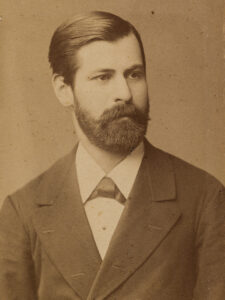

Whether or not you agree with Sigmund Freud that “the dream proves to be the first of a series of abnormal psychic formations” or that “one who cannot explain the origin of the dream pictures will strive in vain to understand [the] phobias, the obsessive and delusional ideas and likewise their therapeutic importance,” (The Interpretation of Dreams, 1913 translated by A.A. Brill) dreams are a regular, if not daily/nightly part of human life regardless of culture, language, age etc, and so not without significance. I could go on about dreams like I did about honey in a previous post but I won’t – they are too pervasive popular culture – just everywhere in culture, in books, and plays and art and films and songs (Dreams they complicate/complement my life, as Michael Stipe wrote.) That’s enough of that.

But what about daydreams? If dreams arrive uninvited from the unconscious or subconscious mind, then surely the things we think about, or dwell on, deliberately are even more important. “Dwell on” is an interesting phrase – to dwell is “to live in a place or in a particular way” BUT ‘dwell’ has a fascinating history that makes it seem like exactly the right word in this situation – from the Old English dwellan “to lead into error, deceive, mislead,” related to dwelian “to be led into error, go wrong in belief or judgment” etc, etc, according to etymonline.com : I’ll put the whole of this in a footnote* because I think it’s fascinating, but the key point is that at some time in the medieval period it’s largely negative connotations, to “delay” become modified to mean “to stay.” But I like to think the old meaning of the word lingers in the subtext like dreams in the subconscious.

But I could say something similar about my own use of the word “deliberately” above (“Things we dwell on deliberately”) and even more so the phrase I nearly used instead, which was “on purpose” – but then this would become a ridiculously long and convoluted piece of writing, so that’s enough etymology for now.

The human mind is a powerful thing. Even for those of us who don’t believe in telekinesis or remote viewing or ‘psychic powers’ in the explicitly paranormal sense. After all, your mind controls everything you think and nearly everything you do to the point where separating the mind from the body, as western culture tends to do, becomes almost untenable. Even though the euphemism “unresponsive wakefulness syndrome” has gained some traction in recent years, that’s because the dysphemism (had to look that word up) “persistent vegetative state” is something we fear and therefore that loss of self, or of humanity offends us. It’s preferable for most of us, as fiction frequently demonstrates, to believe that even in that state, dreams of some kind continue in the mind; because as human beings we are fully our mind in a way that we are only occasionally fully our body. One of the fears connected to the loss of self is that we lose the ability to choose what to think about, which is intriguing because that takes us again into the (might as well use the pompous word) realm of dreams.

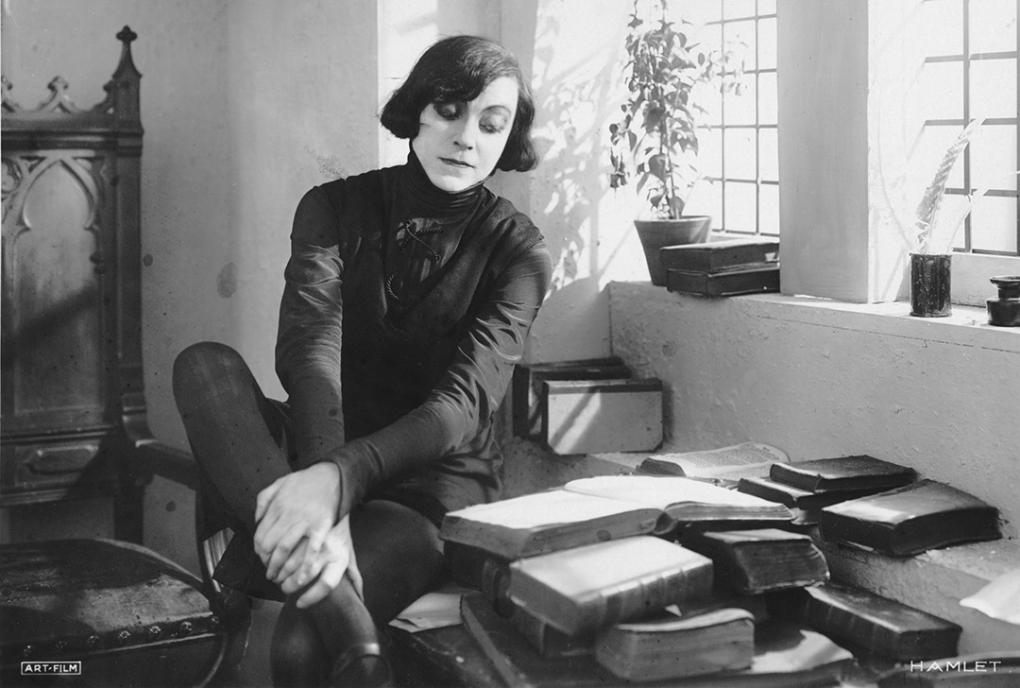

My favourite Shakespeare quote is the last line from this scene in Hamlet (Act 2 Scene 2)

Hamlet: Denmark’s a prison.

Rosencrantz: Then is the world one.

Hamlet: A goodly one, in which there are many confines, wards, and

dungeons, Denmark being one o’ th’ worst.

Rosencrantz: We think not so, my lord.

Hamlet: Why then ’tis none to you; for there is nothing either good or

bad, but thinking makes it so. To me it is a prison.

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so” seems to deny any possibility of objective morality, but its logic is undeniable. After all, you or I may think that [insert one of thousands of examples from current politics and world events] is ‘wrong’, but if [individual in position of power] doesn’t think so, and does the wrong thing, even if all of the worst possible outcomes stem from it, the most you can say is that you, and people who agree with you, think it was wrong. Hitler almost certainly believed, as he went to the grave, that he was a martyr who had failed in his grand plan only because of the betrayal and duplicity of others. I think that’s wrong, you hopefully think that’s wrong, even “history” thinks that’s wrong, but none of that matters to Hitler in his bunker in 1945, any more than Rosencrantz & Guildenstern finding Denmark to be a nice place if only their old friend Hamlet could regain his usual good humour makes any difference to Hamlet.

Anyway, daydreams or reveries (a nice word that feels a bit pretentious to say); its dictionary definitions are mostly very positive – a series of pleasant thoughts about something you would prefer to be doing or something you would like to achieve in the future.

A state of abstracted musing.

A loose or irregular train of thought occurring in musing or mediation; deep musing – and there’s a school of thought that has been around for a long time but seems even more prevalent today, which values daydreams as, not just idle thoughts, but as affirmations. Anyone who has tried to change their life through hypnosis or various kinds of therapy will find that daydreaming and visualising are supposed to be important aspects of your journey to a better you. In a way all of these self-help gurus, lifestyle coaches and therapists are saying the same thing; as Oscar Hammerstein put it, “You got to have a dream,

If you don’t have a dream, How you gonna have a dream come true?” But is making your dreams, even your daydreams, come true necessarily a good thing?

I seem to remember once reading that if you can focus all of your attention on something for 15 seconds you’ll remember it forever (not sure about the duration; if you Google stuff like this you find there are millions of people offering strategies to improve your memory, which isn’t quite what I was looking for). Whether or not that’s true, every time I see a vapour trail in an otherwise blue sky, I have the same thought/image – actually two thoughts, but “first you look so strong/then you fade away” came later and failed to replace the earlier thought, which must date from the age of 9 or 10 or so. I realise that people telling you their dreams is boring (or so people say, I never find it to be so), but you don’t have to keep reading. I can see the fluffy, white trail against the hot pale blue sky (it’s summer, the sun is incandescent and there are no clouds) and as my eye follows it from its fraying, fading tail to its source, I can see the nose cone of the plane glinting in the sun, black or red and metallic. It looks slow, leisurely even, but the object is travelling at hundreds of miles an hour. I know there’s no pilot inside that warm, clean shell (I can imagine feeling its heat, like putting your hand on the bonnet or roof of a car parked in direct sunshine; only there are rivets studding the surface of this machine). I’m shading my eyes with my hand, watching its somehow benign-looking progress, but I know that it’s on its way to the nearby airforce base and that others are simultaneously flying towards other bases and major cities and soon, everything I can see and feel will be vapourised and cease to exist. I had this daydream many times as a child, I have no idea how long it lasted but I can remember the clarity and metallic taste of it incredibly clearly. Did I want it to happen? Definitely not. Was I scared? No, although I remember an almost physical sense of shaking it off afterwards. Did I think it would happen? It’s hard to remember, maybe – but I wouldn’t have been alone in that if so. But anyway, the interesting point to me is that this wasn’t a dream that required sleep or the surrender of the conscious mind to the unconscious – I was presumably doing it “on purpose”, although what that purpose was I have no idea; nothing very nice anyway.

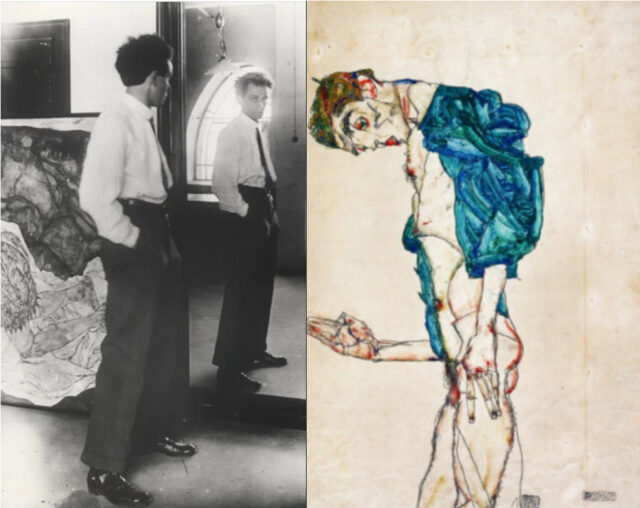

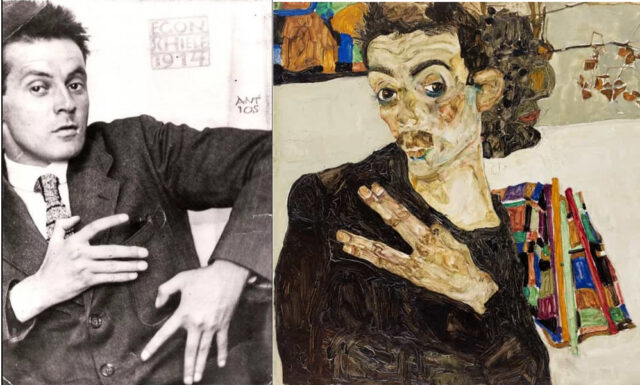

Probably most of us carry around a few daydreams with us, most I’m sure far more pleasant than that one. I can remember a few from my adolescence that were almost tangible then and still feel that way now (I would swear that I can remember what a particular person’s cheek felt like against my fingertips though I definitely didn’t ever touch it. As my childhood role model, Charlie Brown would say, “Augh!” Charles M. Schulz clearly knew about these things and still felt them vividly as an adult (as, more problematically, did Egon Schiele, subject of my previous article; but let’s not go into that). Most of the daydreams we keep with us into adulthood (or create in adulthood) are probably nicer baggage to carry around than the vapour trail one, unless you’re one of those people who fantasises about smashing people’s heads in with an iron bar (who has such a thing as an iron bar? Why iron? Wouldn’t brass do the job just as well and lead even better?) beyond the teenage years when violent daydreams are almost inevitable, but hopefully fleeting.

But thinking about your daydreams is odd, they are, like your thoughts and dreams, yours and nobody else’s, but where they come from in their detail seems almost as obscure as dream-dreams. Perhaps Freud would know. I have a couple of daydreams that have been lurking around for decades, but while I don’t believe in telekinesis or even the current obsession with affirmations and ‘manifesting,’ apparently I must be a bit superstitious; because if I wrote them down they might not come true innit?