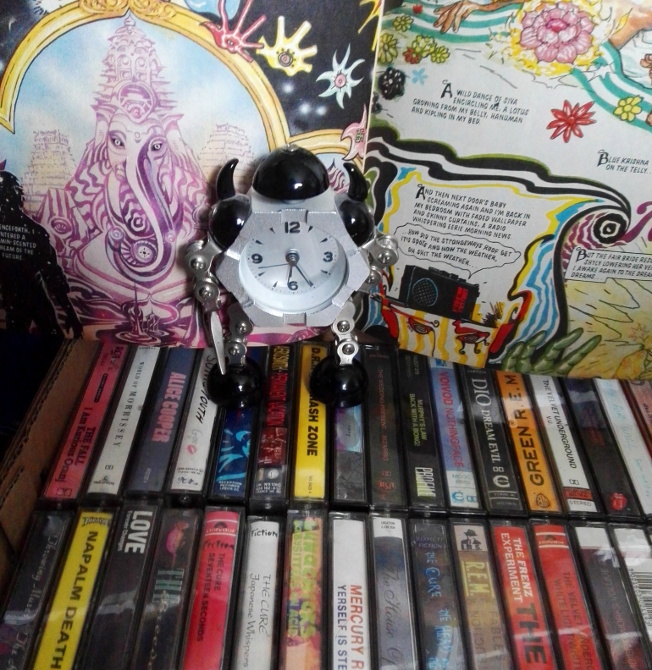

Between the ages of 14 and 16 or thereabouts, the things I probably loved the most – or at least the most consistently – were horror (books and movies) and heavy metal.

These loves changed (and ended, for a long time) at around the same time as each other in a way that I’m sure is typical of adolescence, but which also seemed to reflect bigger changes in the world. Reading this excellent article that references the end of the 80s horror boom made me think; are these apparent beginnings and endings really mainly internal ones that we only perceive as seismic shifts because of how they relate to us? After all, Stephen King, Clive Barker, James Herbert & co continued to have extremely successful careers after I stopped buying their books, and it’s not like horror movies or heavy metal ground to a halt either. But still; looking back, the turn of the 80s to the 90s still feels like a change of era and of culture in a way that not every decade does (unless you’re a teenager when it happens perhaps?) But why should 1989/90 be more different than say, 85/86? Although time is ‘organised’ in what feels like an arbitrary manner (the time it takes the earth to travel around the sun is something which I don’t think many of us experience instinctively or empirically as we do with night and day), decades do seem to develop their own identifiable ‘personalities’ somehow, or perhaps we simply sort/filter our memories of the period until they do so.

“The 80s” is a thing that means many different things to different people; but in the western world its iconography and soundtrack have been agreed on and packaged in a way that, if it doesn’t necessarily reflect your own experience, it at least feels familiar if you were there. What the 2010s will look like to posterity is hard to say; but the 2020s seem to have established themselves as something different almost from the start; whether they will end up as homogeneous to future generations as the 1920s seem to us now is impossible to say at this point; based on 2020 so far, hopefully not.

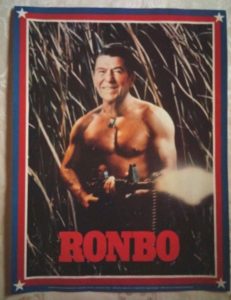

I sometimes feel like my adolescence began at around the age of 11 and ended some time around 25, but still, my taste in music, books, films etc went through a major change in the second half of my teens which was surely not coincidental. But even trying to look at it objectively, it really does seem like everything else was changing too. From the point of view of a teenager, the 80s came to a close in a way that few decades since have done; in world terms, the cold war – something that had always been in the background for my generation – came to an end. Though that was undoubtedly a euphoric moment, 80s pop culture – which had helped to define what ‘the west’ meant during the latter period of that war – seemed simultaneously to be running out of steam.

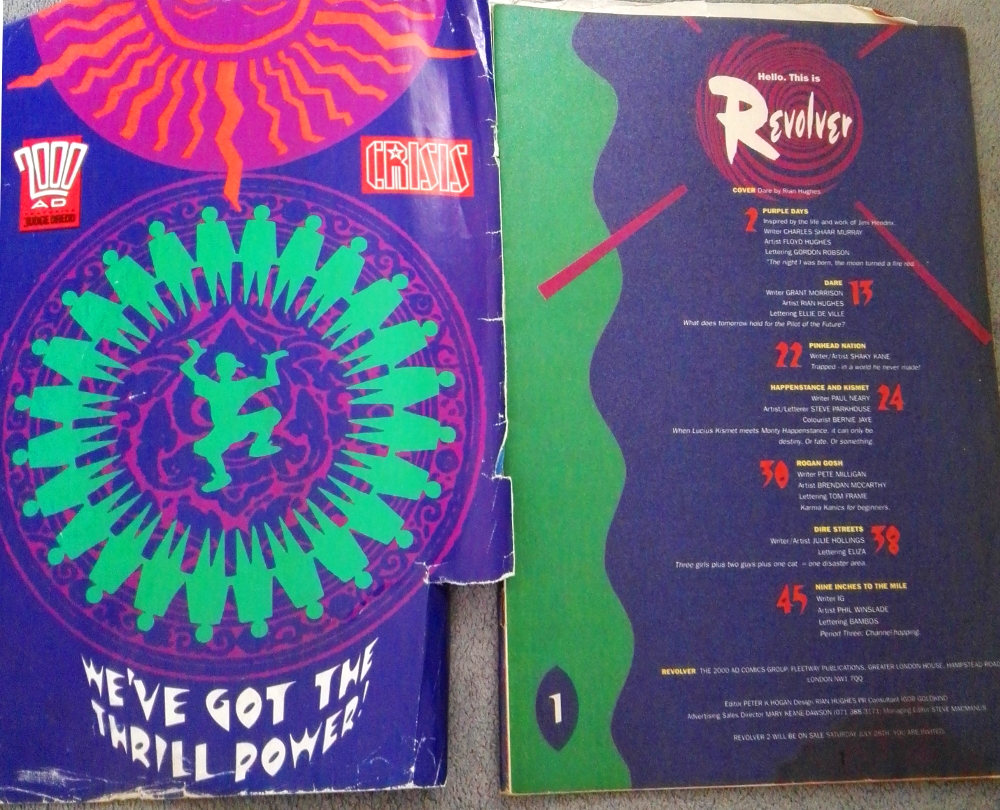

My generation grew up with a background of brainless action movies starring people like Arnold Schwarzenegger and Sylvester Stallone, who suddenly seemed to be laughable and obsolete, teen comedies starring ‘teens’ like Andrew McCarthy and Robert Downey, Jr who were now uneasily in their 20s. We had both old fashioned ‘family entertainment’ like Little & Large and Cannon & Ball which was, on TV at least. in its dying throes; but then so was the ‘alternative comedy’ boom initiated by The Young Ones, as its stars became the new mainstream. The era-defining franchises we had grown up with – Star Wars, Indiana Jones, Ghostbusters, Back to the Future, Police Academy – seemed to be either finished or on their last legs. Comics, were (it seemed) suddenly¹ semi-respectable and re-branded as graphic novels, even if many of the comics themselves remained the same old pulpy nonsense in new, often painted covers. The international success of Katsuhiro Otomo’s Akira in 1988 opened the gates for the manga and anime that would become part of international pop culture from the 90s onwards.

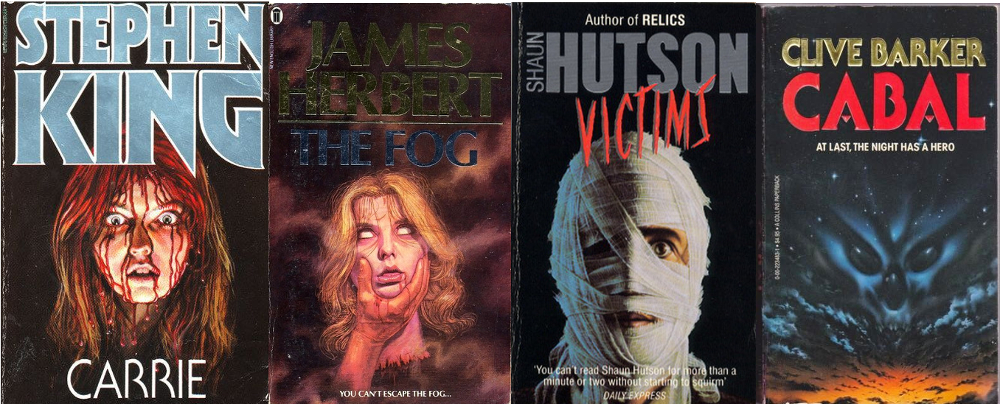

Those aforementioned things I loved the most in the late 80s, aged 14-15 – horror fiction and heavy metal music – were changing too. The age of the blockbuster horror novel wasn’t quite over, but its key figures; Stephen King, James Herbert, Clive Barker², Shaun Hutson – all seemed to be losing interest in the straightforward horror-as-horror novel³, diversifying into more fantastical or subtle, atmospheric or ironic kinds of stories. In movies too, the classic 80s Nightmare on Elm Street and Friday the 13th franchises – as definitively 80s as anything else the decade produced – began to flag in terms of both creativity and popularity. Somewhere between these two models of evolution and stagnation were the metal bands I liked best. These seemed to either be going through a particularly dull patch, with personnel issues (Iron Maiden, Anthrax) or morphing into something softer (Metallica) or funkier Suicidal Tendencies). As with the influence of Clive Barker in horror, so bands who were only partly connected with metal (Faith No More, Red Hot Chilli Peppers) began to shape the genre. All of which occurred as I began to be obsessed with music that had nothing to do with metal at all, whether contemporary (Pixies, Ride, Lush, the Stone Roses, Happy Mondays, Jesus Jones – jesus, the Shamen etc) or older (The Smiths, Jesus and Mary Chain, The Doors⁴, the Velvet Underground).

Still; not many people are into the same things at 18 as they were at 14; and it’s tempting to think that my feelings about the end of the decade had more to do with my age than the times themselves; but they were indeed a-changing, and a certain aspect of the new decade is reflected in editor Peter K. Hogan’s ‘Outro’ to the debut issue of the somewhat psychedelically-inclined comic Revolver (published July 1990):

Why Revolver?

Because what goes around comes around, and looking out my window it appears to be 1966 again (which means – with any luck – we should be in for a couple of good years ahead of us). Because maybe – just maybe – comics might now occupy the slot that rock music used to. Because everything is cyclical and nothing lasts forever (goodbye, Maggie). Because the 90s are the 60s upside down (and let’s do it right, this time). Because love is all and love is everything and this is not dying. Any more stupid questions?

This euphoric vision of the 90s was understandable (when Margaret Thatcher finally resigned in 1990 there was a generation of by now young adults who couldn’t remember any other Prime Minister) but it aged quickly. The ambiguity of the statement ‘the 90s are the 60s upside down’ is embodied in that disclaimer (and let’s do it right, this time) and turned out to be prophetic; within a month of the publication of Revolver issue1 the Gulf War had begun. Aspects of that lost version of the 90s lived on in rave culture, just as aspects of the summer of love lived on through the 70s in the work of Hawkwind and Gong, but to posterity the 90s definitely did not end up being the 60s vol.2. In the end, like the 80s, the 90s (like every decade?) is defined, depending on your age and point of view, on a series of apparently incompatible things; rave and grunge, Jurassic Park and Trainspotting, Riot Grrrl and the Spice Girls, New Labour and Saddam Hussein.

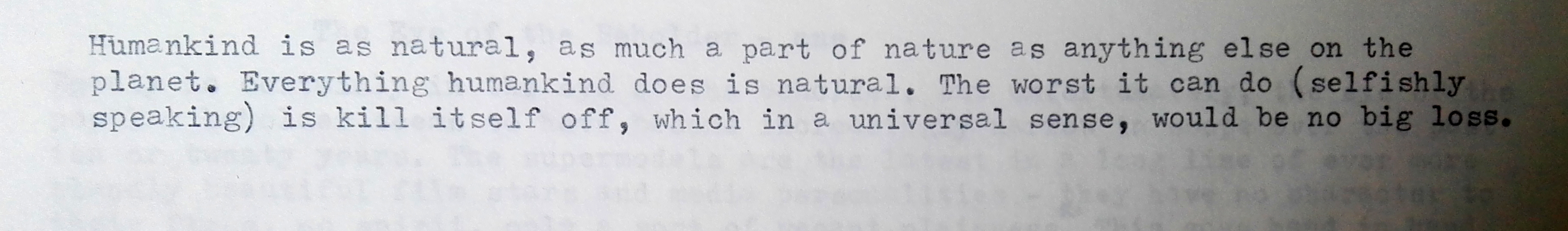

That tiny oasis of positivity in 1990 – between the Poll Tax Riots on 31st March and the declaration of the first Gulf War on the 2nd August is, looking back, even shorter than I remember, and some of the things I loved in that strange interregnum between adolescence and adulthood (which lasted much longer than those few months) – perhaps because they seemed grown up then – are in some ways more remote now than childhood itself. So… conclusions? I don’t know, the times change as we change and they change us as we change them; a bit too Revolver, a lot too neat. And just as we are something other than the sum of our parents, there’s some part of us too that seems to be independent of the times we happen to exist in. I’ll leave the last words to me, aged 18, not entirely basking in the spirit of peace and love that seemed to be ushered in by the new decade.

¹ in reality this was the result of a decade of quiet progress led by writers like Alan Moore, Neil Gaiman and Frank Miller

² although 100% part of the 80s horror boom, Barker is perhaps more responsible than any other writer for the end of its pure horror phase

³ Stephen King’s Dark Tower series, though dating from earlier in the 80s, appeared in print with much fanfare in the UK in the late 80s and, along with the more sci-fi inflected The Tommyknockers and the somewhat postmodern The Dark Half seemed to signal a move away from the big, cinematic horror novels like Pet Sematary, Christine, Cujo et al. In fact, looking at his bibliography, there really doesn’t appear to be the big shift around the turn of the 90s that I remember, except that a couple of his new books around that time (Dark Tower III, Needful Things, Gerald’s Game for one reason or another didn’t have half the impact that It had on me. That’s probably the age thing). James Herbert, more clearly, abandoned the explicit gore of his earlier work for the more or less traditional ghost story Haunted (1988) and the semi-comic horror/thriller Creed (1990)– a misleadingly portentous title which always makes me think of that Peanuts cartoon where Snoopy types This is a story about Greed. Joe Greed lived in a small town in Colorado… Clive Barker, who had already diverged into dark fantasy with Weaveworld, veered further away from straightforward horror with The Great & Secret Show while reliably fun goremeister Shaun Hutson published the genuinely dark Nemesis, a book with little of the black humour – and only a fraction of the bodycount – of his earlier work. ⁴ the release of Oliver Stone’s The Doors in 1991 is as 90s as the 50s of La Bamba (1987) and Great Balls of Fire (1989) was 80s. Quite a statement.