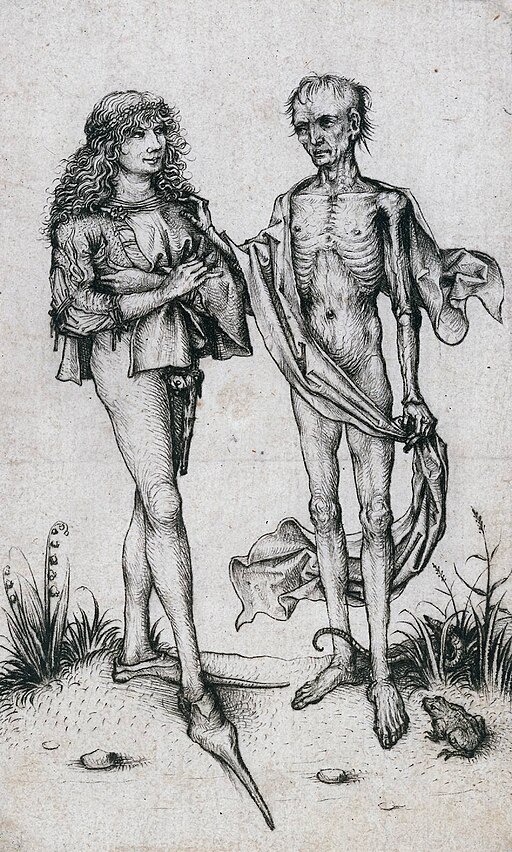

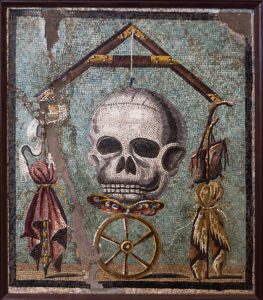

With apologies to Marcel Proust – but not very vehement apologies, because it’s true – the taste of honey on toast is as powerfully evocative and intensely transporting to me as anything that I can think of. The lips and tongue that made that association happen don’t exist anymore and neither does the face, neither do the eyes, and neither does one of the two brains and/or hearts* that I suppose really made it happen (mine are still there, though). In 21st century Britain, it’s more likely than not that even her bones don’t exist anymore, which makes the traditional preoccupation with returning to dust feel apt and more immediate and (thankfully?) reduces the kind of corpse-fetishising morbidity that seems to have appealed so much to playgoers in the Elizabethan/Jacobean era.

Thou shell of death,

Once the bright face of my betrothed lady,

When life and beauty naturally fill’d out

These ragged imperfections,

When two heaven-pointed diamonds were set

In those unsightly rings: then ’twas a face

So far beyond the artificial shine

Of any woman’s bought complexion

(The Revenger’s Tragedy (1606/7) by Thomas Middleton and/or Cyril Tourneur, Act one, Scene one)

*is the heart in the brain? In one sense obviously not, in another maybe, but the sensations associated with the heart seem often to happen somewhere around the stomach; or is that just me?

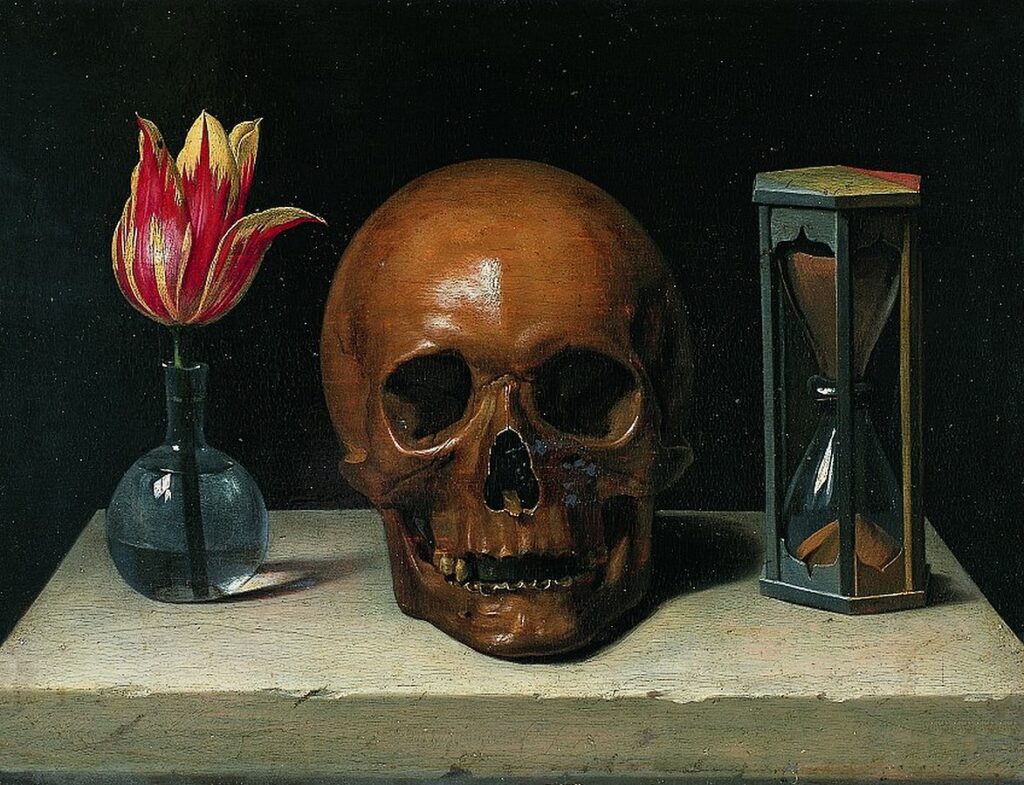

More to the point, “here hung those lips that I have kissed I know not how oft“, etc. All of which is beautiful; but for better or worse, a pile of ash isn’t likely to engender the same kind of thoughts or words as Yorick’s – or anybody’s – skull. But anyway, the non-existence of a person – or, even more abstractly, the non-existence of skin that has touched your skin (though technically of course all of the skin involved in those kisses has long since disappeared into dust and been replaced anyway) is an absence that’s strange and dismal to think about. But then most things don’t exist.

But honey does exist of course; and the association between human beings and sugary bee vomit goes back probably as long as human beings themselves. There are Mesolithic cave paintings, 8000 years old or more, made by people who don’t exist, depicting people who may never have existed except as drawings, or may have once existed but don’t anymore, plundering beehives for honey. Honey was used by the ancient Egyptians, who no longer exist, in some of their most solemn rites, it had sacred significance for the ancient Greeks, who no longer exist, it was used in medicine in India and China, which do exist now but technically didn’t then, by people who don’t, now. Mohammed recommended it for its healing properties; it’s a symbol of abundance in the Bible and it’s special enough to be kosher despite being the product of unclean insects. It’s one of the five elixirs of Hinduism, Buddha was brought honey by a monkey that no longer exists. The Vikings ate it and used it for medicine too. Honey was the basis of mead, the drink of the Celts who sometimes referred to the island of Britain as the Isle of Honey.

And so on and on, into modern times. But also (those Elizabethan-Jacobeans again) “The sweetest honey is loathsome in its own deliciousness. And in the taste destroys the appetite.” (William Shakespeare, Romeo and Juliet (c.1595) Act 2, scene 6) “Your comfortable words are like honey. They relish well in your mouth that’s whole; but in mine that’s wounded they go down as if the sting of the bee were in them.”(John Webster, The White Devil (1612), Act 3. Sc.ene 3). See also “honey trap”. “Man produces evil as a bee produces honey.”You catch more flies with honey.

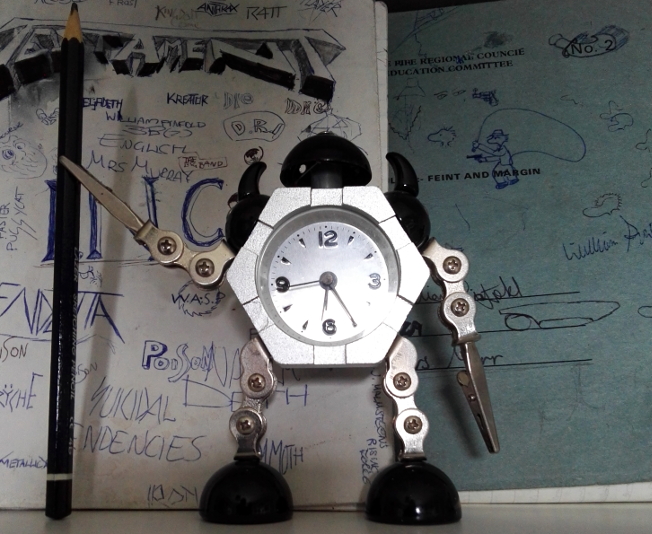

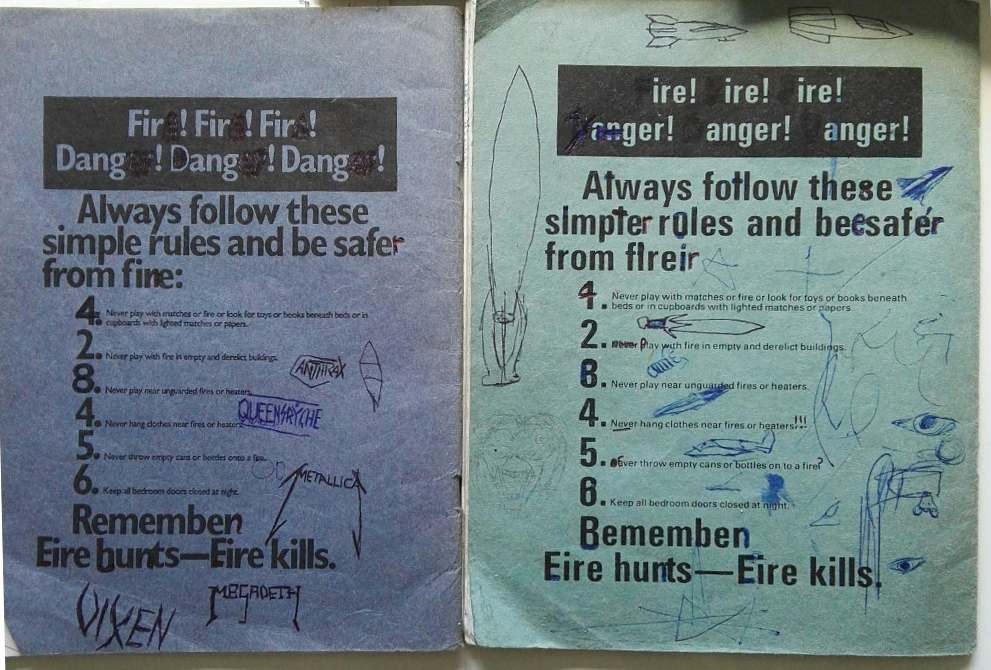

But on the whole, the sweetness of honey is not and has never been sinister. A Taste of Honey, Tupelo Honey, “Wild Honey,” “Honey Pie”, “Just like Honey,” “Me in Honey,” “Put some sugar on it honey,” Pablo Honey, “Honey I Sure Miss You.” Honey to the B. “Honey” is one of the sweetest (yep) of endearments that people use with each other. Winnie-the-Pooh and Bamse covet it. Honey and toast tasted in a kiss at the age of 14 is, in the history of the world, a tiny and trivial thing, but it’s enough to resonate throughout a life, just as honey has resonated through the world’s human cultures. Honey’s Dead. But the mouth that tasted so sweetly of honey doesn’t exist anymore. Which is sad, because loss is sad. But how sad? Most things never exist and even most things that have existed don’t exist now, so maybe the fact that it has existed is enough.

“Most things don’t exist” seems patently untrue: for a thing to be ‘a thing’ it must have some kind of existence, surely? And yet, even leaving aside things and people that no longer exist, we are vastly outnumbered by the things that have never existed, from the profound to the trivial. Profound, well even avoiding offending people and their beliefs, probably few people would now say that Zeus and his extended family are really living in a real Olympus. Trivially, 70-plus years on from the great age of the automobile, flying cars as imagined by generations of children, as depicted in books and films, are still stubbornly absent from the skies above our roads. The idea of them exists, but even if – headache-inducing notion – it exists as a specific idea (“the idea of a flying car”), rather than just within the general realm of “ideas,” an idea is an idea, a thing perhaps but not the thing that it is about. Is a specific person’s memory of another person a particular thing because it relates to a particular person, or does it exist only under the larger and more various banner of “memories”? Either way, it’s immaterial, because even though the human imagination is a thing that definitely exists, the idea of a flying car is no more a flying car than Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing of a flying machine was a flying machine or that my memory of honey-and-toast kisses is a honey-and-toast kiss.

If you or I picture a human being with electric blue skin, we can imagine it and if we have the talent we can draw it, someone could depict it in a film, but it wouldn’t be the thing itself, because human beings with electric blue skin, like space dolphins, personal teleportation devices, seas of blood, winged horses, articulate sentient faeces and successful alchemical experiments, don’t exist. And depending on the range of your imagination (looking at that list mine seems a bit limited), you could think of infinite numbers of things that don’t exist. There are also, presumably, untold numbers of things that do exist but that we personally don’t know about or that we as a species don’t know about yet. But even if it was possible to make a complete list of all of the things in existence (or things in existence to date; new things are invented or develop or evolve all the time), it would always be possible to think of even more things that don’t exist, – simply, in the least imaginative way, by naming variations on, or parodies of everything that does exist. So supermassive black holes exist? Okay, but what about supertiny pink holes? What about supermedium beige holes? This June, a new snake (disappointingly named Ovophis jenkinsi) was discovered. But what about a version of Ovophis jenkinsi that sings in Spanish or has paper bones or smells like Madonna? They don’t exist.

Kind of a creepy segue if you think about it (so please don’t), but like those beautifully-shaped lips that tasted of honey, my mother no longer exists, except as a memory, or lots of different memories, belonging to lots of different people. Presumably she exists in lots of memories as lots of different people who happen to have the same name. But unlike supermedium beige holes, the non-existence of previously-existing things and people is complex, because of the different perspectives they are remembered from. But regardless, they are still fundamentally not things anymore. But even with the ever-growing, almost-infinite number of things, there are, demonstrably, more things that don’t exist. And, without wishing to be horribly negative or repeating things I’ve written before, one of the surprises with the death of a close relative was to find that death does exist. Well, obviously, everyone knows that – but not just as an ending or as the absence of life, as was always known, but as an active, grim-reaper-like force of its own. For me, the evidence for that – which I’m sure could be explained scientifically by a medical professional – is the cold that I mentioned in the previous article. Holding a hand that gets cold seems pretty normal; warmth ebbing away as life ebb away; that’s logical and natural. But this wasn’t the expected (to me) cooling down of a warm thing to room temperature, like the un-drunk cups of tea which day after day were brought and cooled down because the person they were brought for didn’t really want them anymore, just the idea of them. That cooling felt natural, as did the warming of the glass of water that sat un-drunk at the bedside because the person it was for could no longer hold or see it. That water had been cold but had warmed up to room temperature, but the cold in the hand wasn’t just a settling in line with ambient conditions. It was active cold; hands chilling and then radiating cold in quite an intense way, a coldness that dropped far below room temperature. I mentioned it to a doctor during a brief, unbelievably welcome break to get some air, and she said “Yes, she doesn’t have long left.” Within a few days I wished I’d asked for an explanation of where that cold was coming from; where is it generated? Which organ in the human body can generate cold so quickly and intensely? Does it do it in any other situations? And if not, why not? So, although death can seem abstract, in the same sense that ‘life’ seems abstract, being big and pervasive, death definitely exists. But as what? Don’t know; not a single entity, since it’s incipient in everyone, coded into our DNA: but that coding has nothing to do with getting hit by cars or drowning or being shot, does it? So, a big question mark to that. Keats would say not to question it, just to enjoy the mystery. Well alright then.

But since most things *don’t* exist, but death definitely does exist, existence is, in universal terms, rare enough to be something like winning the lottery. But like winning the lottery, existence in itself is not any kind of guarantee of happiness or satisfaction or even honey-and-toast kisses; but it at least offers the possibility of those things, whereas non-existence doesn’t offer anything, not even peace, which has to be experienced to exist. We have all not existed before and we will all not exist again; but honey will still be here, for as long as bees are at least. I don’t know if that’s comforting or not. But if you’re reading this – and I’m definitely writing it – we do currently exist, so try enjoy your lottery win, innit.

Something silly about music next time I think.

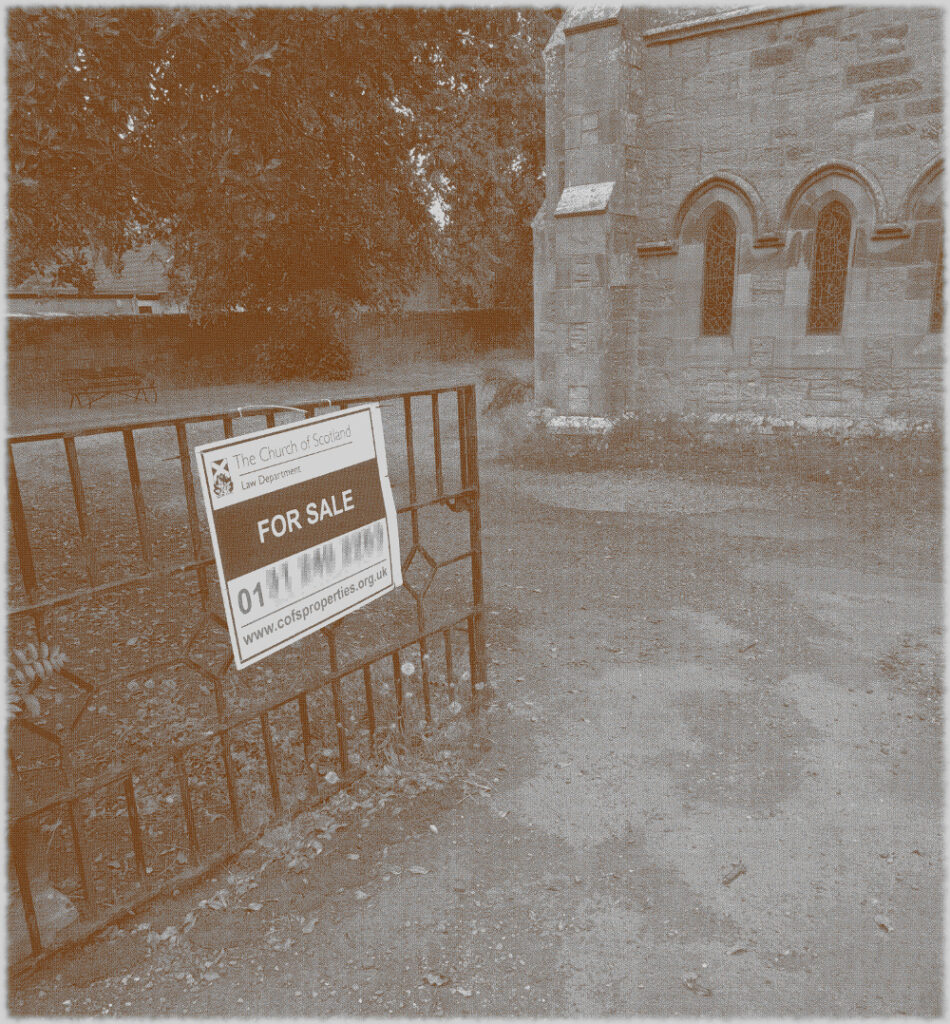

The idea that money is more important to the Church of Scotland than the buildings that were at the centre of the spiritual and social lives of generations of people (and also, the place that God lived, I guess) seems grotesque, but there it is. It’s just bricks (or stone) and mortar, after all; or that, presumably is the logic, because God doesn’t actually live in a stone building but in either heaven or the hearts of believers etc, etc. And yet, if it’s just a building, how come people can only vandalise houses or schools or barns, but they can “desecrate” churches? “De-consecration” – what the church does in order to render its buildings saleable – is just a non-inflammatory way of saying desecration. De-consecrating the church doesn’t affect the material of the building, but it does remove its purpose – but what it can’t do is remove its history. So if you buy a church, what is it that are you actually buying? In a book I liked as a teenager, Terry Brooks’s Magic Kingdom For Sale – Sold! (1986), a depressed lawyer called Ben Holiday buys what turns out to be something like Narnia or Middle Earth, from a catalogue (nowadays it would be from a website). If Mr Holiday bought a church, he wouldn’t be mystically transported to an otherworldly realm, but he would – and the buyers of these buildings do – become the owner of a place where thousands of people were, in a meaningful way, transported to a place where, whatever the privations and terrors of their daily lives might be, things made some sort of black-and-white sense. Somewhere that virtue was rewarded with eternal paradise, vice was punished with eternal damnation and the person in the pulpit had the correct answers to whatever questions life was throwing at you. You don’t have to believe in any of that to realise that it was (and to some extent I suppose still is) important.

The idea that money is more important to the Church of Scotland than the buildings that were at the centre of the spiritual and social lives of generations of people (and also, the place that God lived, I guess) seems grotesque, but there it is. It’s just bricks (or stone) and mortar, after all; or that, presumably is the logic, because God doesn’t actually live in a stone building but in either heaven or the hearts of believers etc, etc. And yet, if it’s just a building, how come people can only vandalise houses or schools or barns, but they can “desecrate” churches? “De-consecration” – what the church does in order to render its buildings saleable – is just a non-inflammatory way of saying desecration. De-consecrating the church doesn’t affect the material of the building, but it does remove its purpose – but what it can’t do is remove its history. So if you buy a church, what is it that are you actually buying? In a book I liked as a teenager, Terry Brooks’s Magic Kingdom For Sale – Sold! (1986), a depressed lawyer called Ben Holiday buys what turns out to be something like Narnia or Middle Earth, from a catalogue (nowadays it would be from a website). If Mr Holiday bought a church, he wouldn’t be mystically transported to an otherworldly realm, but he would – and the buyers of these buildings do – become the owner of a place where thousands of people were, in a meaningful way, transported to a place where, whatever the privations and terrors of their daily lives might be, things made some sort of black-and-white sense. Somewhere that virtue was rewarded with eternal paradise, vice was punished with eternal damnation and the person in the pulpit had the correct answers to whatever questions life was throwing at you. You don’t have to believe in any of that to realise that it was (and to some extent I suppose still is) important. Like, I’m sure, many convinced lifelong atheists (and I’m a very un-spiritual one at that), I love churches. The architecture, the fixtures and fittings, the solemn atmosphere. The idea of building on top of (Native American) Indian burial grounds was enough to fuel horror fiction and urban legend for a century; will turning churches into houses, flats and offices do something similar? Probably not; although some of the churches for sale do indeed still have graveyards attached, the churches themselves, whether used or not, are utterly familiar to the local people. Like the Indian burial grounds, they have, for these people, always been there, but unlike them, they have always been visible, and have far more mundane connotations. They aren’t, or weren’t just the places people got married or had funeral services, they are places where, very recently, a few times a year you trooped along with your primary school classmates to hear about the less commercial, less fun aspects of Easter or Christmas and to sing a few hymns. In short, even now churches aren’t, or are rarely “other” in the way that (to non-indigenous settlers and their descendants) Indian burial grounds are. But, after generations will they still be familiar in that way, or will they become just funny-shaped houses? Who knows, but it’s sad to think so.

Like, I’m sure, many convinced lifelong atheists (and I’m a very un-spiritual one at that), I love churches. The architecture, the fixtures and fittings, the solemn atmosphere. The idea of building on top of (Native American) Indian burial grounds was enough to fuel horror fiction and urban legend for a century; will turning churches into houses, flats and offices do something similar? Probably not; although some of the churches for sale do indeed still have graveyards attached, the churches themselves, whether used or not, are utterly familiar to the local people. Like the Indian burial grounds, they have, for these people, always been there, but unlike them, they have always been visible, and have far more mundane connotations. They aren’t, or weren’t just the places people got married or had funeral services, they are places where, very recently, a few times a year you trooped along with your primary school classmates to hear about the less commercial, less fun aspects of Easter or Christmas and to sing a few hymns. In short, even now churches aren’t, or are rarely “other” in the way that (to non-indigenous settlers and their descendants) Indian burial grounds are. But, after generations will they still be familiar in that way, or will they become just funny-shaped houses? Who knows, but it’s sad to think so.

Looking at the scenery, the wildlife, the roads, you have to wonder; why would anyone not care about this? I don’t mean the Howe of Fife, or Fife, or Scotland, or Britain, or Europe, or the world (although those too); just wherever you happen to be; place. Landscapes should and must change, as we change; not just the geometries and geographies we impose on them, like the furrows and plastic (though it would be nice to do away with the plastic itself), but everything. 500 years ago the Howe of Fife was covered in forest and the monarchs of Scotland hunted wild boar here. A thousand years ago, a Scotland that was different in shape, size and culture was being ruled by Alexander I, then near the end of his life, having recently lost his wife Sybilla of Normandy, the French child of Henry I of England; Alexander would be succeeded by his brother David, then Prince of the Cumbrians; by James’s time all of these details would seem strange. Two thousand years ago, the Howe of Fife was part of southern Caledonia, that is the land to the north of the river Forth; at least the Romans, still fifty years from their attempted conquest, called it Caledonia, whether the inhabitants of Caledonia had any name for the landmass in general, as opposed to their own local chiefdoms, isn’t recorded.

Looking at the scenery, the wildlife, the roads, you have to wonder; why would anyone not care about this? I don’t mean the Howe of Fife, or Fife, or Scotland, or Britain, or Europe, or the world (although those too); just wherever you happen to be; place. Landscapes should and must change, as we change; not just the geometries and geographies we impose on them, like the furrows and plastic (though it would be nice to do away with the plastic itself), but everything. 500 years ago the Howe of Fife was covered in forest and the monarchs of Scotland hunted wild boar here. A thousand years ago, a Scotland that was different in shape, size and culture was being ruled by Alexander I, then near the end of his life, having recently lost his wife Sybilla of Normandy, the French child of Henry I of England; Alexander would be succeeded by his brother David, then Prince of the Cumbrians; by James’s time all of these details would seem strange. Two thousand years ago, the Howe of Fife was part of southern Caledonia, that is the land to the north of the river Forth; at least the Romans, still fifty years from their attempted conquest, called it Caledonia, whether the inhabitants of Caledonia had any name for the landmass in general, as opposed to their own local chiefdoms, isn’t recorded. These back roads are quiet, but although nature is everywhere, it’s deceptive, hardly a natural landscape at all. It has been shaped by generations of human beings, by agriculture and the politics of land ownership, no less in King James’s day, when forests belonged to the King and had their own laws, than now. It reminds me both of my childhood love of Tolkien and of a line from The Fellowship of the Ring; where Bilbo says “I want to see the wild country again before I die, and the Mountains; but he [Frodo] is still in love with the Shire, with woods and fields and little rivers.” Tolkien loved both the wilderness and the smaller, more familiar (Oxfordshire-like) scenery of the Shire, but in his landscapes change is almost always bad; both on the larger scale of the desolation that evil brings to Mordor and the fiery chasms opened in the earth when the Dwarves delve ‘too deep’, and on the local level where the Shire is ruined by the arrival of industry. Michael Moorcock writes perceptively in his I think overly scathing (“The Lord of the Rings is a pernicious confirmation of the values of a morally bankrupt middle-class“

These back roads are quiet, but although nature is everywhere, it’s deceptive, hardly a natural landscape at all. It has been shaped by generations of human beings, by agriculture and the politics of land ownership, no less in King James’s day, when forests belonged to the King and had their own laws, than now. It reminds me both of my childhood love of Tolkien and of a line from The Fellowship of the Ring; where Bilbo says “I want to see the wild country again before I die, and the Mountains; but he [Frodo] is still in love with the Shire, with woods and fields and little rivers.” Tolkien loved both the wilderness and the smaller, more familiar (Oxfordshire-like) scenery of the Shire, but in his landscapes change is almost always bad; both on the larger scale of the desolation that evil brings to Mordor and the fiery chasms opened in the earth when the Dwarves delve ‘too deep’, and on the local level where the Shire is ruined by the arrival of industry. Michael Moorcock writes perceptively in his I think overly scathing (“The Lord of the Rings is a pernicious confirmation of the values of a morally bankrupt middle-class“