unlikeable characters in a film is different – more like spending time with actual unlikeable people, perhaps because – especially in a film like Saltburn – you can only guess at their motivations and inner life. So, the second half of Saltburn remains unwatched – but I liked it enough that I will watch it.

the year yet. I have watched half of Saltburn, which so far makes me think of the early books of Martin Amis, especially Dead Babies (1975) and Success (1978) – partly because I read them again after he died last year. They are both still good/nasty/funny, especially Success, but whereas I find that having no likeable characters in a book is one thing, and doesn’t stop the book from being entertaining, watching unlikeable characters in a film is different – more like spending time with actual unlikeable people, perhaps because – especially in a film like Saltburn – you can only guess at their motivations and inner life. So, the second half of Saltburn remains unwatched – but I liked it enough that I will watch it.

I read lots of good books in 2023 – I started keeping a list but forgot about it at some point – but the two that stand out in my memory as my favourites are both non-fiction. Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art is completely engrossing and full of exciting ways of really looking at pictures. I wrote at length about Elena Kostyuchenko’s I Love Russia

I read lots of good books in 2023 – I started keeping a list but forgot about it at some point – but the two that stand out in my memory as my favourites are both non-fiction. Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art is completely engrossing and full of exciting ways of really looking at pictures. I wrote at length about Elena Kostyuchenko’s I Love Russia  It’s no great surprise to me that my favourite books of the year would be – like much of my favourite art – by women. Though I think the individual voice is crucial in all of the arts, individuals don’t grow in a vacuum and because female (and, more widely, non-male) voices and viewpoints have always been overlooked, excluded, marginalised and/or patronised, women and those outside of the standard, traditional male authority figures more generally, tend to have more interesting and insightful perspectives than the ‘industry standard’ artist or commentator does. The first time that thought really struck me was when I was a student, reading about Berlin Dada and finding that Hannah Höch was obviously a much more interesting and articulate artist than (though I love his work too) her partner Raoul Hausmann, but that Hausmann had always occupied a position of authority and a reputation as an innovator, where she had little-to-none. And the more you look the more you see examples of the same thing. In fact, because women occupied – and in many ways still occupy – more culturally precarious positions than men, that position informs their work – thinking for example of artists like Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage or – a bigger name now – Frida Kahlo – giving it layers of meaning inaccessible to – because unexperienced by – their male peers.

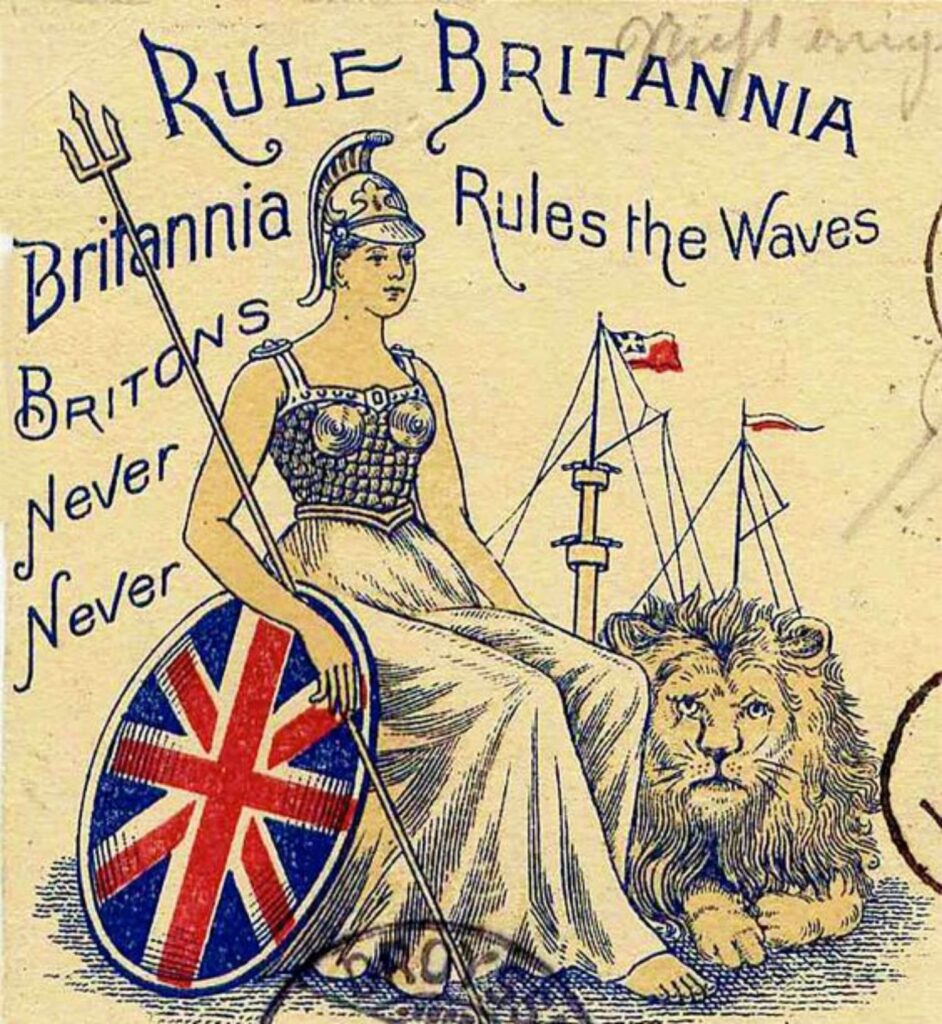

It’s no great surprise to me that my favourite books of the year would be – like much of my favourite art – by women. Though I think the individual voice is crucial in all of the arts, individuals don’t grow in a vacuum and because female (and, more widely, non-male) voices and viewpoints have always been overlooked, excluded, marginalised and/or patronised, women and those outside of the standard, traditional male authority figures more generally, tend to have more interesting and insightful perspectives than the ‘industry standard’ artist or commentator does. The first time that thought really struck me was when I was a student, reading about Berlin Dada and finding that Hannah Höch was obviously a much more interesting and articulate artist than (though I love his work too) her partner Raoul Hausmann, but that Hausmann had always occupied a position of authority and a reputation as an innovator, where she had little-to-none. And the more you look the more you see examples of the same thing. In fact, because women occupied – and in many ways still occupy – more culturally precarious positions than men, that position informs their work – thinking for example of artists like Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage or – a bigger name now – Frida Kahlo – giving it layers of meaning inaccessible to – because unexperienced by – their male peers. If that backlash comes, it will be from the academic equivalent of those figures who, in 2023 continued to dominate the cultural landscape. These are conservative (even if theoretically radical) people who pride themselves on their superior rational, unsentimental and “common sense” outlook, but whose views tend to have a surprising amount in common with some of the more wayward religious cults. Subscribing to shallowly Darwinist ideas, but only insofar as they reinforce one’s own prejudices and somehow never feeling the need to follow them to their logical conclusions is not new, but it’s very now. Underlying ideas like the ‘survival of the fittest’, which then leads to the more malevolent idea of discouraging the “weak” in society by abolishing any kind of social structure that might support them is classic conservatism in an almost 19th century way, but somehow it’s not surprising to see these views gaining traction in the discourse of the apparently futuristic world of technology. In more that one way, these kinds of traditionalist, rigidly binary political and social philosophies work exactly like religious cults, with their apparently arbitrary cut off points for when it was that progress peaked/halted and civilisation turned bad. That point varies; but to believe things were once good but are now bad must always be problematic, because when, by any objective standards, was everything good, or were even most things good? For a certain class of British politician that point seems to have been World War Two, which kind of requires one to ignore actual World War Two. But the whole of history is infected by this kind of thinking – hence strange, disingenuous debates about how bad/how normal Empite, colonialism or slavery were; incidentially, you don’t even need to read the words of abolitionists or slaves themselves (though both would be good to read) to gain a perspective of whether or not slavery was considered ‘normal’ or bad by the standards of the time. Just look at the lyrics to Britain’s most celebratory, triumphalist song of the 18th century, Rule Britannia. James Thomson didn’t write “Britons never, never, never shall be slaves; though there’s nothing inherently wrong with slavery.” They knew it was something shameful, something to be dreaded, even while celebrating it.

If that backlash comes, it will be from the academic equivalent of those figures who, in 2023 continued to dominate the cultural landscape. These are conservative (even if theoretically radical) people who pride themselves on their superior rational, unsentimental and “common sense” outlook, but whose views tend to have a surprising amount in common with some of the more wayward religious cults. Subscribing to shallowly Darwinist ideas, but only insofar as they reinforce one’s own prejudices and somehow never feeling the need to follow them to their logical conclusions is not new, but it’s very now. Underlying ideas like the ‘survival of the fittest’, which then leads to the more malevolent idea of discouraging the “weak” in society by abolishing any kind of social structure that might support them is classic conservatism in an almost 19th century way, but somehow it’s not surprising to see these views gaining traction in the discourse of the apparently futuristic world of technology. In more that one way, these kinds of traditionalist, rigidly binary political and social philosophies work exactly like religious cults, with their apparently arbitrary cut off points for when it was that progress peaked/halted and civilisation turned bad. That point varies; but to believe things were once good but are now bad must always be problematic, because when, by any objective standards, was everything good, or were even most things good? For a certain class of British politician that point seems to have been World War Two, which kind of requires one to ignore actual World War Two. But the whole of history is infected by this kind of thinking – hence strange, disingenuous debates about how bad/how normal Empite, colonialism or slavery were; incidentially, you don’t even need to read the words of abolitionists or slaves themselves (though both would be good to read) to gain a perspective of whether or not slavery was considered ‘normal’ or bad by the standards of the time. Just look at the lyrics to Britain’s most celebratory, triumphalist song of the 18th century, Rule Britannia. James Thomson didn’t write “Britons never, never, never shall be slaves; though there’s nothing inherently wrong with slavery.” They knew it was something shameful, something to be dreaded, even while celebrating it.

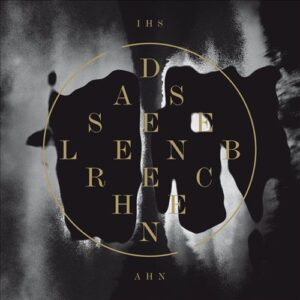

My favourite album of that year was Ihsahn’s Das Seelenbrechen, and it’s still one of my favourite albums. I rarely listen to it all the way through at the moment, but various tracks, such as Pulse, Regen and NaCL are still in regular rotation

My favourite album of that year was Ihsahn’s Das Seelenbrechen, and it’s still one of my favourite albums. I rarely listen to it all the way through at the moment, but various tracks, such as Pulse, Regen and NaCL are still in regular rotation My favourite album of 2014 was

My favourite album of 2014 was My album of 2015 was Life is a Struggle, Give Up by

My album of 2015 was Life is a Struggle, Give Up by

I wouldn’t necessarily say I was aware of it at the time, but 2016 was a great year for music. My album of the year was Wyatt at the Coyote Palace by Kristin Hersh (which I enthused about

I wouldn’t necessarily say I was aware of it at the time, but 2016 was a great year for music. My album of the year was Wyatt at the Coyote Palace by Kristin Hersh (which I enthused about

2017 had fewer standouts for me but my album of the year, the self-titled debut by Finnish alt-rock band Ghost World, which I wrote enthusiastically about

2017 had fewer standouts for me but my album of the year, the self-titled debut by Finnish alt-rock band Ghost World, which I wrote enthusiastically about  I was hugely surprised in 2018 to find that my album of the year was an electronic one,

I was hugely surprised in 2018 to find that my album of the year was an electronic one,  In 2019, I loved another Collectress album, Different Geographies but it didn’t replace or match Mondegreen in my affections. I can’t seem to find my album of the year strangely, but it might well have been Youth in Ribbons by Revenant Marquis, still my favourite of that prolific artist’s releases.

In 2019, I loved another Collectress album, Different Geographies but it didn’t replace or match Mondegreen in my affections. I can’t seem to find my album of the year strangely, but it might well have been Youth in Ribbons by Revenant Marquis, still my favourite of that prolific artist’s releases.

A foolish name, you might think; and yet there have been no less than three different bands called Funeral Bitch. This is the first and best of the three, the one formed by Paul Speckmann in 1986-8 between different incarnations of the much better known Master. Funeral Bitch were much in the same vein; extremely fast and rough (though still anthemic) death/thrash, with Speckmann’s hoarse bellowing a bit too prominent in the thin mix. That said, the demos are imbued with a real raw vitality that could arguably have been lost with the kind of production favoured by the big-name thrash bands of the era. It’s a real time capsule of the more extreme end of the 80s thrash scene and there’s a fair amount of intentional silliness too; a key but often forgotten feature of era. Interestingly, the guitarist is Alex Olvera, better known for his tenure as bassist with mid-level speed metal band Znöwhite around the same time. Only essential for Master fans, but generally fun, even if the live tracks are (appropriately) ‘rough as guts’ as they say down under.

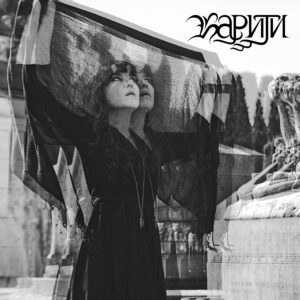

A foolish name, you might think; and yet there have been no less than three different bands called Funeral Bitch. This is the first and best of the three, the one formed by Paul Speckmann in 1986-8 between different incarnations of the much better known Master. Funeral Bitch were much in the same vein; extremely fast and rough (though still anthemic) death/thrash, with Speckmann’s hoarse bellowing a bit too prominent in the thin mix. That said, the demos are imbued with a real raw vitality that could arguably have been lost with the kind of production favoured by the big-name thrash bands of the era. It’s a real time capsule of the more extreme end of the 80s thrash scene and there’s a fair amount of intentional silliness too; a key but often forgotten feature of era. Interestingly, the guitarist is Alex Olvera, better known for his tenure as bassist with mid-level speed metal band Znöwhite around the same time. Only essential for Master fans, but generally fun, even if the live tracks are (appropriately) ‘rough as guts’ as they say down under. Kariti is a Russian-Italian singer of dark folk music and, after an extremely peculiar and archaic-sounding voices-only intro, Covered Mirrors becomes an album of moody semi-acoustic songs which are not especially folk-sounding, but are very pretty indeed. The guitar sound is crisp and almost tangible, and the vocals (mainly in English) are clear and mournful, as befits the album’s themes of ‘death and parting’. It’s a beautifully grave and austere record, with an intimate quality that (especially through headphones) brings the listener extremely close to the performance, while remaining emotionally remote and unreachable: a perfect album for a time of quarantine, if not one that will cheer anyone up.

Kariti is a Russian-Italian singer of dark folk music and, after an extremely peculiar and archaic-sounding voices-only intro, Covered Mirrors becomes an album of moody semi-acoustic songs which are not especially folk-sounding, but are very pretty indeed. The guitar sound is crisp and almost tangible, and the vocals (mainly in English) are clear and mournful, as befits the album’s themes of ‘death and parting’. It’s a beautifully grave and austere record, with an intimate quality that (especially through headphones) brings the listener extremely close to the performance, while remaining emotionally remote and unreachable: a perfect album for a time of quarantine, if not one that will cheer anyone up. Alternately really great and very silly indeed, the sci-fi theme/concept behind Space Goretex sometimes gets in the way of the music. At its best the marriage of the unusual (but mostly surprisingly low key) musical textures of

Alternately really great and very silly indeed, the sci-fi theme/concept behind Space Goretex sometimes gets in the way of the music. At its best the marriage of the unusual (but mostly surprisingly low key) musical textures of  Always a surprise to find that non-mainstream musicians still release singles, but that’s what Manes are doing; and, like their last album, the superb Slow Motion Death Sequence it’s black metal in feeling only; musically the title track is a kind of eccentric and brooding widescreen gothic rock (I guess; it reminded me a bit of the Planet Caravan type early Black Sabbath ballads and musically but definitely not vocally a little bit of Fields of the Nephilim; there’s no electronic element on this one). It’s beautifully recorded, the title track warm and limpid but with an undertone of unease that builds throughout. The B side (is that still what it is for a digital release?) is Mouth of the Volcano, an atmospheric doomy semi-electronic chug built around a strangely familiar spoken word section that can’t place and featuring Asgeir Hatlan (last heard in Manes on 2014’s Be All, End All) and some spooky Diamanda Galas-ish vocals from Anna Murphy (ex-Eluveitie) and Ana Carolina Skaret. An unsettling but very listenable pair of songs and so a single worth releasing; and with beautiful artwork too.

Always a surprise to find that non-mainstream musicians still release singles, but that’s what Manes are doing; and, like their last album, the superb Slow Motion Death Sequence it’s black metal in feeling only; musically the title track is a kind of eccentric and brooding widescreen gothic rock (I guess; it reminded me a bit of the Planet Caravan type early Black Sabbath ballads and musically but definitely not vocally a little bit of Fields of the Nephilim; there’s no electronic element on this one). It’s beautifully recorded, the title track warm and limpid but with an undertone of unease that builds throughout. The B side (is that still what it is for a digital release?) is Mouth of the Volcano, an atmospheric doomy semi-electronic chug built around a strangely familiar spoken word section that can’t place and featuring Asgeir Hatlan (last heard in Manes on 2014’s Be All, End All) and some spooky Diamanda Galas-ish vocals from Anna Murphy (ex-Eluveitie) and Ana Carolina Skaret. An unsettling but very listenable pair of songs and so a single worth releasing; and with beautiful artwork too. More solemn, downbeat but mostly very pretty music. I had never heard Midwife (the solo project of Madeline Johnston) before; on this album at least, it’s a bare, guitar-based sound with some ambient electronic elements, sort of shoegaze-y but not. The nearest comparison I can think of (not that anyone asked for one) is Codeine circa Frigid Stars. Forever was inspired by the unexpected loss of a friend and the music is as fragile and mournful as you’d expect. The sound is warm, clear and intimate-sounding – aside from the vocals, which are distanced by a strange spacey, reverb effect; perhaps for the best as the raw emotion is rendered slightly remote and universal, rather than immediate and personal. It’s clearly not an album for all moods: although the closing track S.W.I.M. speeds up to a Jesus and Mary Chain-esque plod, Forever is consistently slow and elegiac and nothing really lifts it out of its furrow of sadness: but beautiful for all that.

More solemn, downbeat but mostly very pretty music. I had never heard Midwife (the solo project of Madeline Johnston) before; on this album at least, it’s a bare, guitar-based sound with some ambient electronic elements, sort of shoegaze-y but not. The nearest comparison I can think of (not that anyone asked for one) is Codeine circa Frigid Stars. Forever was inspired by the unexpected loss of a friend and the music is as fragile and mournful as you’d expect. The sound is warm, clear and intimate-sounding – aside from the vocals, which are distanced by a strange spacey, reverb effect; perhaps for the best as the raw emotion is rendered slightly remote and universal, rather than immediate and personal. It’s clearly not an album for all moods: although the closing track S.W.I.M. speeds up to a Jesus and Mary Chain-esque plod, Forever is consistently slow and elegiac and nothing really lifts it out of its furrow of sadness: but beautiful for all that. More black metal, this time from Iceland. Pretty standard (in a good way), polished but not symphonic black metal, modern but very much influenced by the classic Scandinavian bands (maybe more the second-and-a-half wave, like Kampfar than the classic Mayhem-Darkthrone-Burzum axis) it’s all very well put together and has plenty of muscle and melody. Two things save it from just being yet more (and there is a lot of it) proficient ‘grim & frostbitten’ black metal – firstly, some strange and very Icelandic anthemic moments; I say very Icelandic only because those moments remind me a bit of some of the epic, windswept bits in Solstafir’s music. Although recommended by the label for fans of fellow Icelanders Misþyrming, Nyrst, though inhabiting more or less the same kind of sub-genre, definitely have their own sound and style. (I highly recommend Misþyrming’s

More black metal, this time from Iceland. Pretty standard (in a good way), polished but not symphonic black metal, modern but very much influenced by the classic Scandinavian bands (maybe more the second-and-a-half wave, like Kampfar than the classic Mayhem-Darkthrone-Burzum axis) it’s all very well put together and has plenty of muscle and melody. Two things save it from just being yet more (and there is a lot of it) proficient ‘grim & frostbitten’ black metal – firstly, some strange and very Icelandic anthemic moments; I say very Icelandic only because those moments remind me a bit of some of the epic, windswept bits in Solstafir’s music. Although recommended by the label for fans of fellow Icelanders Misþyrming, Nyrst, though inhabiting more or less the same kind of sub-genre, definitely have their own sound and style. (I highly recommend Misþyrming’s  And another one-woman folk project. Ols (Polish singer and multi-instrumentalist Anna Maria Oskierko) is very different from Kariti though, and Widma is a primitive, ritualistic sounding album with none of Covered Mirrors‘s accessible, almost pop sheen. Widma does sound traditional, but it’s more akin to Wardruna and the archaeological end of pagan folk music than the glossy Clannad-ish kind recently heard on the latest Myrkur album. This is, by contrast, pleasantly droning and primal (and in that respect reminds me of an album I bought via MySpace many years ago by

And another one-woman folk project. Ols (Polish singer and multi-instrumentalist Anna Maria Oskierko) is very different from Kariti though, and Widma is a primitive, ritualistic sounding album with none of Covered Mirrors‘s accessible, almost pop sheen. Widma does sound traditional, but it’s more akin to Wardruna and the archaeological end of pagan folk music than the glossy Clannad-ish kind recently heard on the latest Myrkur album. This is, by contrast, pleasantly droning and primal (and in that respect reminds me of an album I bought via MySpace many years ago by  A contrast to everything else here, Norwegian collective Weserbergland’s second album consists of one 42 minute track, but it’s not the krautrock–influenced prog of their Can/Tangerine Dream-flavoured debut. Instead, it’s a chaotic but weirdly coherent kind of collage which consists of performances on conventional-ish instruments: guitar/strings/sax/turntables, cut up, messed about with and reassembled into a kind of melancholy, cinematic symphony. The strange, unpredictable stuttering percussion seems like it should disrupt the flow of the piece, but somehow the jerkiness becomes part of the mood and it all flows perfectly, if not in a straight line. It’s really not like anything else I’ve heard, but reminds me a little of Masahiko Satoh and the Soundbreakers’ 1971 classic avant-garde jazz-prog-whatever album Amalgamation in its sheer ear-defeating unclassifiable-ness. I’m sure it won’t go down in history as such, but this may be a definitively 2020 release.

A contrast to everything else here, Norwegian collective Weserbergland’s second album consists of one 42 minute track, but it’s not the krautrock–influenced prog of their Can/Tangerine Dream-flavoured debut. Instead, it’s a chaotic but weirdly coherent kind of collage which consists of performances on conventional-ish instruments: guitar/strings/sax/turntables, cut up, messed about with and reassembled into a kind of melancholy, cinematic symphony. The strange, unpredictable stuttering percussion seems like it should disrupt the flow of the piece, but somehow the jerkiness becomes part of the mood and it all flows perfectly, if not in a straight line. It’s really not like anything else I’ve heard, but reminds me a little of Masahiko Satoh and the Soundbreakers’ 1971 classic avant-garde jazz-prog-whatever album Amalgamation in its sheer ear-defeating unclassifiable-ness. I’m sure it won’t go down in history as such, but this may be a definitively 2020 release.

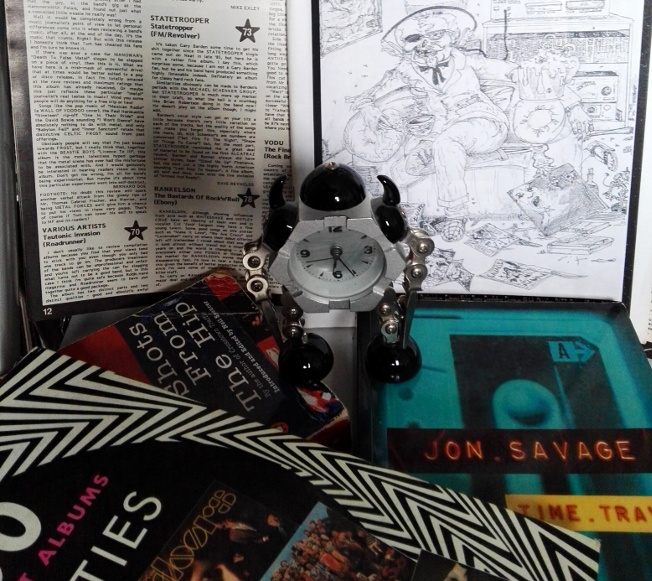

I just finished reading the newest edition* of Jon Savage’s brilliant England’s Dreaming which is as good as any music-related book I’ve ever read and made me realise how many parallels there are between now and the political situation in mid-70s Britain. Up to a point, that is. It would be hard, even I think for a conservative person, to see the victory of Johnson’s Tories as a return to some kind of sensible order in the way that deluded right wingers saw Thatcher’s victory – which did, it has to be said, render somewhat pointless the extreme right wing groups like the National Front & British Movement that had been growing in strength and influence throughout the decade. As with Johnson/the ERG and their wooing of the UKIP/nazi fanbase though, the reassurance that comes from seeing extremist groups losing popularity is soured (to put it mildly) by having people in charge who appeal to that demographic.

I just finished reading the newest edition* of Jon Savage’s brilliant England’s Dreaming which is as good as any music-related book I’ve ever read and made me realise how many parallels there are between now and the political situation in mid-70s Britain. Up to a point, that is. It would be hard, even I think for a conservative person, to see the victory of Johnson’s Tories as a return to some kind of sensible order in the way that deluded right wingers saw Thatcher’s victory – which did, it has to be said, render somewhat pointless the extreme right wing groups like the National Front & British Movement that had been growing in strength and influence throughout the decade. As with Johnson/the ERG and their wooing of the UKIP/nazi fanbase though, the reassurance that comes from seeing extremist groups losing popularity is soured (to put it mildly) by having people in charge who appeal to that demographic. Sounding something like The Birthday Party playing noisy free jazz, the Massaker are a brutal guitar-bass-drums (with minimalist vocals) trio; heavy on feedback, tense dynamics and churning distortion, but sometimes almost groovy and (very) occasionally kind of pretty. Home was their fifth album and it’s pretty similar to the only other one of their albums that I know, The Tribe, from 1987. Squally, angular and dark but with insistent percussion, it’s a great palate-cleanser for your ears after too much pop music.

Sounding something like The Birthday Party playing noisy free jazz, the Massaker are a brutal guitar-bass-drums (with minimalist vocals) trio; heavy on feedback, tense dynamics and churning distortion, but sometimes almost groovy and (very) occasionally kind of pretty. Home was their fifth album and it’s pretty similar to the only other one of their albums that I know, The Tribe, from 1987. Squally, angular and dark but with insistent percussion, it’s a great palate-cleanser for your ears after too much pop music.

This Austrian black metal project has a very specific local (Tyrolean) focus, but judging by its Facebook page is the brainchild of Italian ex-pat Fabio D’Amore of symphonic power metal band Serenity; which makes sense – for all its atmospheric/folkish elements (there are some very nice jangly clean parts), this is a theatrical, musicianly album which feels epic and polished rather than dark and brutal. The band’s name refers to a pagan goddess, and throughout the album an odd, witchy narrator pops up declaiming or whispering, who I assume is the woman in the artwork, who the promotional material refers to as “the front woman [who] will sermonize, face-painted in historical black garb with embroidered belt and cast-iron broom …”

This Austrian black metal project has a very specific local (Tyrolean) focus, but judging by its Facebook page is the brainchild of Italian ex-pat Fabio D’Amore of symphonic power metal band Serenity; which makes sense – for all its atmospheric/folkish elements (there are some very nice jangly clean parts), this is a theatrical, musicianly album which feels epic and polished rather than dark and brutal. The band’s name refers to a pagan goddess, and throughout the album an odd, witchy narrator pops up declaiming or whispering, who I assume is the woman in the artwork, who the promotional material refers to as “the front woman [who] will sermonize, face-painted in historical black garb with embroidered belt and cast-iron broom …”