There have been a lot of obituaries for the great Mark E. Smith in the last week. This will not be one of the better ones, but it is my one. In my experience, the bands you love in your teens are, although they have a special place in your memory, mostly not the same bands you listen to for the rest of your life (to date). But unlike most of my favourite artists from those long years between 16 and 20 or thereabouts, I never went off The Fall, I just didn’t listen to them very often. But whenever I did, they seemed just as strange and clever and funny and unique as they had the first time I heard them.

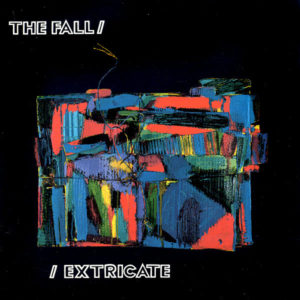

The Fall are legendarily supposed to be a hard band to like, or to get into, but I never found it to be so. The hard-to-like quality obviously has something to do with their spiky, unpredictable sound (and Mark E. Smith’s indomitable/hectoring voice) but is perhaps also due to the fact that – for the most part – their music doesn’t appeal to the emotions, it is not (hopefully) about you; nobody (as far as I know) wallows in The Fall, the way as an adolescent I wallowed in The Cure or The Smiths or the Cranes or whoever it might be. The first Fall song I heard was a snippet of then-current single ‘Telephone Thing‘ (a funky, catchy wah-wah-led pop song with a phone-tapping theme, which namechecks EastEnders actress Gretchen Franklin – i.e. as typically atypical as any Fall single) on The Chart Show, which was enough to make me buy its parent album, Extricate. As a reader of the music weeklies (Melody Maker was my favourite, but I often bought NME and Sounds as well) I was of course aware of The Fall, and specifically Mark E. Smith, at that point – as he was to remain – a figure who polarised the magazines’ writers, while – unlike say Morrissey or Robert Smith – having the (admittedly sometimes grudging) respect, seemingly, of all of them.

Extricate is in itself a classic Fall album, but it was intriguing in all kinds of ways. I liked. firstly, the tunes, but also the the mix of the un-selfconscious artiness of the abstract cover painting/assemblage by contemporary artist Anthony Frost, with the barbed humour of the lyrics (the album contains the classic ‘British People In Hot Weather‘as well as the aforementioned ‘Telephone Thing‘ and (I have the cassette version) ‘Arms Control Poseur‘). But one of the great things about coming to this – or I think any – Fall album as an introduction to the band, is that it hints at so much more than it contains. This, the reviews said, was an unusually accessible/conventional Fall album and indeed, Mark E. Smith’s sleevenote reinforced that impression:

There is no central track, as I’ve/we’ve tried to give out The Fall as it should be and not as it is perceived. Therefore, the first half of the disc reflects on things witnessed and/or sensed, while the second half is NOW. This means there’s a thin dish-up of stories and characters etc, but that format’s well flogged and pushed of recent, so hopefully EXTRICATE’s simplicity will confound all bores, imitators and anxiety mongers./ EXTRICATE! All the best from M.E.S.

This was odd. Mark E. Smith reminded me of nothing so much as Alex from A Clockwork Orange;  sophisticated, articulate, menacing but not unfriendly. A few years later, when I began to read Wyndham Lewis I was reminded irresistibly of Mark E. Smith. And indeed the whole of The Fall’s early work is extremely Vorticist/BLAST-like. I didn’t know though until quite recently that Mark E. Smith was a fellow Wyndham Lewis fan (though I think MES often agreed with Lewis where I don’t) – it seems so obvious now. And the reference to stories and characters was intriguing; if this was The Fall gone normal then what did they sound like before?? I think the next album I bought might have been the essential compilation of early material Palace Of Swords Reversed; here were ‘Marquis Cha-Cha‘, a story about a Lord Haw Haw character stranded in South America which opens

sophisticated, articulate, menacing but not unfriendly. A few years later, when I began to read Wyndham Lewis I was reminded irresistibly of Mark E. Smith. And indeed the whole of The Fall’s early work is extremely Vorticist/BLAST-like. I didn’t know though until quite recently that Mark E. Smith was a fellow Wyndham Lewis fan (though I think MES often agreed with Lewis where I don’t) – it seems so obvious now. And the reference to stories and characters was intriguing; if this was The Fall gone normal then what did they sound like before?? I think the next album I bought might have been the essential compilation of early material Palace Of Swords Reversed; here were ‘Marquis Cha-Cha‘, a story about a Lord Haw Haw character stranded in South America which opens

“He can never go home

Stranded in South America, nothing to go home for

Just another Brit in the bar

Hernandez Fiendish comes over to me

Offers a job as broadcaster…”

who else was writing songs like that? Or ‘Leave The Capitol‘ (“exit this Roman shell!“) or, even more peculiarly, ‘Wings‘:

“Day by day

The moon gains on me

Purchased pair of flabby wings

I took to doing some hovering”

And that’s just the lyrics; another thing about The Fall that made an impression on me early on was that, although MES was incredibly fussy and perfectionist about the band’s music, he wasn’t snobbish in the usual way; no tune, if it was catchy, was too silly for Mark E. Smith. Think of the speedy but somehow miniature-sounding rock guitar on ‘Underground Medicine‘ or loping, bouncy beat to ‘Gramme Friday‘ or the oddly jaunty, countryish ‘Fit And Working Again‘. or the kazoo on ‘The North Will Rise Again‘– this was ‘angular’ (the definitive descriptive term for late 70s/early 80s UK indie rock) if you like, but it was not standard ‘post-punk’ music, nor was it (as it could easily have been) twee in that beloved ramshackle UK indie/C86 kind of way. Perhaps because Mark E. Smith was not (99% of the time) a melodic singer, the band could play anything behind him and it sounded right. When, at the beginning of one of my favourite songs, ‘Slates‘, MES shouts ‘this is the definitive rant‘ he’s nailing part of the charm of his work. As long as the rant was in place, no tune was too small, too jingly or too silly to make something worthwhile out of.

And that’s just the lyrics; another thing about The Fall that made an impression on me early on was that, although MES was incredibly fussy and perfectionist about the band’s music, he wasn’t snobbish in the usual way; no tune, if it was catchy, was too silly for Mark E. Smith. Think of the speedy but somehow miniature-sounding rock guitar on ‘Underground Medicine‘ or loping, bouncy beat to ‘Gramme Friday‘ or the oddly jaunty, countryish ‘Fit And Working Again‘. or the kazoo on ‘The North Will Rise Again‘– this was ‘angular’ (the definitive descriptive term for late 70s/early 80s UK indie rock) if you like, but it was not standard ‘post-punk’ music, nor was it (as it could easily have been) twee in that beloved ramshackle UK indie/C86 kind of way. Perhaps because Mark E. Smith was not (99% of the time) a melodic singer, the band could play anything behind him and it sounded right. When, at the beginning of one of my favourite songs, ‘Slates‘, MES shouts ‘this is the definitive rant‘ he’s nailing part of the charm of his work. As long as the rant was in place, no tune was too small, too jingly or too silly to make something worthwhile out of.

After Palace Of Swords Reversed I bought anything I could get my hands on. Luckily there was a  lot of it, and it was mostly pretty affordable, especially the stuff from the band’s then slightly maligned, now justly celebrated mid-80s period of relative commercial success. In itself, that success was odd and underlined just how unique the band, and specifically Smith’s vision, was. I loved that Mark E. Smith saw nothing elitist or strange about working with a ballet company, or in writing for the theatre and working with ‘serious’ artists and yet the people I knew who derided Morrissey as being “poncy” never seemed to think that about MES. The fact that he refused to separate the ‘high’ arts from his work with The Fall was so powerful. Everyone knows, for example, that Brian May is an astrophysicist, but imagine if astrophysics had somehow been indivisible from his work with Queen; they would have been far a more peculiar and far less successful, but also (with no offence intended to the band or its members) probably more interesting band.

lot of it, and it was mostly pretty affordable, especially the stuff from the band’s then slightly maligned, now justly celebrated mid-80s period of relative commercial success. In itself, that success was odd and underlined just how unique the band, and specifically Smith’s vision, was. I loved that Mark E. Smith saw nothing elitist or strange about working with a ballet company, or in writing for the theatre and working with ‘serious’ artists and yet the people I knew who derided Morrissey as being “poncy” never seemed to think that about MES. The fact that he refused to separate the ‘high’ arts from his work with The Fall was so powerful. Everyone knows, for example, that Brian May is an astrophysicist, but imagine if astrophysics had somehow been indivisible from his work with Queen; they would have been far a more peculiar and far less successful, but also (with no offence intended to the band or its members) probably more interesting band.

Although most of my favourite Fall albums are the early ones (especially Dragnet, Grotesque (After The Gramme) and Hex Enduction Hour) those 80s albums with the Mark and Brix-led lineup(s), especially The Wonderful and Frightening World Of The Fall are pretty unassailable and perhaps the least overtly commercial ‘commercial’ period of any band I can think of. The band stayed good though, and although I am not a Fall completist (a vocation rather than a hobby) I’ve found that any Fall record one picks up will have something great on it; and there aren’t many bands with a 40 year career you can say that about.

Although most of my favourite Fall albums are the early ones (especially Dragnet, Grotesque (After The Gramme) and Hex Enduction Hour) those 80s albums with the Mark and Brix-led lineup(s), especially The Wonderful and Frightening World Of The Fall are pretty unassailable and perhaps the least overtly commercial ‘commercial’ period of any band I can think of. The band stayed good though, and although I am not a Fall completist (a vocation rather than a hobby) I’ve found that any Fall record one picks up will have something great on it; and there aren’t many bands with a 40 year career you can say that about.

A few random but significant (to me) Mark E. Smith/Fall things:

- my favourite Fall release of them all is Slates (1981); typically awkward, it is a brilliantly ungainly 6-track 10″ which Mark E. Smith was proud of as it was too long to qualify for the singles chart but too short for the album chart; not that it was likely to trouble either one. Plus, it opens with MES shouting “Pink press threat!

- I must be impressionable; I think I got into Albert Camus because The Fall were named after one of his books.

- I don’t remember which music paper it was in, but Mark E. Smith was a guest reviewer in one of the weeklies c.1992 and gave Morrissey’s Your Arsenal a surprisingly positive(ish) review. One phrase that stuck in my memory (perhaps incorrectly) and seems definitively MES-ish to me is “the guitar player has too much equipment”

- When I first read (in the late 90s?) Christopher Isherwood’s autobiographical novel Lions And Shadows (1938) the idea of ‘The Other Town’, the sinister unseen parallel reality accessed through various apparently ordinary gates and doorways in Cambridge reminded me irresistibly of the band, especially the bizarre, creepy but also funny narrative songs like the (actually quite Lovecraftian) ‘Impression Of J. Temperance’ :

“A never seen dog breeder

This is the tale of his replica

Name was J. Temperance

Only two did not hate him

Because peasants fear local indifference

Pet shop and the vet, Cameron…”

- when I finally listened to the classic German band Can it was because the Fall song ‘I Am Damo Suzuki‘ made me curious about them

- one of the key things about The Fall’s music is its palate-cleansing quality; their music makes almost any other comparable popular music sound sentimental in comparison. And yet on the rare occasions (‘Bill Is Dead‘, ‘Edinburgh Man‘) when MES is sentimental the songs are among his best.

- ‘Edinburgh Man‘ was probably the first song I heard by a band I liked that was about a place I knew

- I have been a Fall fan for half of my life, but I’ve only met maybe 4 or 5 other people who like them (though I realise they are quite popular)

- I never particularly wanted to meet Mark E. Smith, but I’m very sad that he’s dead.

PS – the title for this piece is from an enigmatic line in the – obviously – highly peculiar song New Face In Hell:

The dead cannot contradict/Sometimes the living cannot