“His manner was so friendly that I forgot to put on my cockney accent, and he looked closely at me, and said how painful it must be for a man of my stamp, etc. Then he said, ‘I say, you won’t be offended, will you? Do you mind taking this?’ ‘This’ was a shilling, with which we bought some tobacco and had our first smoke that day. This was the only time in the whole journey when we managed to tap money.”

George Orwell, ‘Hop-Picking’, October 1931. Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell Volume 1 An Age Like This 1920-1940. Penguin, 1968, p. 83

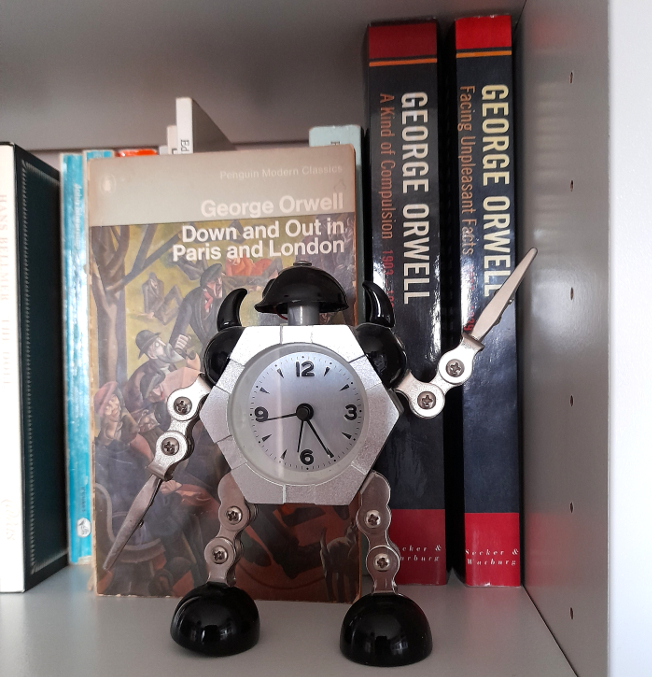

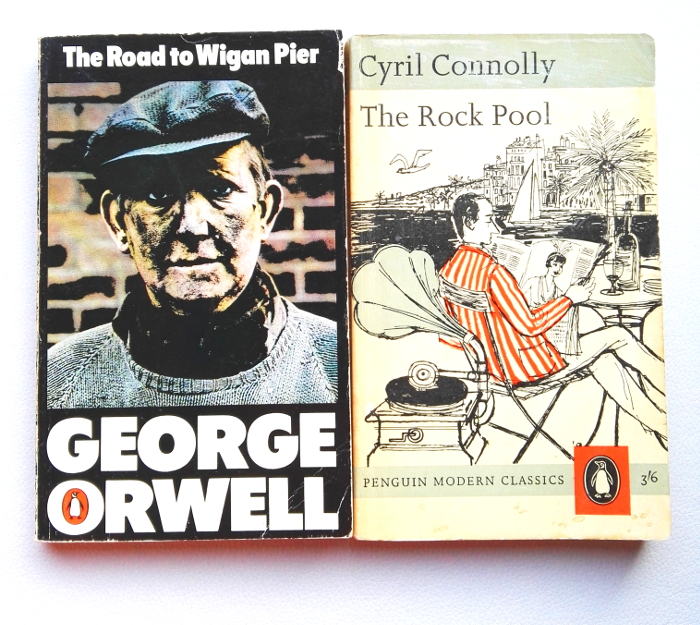

Clearly, the old school tie works, even when it isn’t worn. Incidents like this pop up several times in George Orwell’s writings of the 30s, in articles like “The Spike” and in Down and Out in Paris and London (1933) etc., and they always make him uncomfortable. The reminder of the deference that he was, in his original identity as old Etonian Eric Blair, accustomed to and had been trained for in his daily life was both welcome and unwelcome. Unwelcome, because firstly, it was embarrassing to be ‘unmasked’ in front of people with whom he had become friends precisely because at the level of society at which they existed – and in these writings it is the poorest of the working class or the unemployed and destitute – there were no class distinctions anymore; as he says in Down and Out in Paris and London, regarding a typical London lodging house:

All races, even black and white, mixed in it on terms of equality. There were Indians there, and when I spoke to one of them in bad Urdu he addressed me as ‘tum’ – a thing to make one shudder, if t had been India. We had got below the range of colour prejudice.

George Orwell, Down and Out in Paris and London, Gollancz 1933, p. 150

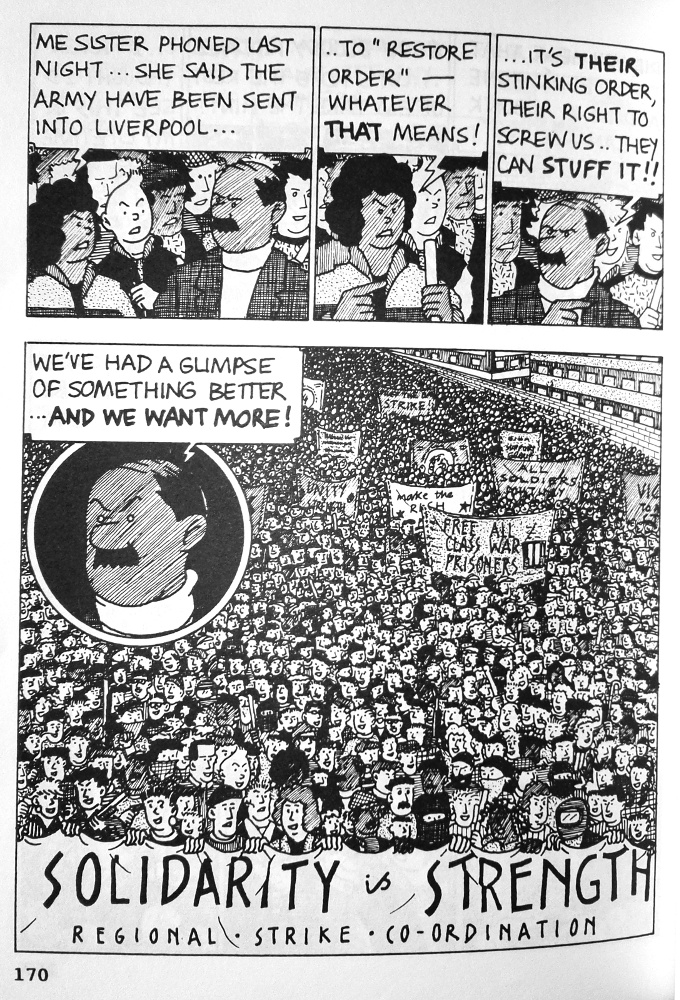

Though Orwell was sometimes taken aback by the levelling effect that poverty had, he welcomes it too – his occasional unmasking as a “gentleman” was an unpleasant reminder of his abandoned life as a police officer and tool of colonial oppression in Burma. But it was also useful in a way – not just because money and gentle treatment was welcome after weeks or months of hardship, but because it was a stark and simple illustration of exactly the kind of injustice, inequality and disparity he sought to draw attention to with his writing. Orwell is happy to write openly about his deception, partly because it was essentially harmless and necessary, in order to truly experience the kind of life he wanted to write about. But perhaps he was also comfortable doing so because, much as he would have liked to have ‘proletarian’ readers, – and probably did have a few – he was mainly writing for an audience of his peers; the political class who could, if they really wanted to, improve the lives of the vast, faceless mass of unemployed and homeless that they were no doubt aware of, but preferred to think about, if at all, as feckless layabouts who probably deserved their lowly status.

There were of course many working-class readers in the 1930s, possibly even more than there are now, given the enormous output of publishers of what Orwell calls “cheap novels” in that era, not to mention the libraries, newspapers and periodicals designed to cater for every possible niche hobby, that he lists in his 1940 essay ‘Boys’ Weeklies‘. In fact, he notes in Down and Out in Paris and London, that even the unemployed, homeless underclass of itinerant tramps were voracious readers of Buffalo Bill novels and the like, whenever they could get hold of them. Of course, even the most ‘proletarian’ newspapers and publishing houses were owned in the 1930s by people with backgrounds similar to Orwell’s – and by and large they still are. Likewise, at that point it would probably have seemed natural that it was this same class who were to be found running the more recently established broadcasters, notably the BBC. Natural, because before WW2, the role of the upper class was still very much seen as ‘the management’ of the British Empire with the middle class as administrators, but both far outnumbered by the working class who did the work (well, management and administration are work too, but you know what I mean).

What might – or on reflection, might not – have surprised Orwell is that 70+ years after his death, when class differences have been (or appear to have been) diminished, the leaders, for a while, of the relatively extreme left and right-wings of British politics and who appealed openly to the working classes should have been ex-public schoolboys called Nigel and Jeremy. It might surprise him too, to find that members of the openly-elitist public-school educated minority to which he belonged would still be going around pretending to be ‘ordinary blokes,’* almost like he did, in newspapers and especially on television. There are differences in the 21st century; the working class, although now interchangeable to a far greater extent with the middle class, are by virtue of numbers, the main demographic catered to by TV and so whereas Orwell was trying to blend with his social inferiors to prove a point to his peers, undercover toffs today are mostly trying to blend with them in order to appeal directly to, and ultimately financially benefit from, those working class people.

* even as a working class person I inwardly cringe writing “ordinary bloke,” but I think it’s the correct phrase in this instance for what these people think they represent. But bloody hell, “ordinary bloke” – from here on in I’ll just write “OB”

Some observations; the incognito upper class type seems mostly to be a male thing. The female counterparts of these kinds of commentators and presenters are there – Kirstie Allsop or Mary Berry spring to mind, but unlike the men they seem content to be unselfconsciously posh, which is fair enough.

There are various different versions of the type. Some are benign and essentially innocent; people who, one assumes, would have been dropouts whether or not opportunities in TV beckoned and whose scruffy clothes and sloppy speech were probably originally adopted to annoy their parents or just as a way of opting out of the expectations that come along with class privilege (but you get to keep the privilege anyway, so… )

Since at least the 1960s, the pop and rock music business has always been full of these kind of people – and since the 60s too, their opposite has existed; the vastly wealthy who weren’t born into an upper class background. It’s possible that these people, rock stars and entrepreneurs act in some ways as role models to the posh OBs

.

The kind of TV shows made by the benign-dropout demographic tend to reflect a somewhat genteel outsider status* and are often geared towards niche hobbies and interests, so that the whole thing has the aura of the upper class dilletante of the 20s, dabbling in publishing modernist poetry or abstract art. This is a public role in a way, but although it allows the presenter to share his views on the world and life in general, it feels essentially more like a sharing of enthusiasms than anything overtly or covertly patronising or manipulative.

*I do realise that every word of this is probably wildly unfair and doesn’t take into account any of the genuine struggles that come with class expectations etc: oh well.

Where it feels less benign and perhaps more deceptive is when the “OB”-ness of the presenter is an embodiment of what he thinks an actual “ordinary bloke” is like. Perhaps not surprisingly, the evidence suggests that the posh public schoolboy assumes that the OB is what the tabloid press – also, it should be noted, owned by posh ex-public schoolboys – tries to condition them to be. No doubt there are working class people who are old fashioned, conservative, unreconstructedly misogynistic, knee-jerk racist xenophobes, impatient with anything that might seem effete – but it’s also clear that the tabloid press wants them to be that way and does what it can to continue and spread these attitudes. Which is logical enough; the whole point of the class system is to preserve itself and ensure the survival of privilege, blood lines and all that crap. An interesting question – which I don’t know the answer to – is whether it is it self-awareness or self-deception that makes the ersatz OB hide his upper-class accent for TV purposes. Either way it’s probably a wise move, because if there’s one thing that seems risibly effete to the kind of proletarian the tabloid press imagines, it’s the particular kind of upper class speech nurtured in the most expensive and exclusive public schools.

It seems that on the whole, the public is pretty much okay with the fake OB as entertainer and cultural commentator; except for those regular instances when he goes “too far.” But the whole raison d’etre of this kind of public figure is to test the boundaries of what is acceptable, always with the safety net that the whole persona is so obviously contrived that nothing they say can ever be taken seriously, surely? But it’s notable that the self-consciously “outrageous” incidents that pop up from time to time, that seem to simultaneously mark out where those boundaries are and make reactionary attitudes just a little bit more acceptable, always come from the same place. It’s that sweet spot where the tabloid-owner’s classist projection of the “ordinary bloke” – impatient with having to respect people, constantly at war with ‘political-correctness-gone-mad’ – happens to coincide and blend with the underlying upper class snobbery and prejudice that we aren’t supposed to notice, because of that bluff OB exterior. Class prerogatives, racism, classism, the fear of privilege being eroded, the snooty, outraged ‘don’t-you-know-who-I-am?’ loathing of having to deal with or, god forbid, defer to social or racial inferiors; the fear of change. But never mind, it’s all just a joke, innit, and if you take it seriously then you are a puritanical killjoy and who would ever want to be that? No self-respecting ordinary bloke, anyway.