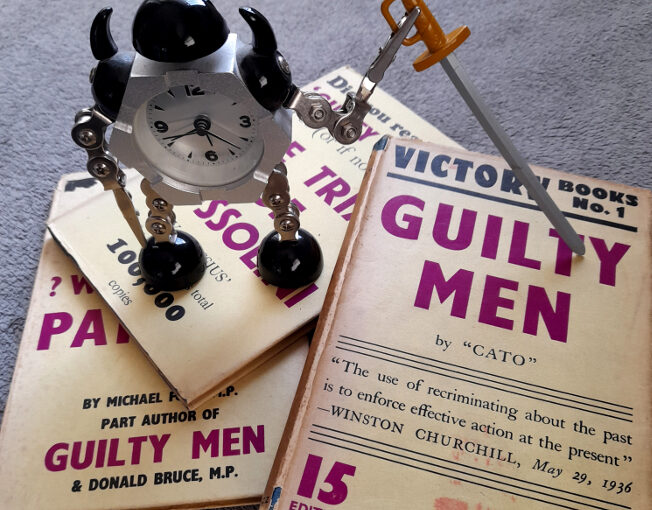

Everyone knows that history is written by the victors, but I’m not sure it’s always realised – or I should say that I hadn’t considered – how much of a privilege that is. Of course there are the obvious material, societal privileges that come with winning, but I’m thinking specifically about history and the way it’s transmitted.

This little epiphany came while watching the now ten-year-old show, Tony Robinson’s Wild West. It’s not a piece of history that generally interests me, but Robinson belongs to the last generation for whom ‘cowboys and Indians’ occupied a major place in popular culture – and he is also a presenter who tends to look at history from a point of view that conservative critics would call postmodern; i.e. he tends to think that history is complicated and acknowledges injustices, calls exploitation exploitation and that kind of thing, and so it piqued my interest. But one of the unexpected consequences of making an enlightened history show is the focus it places on experts and the way that they come across.

I don’t mean to condemn the historians I’m talking about here; most historians are in some ways at least, enthusiasts for their subject. The best ones (in my experience) have a special, and sometimes quite a nerdy, bond with the period and people that they have chosen to study. When I studied ancient history, one of the best lecturers I had was a specialist on ancient Greece who had seemingly based his physical appearance on the look of Greek men on ancient red-figure pottery; curly hair, big beard and all. And there was a historian of Rome in my Classical Studies course with a ‘Julius Caesar’ haircut. It feels natural that someone would want to immerse themselves in the civilisation which fascinates them enough to make it their life’s work.

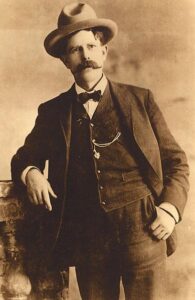

And so it makes sense that some of the historians in Tony Robinson’s Wild West, with their (to British eyes) Edwardian moustaches and waistcoats should look as though they are tending the bar in a saloon in Calamity Jane, or are speaking to the camera from the frontier, while wearing their fringed buckskin jackets. It’s kind of comical, but also isn’t, in the context of that history. The clothes seem like a concession to the romanticism of the Old West, but these are modern historians, and despite being occasionally slightly squeamish about the history they are recounting, and tending to overstate the balance of power in the ‘Indian wars’ they make no serious attempt to whitewash it.

But it feels significant that the Lakota historian talking about the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890 wasn’t wearing historical fancy dress, and it would seem strange if he was. And it’s the discussion of atrocities like Wounded Knee that remind you that the victor writes the history. To paraphrase the Lakota historian, Wounded Knee is framed as a war crime, because that feels historically, appropriate – but in fact there was no war – it was just a crime, albeit one committed by a government. And nakedly genocidal attitudes at the time, encapsulated by a quotes from L. Frank Baum, author of – of all things – the Wizard of Oz and its sequels, make the buckskins, waistcoats and archaic facial hair and fashions of the Western historians seem somewhat incongruous.

Hearing of the death of Sitting Bull in the aftermath of Wounded Knee, Baum wrote in his popular newspaper:

The proud spirit of the original owners of these vast prairies inherited through centuries of fierce and bloody wars for their possession, lingered last in the bosom of Sitting Bull. With his fall the nobility of the Redskin is extinguished, and what few are left are a pack of whining curs who lick the hand that smites them. The Whites, by law of conquest, by justice of civilization, are masters of the American continent, and the best safety of the frontier settlements will be secured by the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians. Why not annihilation? Their glory has fled, their spirit broken, their manhood effaced; better that they die than live the miserable wretches that they are.

Though thankfully not, or not quite, enacted, this wasn’t a controversial view at the time. But with even with a little knowledge of the historical context (there had been a government policy explicitly called the Indian Removal Act only 50 years earlier), its knowing blatancy is shocking. It’s one thing to talk or read about massacres of Greeks or Spartans or Persians thousands of years ago; it’s quite another to think of it happening in the time of your own great-grandparents, or to think of it happening elsewhere literally as I write these words.

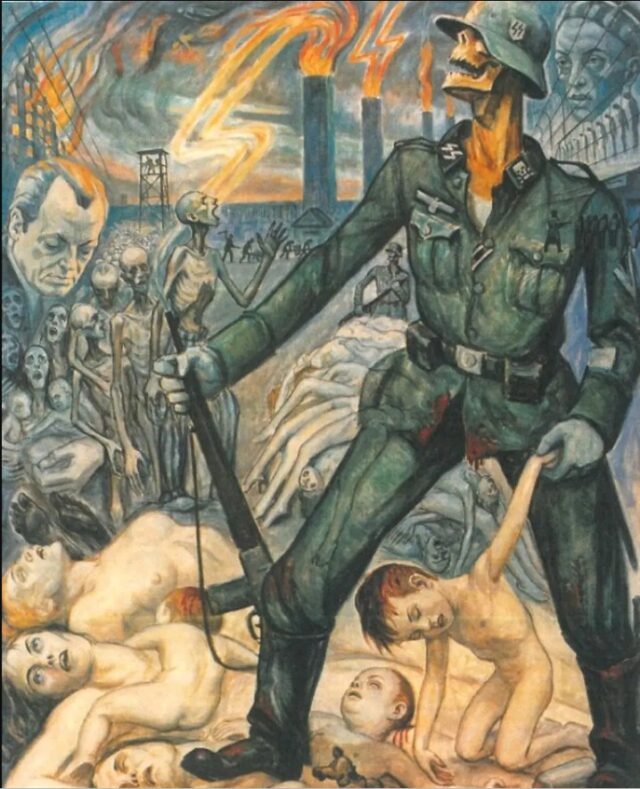

It’s an obvious, problematic and quite cheesy comparison to make, but I’ll make it. Had things worked out differently, a situation where a historian could sit in a black shirt and swastika armband, talking about World War Two – acknowledging quite reasonably the terrible things that were done on both sides, but talking, in an essentially neutral way about the formation of modern Europe, while a far more sombre Jewish historian shows us the Auschwitz museum, is almost unimaginable. And yet – judging by the way these things actually work – it’s not an especially outlandish alternate present.

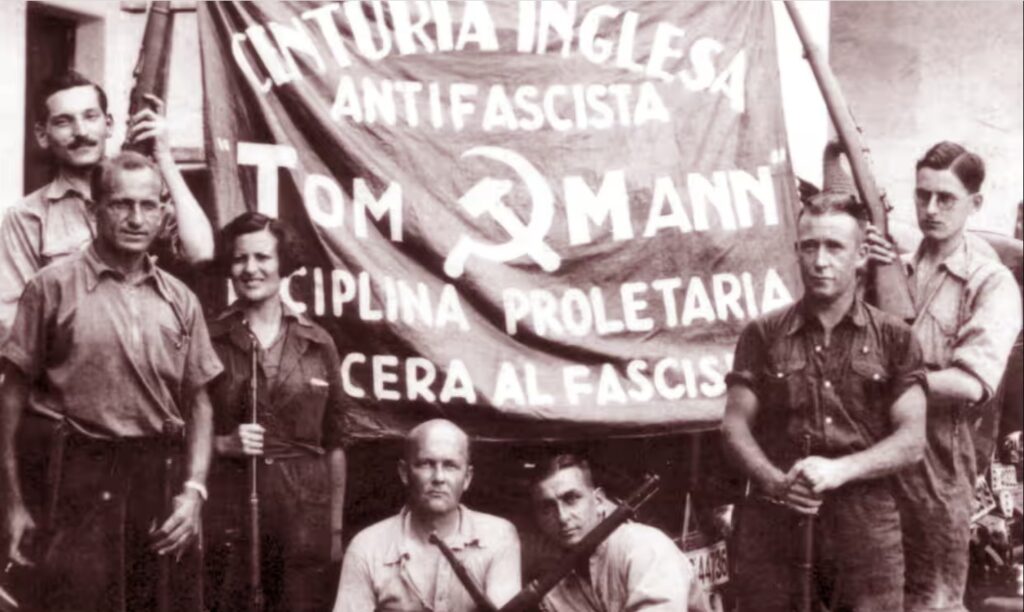

Not only is history written by the victors, but the world we live in is forged by them, and generations on from winning an overwhelming victory they are no longer ‘they,’ they are just us. But that takes time.

The historian who loves ancient Greece can afford to love it, wherever they come from. Greece was barbaric as well as enlightened, Greece had slaves and was misogynistic – but Greece is only what we call it now for convenience; the collection of independent city states and relatively heterogynous cultures we now call ‘ancient Greece’ is not the same as the country Greece. “Rome” is not Italy. The world – especially but not exclusively the western world – has benefitted from ancient Greek and Roman culture and though it’s easy to argue for its negative influence too, that’s less the fault of those ancient people than it is our more recent ancestors who understood those cultures in the way they could and wanted to understand them.

Regarding America, and Britain and everywhere else, all of that may come, in a thousand years or so, when the state of the world will probably be as unimaginable to us now as the internet would be to Herodotus. But. There are photographs of the mass graves being dug at Wounded Knee and while the winners of the ‘Indian wars’ were able to impress their culture on the country and to define that recent history in terms of expansion, exploration and consolidation, the other side of the story is still living history too. And the losers get to just live with it and tell their stories to whoever will listen.

It’s fair to say that the nature of the conquest of America – not just the 1800s and the Old West, but everything from the founding of the first colonies to the establishment and erosion of the reservations – has never been forgotten, but it’s only relatively recently that it’s been publicly acknowledged. Tony Robinson’s television show came about precisely because he belongs to a generation – my father’s generation – where young boys were entertained by stories of heroic cowboys fighting savage Indians in a way that now looks – despite the inevitable messiness of history as opposed to fiction – like an almost perfect inversion of the facts. And I belong to one of the first generations where it hasn’t been popularly presented that way.

It’s never too soon to be passionate about history or to tell the truth about it, but even though it’s always nice to find yourself on the winning team, when that happens it’s probably worth considering what it really means and how you got there. And if the dressing up still feels appropriate, then by all means go for it.

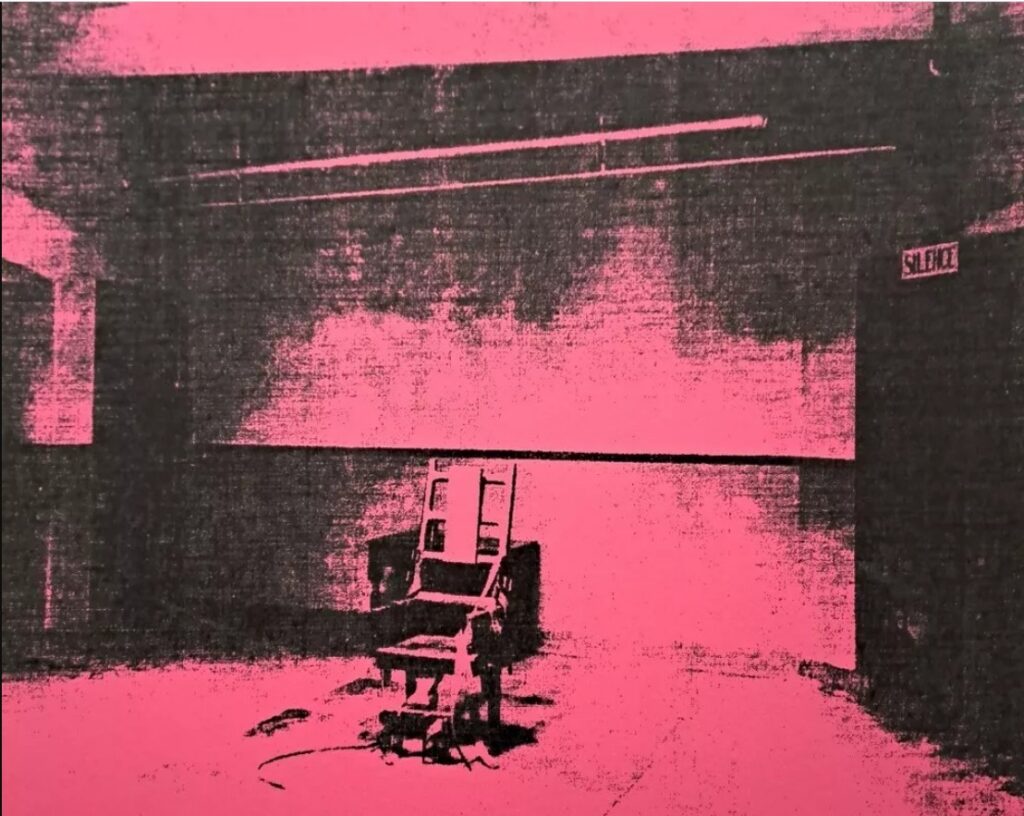

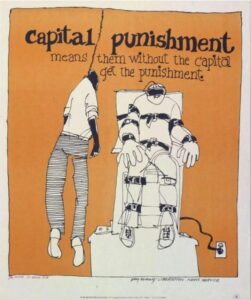

The current case of Luigi Mangione is far stranger. It’s the only time I can recall that the supporters (in this case I think ‘fans’ would be just as correct a word) of someone accused of murder want the suspect to be guilty rather than innocent. Whether they would still feel that way if he looked different or had a history of violent crime or had a different kind of political agenda is endlessly debatable, but irrelevant. It looks as if the State will be seeking the death penalty for him and for all the reasons listed above I think that’s wrong. But assuming that he is guilty, which obviously one shouldn’t do (and if he isn’t, Jesus Christ, good luck getting a fair trial!) Mangione himself and some of his fans, should really be okay with it. If he’s guilty, he hasn’t done anything to help a single person to get access to healthcare or improve the healthcare system or even protested against it in a way that people with the political power to affect change can positively react to. UnitedHealthcare still has a CEO, it still has dubious political connections and it still treats people very badly. That doesn’t mean that it’s an unassailable monolith that can never be changed, but clearly removing one figurehead isn’t how it can be done.

The current case of Luigi Mangione is far stranger. It’s the only time I can recall that the supporters (in this case I think ‘fans’ would be just as correct a word) of someone accused of murder want the suspect to be guilty rather than innocent. Whether they would still feel that way if he looked different or had a history of violent crime or had a different kind of political agenda is endlessly debatable, but irrelevant. It looks as if the State will be seeking the death penalty for him and for all the reasons listed above I think that’s wrong. But assuming that he is guilty, which obviously one shouldn’t do (and if he isn’t, Jesus Christ, good luck getting a fair trial!) Mangione himself and some of his fans, should really be okay with it. If he’s guilty, he hasn’t done anything to help a single person to get access to healthcare or improve the healthcare system or even protested against it in a way that people with the political power to affect change can positively react to. UnitedHealthcare still has a CEO, it still has dubious political connections and it still treats people very badly. That doesn’t mean that it’s an unassailable monolith that can never be changed, but clearly removing one figurehead isn’t how it can be done.