an annoying but perhaps necessary note; “Alan (or Allan, or Allen) Smithee” is a pseudonym used by Hollywood film directors when they wish to disown a project

Watch out, this starts off being insultingly elementary, but then gets complicated and probably contradictory, quite quickly.

Countries, States and religions are not monoliths and nor are they sentient. They don’t have feelings, aims, motivations or opinions. So whatever is happening in the Middle East isn’t ‘Judaism versus Islam’ or even ‘Israel versus Palestine’, any more than “the Troubles”* were/are ‘Protestantism versus Catholicism’ or ‘Britain versus Ireland’.

* a euphemism, which, like most names for these things is partly a method of avoiding blame – as we’ll see

Places and atrocities aren’t monoliths either; Srebrenica didn’t massacre anybody**, the Falkland islands didn’t have a conflict, ‘the Gulf’ didn’t have any wars and neither did Vietnam or Korea. But somebody did. As with Kiefer Sutherland and Woman Wanted in 1999 or Michael Gottlieb and The Shrimp on the Barbie in 1990 and whoever it was that directed Gypsy Angels in 1980, nobody wants to claim these wars afterwards. But while these directors have the handy pseudonym Allan Smithee to use, there is no warmongering equivalent, and so what we get is geography, or flatly descriptive terms like ‘World War One’, which divert the focus from the aggressor(s) and only the occasional exception (The American War of Independence) that even references the real point of the war. But, whether interfered with by the studio or not, Kevin Yagher did direct Hellraiser: Bloodline, just as certain individuals really are responsible for actions which are killing human beings as you read this. Language and the academic study of history will probably help to keep their names quiet as events turn from current affairs and into history. Often this evasion happens for purely utilitarian reasons, perhaps even unknowingly, but sometimes it is more sinister.

** see?

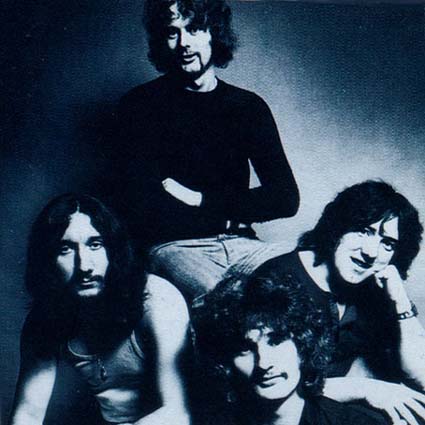

As the 60s drew to its messy end, the great Terry “Geezer” Butler wrote lines which, despite the unfortunate repeat/rhyme in the first lines, have a Blakean power and truth:

Generals gathered in their masses

Just like witches at black massesBlack Sabbath, War Pigs, 1970

There is something sinister and even uncanny in the workings of power, in the distance between avowed and the underlying motivations behind military action. Power politics feels like it is – possibly because intuitively it seems like it should be – cold and logical, rather than human and emotional. It doesn’t take much consideration though to realise that even beneath the chilly, calculated actions of power blocs there are weird and strangely random human desires and opinions, often tied in with personal prestige, which somehow seems to that person to be more important than not killing people or not having people killed.

Anyway, Geezer went on to say:

Politicians hide themselves away

They only started the war

Why should they go out to fight?

They leave that role to the poorStill Black Sabbath, War Pigs (1970)

And that’s right too; but does that mean Butler’s ‘poor’ should take no responsibility at all for their actions? In the largest sense they are not to blame for war or at least for the outbreak of war; and conscripts and draftees are clearly a different class again from those who choose to “go out to fight.” But. As so often WW2 is perhaps the most extreme and therefore the easiest place to find examples; whatever his orders or reasons, the Nazi soldier (and there were lots of them) who shot a child and threw them in a pit, actually did shoot a child and throw them in a pit. His immediate superior may have done so too, but not to that particular child. And neither did Himmler or Adolf Hitler. Personal responsibility is an important thing, but responsibility, especially in war, isn’t just one act and one person. Between the originator and the architects of The Final Solution and the shooter of that one individual child there is a chain of people, any one of whom could have disrupted that chain and even if only to a tiny degree, affected the outcome. And that tiny degree may have meant that that child, that human being, lived or died. A small thing in a death toll of something over 6 million people; unless you happen to be that person, or related to that person.

As with the naming of wars and atrocities, terms like “genocide” and “the Holocaust” are useful, especially if we want – as we clearly do – to have some kind of coherent, understandable narrative that can be taught and remembered as history. But in their grim way, these are still euphemisms. The term ‘the Holocaust’ memorialises the countless – actually not countless, but still, nearly 80 years later, being counted – victims of the Nazis’ programme of extermination. But the term also makes the Holocaust sound like an event, rather than a process spread out over the best part of a decade, requiring the participation of probably thousands of people who exercised – not without some form of coercion perhaps, but still – their free will in that participation. The Jewish scholar Hillel the Elder’s famous saying, whosoever saves a life, it is as though he had saved the entire world is hard to argue with, insofar as the world only exists for us within our perceptions. Even the knowledge that it is a spinning lump of inorganic and organic matter in space, and that other people populate it who might see it differently only exists in our perceptions. Or at least try to prove otherwise. And so the converse of Hillel’s saying – which is actually included in it but far less often quoted – is Whosoever destroys one soul, it is as though he had destroyed the entire world. Which sounds like an argument for pacifism, but while pacifism is entirely viable and valuable on an individual basis as an exercise of one’s free will* – and on occasion has a real positive effect – one-sided pacifism relies on its opponents not taking a cynically Darwinian approach, which is hopeful at best. Pacifism can only really work if everyone is a pacifist, and everyone isn’t a pacifist.

*the lone pacifist can at least say, ‘these terrible things happened, but I took no part in them’, which is something, especially if they used what peaceful means they could to prevent those terrible things and didn’t unwittingly contribute to the sum total of suffering; but those are murky waters to wade in.

But complicated though it all is, people are to blame for things that happen. Just who to blame is more complicated – more complicated at least than the workable study of history can afford to admit. While countries and religions are useful as misleading, straw man scapegoats, even the more manageable unit of a government is, on close examination, surprisingly hard to pin down. Whereas (the eternally handy example of) Hitler’s Nazi Party or Stalin’s Council of People’s Commissars routinely purged heretics, non-believers and dissidents, thus acting as a genuine, effective focus for their ideologies and therefore for blame and responsibility, most political parties allow for a certain amount of debate and flexibility and therefore blame-deniability. Regardless, when a party delivers a policy, every member of that party is responsible for it, or should publicly recuse themselves from it if they aren’t.

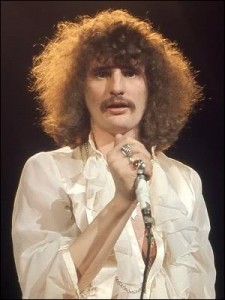

The great (indeed Sensational) Scottish singer Alex Harvey said a lot of perceptive things, not least and “[Something] I learned from studying history. Nobody ever won a war. A hundred thousand dead at Waterloo*. No glory in that. Nobody needs that.” Nobody ever won a war; but plenty of people, on both sides of every conflict, have lost one – and, as the simple existence of a second world war attests, many, many people have lost a peace too.

*Modern estimates put it at ‘only’ 11,000 plus another 40,000 or so casualties; but his point stands

But the “causes” of war are at once easily traced and extremely slippery. Actions like the 1939 invasion of Poland by the armies of Germany and the USSR were, as military actions still are, the will of certain individuals, agreed to by other individuals and then acted upon accordingly. You may or may not agree with the actions of your government or the leaders of your faith. You may even have had some say in them, but in most cases you probably haven’t. Some of those dead on the fields of Waterloo were no doubt enthusiastic about their cause, some probably less so. But very few would have had much say in the decisions which took them to Belgium in the first place.

The buck should stop with every person responsible for wars, crimes, atrocities; but just because that’s obviously impossible to record – and even if it wasn’t, too complex to write in a simple narrative – that doesn’t mean the buck should simply not stop anywhere. Victory being written by the winners often means that guilt is assigned to the losers, but even when that seems fair enough (there really wouldn’t have been a World War Two without Hitler) it’s a simplification (there wouldn’t have been an effective Hitler without the assistance of German industrialists) and a one-sided one (it was a World War because most of the leading participants had already had unprovoked wars of conquest). That was a long sentence. But, does the disgusting history of Western colonialism, the arguably shameful treatment of Germany by the Allies after WW1 and the dubious nature of the allies and some of their actions make Hitler himself any less personally responsible for the war? And does Hitler’s own guilt make the soldier who shoots a child or unarmed adult civilians, or the airman who drops bombs on them any less responsible for their own actions?

Again; only human beings do these things, so the least we can do is not act like they are some kind of unfathomable act of nature when we discuss them or name them. Here’s Alex Harvey again; “Whether you like it or not, anybody who’s involved in rock and roll is involved in politics. Anything that involves a big crowd of people listening to what you say is politics.” If rock and roll is politics, then actual politics is politics squared; and for as long as we settle, however grudgingly or complacently, for pyramidal power structures for our societies then the person at the top of that pyramid, enjoying its vistas and rarefied air should be the one to bear its most sombre responsibilities. But all who enable the pyramid to remain standing should accept their share of it too.

So when you’re helplessly watching something that seems like an unbelievable waste of people’s lives and abilities, pay close attention to who’s doing and saying what, even if you don’t want to, because the credits at the end probably won’t tell you who’s really responsible.

A foolish name, you might think; and yet there have been no less than three different bands called Funeral Bitch. This is the first and best of the three, the one formed by Paul Speckmann in 1986-8 between different incarnations of the much better known Master. Funeral Bitch were much in the same vein; extremely fast and rough (though still anthemic) death/thrash, with Speckmann’s hoarse bellowing a bit too prominent in the thin mix. That said, the demos are imbued with a real raw vitality that could arguably have been lost with the kind of production favoured by the big-name thrash bands of the era. It’s a real time capsule of the more extreme end of the 80s thrash scene and there’s a fair amount of intentional silliness too; a key but often forgotten feature of era. Interestingly, the guitarist is Alex Olvera, better known for his tenure as bassist with mid-level speed metal band Znöwhite around the same time. Only essential for Master fans, but generally fun, even if the live tracks are (appropriately) ‘rough as guts’ as they say down under.

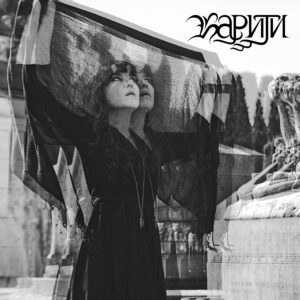

A foolish name, you might think; and yet there have been no less than three different bands called Funeral Bitch. This is the first and best of the three, the one formed by Paul Speckmann in 1986-8 between different incarnations of the much better known Master. Funeral Bitch were much in the same vein; extremely fast and rough (though still anthemic) death/thrash, with Speckmann’s hoarse bellowing a bit too prominent in the thin mix. That said, the demos are imbued with a real raw vitality that could arguably have been lost with the kind of production favoured by the big-name thrash bands of the era. It’s a real time capsule of the more extreme end of the 80s thrash scene and there’s a fair amount of intentional silliness too; a key but often forgotten feature of era. Interestingly, the guitarist is Alex Olvera, better known for his tenure as bassist with mid-level speed metal band Znöwhite around the same time. Only essential for Master fans, but generally fun, even if the live tracks are (appropriately) ‘rough as guts’ as they say down under. Kariti is a Russian-Italian singer of dark folk music and, after an extremely peculiar and archaic-sounding voices-only intro, Covered Mirrors becomes an album of moody semi-acoustic songs which are not especially folk-sounding, but are very pretty indeed. The guitar sound is crisp and almost tangible, and the vocals (mainly in English) are clear and mournful, as befits the album’s themes of ‘death and parting’. It’s a beautifully grave and austere record, with an intimate quality that (especially through headphones) brings the listener extremely close to the performance, while remaining emotionally remote and unreachable: a perfect album for a time of quarantine, if not one that will cheer anyone up.

Kariti is a Russian-Italian singer of dark folk music and, after an extremely peculiar and archaic-sounding voices-only intro, Covered Mirrors becomes an album of moody semi-acoustic songs which are not especially folk-sounding, but are very pretty indeed. The guitar sound is crisp and almost tangible, and the vocals (mainly in English) are clear and mournful, as befits the album’s themes of ‘death and parting’. It’s a beautifully grave and austere record, with an intimate quality that (especially through headphones) brings the listener extremely close to the performance, while remaining emotionally remote and unreachable: a perfect album for a time of quarantine, if not one that will cheer anyone up. Alternately really great and very silly indeed, the sci-fi theme/concept behind Space Goretex sometimes gets in the way of the music. At its best the marriage of the unusual (but mostly surprisingly low key) musical textures of

Alternately really great and very silly indeed, the sci-fi theme/concept behind Space Goretex sometimes gets in the way of the music. At its best the marriage of the unusual (but mostly surprisingly low key) musical textures of  Always a surprise to find that non-mainstream musicians still release singles, but that’s what Manes are doing; and, like their last album, the superb Slow Motion Death Sequence it’s black metal in feeling only; musically the title track is a kind of eccentric and brooding widescreen gothic rock (I guess; it reminded me a bit of the Planet Caravan type early Black Sabbath ballads and musically but definitely not vocally a little bit of Fields of the Nephilim; there’s no electronic element on this one). It’s beautifully recorded, the title track warm and limpid but with an undertone of unease that builds throughout. The B side (is that still what it is for a digital release?) is Mouth of the Volcano, an atmospheric doomy semi-electronic chug built around a strangely familiar spoken word section that can’t place and featuring Asgeir Hatlan (last heard in Manes on 2014’s Be All, End All) and some spooky Diamanda Galas-ish vocals from Anna Murphy (ex-Eluveitie) and Ana Carolina Skaret. An unsettling but very listenable pair of songs and so a single worth releasing; and with beautiful artwork too.

Always a surprise to find that non-mainstream musicians still release singles, but that’s what Manes are doing; and, like their last album, the superb Slow Motion Death Sequence it’s black metal in feeling only; musically the title track is a kind of eccentric and brooding widescreen gothic rock (I guess; it reminded me a bit of the Planet Caravan type early Black Sabbath ballads and musically but definitely not vocally a little bit of Fields of the Nephilim; there’s no electronic element on this one). It’s beautifully recorded, the title track warm and limpid but with an undertone of unease that builds throughout. The B side (is that still what it is for a digital release?) is Mouth of the Volcano, an atmospheric doomy semi-electronic chug built around a strangely familiar spoken word section that can’t place and featuring Asgeir Hatlan (last heard in Manes on 2014’s Be All, End All) and some spooky Diamanda Galas-ish vocals from Anna Murphy (ex-Eluveitie) and Ana Carolina Skaret. An unsettling but very listenable pair of songs and so a single worth releasing; and with beautiful artwork too. More solemn, downbeat but mostly very pretty music. I had never heard Midwife (the solo project of Madeline Johnston) before; on this album at least, it’s a bare, guitar-based sound with some ambient electronic elements, sort of shoegaze-y but not. The nearest comparison I can think of (not that anyone asked for one) is Codeine circa Frigid Stars. Forever was inspired by the unexpected loss of a friend and the music is as fragile and mournful as you’d expect. The sound is warm, clear and intimate-sounding – aside from the vocals, which are distanced by a strange spacey, reverb effect; perhaps for the best as the raw emotion is rendered slightly remote and universal, rather than immediate and personal. It’s clearly not an album for all moods: although the closing track S.W.I.M. speeds up to a Jesus and Mary Chain-esque plod, Forever is consistently slow and elegiac and nothing really lifts it out of its furrow of sadness: but beautiful for all that.

More solemn, downbeat but mostly very pretty music. I had never heard Midwife (the solo project of Madeline Johnston) before; on this album at least, it’s a bare, guitar-based sound with some ambient electronic elements, sort of shoegaze-y but not. The nearest comparison I can think of (not that anyone asked for one) is Codeine circa Frigid Stars. Forever was inspired by the unexpected loss of a friend and the music is as fragile and mournful as you’d expect. The sound is warm, clear and intimate-sounding – aside from the vocals, which are distanced by a strange spacey, reverb effect; perhaps for the best as the raw emotion is rendered slightly remote and universal, rather than immediate and personal. It’s clearly not an album for all moods: although the closing track S.W.I.M. speeds up to a Jesus and Mary Chain-esque plod, Forever is consistently slow and elegiac and nothing really lifts it out of its furrow of sadness: but beautiful for all that. More black metal, this time from Iceland. Pretty standard (in a good way), polished but not symphonic black metal, modern but very much influenced by the classic Scandinavian bands (maybe more the second-and-a-half wave, like Kampfar than the classic Mayhem-Darkthrone-Burzum axis) it’s all very well put together and has plenty of muscle and melody. Two things save it from just being yet more (and there is a lot of it) proficient ‘grim & frostbitten’ black metal – firstly, some strange and very Icelandic anthemic moments; I say very Icelandic only because those moments remind me a bit of some of the epic, windswept bits in Solstafir’s music. Although recommended by the label for fans of fellow Icelanders Misþyrming, Nyrst, though inhabiting more or less the same kind of sub-genre, definitely have their own sound and style. (I highly recommend Misþyrming’s

More black metal, this time from Iceland. Pretty standard (in a good way), polished but not symphonic black metal, modern but very much influenced by the classic Scandinavian bands (maybe more the second-and-a-half wave, like Kampfar than the classic Mayhem-Darkthrone-Burzum axis) it’s all very well put together and has plenty of muscle and melody. Two things save it from just being yet more (and there is a lot of it) proficient ‘grim & frostbitten’ black metal – firstly, some strange and very Icelandic anthemic moments; I say very Icelandic only because those moments remind me a bit of some of the epic, windswept bits in Solstafir’s music. Although recommended by the label for fans of fellow Icelanders Misþyrming, Nyrst, though inhabiting more or less the same kind of sub-genre, definitely have their own sound and style. (I highly recommend Misþyrming’s  And another one-woman folk project. Ols (Polish singer and multi-instrumentalist Anna Maria Oskierko) is very different from Kariti though, and Widma is a primitive, ritualistic sounding album with none of Covered Mirrors‘s accessible, almost pop sheen. Widma does sound traditional, but it’s more akin to Wardruna and the archaeological end of pagan folk music than the glossy Clannad-ish kind recently heard on the latest Myrkur album. This is, by contrast, pleasantly droning and primal (and in that respect reminds me of an album I bought via MySpace many years ago by

And another one-woman folk project. Ols (Polish singer and multi-instrumentalist Anna Maria Oskierko) is very different from Kariti though, and Widma is a primitive, ritualistic sounding album with none of Covered Mirrors‘s accessible, almost pop sheen. Widma does sound traditional, but it’s more akin to Wardruna and the archaeological end of pagan folk music than the glossy Clannad-ish kind recently heard on the latest Myrkur album. This is, by contrast, pleasantly droning and primal (and in that respect reminds me of an album I bought via MySpace many years ago by  A contrast to everything else here, Norwegian collective Weserbergland’s second album consists of one 42 minute track, but it’s not the krautrock–influenced prog of their Can/Tangerine Dream-flavoured debut. Instead, it’s a chaotic but weirdly coherent kind of collage which consists of performances on conventional-ish instruments: guitar/strings/sax/turntables, cut up, messed about with and reassembled into a kind of melancholy, cinematic symphony. The strange, unpredictable stuttering percussion seems like it should disrupt the flow of the piece, but somehow the jerkiness becomes part of the mood and it all flows perfectly, if not in a straight line. It’s really not like anything else I’ve heard, but reminds me a little of Masahiko Satoh and the Soundbreakers’ 1971 classic avant-garde jazz-prog-whatever album Amalgamation in its sheer ear-defeating unclassifiable-ness. I’m sure it won’t go down in history as such, but this may be a definitively 2020 release.

A contrast to everything else here, Norwegian collective Weserbergland’s second album consists of one 42 minute track, but it’s not the krautrock–influenced prog of their Can/Tangerine Dream-flavoured debut. Instead, it’s a chaotic but weirdly coherent kind of collage which consists of performances on conventional-ish instruments: guitar/strings/sax/turntables, cut up, messed about with and reassembled into a kind of melancholy, cinematic symphony. The strange, unpredictable stuttering percussion seems like it should disrupt the flow of the piece, but somehow the jerkiness becomes part of the mood and it all flows perfectly, if not in a straight line. It’s really not like anything else I’ve heard, but reminds me a little of Masahiko Satoh and the Soundbreakers’ 1971 classic avant-garde jazz-prog-whatever album Amalgamation in its sheer ear-defeating unclassifiable-ness. I’m sure it won’t go down in history as such, but this may be a definitively 2020 release.

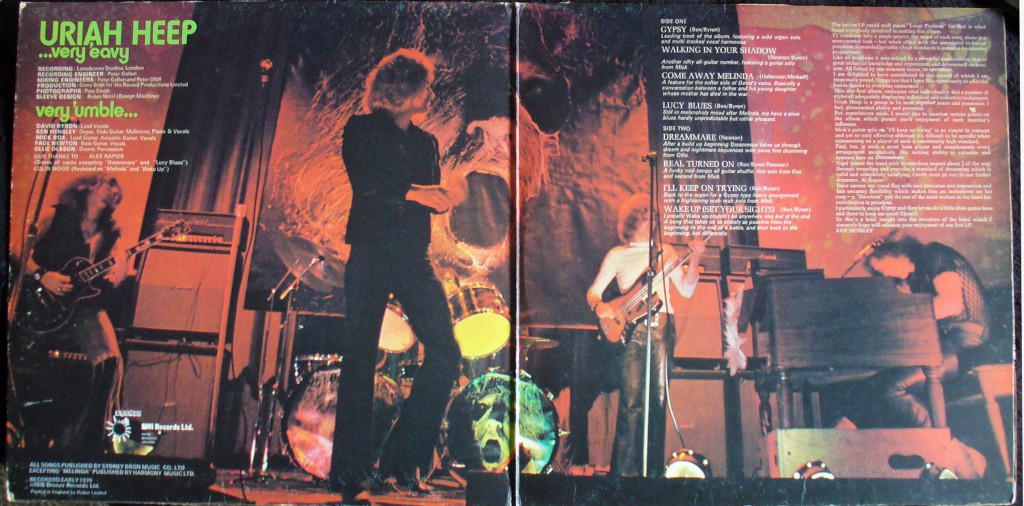

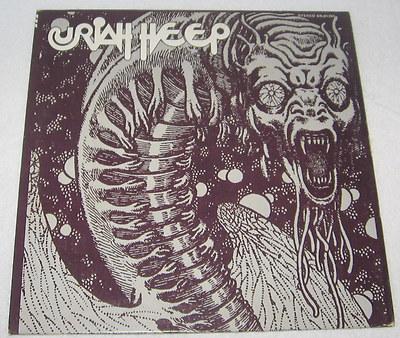

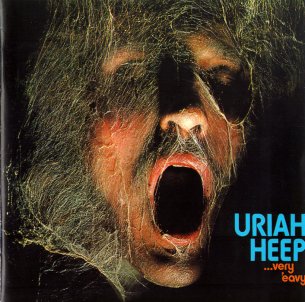

As if all this wasn’t enough, the album is housed in one of the great rock sleeves of the era: a fallen warrior (David Byron in fact) covered in cobwebs, the darkness surrounding him only broken by the (superbly-fonted) logo and title. The gatefold features a photo of the band onstage.

As if all this wasn’t enough, the album is housed in one of the great rock sleeves of the era: a fallen warrior (David Byron in fact) covered in cobwebs, the darkness surrounding him only broken by the (superbly-fonted) logo and title. The gatefold features a photo of the band onstage.