Faith A. Pennick

D’Angelo’s Voodoo

33⅓ books

This review may not be fair to writer/filmmaker Faith A. Pennick and her excellent book, not because I didn’t like it – it’s great – but because since I was sent the book (by now onsale), events that don’t need mentioning here have overtaken it a bit. On the plus side, probably more people have more time to read and listen to music than they have in living memory, so maybe it’s not all bad. And Pennick’s book, among other things, is an extended argument for really listening to an album as opposed to just letting it play while you do other things.

If you read my review of Glenn Hendler’s Diamond Dogs book you will probably have realised that I have quite a lot to say about Bowie (and in fact one of the few moments of pride in my writing career such as it is, is that I got to write an obituary for Bowie in an actual print magazine – and that, on reading it now I still agree with myself – which is not always the case!), whereas with D’Angelo’s Voodoo, the opposite is true; Hendler was adding to my knowledge of an artist I love, Pennick is telling me about someone who I previously knew almost nothing about. As I mentioned in that previous review, as a music journalist people are never shy about telling you what they essentially want is the music not the writing; but for me, most good writing has an element of Thomas Hardy’s dictum about poetry: “The ultimate aim of the poet should be to touch our hearts by showing his own” and in the case of the music writer that means engaging you (or rather me) whether or not one has an interest in the music itself. Here Pennick scores very highly; the narrative of how she came to know and love Voodoo manages to remain direct and personal while also bringing in all of the cultural/historical and musical context necessary to be more than a kind of diary entry.

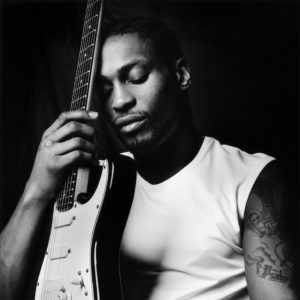

I came to the book thinking that I didn’t know anything by D’Angelo at all*, and while setting the scene, Pennick invokes a list of artists that is – to my taste in music – both encouraging (Erykah Badu, De La Soul, Angie Stone) and, though admittedly important, offputting (Michael Jackson, Lauryn Hill). But as it turns out, the fact that I didn’t know D’Angelo’s ‘greatest hits’ is not all that surprising; a key point in Pennick’s book is about how D’Angelo’s career was defined, for better or worse, by the video for Untitled (2000) – but that single didn’t chart in the UK and if I was aware of him via osmosis at all, it would have been from the trio of singles from his previous album Brown Sugar, that made the Top 40 here five years earlier.

*in fact, I should have known that his vocals (and sometimes his musicianship) appear on records by people like Q-Tip and The Roots that are more my cup of tea than his own music.

But by 2000, even if Untitled had been a hit here, the chances are I would never have seen that video. Like many people of my generation, I had a pretty good grip on what was in the top 40, whether I liked it or not (and usually I liked it not), up until the mid-90s, when Top of the Pops (TOTP), the UK’s Top 40 music TV show, was moved from its classic Thursday night slot to a Friday. This may seem a little thing, but for background, during my childhood there were only 4 (and pre-1982 only three) TV channels, which meant that, if a family watched TV at all, there was a pretty good chance that they were watching the same things as you were; and most people I knew watched TOTP – so all through school, what was at number one was common knowledge (to be fair it probably still is for school age kids). By the mid 90s (actually, any time after one’s own taste had formed), watching the show was largely a kind of empty ritual or habit but still; it did give, pre social media, a general sense of where pop music and pop culture were at at any given time.

In 2000, when Voodoo was released (I am surprised now to find that TOTP was still on at that time, albeit not in the classic slot and beginning its slow decline that ended in cancellation in 2006), aside from odd bits of experimental hip hop heard through my brother, like Kid Koala’s Carpal Tunnel Syndrome, classics like The Wu-Tang Clan’s The W and occasional forays into UK indie like Badly Drawn Boy, I was rarely listening to any music recorded after around 1975; Bowie, Funkadelic, Lou Reed, John Cale, early 70s funk, old blues and early Black Sabbath were [probably what I listened to the most. So D’Angelo passed me by; not that I think I would have liked Voodoo much at that time anyway.

But Faith A. Pennick is persuasive; I listened to Voodoo. And she is not wrong; despite lyrics that veer from great to obnoxious (just a personal preference, but I don’t think I’ve ever heard a song I liked for more than one listen whose theme is how great the performer of that song is), the album is meticulously put together, perfectly played with skill and heart – and to my surprise, with a beautifully organic sound – and in the end the only thing that puts me off of it – while in no way reducing its stature – is D’Angelo’s voice(s). It’s not that he isn’t a great singer, he clearly, demonstrably is; but the album coincides with/crystalises that period when R’n’B vocals tended to consist of multi-layered murmuring and crooning. I didn’t really like it then and it’s still not for me now – although the immediate and noticeable lack of autotune is incredibly refreshing. I used to love robot voices as a kid, but now that the slight whine of autotuned vocals is ubiquitous whenever you turn on the radio, it’s nice to hear someone who can sing, singing. In fact, for me, if you pared the vocals on Voodoo down to one main, direct voice and gave it the clarity of the drums and bass, I’d like the album a lot more; but it wouldn’t be the same album, and that’s my deficiency, not Voodoo’s.

For me, the main strength of D’Angelo’s Voodoo (the book) is in the way that Pennick weaves her own personal relationship with album and artist and the album’s cultural/socio-political background together. Voodoo wouldn’t sound the way it does without Prince or 60s and 70s funk and soul; but neither could it have come from someone without D’Angelo’s own personal background in gospel and the African-American church, and Pennick, as an African-American woman responds to the album in ways that would be inaccessible to a white, male writer in Scotland if not for her book. Why an album sounds the way it does is always personal to the artist, but also specific to the era and culture they come from, and how an audience – on a mass or individual level – responds to that album adds depth to the work and determines its stature. Pennick brings these strands together seamlessly; concise, informal and yet powerful, in its own quiet way the book is a virtuoso performance, just as Voodoo is.