But superstition, like belief, must die,

And what remains when disbelief has gone?

Grass, weedy pavement, brambles, buttress, sky,

A shape less recognisable each week,

A purpose more obscure.

Philip Larkin, Church Going (1954)

Given that Christianity seemed to be – in the sense of being a kind of shared societal glue – on its way out in the 1950s, and was undermined further by the social revolutions of the 1960s and 70s, it’s surprising in a way that churches are still standing at all. But what Larkin, for all of his humanist cynicism didn’t foresee, is what seems the obvious fate of churches in the 21st century: they won’t be allowed to peacefully moulder into dust and neglect like the menhirs and cairns of previous eras – they get sold instead.

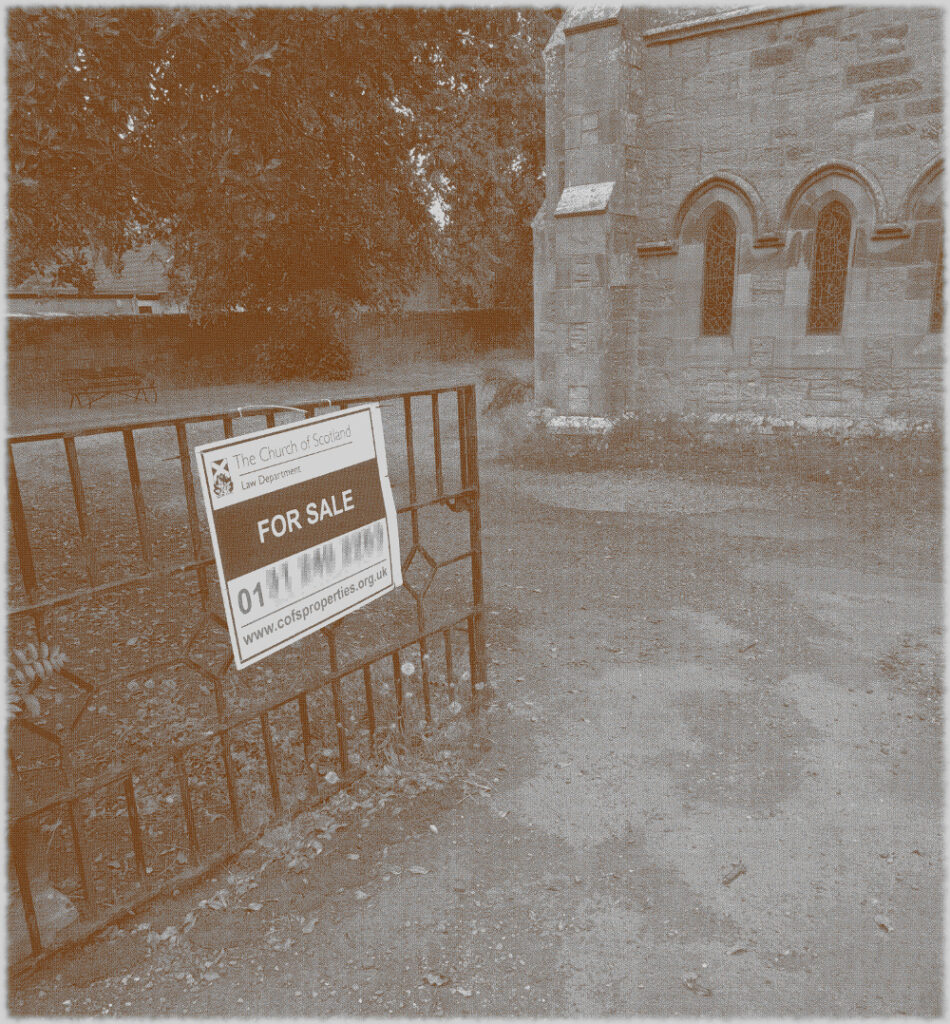

At the time of writing, the Church of Scotland has seventeen churches for sale, among other kinds of properties and plots of land. The same thing isn’t happening with Catholic churches, Mosques, Synagogues or Mormon temples or whatever it is that Scientologists have – not because of anything inherently superior about those religions or the quality of their followers’ faith, but because, at the time when these churches were built – mostly in the 19th century, but some even earlier – the Church of Scotland was something you had to opt out of, not something you had to join. And therefore, in a way – although not of course a legally binding way – the Church of Scotland is selling off something which belongs to the people of Scotland.

The idea that money is more important to the Church of Scotland than the buildings that were at the centre of the spiritual and social lives of generations of people (and also, the place that God lived, I guess) seems grotesque, but there it is. It’s just bricks (or stone) and mortar, after all; or that, presumably is the logic, because God doesn’t actually live in a stone building but in either heaven or the hearts of believers etc, etc. And yet, if it’s just a building, how come people can only vandalise houses or schools or barns, but they can “desecrate” churches? “De-consecration” – what the church does in order to render its buildings saleable – is just a non-inflammatory way of saying desecration. De-consecrating the church doesn’t affect the material of the building, but it does remove its purpose – but what it can’t do is remove its history. So if you buy a church, what is it that are you actually buying? In a book I liked as a teenager, Terry Brooks’s Magic Kingdom For Sale – Sold! (1986), a depressed lawyer called Ben Holiday buys what turns out to be something like Narnia or Middle Earth, from a catalogue (nowadays it would be from a website). If Mr Holiday bought a church, he wouldn’t be mystically transported to an otherworldly realm, but he would – and the buyers of these buildings do – become the owner of a place where thousands of people were, in a meaningful way, transported to a place where, whatever the privations and terrors of their daily lives might be, things made some sort of black-and-white sense. Somewhere that virtue was rewarded with eternal paradise, vice was punished with eternal damnation and the person in the pulpit had the correct answers to whatever questions life was throwing at you. You don’t have to believe in any of that to realise that it was (and to some extent I suppose still is) important.

The idea that money is more important to the Church of Scotland than the buildings that were at the centre of the spiritual and social lives of generations of people (and also, the place that God lived, I guess) seems grotesque, but there it is. It’s just bricks (or stone) and mortar, after all; or that, presumably is the logic, because God doesn’t actually live in a stone building but in either heaven or the hearts of believers etc, etc. And yet, if it’s just a building, how come people can only vandalise houses or schools or barns, but they can “desecrate” churches? “De-consecration” – what the church does in order to render its buildings saleable – is just a non-inflammatory way of saying desecration. De-consecrating the church doesn’t affect the material of the building, but it does remove its purpose – but what it can’t do is remove its history. So if you buy a church, what is it that are you actually buying? In a book I liked as a teenager, Terry Brooks’s Magic Kingdom For Sale – Sold! (1986), a depressed lawyer called Ben Holiday buys what turns out to be something like Narnia or Middle Earth, from a catalogue (nowadays it would be from a website). If Mr Holiday bought a church, he wouldn’t be mystically transported to an otherworldly realm, but he would – and the buyers of these buildings do – become the owner of a place where thousands of people were, in a meaningful way, transported to a place where, whatever the privations and terrors of their daily lives might be, things made some sort of black-and-white sense. Somewhere that virtue was rewarded with eternal paradise, vice was punished with eternal damnation and the person in the pulpit had the correct answers to whatever questions life was throwing at you. You don’t have to believe in any of that to realise that it was (and to some extent I suppose still is) important.

Like, I’m sure, many convinced lifelong atheists (and I’m a very un-spiritual one at that), I love churches. The architecture, the fixtures and fittings, the solemn atmosphere. The idea of building on top of (Native American) Indian burial grounds was enough to fuel horror fiction and urban legend for a century; will turning churches into houses, flats and offices do something similar? Probably not; although some of the churches for sale do indeed still have graveyards attached, the churches themselves, whether used or not, are utterly familiar to the local people. Like the Indian burial grounds, they have, for these people, always been there, but unlike them, they have always been visible, and have far more mundane connotations. They aren’t, or weren’t just the places people got married or had funeral services, they are places where, very recently, a few times a year you trooped along with your primary school classmates to hear about the less commercial, less fun aspects of Easter or Christmas and to sing a few hymns. In short, even now churches aren’t, or are rarely “other” in the way that (to non-indigenous settlers and their descendants) Indian burial grounds are. But, after generations will they still be familiar in that way, or will they become just funny-shaped houses? Who knows, but it’s sad to think so.

Like, I’m sure, many convinced lifelong atheists (and I’m a very un-spiritual one at that), I love churches. The architecture, the fixtures and fittings, the solemn atmosphere. The idea of building on top of (Native American) Indian burial grounds was enough to fuel horror fiction and urban legend for a century; will turning churches into houses, flats and offices do something similar? Probably not; although some of the churches for sale do indeed still have graveyards attached, the churches themselves, whether used or not, are utterly familiar to the local people. Like the Indian burial grounds, they have, for these people, always been there, but unlike them, they have always been visible, and have far more mundane connotations. They aren’t, or weren’t just the places people got married or had funeral services, they are places where, very recently, a few times a year you trooped along with your primary school classmates to hear about the less commercial, less fun aspects of Easter or Christmas and to sing a few hymns. In short, even now churches aren’t, or are rarely “other” in the way that (to non-indigenous settlers and their descendants) Indian burial grounds are. But, after generations will they still be familiar in that way, or will they become just funny-shaped houses? Who knows, but it’s sad to think so.

However much one does or doesn’t believe in the mythology that put them there, churches, just as local landmarks, bear the weight of memory, just as schools, war memorials, statues and monuments do. Although a valuable and significant thing, it’s a personal, private and unknowable kind of value; nostalgia, in its original, Greek meaning of ‘homecoming pain’ can be evoked in all of its intense complexity by almost anything, and in your own private iconography a road sign or piece of weed-strewn wasteland is likely to be as potent as, or even more potent than the more obvious celestial symbolism of the heaven-pointed steeple and arched windows. But the fact remains that the hopes, beliefs, dreams, grief and pain of generations was directed towards the church like lightning towards the weather vane that surmounts it; there is a kind of power just in that.

So what should be done with churches? You can’t keep everything forever, after all, and the Church of Scotland is, strange though it is to say it, a business. The people used to belong to it; it never belonged to the people and its churches are not public property in anything but the spiritual sense. But perhaps they should be: granted, they only reflect one strand of what is now a multicultural (and what was always a multi-faith) nation, but it’s a strand that informs attitudes and ways of life that contribute, both negatively and positively to the character of the country and its culture to this day. And although I don’t personally believe in the idea that buildings and land absorb a kind of psychic residue that manifests itself in the ghosts, hauntings and folklore beloved of digital TV channels, I feel like they should.

Those fundamental life events; christenings, marriages, funerals, wars, disasters – all of those lost people and all of that vanished emotion, should have some kind of monument or repository – and what better place than a church? Still; maintaining empty buildings purely for the sake of their history is an expensive, ethically dubious business and hardly an indicator of cultural good health. Finding new uses for these kinds of buildings that somehow respects their history is no easy task either. Personally, I’d like the government to buy them and use them to display the large percentage of publicly owned art that is currently languishing in the storerooms of galleries and museums, fulfilling in some ways at least, the National Galleries of Scotland’s strategic plan: “we will make the national collection accessible to all and inspire curiosity across the world. We want to connect with our audiences and with each other in new, collaborative and involving ways.” It would be appropriate in a way; human beings create art as god is supposed to have created people after all, and people with or without gods make art; it expresses many of the same fundamental impulses and emotions as religion. But it’s hardly an idea that’s likely to capture the public imagination, except in the negative sense that ambitious government spending on the arts – not that there has been much of that – always invites manufactured outrage. Ah well, it’s probably best to just make them into flats.

* I realise the double meaning was already implied in the title of Larkin’s poem, but why not render it completely unsubtle with a comma?