I suppose I should warn people: this is pretty much all spoilers.

Television has always had one big advantage over cinema – time – which should really make it the better medium for drama. After all, the novel is almost always superior to the short story for depth, breadth, detail, plot and character development; and yet, there are more of all of those things in, say, the three hours of Scorsese’s Goodfellas than in 60+ years of Coronation Street. What happens in fact – even in shows that only last a few seasons – is more often stagnation, repetition, a growing sense of desperately trying to fight for ratings by increased sensationalism or controversy. But despite the smartass and I’m sure unoriginal title here (I intentionally haven’t checked), I don’t think television needs to be revolutionised, it just needs to act as though its virtues – especially the time and intimacy it has – are virtues, and not try to import the features of a Hollywood blockbuster into a more modestly sized format. But there is one thing that TV could and should learn from cinema; the satisfying (all different kinds of satisfying) ending that is mostly mandatory in film and in most cases isn’t just a tacked-on afterthought.

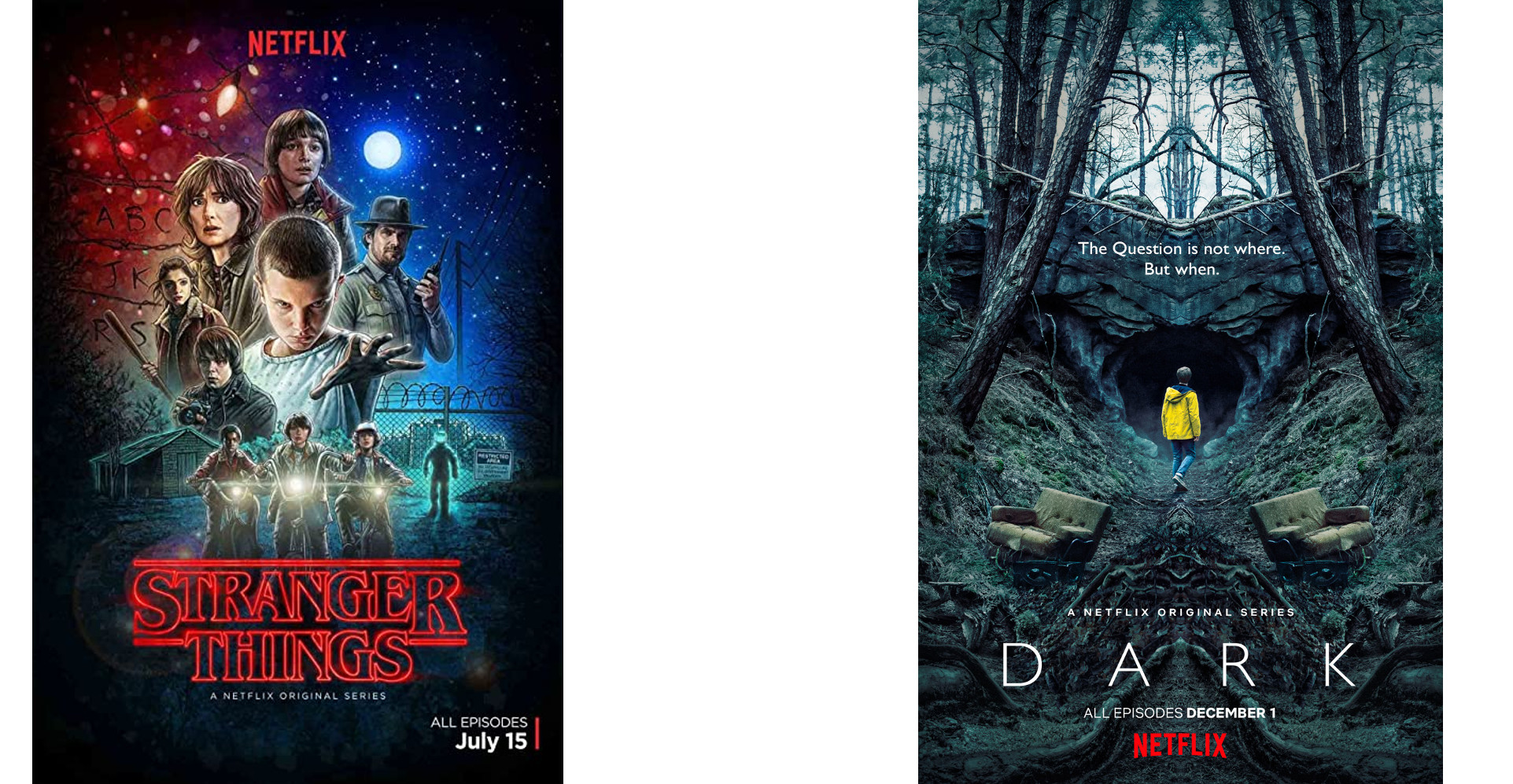

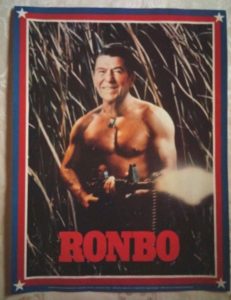

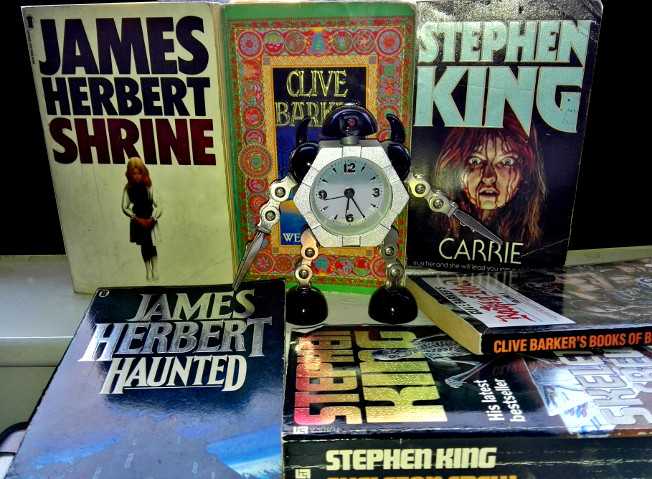

TV advertising as movie posters; Stranger Things embodying its 80s setting, Dark its disorienting fractured quality

I first saw mention of Dark online just after season one had launched, where it was described as a kind of German Stranger Things. The two shows are almost entirely unalike, but the comparison is a natural one; both belong to the world of the Netflix blockbuster, both are somewhere in the sci-fi/horror genre, both feature young protagonists, both are set (in the case of Dark, only partly) in the 80s. And both seem to owe something to successful movies, but the contrast here is a significant one; Stranger Things (especially in its opening, best season) owes a lot to JJ Abrams’s nostalgic, fun, Spielberg-esque Super 8 (2011), an end-of-the-70s-set movie that is in equal measures a sci-fi adventure movie and a rites of passage film about teenagers and friendship, ET-meets-Stand By Me. Super 8 is essentially a story about young teens trying to find their place in a world/universe that is bigger and scarier than they realised and discovering along the way that ‘the authorities’ aren’t to be trusted and that their parents are really just as in the dark about everything as the kids are themselves. And a space monster. It succeeds because it’s slick and well made and has a lot of heart, but also – especially – because the young cast were great; Stranger Things season one mirrored almost all of those things too.

But there is – thankfully, so far – no sequel to Super 8. In borrowing so heavily from highly cinematic sources, Stranger Things also borrowed the structure – including the big finale –of a Hollywood blockbuster. But like many of those, because it was successful it therefore demanded a sequel that was in no way implied by the original story. So what you had instead was a fairly enjoyable season two, with even more sense of “the 80s”, not the actual 80s experienced by people who were alive then, but endless, not always concurrent pop cultural references that in the end made it feel as weirdly dislocating as the 60s of a TV show like Heartbeat where Elvis Presley, the twist, hippies and the summer of love all seem to be happening at the same time. The story to season two though did have the authentic-in-a-way feel of an 80s horror movie sequel – a fun but slightly unsatisfactory Freddie’s Revenge, we-made-a lot-of-money-last-time, what-can-we-do-now type sequel. And then season three was the inevitable diminishing returns sequel, only now it didn’t even pretend to be the actual 80s at all, just the 80s that people who have seen cheesy Hollywood movies would experience, where Soviet Russians really were the almost robot-like villains of Rocky IV or Red Dawn. I feel like younger people might want to know that this was American paranoia/propaganda, rather than historical fact. Although I’m sure there really were Soviet spy stations (with people wearing actual military uniforms!) hidden under malls all over the US. This was a disappointingly stupid show and also – inevitably – suffered from the kind of awkwardness that always happens with casts of children as time passes, an issue from the Our Gang and Bowery Boys franchises of the 1930s onwards. Imagine what it might have been like if they’d made a Goonies sequel a couple of years later with teenage Goonies instead of children – the pre/early teens are very different, friendship-wise from what comes later, and although there’s a lot of bittersweet drama to be found in that, Stranger Things was barely concerned with it at all. But it was successful, so there will be more of it.

This is the downfall of blockbuster TV; whereas movie franchises limp to their inevitable demise, becoming weaker and weaker carbon copies of what went before, TV dramas (and sitcoms too, if they go on too long) devolve into soap operas, concerned more with the relationships between the protagonists instead of putting those characters into meaningful stories. And then, when the viewing figures fall, they get cancelled. Stranger Things 4 may be great – I hope it is – but it might also be a lot of squabbling teenagers in what should probably be the 90s by now but which may be marked – appropriately I guess – by references to Ghostbusters 2, Back To The Future 2 (or Friday the 13th Part 7 and A Nightmare on Elm Street 5), hair metal and whatever commercials, candy and hairstyles the producers think shout ‘late 80s’ most loudly. It would be nice though to have a bit of imagination and a proper ending. In TV terms I’d say it’s far better to have an end in sight and be missed when you go than to be cancelled and remembered as something that was once good but got milked to death; but that’s just me maybe.

Meanwhile Dark felt cinematic too, but in a very different way. Whereas Stranger Things seemed to have its genesis in Super 8, Dark seems to owe some of its ideas and a lot of its atmosphere to Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko (2001), a very different 80s-set film in which a troubled teenager is caught in a series of strange events caused by a loop in time which must be undone in order to restore equilibrium to his/the world; but at a tragic cost. The basic themes of Donnie Darko are not really a million miles removed from those of Super 8, but whereas that movie’s protagonists are in the awkward, bittersweet children-into-teens phase, discovering the boundaries of their childhood friendships and the awakening of sexual desire etc, Donnie is a depressed, disillusioned but still idealistic 17 year old, looking for answers to the big questions of life and death but finding that – like the Super 8 kids – no-one, however much authority they seem to have, really knows any more than he does. And it’s also about time travel.

What Dark did (I write this assuming they won’t spoil it with a 4th season) is what TV drama so rarely does, but which cinema almost always does – it has a sense of overall structure, an ending in mind even as it begins (more than that, that’s one of the major themes running through the show itself). Unlike with Stranger Things, seasons two and three of Dark were not only implied by the events of season one, they have to happen to bring the story to any kind of satisfactory close. One of the strengths of Stranger Things is that if it had been cancelled after the first season it would have been just as good; but Dark would have been incredibly frustrating. This is quite a fundamental difference; when the plot of a (drama) show becomes secondary to the characters it can absolutely still be great, it’s just that, while it remains popular enough to justify making it, it has no real need to be any good, like the aforementioned Friday the 13ths

On the other hand, a strength (and I guess from the financial point of view, a weakness) of Dark is that, as it stands now, the show can only be continued by ruining it and undoing the perfectly formed story that was told. That story (as implied from the beginning but explicitly mentioned from season two onwards) was an increasingly complicated knot (the moment where one character was revealed to be her own grandmother and therefore her own granddaughter was perhaps the pinnacle of the show’s brain-hurting complexity) and, in the end, Alexander the Great-like, the writers simply cut through it. But although that sounds disappointing – and initially, the final season felt like a sidestep rather than a continuation – it ultimately made total sense and explained every bizarre and apparently illogical detail of what had come before it, as well as reinforcing the significance of background details that were there from the very beginning of the show, such as the strange trefoil symbol that appeared on the doors to the time portals.

But although I’ve stressed the importance of the plot, where Dark really utilises the virtues of television over film is in the time it spends developing a whole set of characters, at various stages of their lives, in ways that make them feel real and believable. Some of the show’s initially least likeable secondary characters, such as the local Policeman Egon Tiedemann, in the end become tragic figures, not because of anything especially dramatic (though lots of dramatic things happen to them) but just because we see them, young, middle aged, old, repeating their mistakes, invariably making the wrong decisions and never really coming to grips with their own lives before they are over. It also makes us re-evaluate the villains as well as the heroes (sometimes there is no difference between the two). At the beginning of season one it’s immediately obvious that the apparent itinerant preacher Noah is a (slightly cheesy) villain. By the end of season three it turns out he wasn’t any kind of evil mastermind but was no better off than anyone else, a tragic, literally misconceived figure, trapped in circumstances beyond his control, doing horrible things in apparently good faith, to no avail whatsoever.

The representation of the same characters in different time periods is occasionally done in cinema – Richard Linklater and Martin Scorsese spring to mind – but it comes far more naturally to television, with its ability to really stretch out; and yet it hardly ever happens. Soap operas can run literally for decades, with actors ageing in real time and yet never lose the feeling of utter triviality that separates them from great drama; perhaps because although the characters inevitably end, the show trundles on; like life, arguably, but I’m not going to pursue that metaphor. It’s no coincidence that most soaps (in the UK at least) are named after their location, the one immutable element in the show.

The fact that – as in Donnie Darko – the ‘happy ending’ of Dark involves the death (or in this case the non-existence) of characters who the viewer has come to like, love, identify with, empathise with etc – and yet still feels like the right ending – is testament to the skill of the makers of the show. And more importantly – and here it goes beyond Donnie Darko – the final reveal of the origin of the temporal anomaly surrounding the town of Winden was right. Not some random occurrence like the aeroplane engine that ‘should’ have killed Donnie, but an event that logically implies all that follows and explains some of its more enigmatic characters (not least her-own-grandmother-and-granddaughter Charlotte). Written down, the basic theme sounds a bit trite – trying to change the past can destroy the present and future – but onscreen, with well drawn and (very) well acted characters, the idea (kind of like in Stephen King’s Pet Sematary) that in trying to bring back the dead you can awaken other things, is both powerful and emotionally engaging.

All of which is a very long way around to say that television doesn’t need to be revolutionised, it just needs to be seen for its own virtues and not as a kind of surrogate cinema. Hopefully the makers of Stranger Things get it right next time.

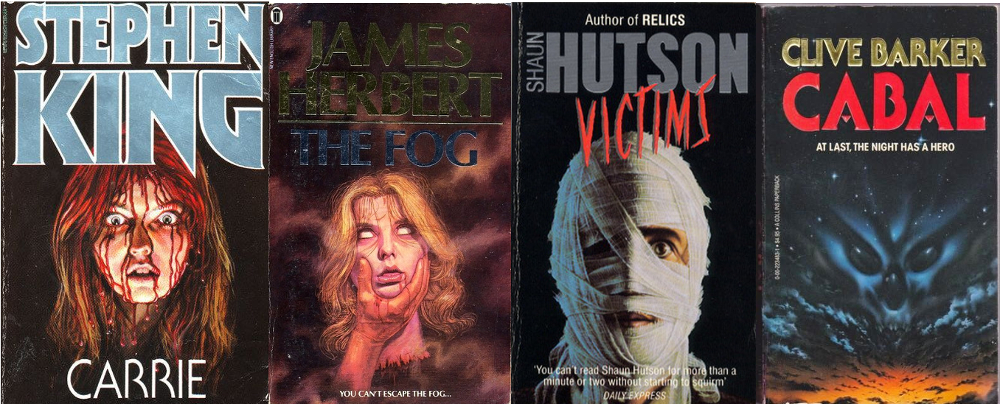

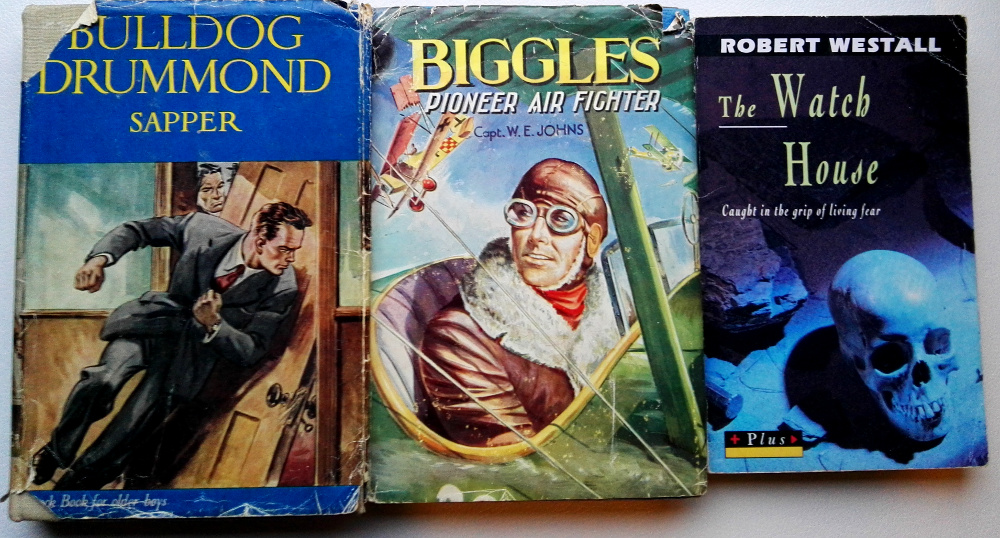

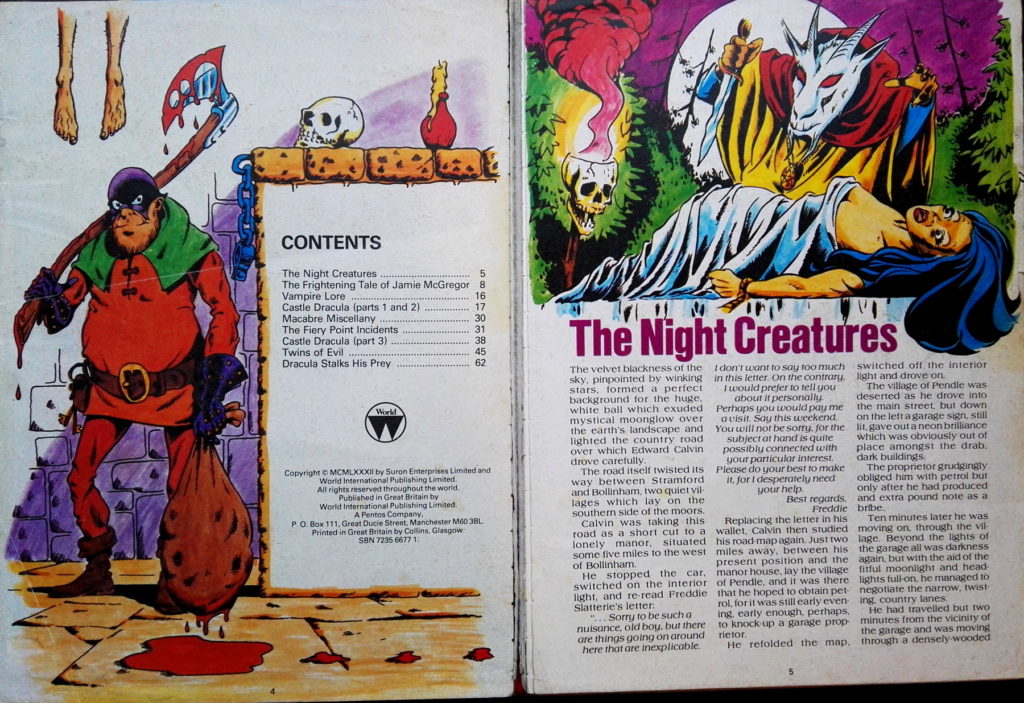

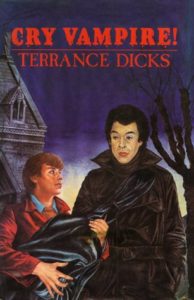

the Mobile Library (itself a very 80s detail although I’m sure they still exist) and loving them, and, later in Primary School Robert Westall’s The Scarecrows, The Watch House, The Wind Eye and The Devil on the Road made a big impression on me (and still stand up well when read as an adult). As a devotee of the phenomenally successful Fighting Fantasy gamebook series, I recall being particularly impressed by the horror-themed House Of Hell, which was very different from the swords & sorcery (or sci fi) leanings of the rest of the series.

the Mobile Library (itself a very 80s detail although I’m sure they still exist) and loving them, and, later in Primary School Robert Westall’s The Scarecrows, The Watch House, The Wind Eye and The Devil on the Road made a big impression on me (and still stand up well when read as an adult). As a devotee of the phenomenally successful Fighting Fantasy gamebook series, I recall being particularly impressed by the horror-themed House Of Hell, which was very different from the swords & sorcery (or sci fi) leanings of the rest of the series.