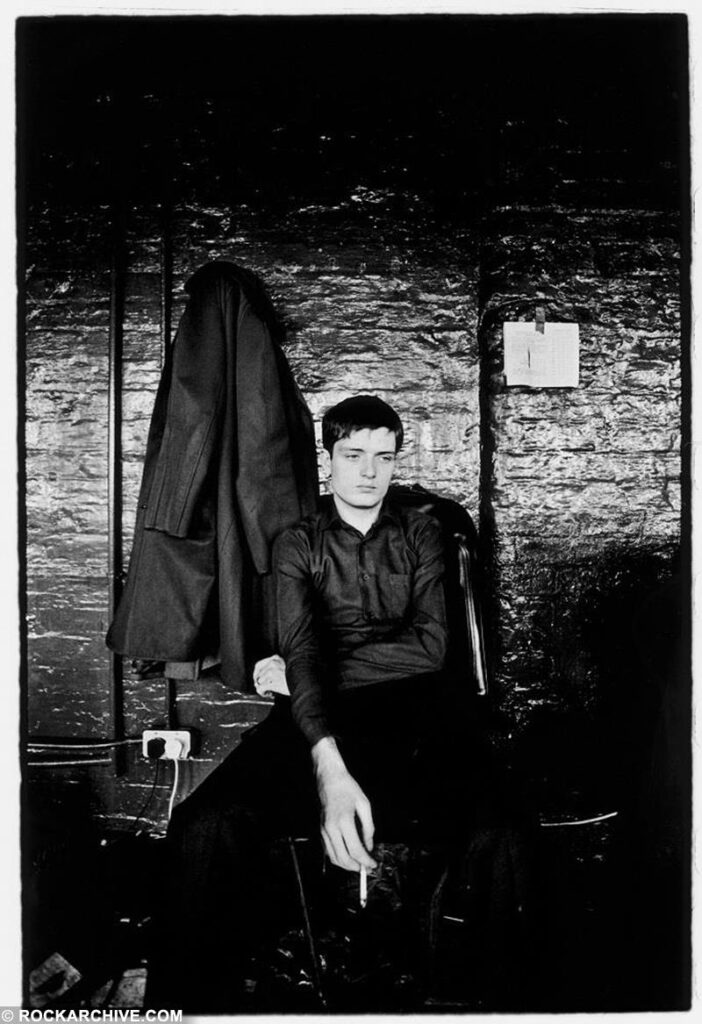

A question occurred to me while watching a documentary about Joy Division ; is there any better ending to a song than Ian Curtis bellowing FEELING FEELING FEELING FEELING FEELING FEELING FEEEEEELING! as the music clatters to a halt at the end of “Disorder”? Lyrically, despite its explosiveness, it isn’t cathartic, but in a musical way it is – for the listener at least – because until that point, the tempo has been too fast and the lyrics too complex for Curtis’s voice to do whatever the deep, melancholy equivalent of ‘taking flight’ is. There’s an underappreciated art to ending songs and it’s not something that even great bands do infallibly or that all great songs feature. Not all songs need to end with a crescendo or flourish, and very few songs benefit from just grinding to a halt or being cut off mid-flow, but the sense of completeness when a song (especially a relatively short song) ends perfectly is one of the things that makes you want to hear it again.

“Decades,” the final song on Closer, the final Joy Division album, is one of relatively few songs (given their vast number) where fading out at the end doesn’t seem like a cop out. There’s nothing wrong with fading out a song, but often it just feels like an easy option taken in order to dodge the question of how to end a song properly. Which is fine, except in live performances, where it’s difficult to satisfactorily replicate a fade-out. Partly that’s because of the practicality of it – does the band all try to play more quietly? Do they just get the sound person to turn down the volume, which works, unless you’re close to the stage, which, in that situation is sub-optimal, since hearing the unamplified sounds from the stage (drums clattering, guitars plinking etc) is kind of a mood-killer? And if so, when do they all stop? There’s also the awkwardness of the audience reaction; the crowd might start cheering/jeering before the song is actually finished, or they might not start until someone in the band indicates that that the song is definitely over, which is also not ideal. Basically, it feels artificial – but obviously it has the appeal of being simple – haven’t thought of a proper ending for you song? Just keep playing and fade it out afterwards. But Closer needed to fade into silence and it does.

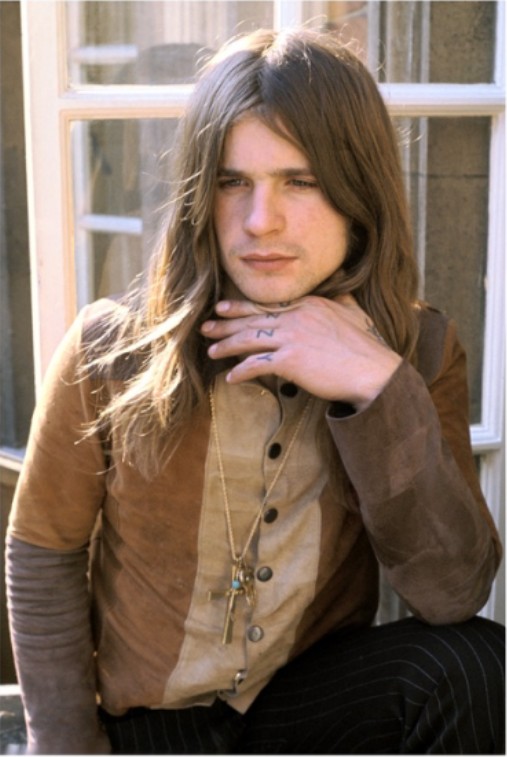

Another musical ending this week – a seriously clunky segue this but bear with me – was the death of Ozzy Osbourne, a week after what was explicitly intended to be his final performance, a different kind of ending and a very unusual one in the music world where ‘farewell’ tours can become an annual occurrence and no split is too acrimonious to be healed by the prospect of bigger and bigger sums of money.

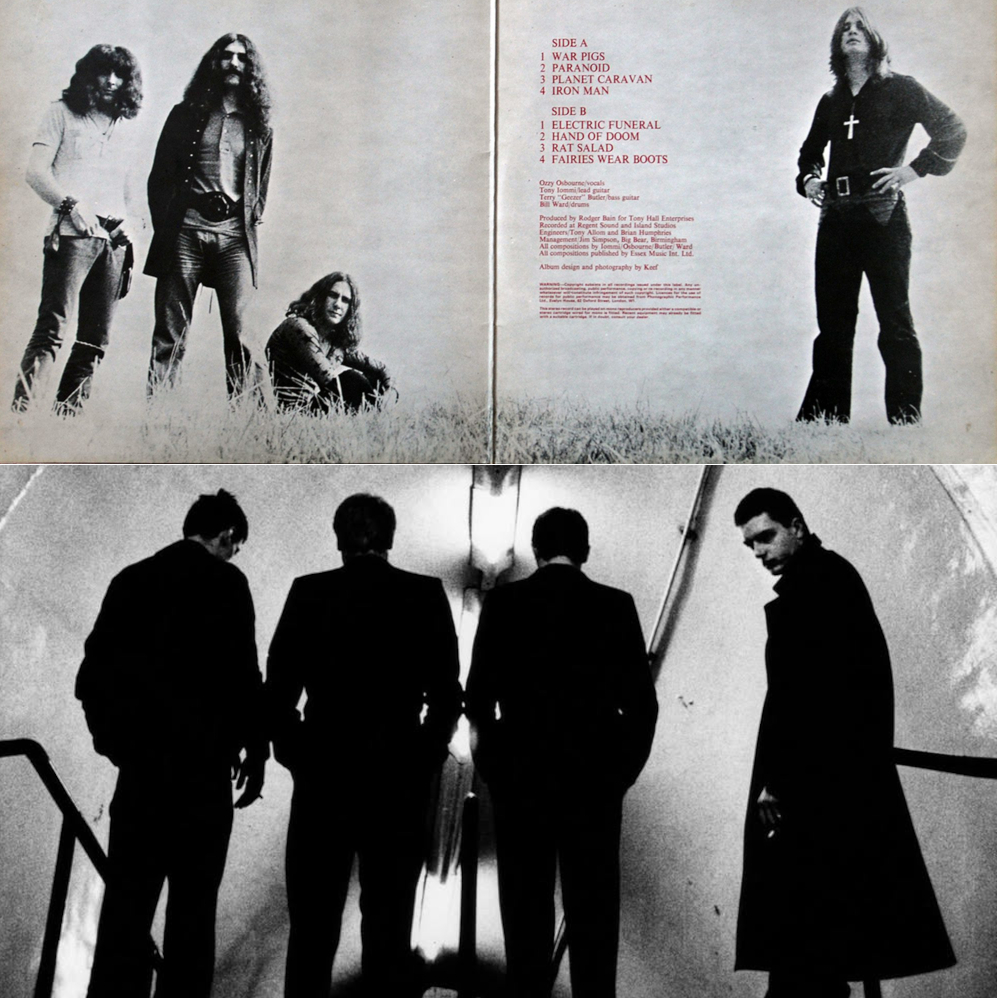

On paper, any kinship between Ozzy and Joy Division seems unlikely to say the least, but the ears say otherwise. Regardless of the punk roots of Joy Division, the only real precursor to a song like “New Dawn Fades” from their 1979 debut album Unknown Pleasures is Black Sabbath. And it’s not only the oppressively doomladen atmosphere, though that’s important; Bernard Sumner’s opening guitar melody is remarkably like Tony Iommi’s melodic solo from “War Pigs” – a classic song, incidentally, which has one of the worst endings of any great song ever written. Presumably, Black Sabbath had no idea how to end it and so did something worse than a fade out; speeding it up until it ends with a comical squeak. Oh well. But anyway, there are many moments, especially on Unknown Pleasures, where Joy Division sound like a cross between Black Sabbath and the Doors, although I’m sure neither of those things were in the minds of Peter Hook, Bernard Sumner, Stephen Morris and Ian Curtis, any more than they were in the consciousness of the music journalists who lauded the band in ’79, who mostly tended to see punk as year zero, the new beginning from which the influence of anything pretentious or overblown had been erased.

That basic idea was one I also accepted without much thought as a teenage indie fan in the early 90s when Joy Division – by then defunct for a decade – became one of my favourite bands. With the honourable, weekly music paper-approved exception of the Velvet Underground, I was dubious about anything old or anything that I considered overtly commercial. Without giving it much thought I just assumed that mentality came from my reading of Melody Maker and the NME. I had definitely accepted their pre-Britpop genealogy of cool rock music that essentially began with the Velvet Underground and then continued via punk and post-punk into 80s indie guitar music, most of which existed firmly outside of the mainstream of the UK top 40. But reflecting on Ozzy on the news of his death, it seems my snobbery has older roots.

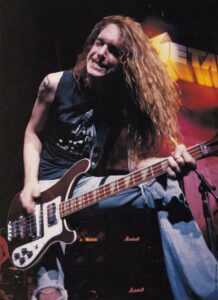

I don’t remember when I first heard Ozzy Osbourne’s name, but I do remember when I first heard his music. It was 1988 and I was about a year away from growing out of metal, but still immersed in it for the time being. Within metal itself I had fairly wide taste and my favourite bands included many of the biggest metal bands of the era; Iron Maiden, Metallica, Guns ‘n’ Roses, Helloween, Megadeth, Suicidal Tendencies, Queensrÿche, Slayer, Anthrax, plus many more. At that point I mostly discovered music via magazines (especially Metal Forces) and my friends. In addition to my modest collection of records and tapes I had many more cassettes that had been made for me by friends and I spent a good bit of my spare time making tapes for them; it was fun. And so; Ozzy. A friend had taped a couple of albums for me on a C90 cassette (the odd pairing, it seems now, of Mötley Crüe’s Girls, Girls Girls and Slayer’s Reign in Blood) and filled up the rest of the tape with random metal songs, among them “Foaming at the Mouth” by Rigor Mortis, “The Brave” by Metal Church, “Screamin’ in the Night” by Krokus and Ozzy’s latest single, “Miracle Man”. I pretty much hated it. I thought Ozzy’s voice was unbearably nasal and awful and the production really harsh and tinny (that was probably just the tape though).

By then, I knew who Ozzy was, and was aware of his bat-biting notoriety, though that definitely seemed to be a bigger deal in the USA than it was in the UK (or at least in my corner of rural Scotland). At some point just a little later, Cassandra Peterson, or more accurately Elvira, Mistress of the Dark presented a short series of metal-related shows for the BBC. One episode included Penelope Spheeris’ fantastic documentary The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years, which includes one of my favourite Ozzy interviews, but also concert footage of Ozzy during his ‘mad housewife’ era when his image seemed to be based on Jackie Collins’s style at the time. I love that era of Ozzy now, but at the time I thought it was laughably awful. It must have been around that time that I also became aware of Ozzy’s history with Black Sabbath, who I only knew in their then-current incarnation with Tony Martin, which again I now love but at the time thought irremediably middle aged and boring. The fact that Ozzy’s Black Sabbath was from the 70s meant that I pretty much dismissed them without needing to hear them. When Elvira showed a classic early Led Zeppelin concert in black and white I also found that tiresomely old and dull, especially in comparison with the Napalm Death concert she presented. It’s hard to relate to now, but in the 80s, for me – and I think for most people I knew of my age – the 70s was cheesy, embarrassing and possibly funny, but with no redeeming features. Actually, that’s how the 80s were for a good part of the 90s too; changed days.

Again, like most of the metal fans I knew, I loved metal, but I mostly didn’t like rock. Metal meant precision, virtuosity, heaviness and speed. Rock (to this kind of metal fan) was simplistic, old-fashioned and (worse) commercial. Oddly, I never thought to include the very glam-oriented hair metal bands I liked in the rock camp; which I can now see is where they really belonged. I loved bands like Poison, Faster Pussycat and Pretty Boy Floyd, despite the fact that their very obvious ambition was to be famous and that they wrote schmaltzy ballads. I made the same exception, mysteriously, for Guns ‘n’ Roses, who I loved. But I thought of them as metal, not rock.

It was a distinction that my parents’ generation seemed simply not to understand. To them and their friends if you liked Metallica wasn’t that basically the same as liking Meat Loaf? But I was of the generation for whom, from the earliest days of primary school, the idea of being seen in flared trousers was the stuff of nightmares. That horror of the era we were born in was hard to let go of., which is no doubt partly why the legacy of punk was easy to embrace later. In 1988, when I first heard them, Metallica instantly became one of my favourite bands and …And Justice For All one of my favourite albums. A crucial part of that was that the band, as I first knew them, looked cool to me. When, probably later that year, I first heard Ride the Lightning and Master of Puppets I loved those too, but the sight of the great Cliff Burton (RIP) in his denim bellbottoms with his middle-parted hair and little moustache, looking like he should have been in Status Quo circa 1974 was extremely cringe-inducing; that was not cool. Not in Scotland in 1988 anyway.

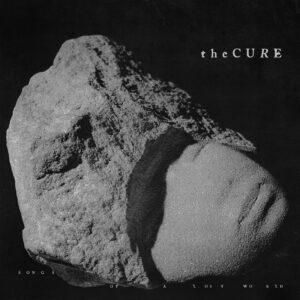

It took a while for that attitude to change. One of the gateway albums that led young teen me away from heavy metal and towards the indie/alternative world was Faith No More’s The Real Thing, which included a cover of “War Pigs.” And at that time the song still felt old fashioned and less good than the rest of the album to me. It was only after a few years of hardcore indie snobbery that my attitude really changed. As my adolescence got to the more painfully introspective stage I stopped listening to metal, having been introduced to things like the Pixies and Ride and simultaneously discovering slightly older music like The Smiths, The Cure, Joy Division and the Jesus & Mary Chain. The part of me that still liked loud and heavy guitars didn’t care so much about precision anymore and so alongside the typical UK indie stuff, I also liked grunge for a while, mainly Mudhoney, Tad and Nirvana, but especially grunge-adjacent weirdness like the Butthole Surfers and Sonic Youth. That would seem to provide an obvious bridge to the hard rock of the 70s, since virtually all grunge-oriented bands referenced Sabbath and Kiss, but no.

In fact, what happened was that in the Britpop era, I loved 70s-influenced bands like Pulp and Suede (I was never a fan of Blur or Oasis) and as Britpop became dull I started to get into the older music that Britpop referenced. At first it was mostly Bowie and Lou Reed, but after reading Shots From the Hip (referenced a million times on this website) by Charles Shaar Murray, I broadened my horizons to include 70s glam in general (Roxy Music, Eno, Jobriath, Raw Power-era Stooges, but also the bubblegum stuff) and other things that Murray mentioned, whether positively or disparagingly. The latter seems odd but I’ve discovered lots of things I like that way. And suddenly, Ozzy was inescapable (though less so than he is this week).

I bought the Charles Shaar Murray book because Bowie was featured heavily in it; but he also wrote about Black Sabbath. I bought a book by the great photographer Mick Rock, because he had photographed Bowie and Lou Reed and Iggy and John Cale; but who should be in there but Ozzy, looking uncharacteristically thoughtful. I bought old 70s music annuals from glam and tail end of glam era; Fab 208 maybe – because they had Bowie and Mott the Hoople and Pilot and whatnot in them, but inside there was also mention of Black Sabbat. I remember a paragraph about their then-forthcoming compilation We Sold Our Souls for Rock ‘n’ Roll being especially intriguing.

Anyway, one thing led to another and I spent a large chunk of the late 90s and early 2000s immersing myself in the music of the 1970s. At first it was primarily glam, but then all kinds of rock, pop, soul, funk etc. At some point it started including bands that I’d long been aware of and never liked; like Led Zeppelin, Kiss – and Black Sabbath. The first Black Sabbath album I owned was Sabotage, bought for 50 pence in a charity shop. The texture of the sleeve was, interestingly, the same texture as my LP of Joy Division’s Unknown Pleasures, but the imagery was a little less classy, thanks to Bill Ward’s checked underpants being visible through his red tights; oh well. Ozzy sounded pretty much as I remembered from “Miracle Man,” but primed by Charles Shaar Murray’s description of Ozzy [caterwauling] about something or other in a locked basement and with a more sympathetic production and – crucially – the far more bare and elemental sound of Black Sabbath, so unappealing just a few years earlier, he sounded right. And then, when I heard the earliest Black Sabbath albums, Black Sabbath and Paranoid, both from 1970, one of the things they reminded me of, most unexpectedly, was Joy Division.

Yes, the whole aura is different, Sabbath were surly and aggressive where Joy Division were solemn and withdrawn, but there’s something about the simplicity of the sound. Geezer and Hooky’s basses took up as much space as Tony and Bernard’s guitars. Bill Ward, like Stephen Morris, was a drummer who brought a strong dance/funk element into the band’s rock music without any sense of incongruity. Ozzy and Ian Curtis are worlds apart as vocalists, but both have a despairing intensity that makes them stand out, even within their respective genres. Both bands were from the grim, grey, hopeless industrial 1970s north of England, but whereas Joy Division were definitively a product of Manchester, with all the gritty coolness that conferred upon them, Sabbath were solidly of Birmingham, with all of the perceived oafishness and lack of credibility that entailed in the music press at least. Both singers were self-destructive too, but the same year that Ian Curtis tragically ended his life, Ozzy was reflecting on his self-destructive behaviour in “Suicide Solution”* and starting his life anew, launching a solo career which, against all expectations, made him an even bigger star and ultimately the icon who is being mourned today, far more widely than I’m sure he would ever have imagined. It was a good ending.

*Ozzy was always a far more thoughtful lyricist than he’s given credit for; I can’t think of any other artist from the aggressively cocky 80s hair metal scene who would have written the glumly confessional anthem “Secret Loser” from Ozzy’s 1986 album The Ultimate Sin

Because I’m a nerd, and not just a music nerd, writing this piece made me think of Michael Moorcock’s elegiac sci-fi/fantasy novel novel, The End of All Songs, published in 1976, the year that Ian Curtis, Peter Hook and Bernard Sumner met at a Sex Pistols concert in the Lesser Free Trade Hall in Manchester, the year that Black Sabbath released their seventh album, Technical Ecstasy, generally agreed to be the one where the cracks started to show in the Ozzy-led lineup but one of my favourites. Moorcock took the title of his novel from a poem by the Victorian writer Ernest Dowson, which feels appropriate to end with, since fading out is kind of a hassle, text-wise.

With pale, indifferent eyes, we sit and wait

For the drop’d curtain and the closing gate:

This is the end of all the songs man sings.

Ernest Dowson, Dregs (1899)

I loved Nechochwen’s

I loved Nechochwen’s  Ghost World have made some of my favourite albums; I was immediately smitten with their 2017 debut album, which was my

Ghost World have made some of my favourite albums; I was immediately smitten with their 2017 debut album, which was my  Hmm. I gave this a go because, despite the fact that industrial metal is one of my least favourite genres of music in the world, Swiss black metal has a special place in my heart and LADLO is a very dependable label. And..? Well, not exactly my cup of tea, but it’s good, there’s a nice chaotic, noisy atmosphere and it reminded me at times of Abigor (who I do like) and Blacklodge (who I occasionally like). The atmospheres and the choral bits are really cool and the noisy stuff with sirens etc is impressively alarming, though not nice if you have a headache.

Hmm. I gave this a go because, despite the fact that industrial metal is one of my least favourite genres of music in the world, Swiss black metal has a special place in my heart and LADLO is a very dependable label. And..? Well, not exactly my cup of tea, but it’s good, there’s a nice chaotic, noisy atmosphere and it reminded me at times of Abigor (who I do like) and Blacklodge (who I occasionally like). The atmospheres and the choral bits are really cool and the noisy stuff with sirens etc is impressively alarming, though not nice if you have a headache.

I

I

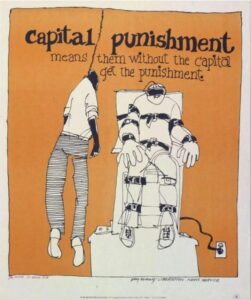

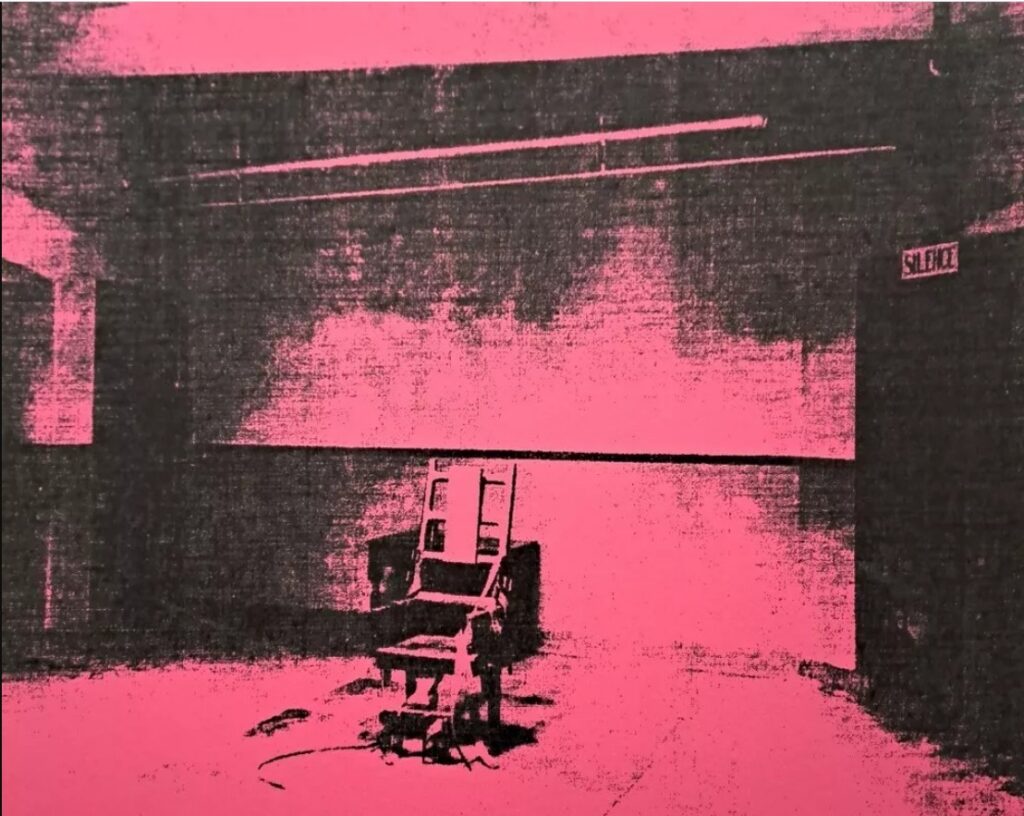

The current case of Luigi Mangione is far stranger. It’s the only time I can recall that the supporters (in this case I think ‘fans’ would be just as correct a word) of someone accused of murder want the suspect to be guilty rather than innocent. Whether they would still feel that way if he looked different or had a history of violent crime or had a different kind of political agenda is endlessly debatable, but irrelevant. It looks as if the State will be seeking the death penalty for him and for all the reasons listed above I think that’s wrong. But assuming that he’s guilty, which obviously one shouldn’t do (and if he isn’t, Jesus Christ, good luck getting a fair trial!) Mangione himself and some of his fans, should really be okay with it. If he is guilty, he hasn’t done anything to help a single person to get access to healthcare or improve the healthcare system or even effectively protested against it in a way that people with political power can positively react to. UnitedHealthcare still has a CEO, still has dubious political connections and still treats people very badly. That doesn’t mean that it’s an unassailable monolith that can never be changed, but clearly removing one figurehead isn’t how it can be done.

The current case of Luigi Mangione is far stranger. It’s the only time I can recall that the supporters (in this case I think ‘fans’ would be just as correct a word) of someone accused of murder want the suspect to be guilty rather than innocent. Whether they would still feel that way if he looked different or had a history of violent crime or had a different kind of political agenda is endlessly debatable, but irrelevant. It looks as if the State will be seeking the death penalty for him and for all the reasons listed above I think that’s wrong. But assuming that he’s guilty, which obviously one shouldn’t do (and if he isn’t, Jesus Christ, good luck getting a fair trial!) Mangione himself and some of his fans, should really be okay with it. If he is guilty, he hasn’t done anything to help a single person to get access to healthcare or improve the healthcare system or even effectively protested against it in a way that people with political power can positively react to. UnitedHealthcare still has a CEO, still has dubious political connections and still treats people very badly. That doesn’t mean that it’s an unassailable monolith that can never be changed, but clearly removing one figurehead isn’t how it can be done.

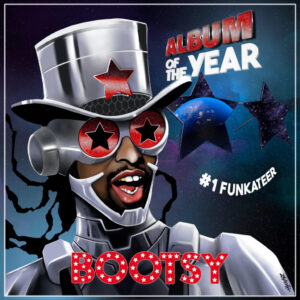

Henrik Palm – Nerd Icon (Svart Records) – sort of 80s-ish, sort of metal-ish, 100% individual

Henrik Palm – Nerd Icon (Svart Records) – sort of 80s-ish, sort of metal-ish, 100% individual Myriam Gendron – Mayday (Feeding Tube) – I loved Not So Deep as a Well ten years ago (mentioned in passing

Myriam Gendron – Mayday (Feeding Tube) – I loved Not So Deep as a Well ten years ago (mentioned in passing  Ihsahn – Ihsahn (Candlelight) – wrote about it

Ihsahn – Ihsahn (Candlelight) – wrote about it  One of my top 3 or 4 albums of all time, John Cale’s Paris 1919 was reissued this year, his latest POPtical Illusion was good too

One of my top 3 or 4 albums of all time, John Cale’s Paris 1919 was reissued this year, his latest POPtical Illusion was good too Mick Harvey – Five Ways to Say Goodbye (Mute) – lovely autumnal album by ex-Bad Seed and musical genius, more

Mick Harvey – Five Ways to Say Goodbye (Mute) – lovely autumnal album by ex-Bad Seed and musical genius, more

Aara –

Aara –  Claire Rousay –

Claire Rousay –  Alcest – Chants de L’Aurore (Nuclear Blast) – seems so long ago that I almost forgot about it, but this was (I thought) the best Alcest album for years, beautiful, wistful and generally lovely. I talked to Neige about it at the time, I should post that interview here at some point!

Alcest – Chants de L’Aurore (Nuclear Blast) – seems so long ago that I almost forgot about it, but this was (I thought) the best Alcest album for years, beautiful, wistful and generally lovely. I talked to Neige about it at the time, I should post that interview here at some point!

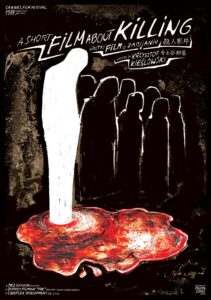

2023 was the usual mixed bag of things; I didn’t see any of the big movies of

2023 was the usual mixed bag of things; I didn’t see any of the big movies of the year yet. I have watched half of Saltburn, which so far makes me think of the early books of Martin Amis, especially Dead Babies (1975) and Success (1978) – partly because I read them again after he died last year. They are both still good/nasty/funny, especially Success, but whereas I find that having no likeable characters in a book is one thing, and doesn’t stop the book from being entertaining, watching unlikeable characters in a film is different – more like spending time with actual unlikeable people, perhaps because – especially in a film like Saltburn – you can only guess at their motivations and inner life. So, the second half of Saltburn remains unwatched – but I liked it enough that I will watch it.

the year yet. I have watched half of Saltburn, which so far makes me think of the early books of Martin Amis, especially Dead Babies (1975) and Success (1978) – partly because I read them again after he died last year. They are both still good/nasty/funny, especially Success, but whereas I find that having no likeable characters in a book is one thing, and doesn’t stop the book from being entertaining, watching unlikeable characters in a film is different – more like spending time with actual unlikeable people, perhaps because – especially in a film like Saltburn – you can only guess at their motivations and inner life. So, the second half of Saltburn remains unwatched – but I liked it enough that I will watch it.

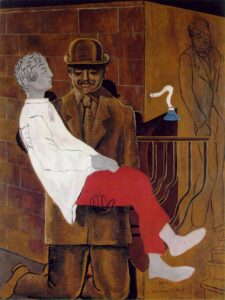

I read lots of good books in 2023 – I started keeping a list but forgot about it at some point – but the two that stand out in my memory as my favourites are both non-fiction. Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art is completely engrossing and full of exciting ways of really looking at pictures. I wrote at length about Elena Kostyuchenko’s I Love Russia

I read lots of good books in 2023 – I started keeping a list but forgot about it at some point – but the two that stand out in my memory as my favourites are both non-fiction. Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art is completely engrossing and full of exciting ways of really looking at pictures. I wrote at length about Elena Kostyuchenko’s I Love Russia  It’s no great surprise to me that my favourite books of the year would be – like much of my favourite art – by women. Though I think the individual voice is crucial in all of the arts, individuals don’t grow in a vacuum and because female (and, more widely, non-male) voices and viewpoints have always been overlooked, excluded, marginalised and/or patronised, women and those outside of the standard, traditional male authority figures more generally, tend to have more interesting and insightful perspectives than the ‘industry standard’ artist or commentator does. The first time that thought really struck me was when I was a student, reading about Berlin Dada and finding that Hannah Höch was obviously a much more interesting and articulate artist than (though I love his work too) her partner Raoul Hausmann, but that Hausmann had always occupied a position of authority and a reputation as an innovator, where she had little-to-none. And the more you look the more you see examples of the same thing. In fact, because women occupied – and in many ways still occupy – more culturally precarious positions than men, that position informs their work – thinking for example of artists like Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage or – a bigger name now – Frida Kahlo – giving it layers of meaning inaccessible to – because unexperienced by – their male peers.

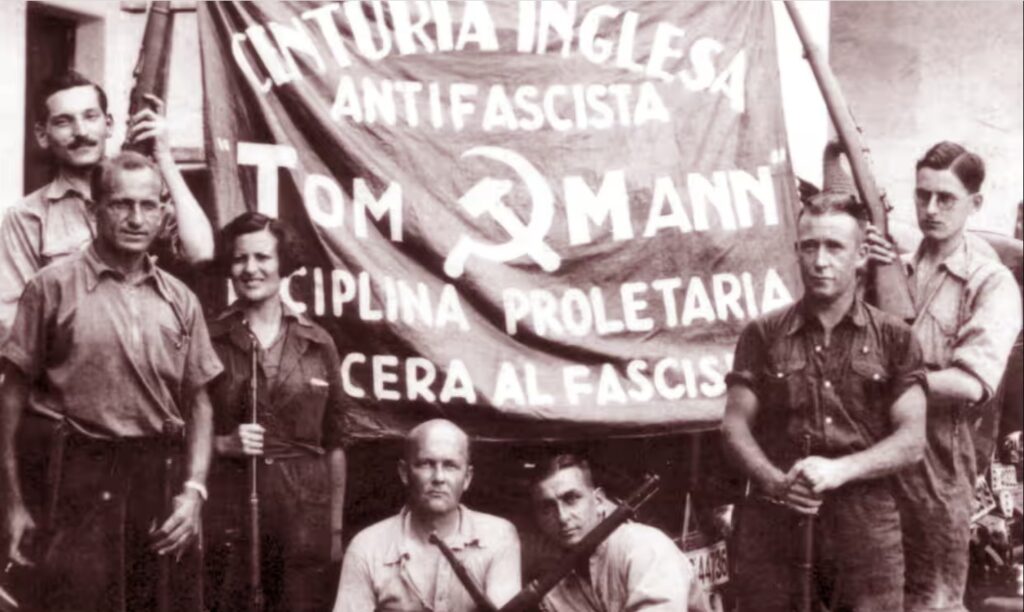

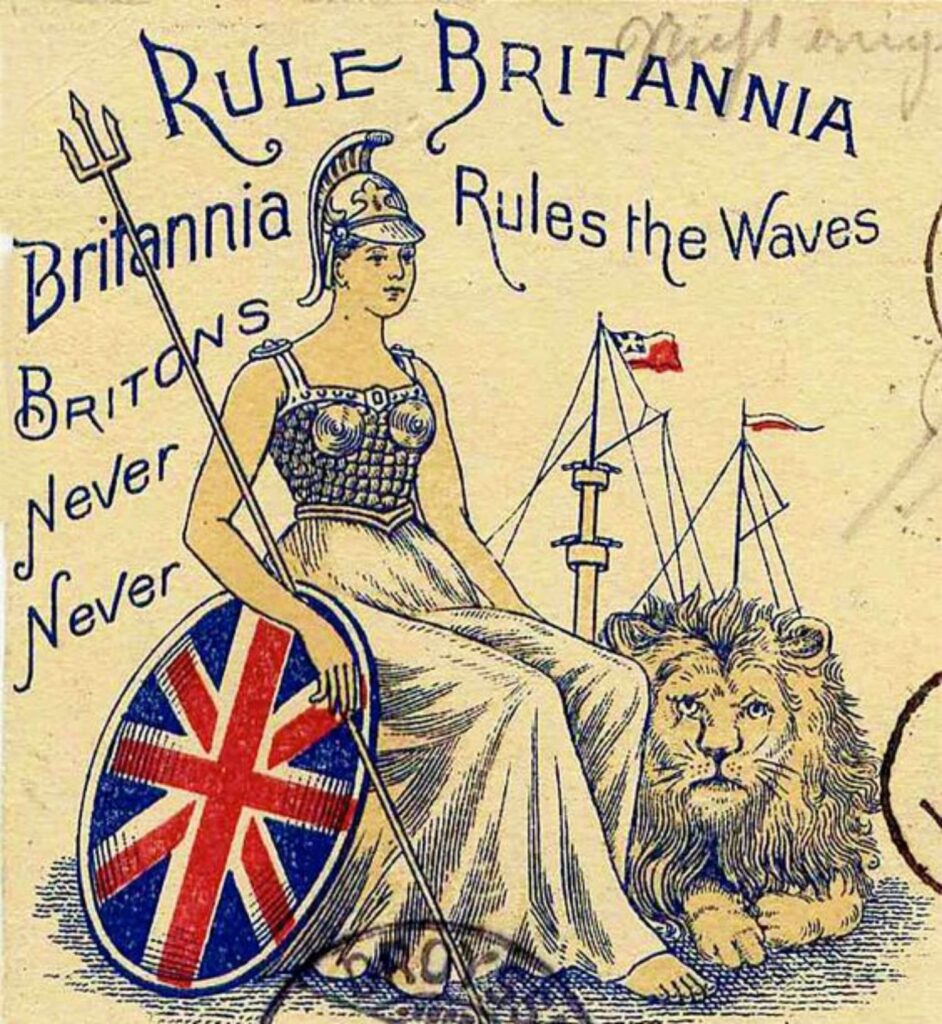

It’s no great surprise to me that my favourite books of the year would be – like much of my favourite art – by women. Though I think the individual voice is crucial in all of the arts, individuals don’t grow in a vacuum and because female (and, more widely, non-male) voices and viewpoints have always been overlooked, excluded, marginalised and/or patronised, women and those outside of the standard, traditional male authority figures more generally, tend to have more interesting and insightful perspectives than the ‘industry standard’ artist or commentator does. The first time that thought really struck me was when I was a student, reading about Berlin Dada and finding that Hannah Höch was obviously a much more interesting and articulate artist than (though I love his work too) her partner Raoul Hausmann, but that Hausmann had always occupied a position of authority and a reputation as an innovator, where she had little-to-none. And the more you look the more you see examples of the same thing. In fact, because women occupied – and in many ways still occupy – more culturally precarious positions than men, that position informs their work – thinking for example of artists like Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage or – a bigger name now – Frida Kahlo – giving it layers of meaning inaccessible to – because unexperienced by – their male peers. If that backlash comes, it will be from the academic equivalent of those figures who, in 2023 continued to dominate the cultural landscape. These are conservative (even if theoretically radical) people who pride themselves on their superior rational, unsentimental and “common sense” outlook, but whose views tend to have a surprising amount in common with some of the more wayward religious cults. Subscribing to shallowly Darwinist ideas, but only insofar as they reinforce one’s own prejudices and somehow never feeling the need to follow them to their logical conclusions is not new, but it’s very now. Underlying ideas like the ‘survival of the fittest’, which then leads to the more malevolent idea of discouraging the “weak” in society by abolishing any kind of social structure that might support them is classic conservatism in an almost 19th century way, but somehow it’s not surprising to see these views gaining traction in the discourse of the apparently futuristic world of technology. In more that one way, these kinds of traditionalist, rigidly binary political and social philosophies work exactly like religious cults, with their apparently arbitrary cut off points for when it was that progress peaked/halted and civilisation turned bad. That point varies; but to believe things were once good but are now bad must always be problematic, because when, by any objective standards, was everything good, or were even most things good? For a certain class of British politician that point seems to have been World War Two, which kind of requires one to ignore actual World War Two. But the whole of history is infected by this kind of thinking – hence strange, disingenuous debates about how bad/how normal Empite, colonialism or slavery were; incidentially, you don’t even need to read the words of abolitionists or slaves themselves (though both would be good to read) to gain a perspective of whether or not slavery was considered ‘normal’ or bad by the standards of the time. Just look at the lyrics to Britain’s most celebratory, triumphalist song of the 18th century, Rule Britannia. James Thomson didn’t write “Britons never, never, never shall be slaves; though there’s nothing inherently wrong with slavery.” They knew it was something shameful, something to be dreaded, even while celebrating it.

If that backlash comes, it will be from the academic equivalent of those figures who, in 2023 continued to dominate the cultural landscape. These are conservative (even if theoretically radical) people who pride themselves on their superior rational, unsentimental and “common sense” outlook, but whose views tend to have a surprising amount in common with some of the more wayward religious cults. Subscribing to shallowly Darwinist ideas, but only insofar as they reinforce one’s own prejudices and somehow never feeling the need to follow them to their logical conclusions is not new, but it’s very now. Underlying ideas like the ‘survival of the fittest’, which then leads to the more malevolent idea of discouraging the “weak” in society by abolishing any kind of social structure that might support them is classic conservatism in an almost 19th century way, but somehow it’s not surprising to see these views gaining traction in the discourse of the apparently futuristic world of technology. In more that one way, these kinds of traditionalist, rigidly binary political and social philosophies work exactly like religious cults, with their apparently arbitrary cut off points for when it was that progress peaked/halted and civilisation turned bad. That point varies; but to believe things were once good but are now bad must always be problematic, because when, by any objective standards, was everything good, or were even most things good? For a certain class of British politician that point seems to have been World War Two, which kind of requires one to ignore actual World War Two. But the whole of history is infected by this kind of thinking – hence strange, disingenuous debates about how bad/how normal Empite, colonialism or slavery were; incidentially, you don’t even need to read the words of abolitionists or slaves themselves (though both would be good to read) to gain a perspective of whether or not slavery was considered ‘normal’ or bad by the standards of the time. Just look at the lyrics to Britain’s most celebratory, triumphalist song of the 18th century, Rule Britannia. James Thomson didn’t write “Britons never, never, never shall be slaves; though there’s nothing inherently wrong with slavery.” They knew it was something shameful, something to be dreaded, even while celebrating it.

My favourite album of that year was Ihsahn’s Das Seelenbrechen, and it’s still one of my favourite albums. I rarely listen to it all the way through at the moment, but various tracks, such as Pulse, Regen and NaCL are still in regular rotation

My favourite album of that year was Ihsahn’s Das Seelenbrechen, and it’s still one of my favourite albums. I rarely listen to it all the way through at the moment, but various tracks, such as Pulse, Regen and NaCL are still in regular rotation My favourite album of 2014 was

My favourite album of 2014 was My album of 2015 was Life is a Struggle, Give Up by

My album of 2015 was Life is a Struggle, Give Up by

I wouldn’t necessarily say I was aware of it at the time, but 2016 was a great year for music. My album of the year was Wyatt at the Coyote Palace by Kristin Hersh (which I enthused about

I wouldn’t necessarily say I was aware of it at the time, but 2016 was a great year for music. My album of the year was Wyatt at the Coyote Palace by Kristin Hersh (which I enthused about

2017 had fewer standouts for me but my album of the year, the self-titled debut by Finnish alt-rock band Ghost World, which I wrote enthusiastically about

2017 had fewer standouts for me but my album of the year, the self-titled debut by Finnish alt-rock band Ghost World, which I wrote enthusiastically about  I was hugely surprised in 2018 to find that my album of the year was an electronic one,

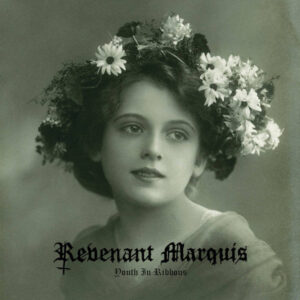

I was hugely surprised in 2018 to find that my album of the year was an electronic one,  In 2019, I loved another Collectress album, Different Geographies but it didn’t replace or match Mondegreen in my affections. I can’t seem to find my album of the year strangely, but it might well have been Youth in Ribbons by Revenant Marquis, still my favourite of that prolific artist’s releases.

In 2019, I loved another Collectress album, Different Geographies but it didn’t replace or match Mondegreen in my affections. I can’t seem to find my album of the year strangely, but it might well have been Youth in Ribbons by Revenant Marquis, still my favourite of that prolific artist’s releases.