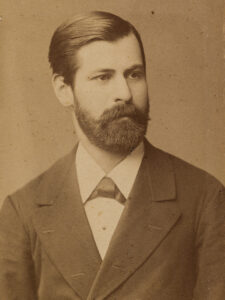

Whether you agree with Sigmund Freud that “the dream proves to be the first of a series of abnormal psychic formations” or that “one who cannot explain the origin of the dream pictures will strive in vain to understand [the] phobias, the obsessive and delusional ideas and likewise their therapeutic importance,” (The Interpretation of Dreams, 1913 translated by A.A. Brill) or not, dreams are a regular feature of human life regardless of culture, language, age etc, and so can’t be entirely without significance. I could go on about dreams at length like I did about honey in this previous post but I won’t – they are too pervasive in popular culture – just everywhere in both ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture; in books, and plays and art and films and songs (Dreams they complicate/complement my life, as Michael Stipe wrote). Dreams are everywhere, so that’s enough of that.

But what about daydreams? If dreams arrive uninvited from the unconscious or subconscious mind, then surely the things we think about, or dwell on, more-or-less deliberately are even more important? “Dwell on” is an interesting phrase – to dwell is “to live in a place or in a particular way” BUT the word ‘dwell’ also has a fascinating history that makes it seem like exactly the right word in this situation. From the Old English dwellan “to lead into error, deceive, mislead,” from Proto-Germanic dwaljana “to delay, hesitate” and related to dwelian “to be led into error, go wrong in belief or judgment” etc, etc, according to etymonline.com : I’ll put the whole of this in a footnote* because I think it’s fascinating. But the key point is that at some time in the medieval period its largely negative connotations disappeared and to “delay” become modified to mean “to stay.” But I like to think the old meaning of the word lingers in the subtext like dreams in the subconscious.

I could say something similar about my own use of the word “deliberately” above (“Things we dwell on … deliberately”) and even more so the phrase I nearly used instead, which was “on purpose” – but then this would become a ridiculously long and convoluted piece of writing, so that’s enough etymology for now.

The human mind is a powerful thing, even for those of us who don’t believe in telekinesis or remote viewing or ‘psychic powers’ in the explicitly paranormal sense. After all, your mind controls everything you think and nearly everything you do, to the point where separating the mind from the body, as western culture tends to do, becomes almost untenable. The euphemism “unresponsive wakefulness syndrome” has gained some traction in recent years because the dysphemism (had to look that word up, thought there must be an opposite) “persistent vegetative state” is something we fear and because of that fear, the loss of self, or as we perceive it, of humanity offends us. As fiction frequently demonstrates, despite the evidence it’s preferable for most of us to believe that even in that “vegetative” state, dreams of some kind must continue; because as human beings we are fully our mind in a way that we are only occasionally fully our body. One of the fears connected to the loss of self is that we lose the ability to choose what to think about, which is intriguing because that takes us again into the (might as well use the pompous word) realm of dreams.

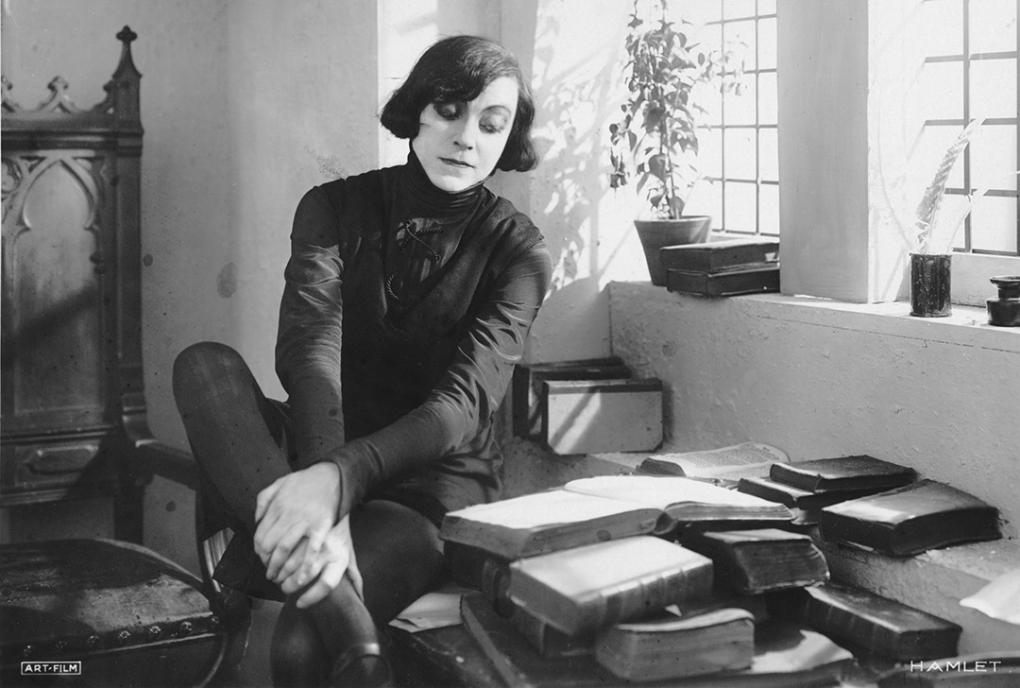

My favourite Shakespeare quote is the last line from this scene in Hamlet (Act 2 Scene 2)

Hamlet: Denmark’s a prison.

Rosencrantz: Then is the world one.

Hamlet: A goodly one, in which there are many confines, wards, and

dungeons, Denmark being one o’ th’ worst.

Rosencrantz: We think not so, my lord.

Hamlet: Why then ’tis none to you; for there is nothing either good or

bad, but thinking makes it so. To me it is a prison.

“There is nothing either good or bad, but thinking makes it so” seems to deny any possibility of objective morality, but its logic is undeniable. After all, you or I may think that [insert one of thousands of examples from current politics and world events] is ‘wrong’, but if [individual in position of power] doesn’t think so, and does the wrong thing, even if all of the worst possible outcomes stem from it, the most you can say is that you, and people who agree with you, think it was wrong. Hitler almost certainly believed as he went to the grave that he was a martyr who had failed in his grand plan only because of the betrayal and duplicity of others. I think that’s wrong, you hopefully think that’s wrong, even “history” (currently) thinks that’s wrong, but none of that matters to Hitler in his bunker in 1945, any more than Rosencrantz & Guildenstern finding Denmark to be a nice place if only their old friend Hamlet could regain his usual good humour makes any difference to Hamlet.

Anyway, onto daydreams or reveries (the latter is a nice word that feels a bit pretentious to say). The dictionary definitions of these words are mostly positive – a series of pleasant thoughts about something you would prefer to be doing or something you would like to achieve in the future. A state of abstracted musing. A loose or irregular train of thought occurring in musing or mediation; deep musing. There’s a school of thought that has been around for a long time but seems even more prevalent today, which values daydreams as not just ‘idle thoughts’, but as affirmations. Anyone who has tried to change their life through hypnosis or various kinds of therapy will find that daydreaming and visualising are supposed to be important aspects of your journey to a better you. In a way all of these self-help gurus, lifestyle coaches and therapists are saying the same thing; as Oscar Hammerstein put it, “You got to have a dream, If you don’t have a dream, How you gonna have a dream come true?” But is making your dreams, even your daydreams, come true necessarily a good thing?

I seem to remember once reading that if you can focus all of your attention on something for 15 seconds you’ll remember it forever. Whether or not that’s true, every time I see a vapour trail in an otherwise blue sky, I have the same combination of thought and image* which must date from the age of 9 or 10 or so. I realise that people telling you their dreams is boring (or so people say, I never find it to be so), but you don’t have to keep reading.

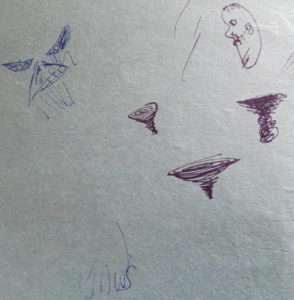

I can see the fluffy, white trail against the hot, pale blue sky (it’s summer, the sun is incandescent and there are no clouds) and as my eye follows it from its fraying, fading tail to its source, I can see the nose cone of the ‘plane’ glinting in the sun, black or red and metallic. It looks slow, leisurely even, but the object is travelling at hundreds of miles an hour. I know there’s no pilot inside that warm, clean shell (I can imagine feeling its heat, like putting your hand on the bonnet or roof of a car parked in direct sunshine; only there are rivets studding the surface of this machine). I’m shading my eyes with my hand, watching its somehow benign-looking progress, but I know that it’s on its way to the nearby airforce base and that other missiles are simultaneously flying towards other bases and major cities and soon, everything I can see and feel will be vapourised and cease to exist.

I had this daydream many times as a child, I have no idea how long it lasted but I can remember the clarity of it and its metallic taste incredibly clearly. Did I want it to happen? Definitely not. Was I scared? No, although I remember an almost physical sense of shaking it off afterwards. Did I think it would happen? It’s hard to remember; maybe – but I wouldn’t have been alone in that if so. But anyway, the interesting point to me is that this wasn’t a dream that required sleep or the surrender of the conscious mind to the unconscious – I was presumably doing it “on purpose”, although what that purpose was I have no idea; nothing very nice anyway.

Probably most of us carry around a few daydreams with us, most I’m sure far more pleasant than that one. I can remember a few from my adolescence that were almost tangible then and still feel that way now (I would swear that I can remember what a particular person’s cheek felt like against my fingertips though I definitely didn’t ever touch it. As my childhood role model, Charlie Brown would say, “Augh!” Charles M. Schulz clearly knew about these things and still felt them vividly as an adult (as, more problematically, did Egon Schiele, subject of my previous article; but let’s not go into that).

Most of the daydreams we keep with us into adulthood (or create in adulthood) are probably nicer baggage to carry around than the vapour trail one, unless you’re one of those people who fantasises about smashing people’s heads in with an iron bar. Iron feels right, but why? Who has such a thing as an iron bar? Wouldn’t brass do the job just as well and lead even better? Violent daydreams are almost inevitable during the teenage/school years, but they are hopefully fleeting.

But thinking about your daydreams is odd. They are, like your thoughts and dreams, yours and nobody else’s, but where they come from in their detail seems almost as obscure as night-dreams. Perhaps Freud would know. I have a couple of daydreams that have been lurking around for decades, but while I don’t believe in telekinesis or even the current obsession with affirmations and ‘manifesting,’ apparently I must be a bit superstitious; because if I wrote them down they might not come true innit?

* there is another thought: “first you look so strong/then you fade away” but it’s a line from a song and came later and failed to replace the earlier thought

I am not at all averse to folk music of various types, but I have to admit that on the whole I avoid the folk music of my own country. Partly it’s because most of the Scottish folk music I have come in contact with is dance music. I’m with Mark E. Smith on that one; I don’t want to dance (he may of course have contradicted that somewhere in the hundreds of albums he’s made since 1979). There are lots of kinds of dance music I do like, but the memory of Scottish country dancing at high school; of accordions, fiddles, ceilidhs etc; it’s just not for me. However, on their debut album, Inver, HAV make music that seamlessly combines the instrumentation and feel (and some of the tunes) of Scottish folk music with delicately atmospheric ambient electronica and field recordings and it is quite simply beautiful. Alternately bracing and embracing, it really seems to capture the feeling of the landscapes I grew up in, while also making the past (traditional songs like Loch Tay Boat Song, Peggy Gordon etc) feel present and the present timeless; which is surely what folk music is all about.

I am not at all averse to folk music of various types, but I have to admit that on the whole I avoid the folk music of my own country. Partly it’s because most of the Scottish folk music I have come in contact with is dance music. I’m with Mark E. Smith on that one; I don’t want to dance (he may of course have contradicted that somewhere in the hundreds of albums he’s made since 1979). There are lots of kinds of dance music I do like, but the memory of Scottish country dancing at high school; of accordions, fiddles, ceilidhs etc; it’s just not for me. However, on their debut album, Inver, HAV make music that seamlessly combines the instrumentation and feel (and some of the tunes) of Scottish folk music with delicately atmospheric ambient electronica and field recordings and it is quite simply beautiful. Alternately bracing and embracing, it really seems to capture the feeling of the landscapes I grew up in, while also making the past (traditional songs like Loch Tay Boat Song, Peggy Gordon etc) feel present and the present timeless; which is surely what folk music is all about.

Despite the title, after the squeaks and pings intro of Puddle Ripple (the first of several strangely tense Lash compositions), Extremophile as a whole isn’t especially extreme (unless you hate jazz in general I guess). It is certainly an imaginative and wide-ranging album, featuring both a peculiar and beautifully atmospheric jazz exploration of the

Despite the title, after the squeaks and pings intro of Puddle Ripple (the first of several strangely tense Lash compositions), Extremophile as a whole isn’t especially extreme (unless you hate jazz in general I guess). It is certainly an imaginative and wide-ranging album, featuring both a peculiar and beautifully atmospheric jazz exploration of the