On the rare occasions that anyone asks me anything about my writing, it’s usually about music reviews. The consensus seems to be that a good review (I don’t mean a positive one) should either be ‘listen to the music and say if it’s good or bad’, or ‘listen to the music and describe it so that other people can decide whether it’s their cup of tea, but keep your opinion out of it’. As it happens, I’ve given this subject a lot of thought, not only because I write a lot of reviews, but I also because I read a lot of reviews, and some of my favourite writers (Charles Shaar Murray is the classic example) manage to make me enjoy reading about music even when it’s music that I either already know I don’t like, or that I can be fairly certain from reading about it that I won’t like. Because reading a good article about music is first and foremost ‘reading a good article’.

Anyway, over the course of pondering music reviews I have come to several (possibly erroneous) conclusions:

* “star ratings” HAVE TO BE relative and all stars don’t have the same value. For instance, one might give a lesser album by a great artist 3 stars, but those are not the same 3 stars one would give a surprisingly okay album by a generally crappy artist.

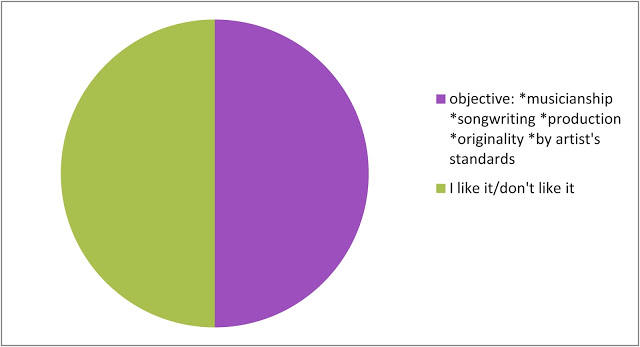

* Musical taste is, as everyone knows, entirely subjective, but reviewing (for me at least) has to try be a balance between objective and subjective; just listening to something and saying what you think of it is also valid of course.

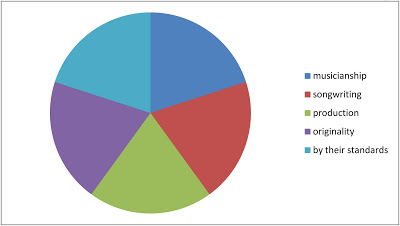

* Objective factors alone (see fun pie chart below) can never make an otherwise bad album good, but subjective factors can.

* ‘Classic’ albums make a nonsense of all other rules.

Let’s examine in more detail, with graphs! (are pie charts graphs?):

Objective factors:

Objective factors (see fun pie chart) are really only very important when the reviewer doesn’t like the music: when you love a song, whether or not the people performing it are technically talented musicians/pitch perfect singers etc is entirely irrelevant.

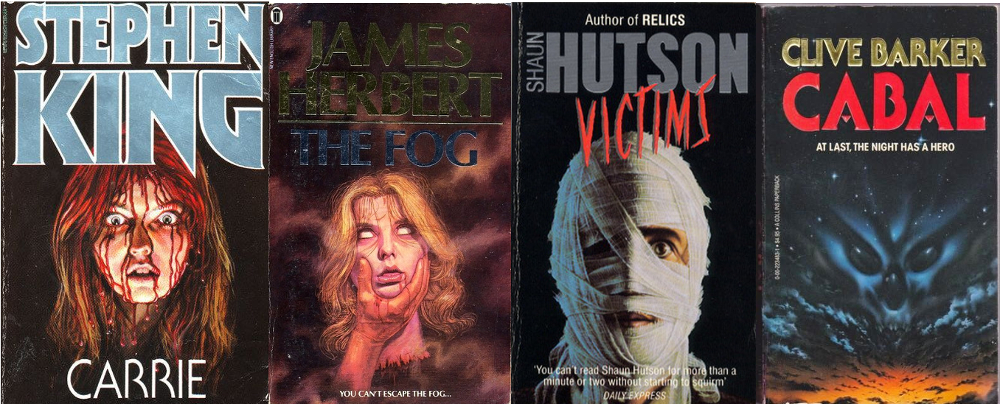

But, when an album or song (or movie, book etc) is dull or just blatantly abysmal, some comfort (or conversely, some outrage and annoyance) can be gained from the knowledge that at least the participants were good at the technical aspects of what they were doing, even if they are ultimately using those skills for evil.

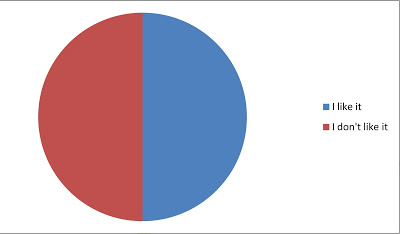

Subjective Factors:

Although there are many subjective factors that may be relevant; nostalgia for the artist/period, personal associations, all of these really amount to either you like it or you don’t; simple but not necessarily straightforward.

The positive subjective feeling ‘I like it!’ can override all else, so that an album which is badly played, unoriginal, poorly recorded and awful even by the artist’s own standards can receive a favourable review (though the reviewer will hopefully want to point out those things)

Meanwhile the negative subjective feeling ‘I don’t like it’ can’t help but affect a review, but should hopefully be tempered by technical concerns if (an important point) the reviewer feels like being charitable. They may not.

Ideally, to me a review should be something like 50% objective / 50% subjective (as in the examples somewhere below) but in practice it rarely happens.

“Classic” status:

The reviewing of reissued classics can be awkward, as ‘classic’ status in a sense negates reviewing altogether; it is completely separate from all other concerns, therefore said classic status can affect ratings just because the album is iconic and everyone knows it. Reviews of new editions of acknowledged classics usual become either a review of what’s new (remastered sound, extra tracks etc) or a debunking of the classic status itself; which as far as I know has never toppled a classic album from its pedestal yet.

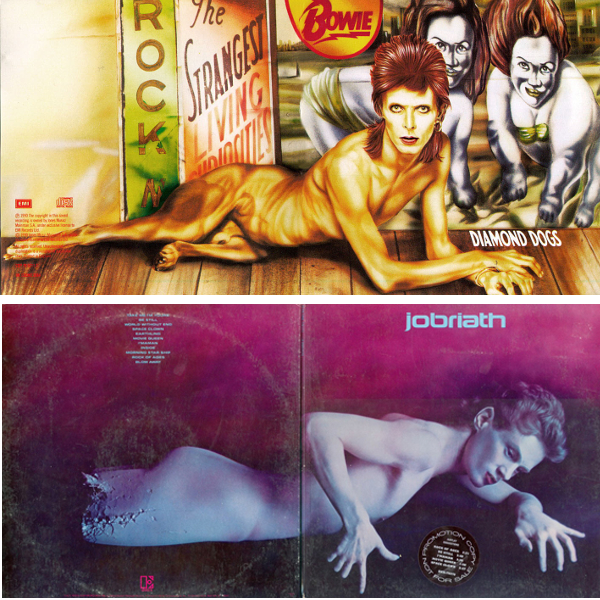

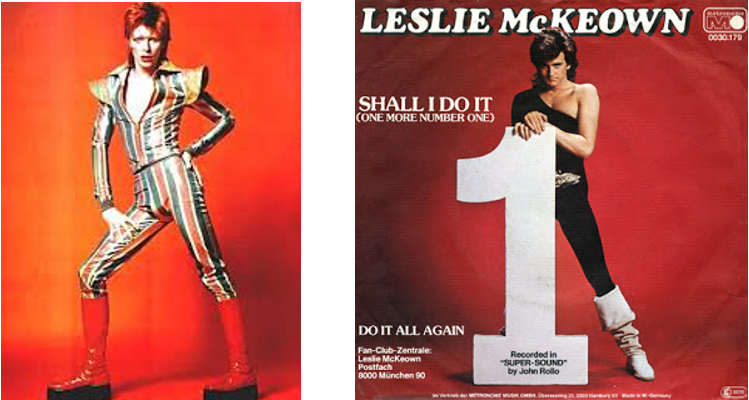

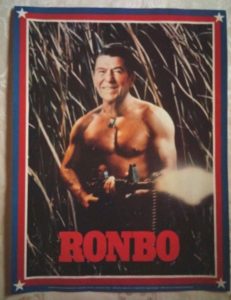

Classic album status is normally determined by popularity as much as any critical factors, but popularity itself shouldn’t play a part in the reviewer’s verdict; just because 30,000,000 people are cloth-eared faeces-consumers, it doesn’t mean the reviewer should respect their opinion, but they should probably acknowledge it, even if incredulously. Sometimes or often, classic status is attained for cultural, rather than (or as well as) musical reasons*, and it should be remembered that albums (is this still true in 2020? I don’t know) are as much a ‘cultural artefact’ (in the sense of being a mirror and/or record of their times) as cinema, TV, magazines or any other zeitgeist-capturing phenomenon.

* in their very different ways, Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, Thriller and The Spice Girls’ Spice were all as much ‘cultural phenomena’ as collections of songs

SO ANYWAY; how does this all work? Some examples:

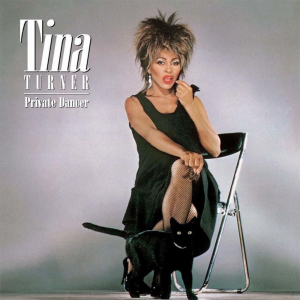

I once offended a Tina Turner fan with an ambivalent review of the 30th anniversary edition of Ms Turner’s 1984 opus Private Dancer.

As a breakdown (of ‘out of 10’s, for simplicity) it would look something like this:

TINA TURNER: PRIVATE DANCER (3OTH ANNIVERSARY EDITION)

Objective factors

* musicianship – 9/10 – hard to fault the adaptability or technical skill of her band

* songwriting – 6/10 – in terms of catchy, verse-chorus-verse efficiency & memorableness these are perfectly good songs, if a bit cheesy & shallow & therefore a waste of Tina Turner

* production – 9/10 – no expense was spared in making the album sound good in its extremely shiny, 80s way

* originality – 0/10 – as an album designed to make TT into a successful 80s artist, it wasn’t really supposed to be original, so hard to actually fault it in that respect

* by the standards of the artist – 2/10 – in the 60s/70s Tina Turner made some great, emotionally forceful, musically adventurous and just great records. In 1984 she didn’t.

Overall: 26/50 = 5.2/10

Subjective Factors

* I don’t like it: 1/10 (but not 0, because Tina Turner is a legend and it would be wrong to deny that somehow)

Overall 5.2/10 + 1/10 = 6.2/20 = 3.1/10 = 1.55/5 (round up rather than down, out of respect for Tina) = 2 stars

and in fact I did give the album two stars, though I didn’t actually do any of the calculations above; but it’s pleasing to find out that the instinctive two stars is justified by fake science.

by way of contrast, a favourite that seems to be an acquired taste at best:

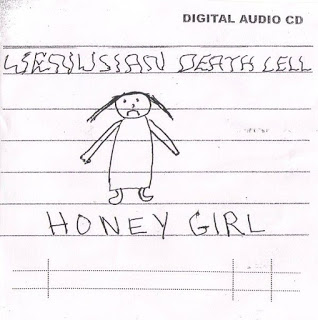

VENUSIAN DEATH CELL: HONEY GIRL (2014)

Objective factors

* musicianship – 1/10 – David Vora’s guitar playing is not very good, plus the guitar is out of tune anyway, and his drumming is oddly rhythm-free

* songwriting – 2/10 – the songs on Honey Girl are not really songs, they may be improvised, they don’t have actual tunes as such

* production – 0/10 – David pressed ‘record’ on his tape recorder

* originality – 10/10 – Vora doesn’t sound like anyone else, his songs are mostly not about things other people sing about

* by the standards of the artist – 9/10 – I like all of Venusian Death Cell’s albums, they are mostly kind of interchangeable, but Honey Girl is one of the better ones (chosen here over the equally great Abandonned Race only because of the uncanny similarities between the cover art of Honey Girl and Private Dancer).

Overall: 22/50 = 4.4/10

Subjective Factors

* I like it: 9/10 (but not 10, because if encouraged too much David Vora might give up and rest on his laurels. Though if he did that I’d like to “curate” a box set of his works)

Overall 4.4/10 + 9/10 = 13.4/20 = 6.7/10 = 3.35/5 (round up rather than down, out of sheer fandom) = 4 stars

And in fact I did give Honey Girl four stars, but I’ve yet to hear of anyone else who likes it. Which is of course fuel for the reviewer’s elitist snobbery; win/win

Star Ratings

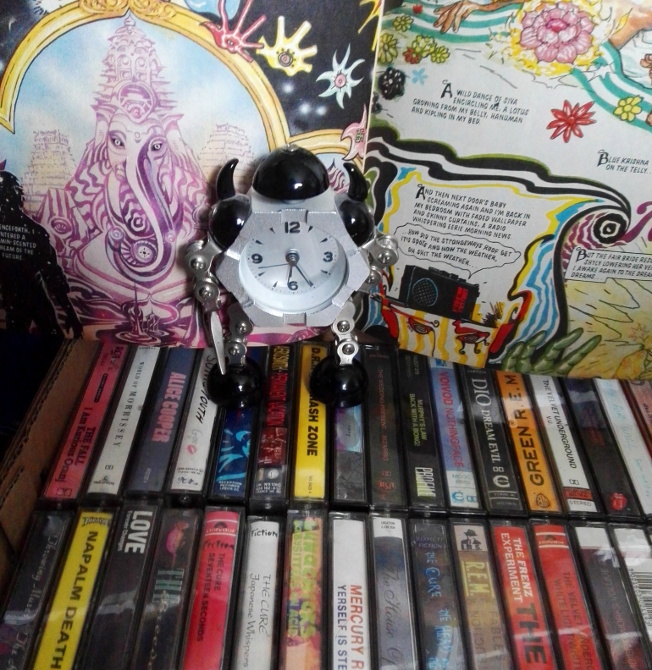

I’ve used scoring systems above, but the writers I like best rarely use scores or ‘star ratings’. I don’t think anybody (artists least of all) really likes star ratings or scores because they immediately cause problems; if, for instance, I give the Beach Boys’s Pet Sounds four stars (and the critical consensus says you have to; also, I do love it), then what do I give Wild Honey or Sunflower, two Beach Boys albums that are probably demonstrably ‘less good’, but which I still like more? But at the same time, I suppose scores are handy, especially for people who want to know if something is worth buying but don’t want an essay about it – and who trust the reviewer. The best ‘score’ system I’ve ever seen is in the early 2000s (but may still be going?) fanzine Kentucky Fried Afterbirth, in which the genius who writes the whole thing, Grey, gives albums ratings out of ten ‘cups of tea’ for how much they are or aren’t his cup of tea; This may be the fairest way of grading a subjective art form that there can possibly be.

Critical Consensus

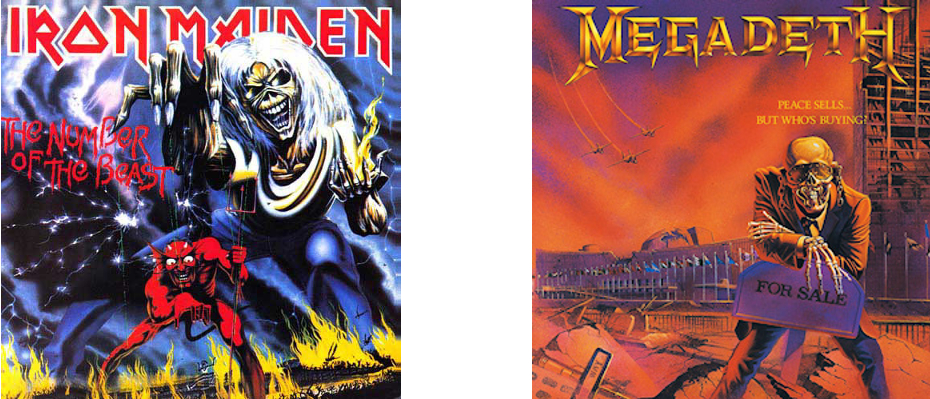

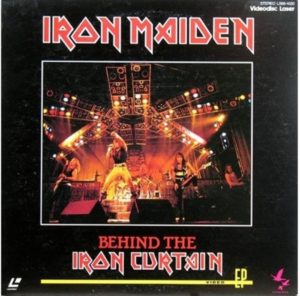

I mentioned the critical consensus above, and there are times when it seems that music critics seem to all think the same thing, which is how come there’s so much crossover between books like 1000 Albums You Must Hear Before You Die (I always feel like there’s an implied threat in those titles) and The Top 100 Albums of the Sixties etc. I’m not sure exactly how this works, because like most people I know who love music, my favourite albums and songs aren’t always (or even usually) the most highly regarded ones. My favourite Beatles album isn’t the ‘best’ one (Revolver, seems to be the consensus now); Songs in the Key of Life is the Stevie Wonder album, but it’s probably my third or fourth favourite Stevie Wonder album; I agree that Bruce Dickinson is a metal icon but I kind of prefer Iron Maiden with Paul Di’anno (granted PD wouldn’t be as good as Bruce at things like Rime of the Ancient Mariner but it’s less often mentioned that Bruce is definitely not as good at singing Wrathchild etc as Paul was.) Much as I genuinely love The Velvet Underground and Nico, I genuinely love the critically un-acclaimed Loaded just as much; there are so many examples of this that the idea of an actual critical consensus that means anything seems like nonsense.

I’ve been writing music reviews for many years now, but my own involvement with ‘the consensus’ is rare and the only solid example I can think of is a negative one. I thought – and I still think – that Land, the fourth album by Faroese progressive metal band Týr, is the best thing they’ve ever done. I gave it a good review, not realising that the critical tide was turning against the band, and, for whatever reason (fun to speculate but lack of space is as likely as anything), my positive review never appeared in print. It wouldn’t have made any real difference to the band or to the album’s reception in general, but it did make me feel differently about albums that are notoriously bad (or good). Who is deciding these things? I’m a music critic and I’m not. And although I – like, I think everyone – take reviews with a pinch of salt anyway (someone else liking something is a strange criteria for getting it, when you think about it), I have to admit if I hadn’t had to listen to Land (which I still listen to every now & then, over a decade later), I wouldn’t have been in a hurry to check out the album after reading again and again that it was dull and boring.

Throughout this whole article the elephant in the room is that, at this point, the whole system of reviewing is out of date. You can almost always just listen to pretty much anything for free and decided yourself whether you like it, rather than acting on someone else’s opinion of it. But in a way that makes the writing more important; again, like most people, I often check things out and stop listening at the intro, or half way through the first song if I just don’t like it – except when I’m reviewing. Reviewers have to listen to the whole thing, they have to think about it and say something relevant or contextual or entertaining.* And if the reviewer is a good writer (Lester Bangs is the most famous example, though I prefer Jon Savage or the aforementioned CSM and various nowadays people), their thoughts will entertain you even if the music ultimately doesn’t.

*worth a footnote as an exception which proves the rule is a notorious Charles Shaar Murray one-word review for the Lee Hazlewood album Poet, Fool or Bum: “Bum.”

I am (as I think most people probably are!) quite fussy about death metal, but without being retro in any kind of self-conscious way, De Profundis make music that would sit happily in the late 80s/early 90s death metal scene. The Blinding Light of Faith is an album that can hold its own in the company of any of the big names of death metal; superb, intelligent musicianship and songwriting – it’s a seriously impressive album.

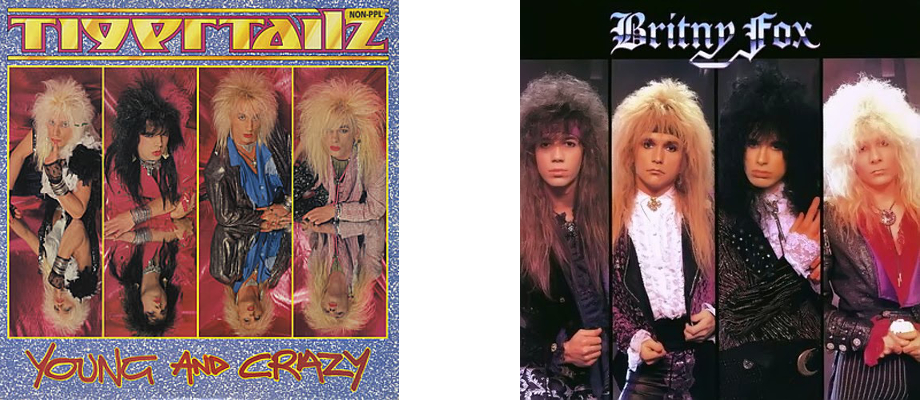

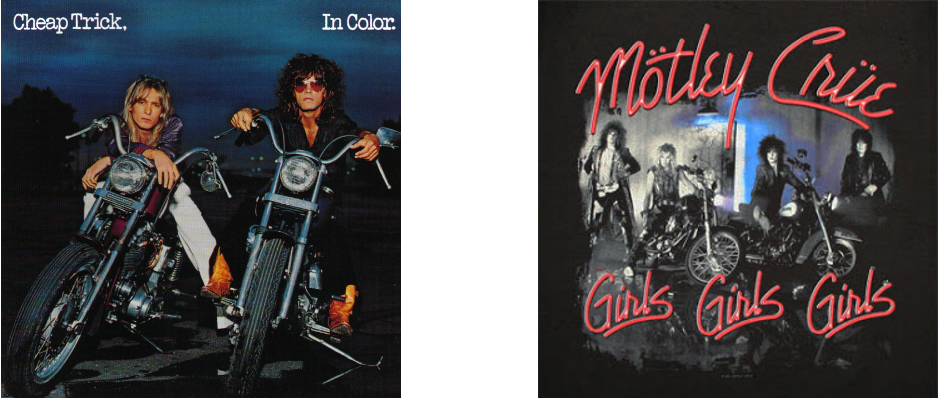

I am (as I think most people probably are!) quite fussy about death metal, but without being retro in any kind of self-conscious way, De Profundis make music that would sit happily in the late 80s/early 90s death metal scene. The Blinding Light of Faith is an album that can hold its own in the company of any of the big names of death metal; superb, intelligent musicianship and songwriting – it’s a seriously impressive album. 80s veteran(s) Lizzy Borden (both a singer and a band) seem always to suffer from being mis-pigeonholed, whether as a glam band (he/they did have the image), Twisted Sister clones (ditto), or some kind of Alice Cooper-esque horror-metal act (partly the name, partly the image innit), but if you listen back to the best of the band’s 80s work, especially Love You To Pieces, they were really a classic metal band, more Iron Maiden-meets-W.A.S.P. than Motley Crue. On the new album Lizzy himself takes centre stage, singing better than he ever has – no mean feat – and playing all the guitars on what is a very song-based album. It’s not very heavy – more a kind of homage to bands like Cheap Trick and Queen than the early 80s Lizzy Borden sound. But it’s really good if you like that kind of thing, and it’s great to hear Lizzy really going for it after a couple of slightly patchy, compromised-sounding, ‘not bad’ records.

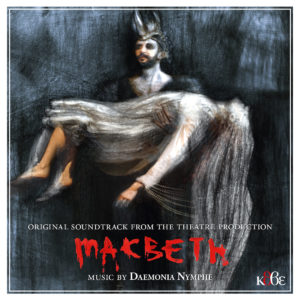

80s veteran(s) Lizzy Borden (both a singer and a band) seem always to suffer from being mis-pigeonholed, whether as a glam band (he/they did have the image), Twisted Sister clones (ditto), or some kind of Alice Cooper-esque horror-metal act (partly the name, partly the image innit), but if you listen back to the best of the band’s 80s work, especially Love You To Pieces, they were really a classic metal band, more Iron Maiden-meets-W.A.S.P. than Motley Crue. On the new album Lizzy himself takes centre stage, singing better than he ever has – no mean feat – and playing all the guitars on what is a very song-based album. It’s not very heavy – more a kind of homage to bands like Cheap Trick and Queen than the early 80s Lizzy Borden sound. But it’s really good if you like that kind of thing, and it’s great to hear Lizzy really going for it after a couple of slightly patchy, compromised-sounding, ‘not bad’ records. Away from metal, this is a really interesting, good album if you like – well, what? “Film soundtrack music” isn’t really a genre, is it, but that’s what Fire Behind The Curtain makes me think of. I’ve seen it described as neoclassical and minimalist too, but neither of those feels quite right to me. It’s a beautifully cohesive-yet-eclectic collection of mostly-instrumental pieces vary from haunting and bleakly forbidding atmospheres to warm and embracing melodies.

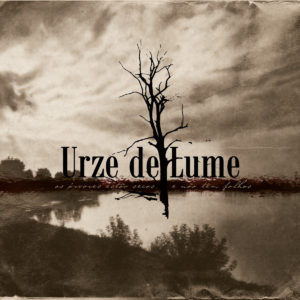

Away from metal, this is a really interesting, good album if you like – well, what? “Film soundtrack music” isn’t really a genre, is it, but that’s what Fire Behind The Curtain makes me think of. I’ve seen it described as neoclassical and minimalist too, but neither of those feels quite right to me. It’s a beautifully cohesive-yet-eclectic collection of mostly-instrumental pieces vary from haunting and bleakly forbidding atmospheres to warm and embracing melodies. I can’t really write an awful lot about this album from the always-dependable I Heart Noise label, as I’ve only just started listening to it really; but so far I love it. It makes me think of Lou Reed, or Alan Vega covering John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band album; sparse, forlorn, world-weary and a little bit sleazy.

I can’t really write an awful lot about this album from the always-dependable I Heart Noise label, as I’ve only just started listening to it really; but so far I love it. It makes me think of Lou Reed, or Alan Vega covering John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band album; sparse, forlorn, world-weary and a little bit sleazy.

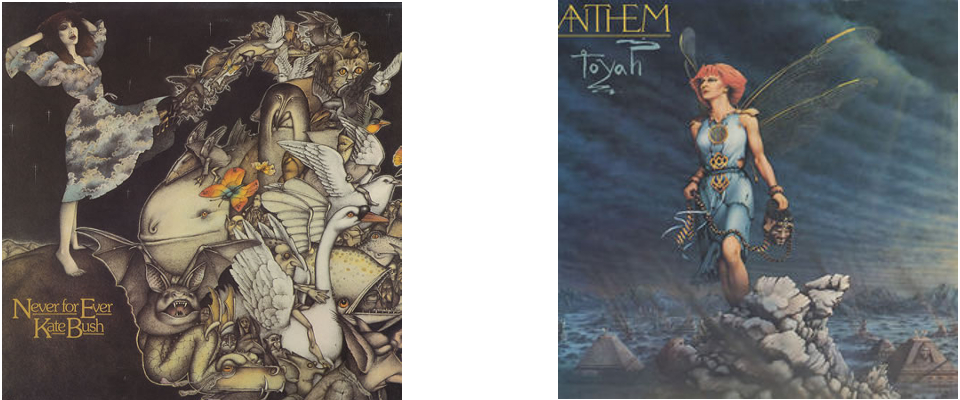

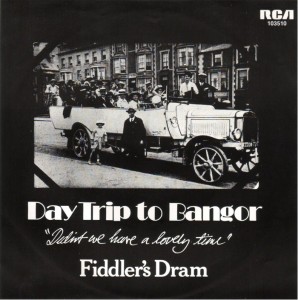

But what did I hear first? Who knows? I remember my mother playing guitar and singing, but ridiculously, the actual song that stands out as the first identifiable thing I remember, can name and even know some of the words to is neither parent music, nor standard chart fare; it’s Day Trip To Bangor by Fiddler’s Dram, which sets the date I began to really absorb music at around 1979; which makes sense, as until around that point I had hearing problems. As earliest memories go it could be more significant – I didn’t like it (or dislike it, as far as I remember), I can’t picture the band, it isn’t the soundtrack to a specific event. I just remember it, like I remember Crown Court and Pebble Mill At One being on TV in the afternoon if I was ill at home instead of being at school. It’s also to the end of the 70s that the first 7” single actually owned by me belongs and it’s also a typical-of-its-era novelty record, by the already long-in-the-tooth comedy group The Barron Knights – ‘A Taste of Aggro’. It’s the kind of random thing that little kids like; it features parodies of ‘The Smurf Song’ and Boney M’s ‘Rivers of Babylon’ (‘there’s a dentist in Birmingham…’ ). In my first year or two at primary school I also remember liking at least one Adam and the Ants song, I liked Toyah and Hazel O’Connor when they were on TV, I liked the disco version of the Star Wars theme and ‘Cars’ by Gary Numan. Other music-related memories of the time are pretty vague; I remember older kids who were punks and (more scary to small-child me) skinheads, but I don’t think I ever heard their music at the time.

But what did I hear first? Who knows? I remember my mother playing guitar and singing, but ridiculously, the actual song that stands out as the first identifiable thing I remember, can name and even know some of the words to is neither parent music, nor standard chart fare; it’s Day Trip To Bangor by Fiddler’s Dram, which sets the date I began to really absorb music at around 1979; which makes sense, as until around that point I had hearing problems. As earliest memories go it could be more significant – I didn’t like it (or dislike it, as far as I remember), I can’t picture the band, it isn’t the soundtrack to a specific event. I just remember it, like I remember Crown Court and Pebble Mill At One being on TV in the afternoon if I was ill at home instead of being at school. It’s also to the end of the 70s that the first 7” single actually owned by me belongs and it’s also a typical-of-its-era novelty record, by the already long-in-the-tooth comedy group The Barron Knights – ‘A Taste of Aggro’. It’s the kind of random thing that little kids like; it features parodies of ‘The Smurf Song’ and Boney M’s ‘Rivers of Babylon’ (‘there’s a dentist in Birmingham…’ ). In my first year or two at primary school I also remember liking at least one Adam and the Ants song, I liked Toyah and Hazel O’Connor when they were on TV, I liked the disco version of the Star Wars theme and ‘Cars’ by Gary Numan. Other music-related memories of the time are pretty vague; I remember older kids who were punks and (more scary to small-child me) skinheads, but I don’t think I ever heard their music at the time.

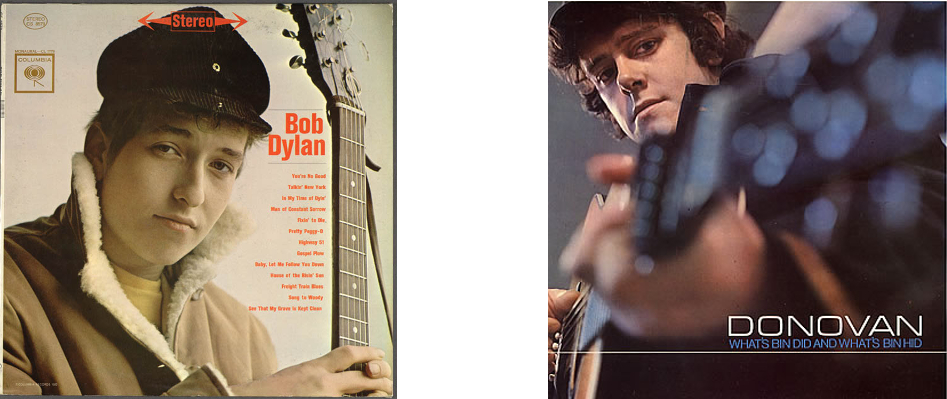

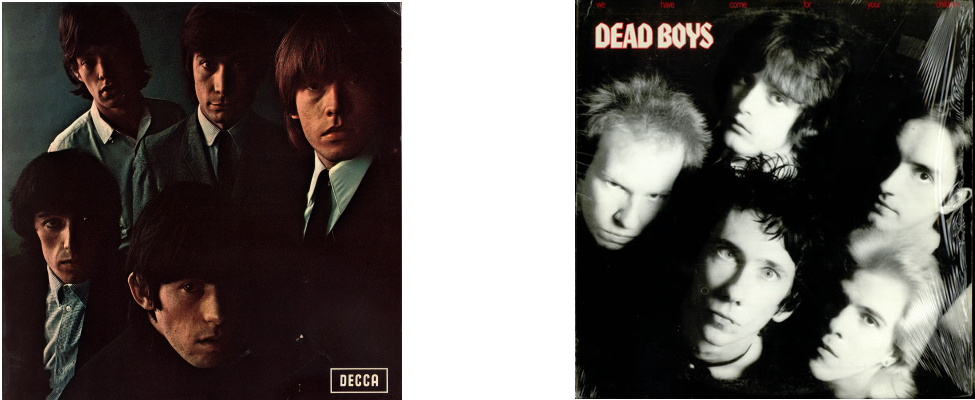

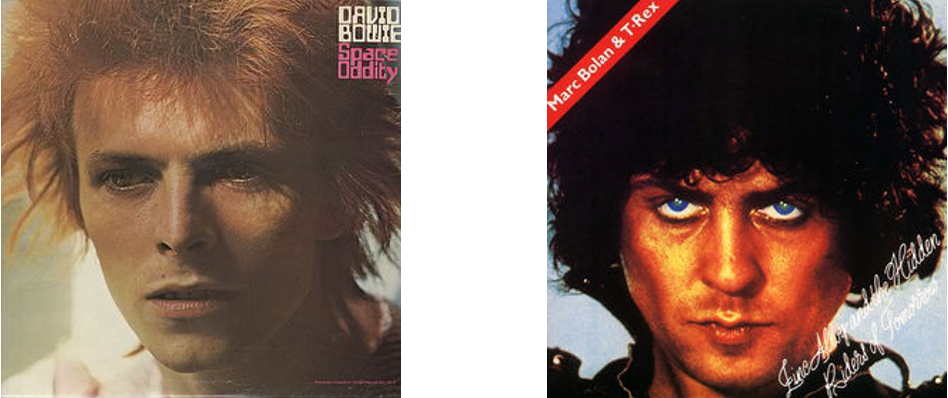

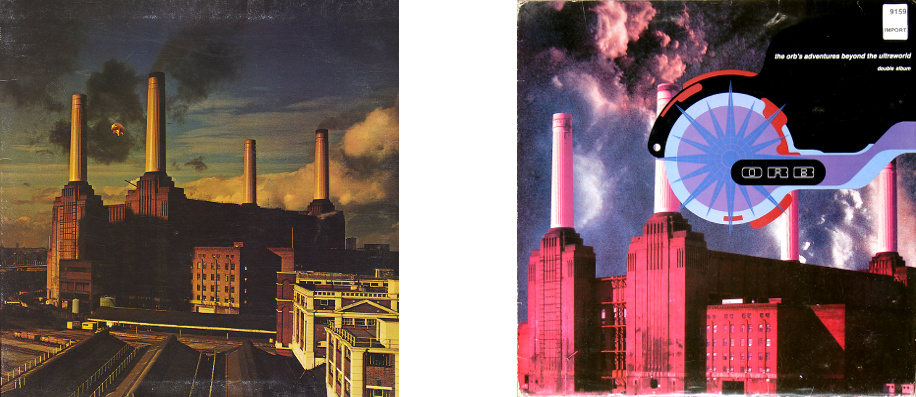

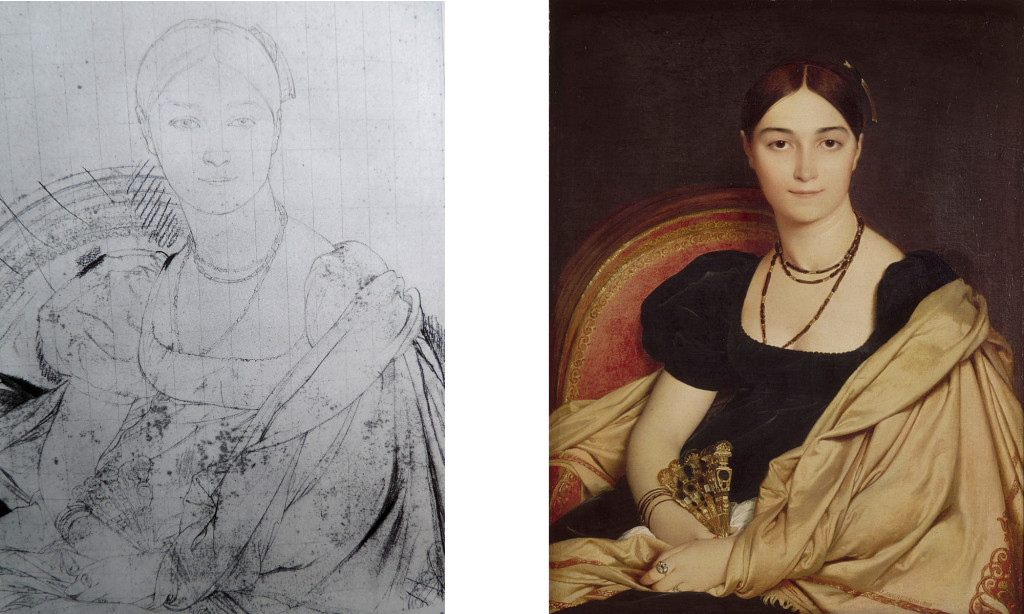

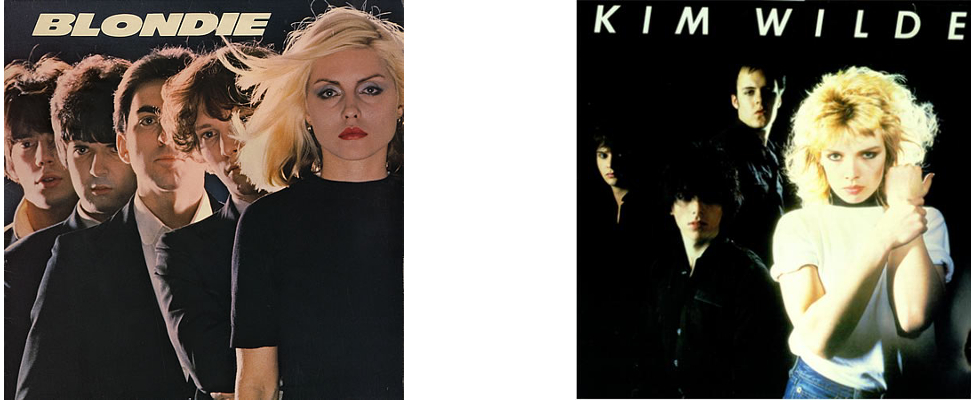

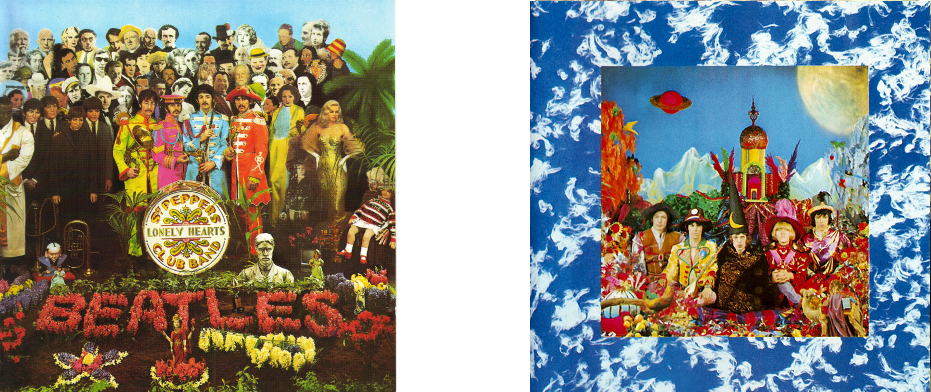

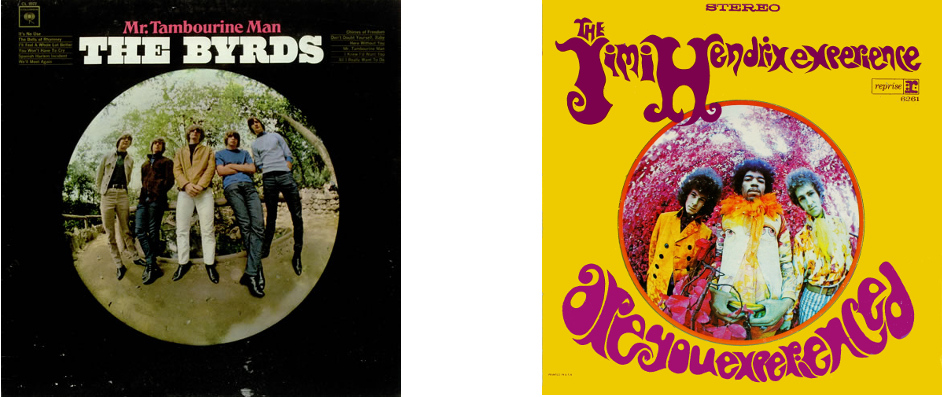

This comparison really traces the advance of psychedelia from a mild distortion of perception to a neon-coloured hallucination over the two years 1965-67

This comparison really traces the advance of psychedelia from a mild distortion of perception to a neon-coloured hallucination over the two years 1965-67