Firstly, the title comes from this short essay by one of my favourite historical figures, Rosa Luxemburg; it’s worth a read.

If anything demonstrates that half of the human race is in need of a special day to celebrate their achievements and raise awareness of the challenges they face, it’s the ongoing existence and high profile of International Women’s Day. I’m not here just to criticise it, so bear with me.

In a way it seems deeply patronising (not an accidental use of the word) that it even exists, since the celebration of IWD is in itself a sign that the patriarchy is in obnoxiously good health. Seems paradoxical, but look at the contrast between not just the profile of, but the nature of IWD, compared to International Men’s Day, which contrary to the belief of the frothing-at-the-mouth men on the misogynist fringe does exist (19 November), highlights the background that it exists against.

International Women’s Day commemorates the (ongoing) fight for Women’s rights, raises awareness of issues surrounding gender inequality and is a celebration of the achievements of women throughout the ages. International Men’s Day raises awareness of issues like suicide, self-harm, violence, homelessness etc; it’s a good thing, but it’s a much smaller and very different thing. Both international days are – necessarily – framed in the same way. The bad things that women have faced and continue to face – violent death, mutilation, violence, political, religious and social disenfranchisement – are the product of societies where women have been and in many ways continue to be second class citizens; the power structures they struggle with and against are overwhelmingly male and male-dominated. The problems that Men’s day raises, likewise come from men’s struggles to exist within that same socio-political/religious framework. The fact that I’ve spent half a paragraph about Women’s Day writing about Men’s Day is ironic but it’s also systemic.

Does that mean that IWD is a bad thing? Clearly not. There are women who, for a variety of reasons choose to denounce or simply opt out of the whole idea of it – as is their right – but the position of women has not improved so much over the past quarter century that the inequalities are merely historical, as seemed possible to envision around the end of the 1980s. And while the achievements of women in almost every field are acknowledged more now than ever, they are, depending on which sphere they take place in, often still seen as special cases; ‘women artists,’ ‘female plumbers’ etc, whereas terms from my childhood like ‘male nurse’ seem comically inappropriate (which isn’t to say that some people don’t still use them; but usually men, and for reactionary reasons).

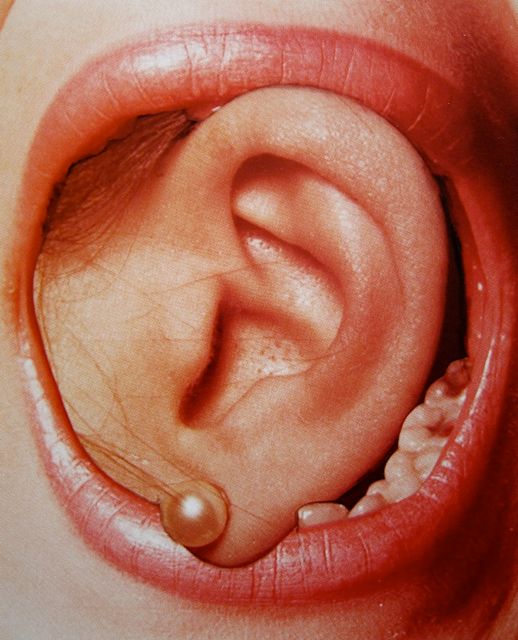

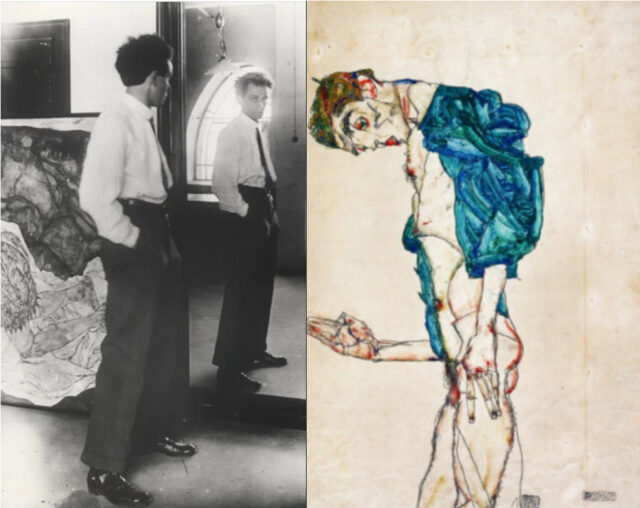

There’s also a valid argument that celebrating womens/mens days simply reinforces a binary that is merely a symptom of the old-fashioned, patriarchal system. It’s kind of undeniable; the name alone, International Women’s Day supposes “women” as a monolith. One of my favourite artists is the Surrealist Claude Cahun (born Lucie Schwob), whose work is often (by me, too) promoted as part of IWD celebrations of female artists, despite the artist’s unambiguous statement from Disavowals (1928) that “Neuter is the only gender that always suits me.” To ignore someone’s own personal identity in order to celebrate something about themselves that they specifically denied feels like a strange kind of tribute.

Nonetheless, nobody, not even Claude Cahun, denied that women do exist and that they have been and are (okay some people do loudly deny this bit) oppressed and subject to systemic inequalities.

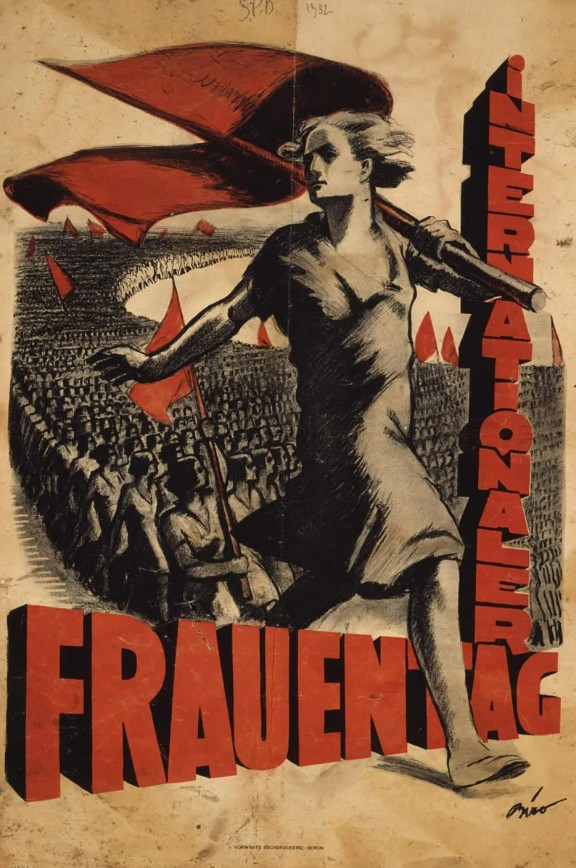

What’s often overlooked now too is that International Women’s Day was historically – though not consistently – a socialist celebration. See here for an excellent exploration of its radical origins. Working Women’s Day – the date 8th March was chosen by Lenin, fact fans – was originally tied to issues of Workers’ Rights and the fight for equality more widely, but even in the Soviet Union the image softened over the years until eventually it – ironically – came to celebrate women in traditional roles (mothers, wives) rather than revolutionary ones. Which is lame; but it’s easy to see why that link has eroded. The struggle for Women’s liberation was initially, and throughout its radical period in the 60s and 70s seen as analogous to the working class struggle – where women occupied a kind of working class, that is subordinate, position even within the working class. The gradual (but of course never total) amelioration of the rights of workers made aspects of the radicalism of the past feel dated and possibly unnecessary, though that is less true than it sometimes seems. Also, not all women were or are working class anyway, and class distinctions of that kind are not universal in every society in the world, but women’s marginalisation almost is.

Plus, people and perceptions change. My mother was a working class ‘Women’s Lib,’ Spare Rib-reading feminist of the 60s/70s, but although her views on Women’s liberation never really changed, from the 80s onwards she became puritanical in a way that now seems, to her children’s generation, a bit sexist, oddly. For example, she couldn’t see someone like Madonna (the popular entertainer, not the mother of Christ) and her ilk, however apparently empowered, as anything other than a manifestation of the retrograde desires of men, and she would probably have agreed with Morrissey that make-up is a lie, or even gone further to suggest that it’s a lie established by the patriarchy to keep women in their place. It’s a point of view, I suppose; but it’s also one that polices the image that women choose to project for themselves and so seems fundamentally anti-progressive, though I understand the logic of it.

Similarly, there are people who bemoan the loss of the ‘Class War’ aspect IWD, which I again understand, because I do think capitalism & patriarchy are bad and harmful to humanity in general and women in particular. But as a ‘working class’ male I also kind of reject it. Identifying with the system that labels you seems fundamentally unhelpful to me. I am ‘working class’ because that is the caste system established by a capitalist power structure, just as I would have been ‘peasant class’ centuries ago in a feudal society. Embracing that class identity seems far less attractive than altering society until its labels have no meaning anymore.

A fairer version of capitalism may not be the ultimate aim, but it would at least be a good thing. Marx’s ideal – I have a lot of time and affection for Marx, but I think he was often wrong, or at least that 21st century problems do not call for 19th century solutions – that inequality reaches crisis point so that revolution becomes a necessity feels to me very much like the apocalyptic thinking of those who want to immerse the world in war to bring about the second coming of Christ. The problem is – as we see, now, with war – that people, perhaps even generations of people, have to actually live their whole lives during that ‘crisis point’ which can continue, depending on the strength of the overarching system, almost indefinitely. Misery now, reward later is the self-serving bullshit the Christian church8 has been selling for 2000 years, I don’t think society is improved by adopting a well-meaning socialist version of it. Surely the life of even a single person is more important than the fulfilment of an ideology? Agree to disagree perhaps.

Which again has taken this away from International Women’s Day. When one is talking about half of the human race any kind of generalisation is bound to be wrong, but solidarity with people who are forced to struggle for equality as human beings within systems designed to keep them in a subordinate role never is.

It may be – especially in the social media age – that celebrations like International Women’s Day come under the banner of Bread and Circuses that the satirist Juvenal noted Imperial Rome offered to the people in lieu of the political power they held in the days of the old Republic. So should we get rid of them? No, would be my answer – quite the opposite, we should expand on them, turn them into actual holidays, raise awareness of every grievance that people have under a grossly unequal political system. If the ruling class of the Capitalist/Tech Oligarchy are offering circuses (where is the bread though?) to placate the people and keep them docile, then the very least their subjects can do to exert their will is to take over the circuses and to remake them in their own image, loud and unignorable.

Ah well, never mind, maybe soon there will be an International Humans Day where the (male) technocratic overlords agree to turn off AI for a day or something to show false solidarity with the rest of us. I won’t hold my breath though.

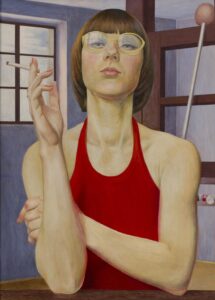

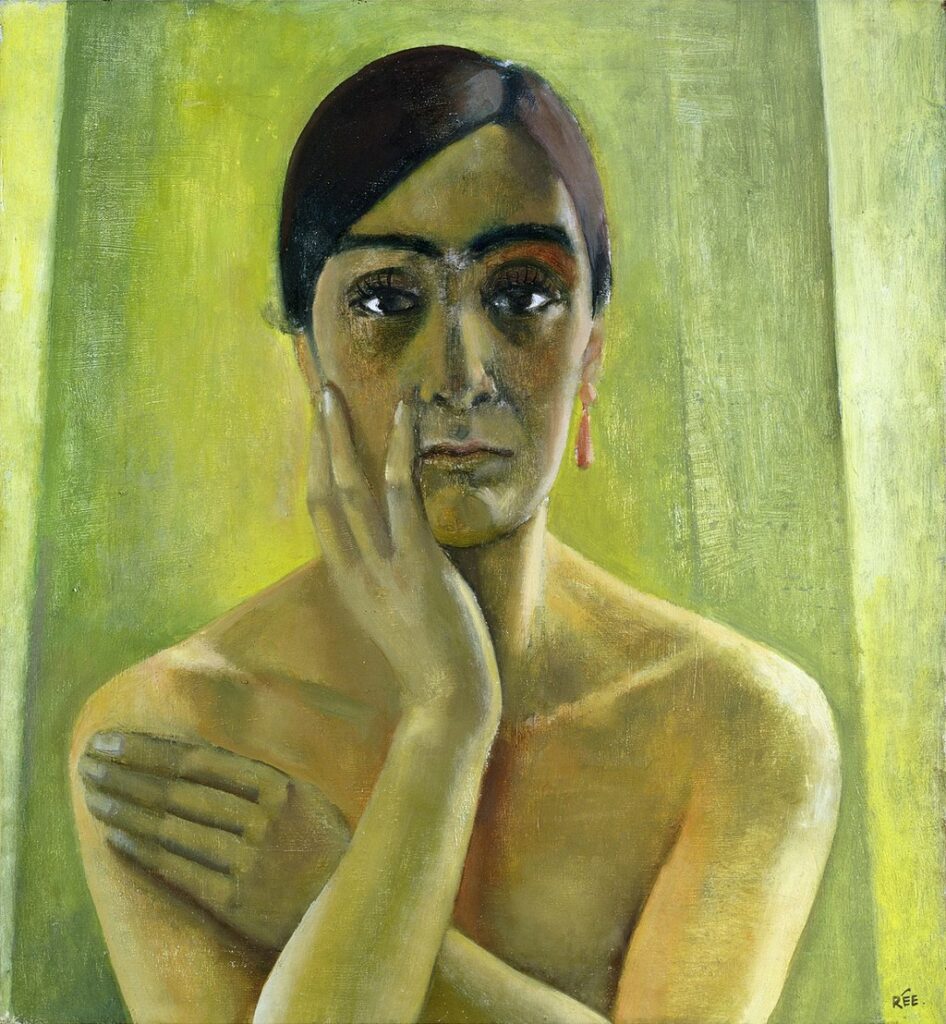

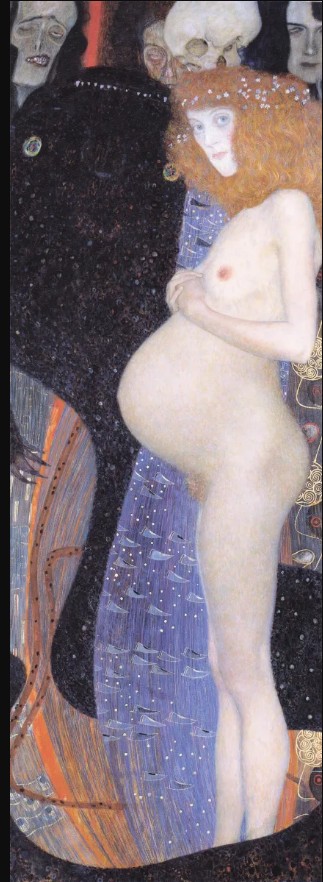

To end on something more positive, I’ve evangelised elsewhere about art history as a subject (here’s my one-line reason why everyone should study it; Art History is not just about the past, it encompasses everything that’s important about the present; politics, religion, gender, philosophy, personal, national and local identity – and studying the subject and freeing it from its historical assumptions and biases only makes it deeper and richer; plus you get to study fascinating, powerful and beautiful products of the human mind and body, too). Over the past decade or so the place of female artists within that history – and the profiles of individual women artists – has been explored more than ever before so that, although we are not yet at a point where women artists and male artists (and neither) just become ‘artists’ it’s no longer as unthinkable as that would have been when I studied art history 20 years ago.

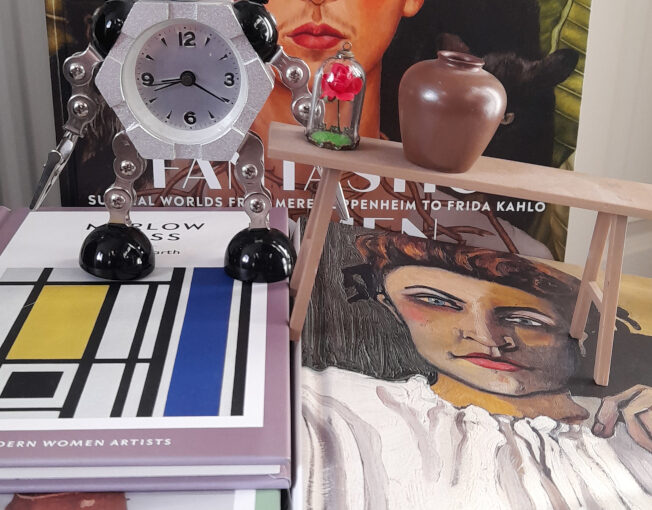

On a less exulted note, when I first started posting things on Instagram around a decade ago, books like Jennifer Higgie’s The Mirror and the Palette, Katie Hessel’s The Story of Art Without Men (2022), Eiderdown Books’ superb Modern Women Artists series, Phaidon’s Great Women Artists (2019) and (my favourite) Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters (2023) didn’t yet exist.

Some of my favourite artists – Jenny Saville, Hannah Höch, Gabriele Münter– were women and, like most female artists they made works that on one level transcend gender, as I think all great art does, but were also formed from an unmistakably female point of view (just as I would say Picasso’s art is unmistakably male). Female artists were, in short, making art that only female artists could make, (I’d actually go further and say that all great artists regardless of gender make art that only that individual can make, but that doesn’t change the basic point).

I found, and it’s still true, about art in general and not only – though especially – by women, that the more you look, the more you find and so when I started regularly posting art by female artists, most of whom were new to me, I began keeping a kind of database of artists and their birthdays. So here it is, in simplified form. There are many, many omissions (especially of sculptors – not so much my thing – and contemporary artists, whose birthdays are often not so easy to find) and it will always be a work in progress, but I think it’s worth sharing here anyway (and in birthday order, so you can see if you share your birthday with a fantastic artist; why not?) Happy International Women’s Day!.

JANUARY

Selma Gubin born 01-Jan 1905

Rita Kernn-Larsen born 01-Jan 1904

Lynette Yiadom-Boakye born 01-Jan 1977

Selma Plawneek-des Coudres born 02-Jan 1883

Slava Raskaj born 02-Jan 1877

Sylvi Kunnas born 03-Jan 1903

Maruja Mallo born 05-Jan 1902

Margaret Modlin born 05-Jan 1927

Madame Yevonde born 05-Jan 1893

Ruth Gikow born 06-Jan 1915

Sanja Ivekovic born 06-Jan 1949

Franciska Clausen born 07-Jan 1899

Fahrelnissa Zeid born 07-Jan 1901

Wanda von Debschitz-Kunowski born 08-Jan 1870

Alida Jantina Pott born 08-Jan 1888

Julie Wolfthorn born 08-Jan 1864

Tina Bauer-Pezellen born 09-Jan 1897

Annemarie Heinrich born 09-Jan 1912

Maxa Nordau born 10-Jan 1897

Nora Heysen born 11-Jan 1911

Marcia Marcus born 11-Jan 1928

Rosalba Carriera born 12-Jan 1673

Hannah Hirsch-Pauli born 13-Jan 1864

Lilla Cabot Perry born 13-Jan 1848

Alice Pike Barney born 14-Jan 1857

Berthe Morisot born 14-Jan 1841

Eve Sonneman born 14-Jan 1946

Louise Blair Daura born 15-Jan 1905

Sabine Lepsius born 15-Jan 1864

Gerta Overbeck born 16-Jan 1898

Teddy Røwde born 16-Jan 1911

Alexandra Ekster born 18-Jan 1882

Cindy Sherman born 19-Jan 1954

Marianne Stokes born 19-Jan 1855

Sophie Tauber-Arp born 19-Jan 1889

Leyly Matine-Daftary born 19-Jan 1937

Maxine Albro born 20-Jan 1893

Hertha Spielberg born 21-Jan 1890

Annemarie Jacob born 22-Jan 1891

Kiki Kogelnik born 22-Jan 1935

Maria Luiko born 25-Jan 1904

Emilie von Hallavanya born 26-Jan 1874

Katarzyna Kobro born 26-Jan 1898

Yva (Else Ernestine Neulander-Simon) born 26-Jan 1900

Jeanne Selmersheim-Desgrange born 27-Jan 1877

Maria Tlusty born 27-Jan 1901

Bertha Muller born 28-Jan 1848

Alice Neel born 28-Jan 1900

Elisabeth Büchsel born 29-Jan 1867

Anna Susanna Fries born 30-Jan 1827

Teresa Feoderovna Ries born 30-Jan 1874

Amrita Sher-Gil born 30-Jan 1913

Masa Feszty born 31-Jan 1894

Elena Liessner-Blomberg born 31-Jan 1897

Cornelia Macintyre Foley born 31-Jan 1909

FEBRUARY

Doris Lee born 01-Feb 1905

Kris Torne born 01-Feb 1867

Sybil Atteck born 03-Feb 1911

Helen Forbes born 03-Feb 1891

Henriette Petit born 03-Feb 1894

Katherine Read born 03-Feb 1723

Georgina de Albuquerque born 04-Feb 1885

Marthe Hirt born 04-Feb 1890

Minna Köhler-Roeber born 04-Feb 1883

Ksenia Boguslavskaya born 05-Feb 1892

Jeanne Bieruma Oosting born 05-Feb 1898

Dorothea Maetzel-Johannsen born 06-Feb 1886

Arte Topalian born 06-Feb 1906

Kaete Lassen born 07-Feb 1880

Paula Modersohn-Becker born 08-Feb 1876

Anita Ree born 09-Feb 1885

Celia Calderon born 10-Feb 1921

Eva Frankfurther born 10-Feb 1930

Dorte Clara Wolff (Dodo) born 10-Feb 1907

Annelise Kretschmer born 11-Feb 1903

Léa Lafugie born 11-Feb 1890

Kate Diehn-Bitt born 12-Feb 1900

Marie Vassilieff born 12-Feb 1884

Marta Hegemann born 14-Feb 1894

Marie Vorobieff (Marevna) born 14-Feb 1892

Dora de la Torre born 14-Feb 1924

Mary Adshead born 15-Feb 1904

Grethe Jurgens born 15-Feb 1899

Gertrude Abercrombie born 17-Feb 1909

Greta Hällfors-Sipilä born 19-Feb 1899

Hazel Janicki born 19-Feb 1918

Gabriele Munter born 19-Feb 1877

Else Berg born 19-Feb 1877

Maria von Heider-Schweinitz born 20-Feb 1894

Lía Correa Morales born 20-Feb 1893

Grace Carpenter Hudson born 21-Feb 1865

Delhy Tejero born 22-Feb 1904

Gundula Schulze Eldowy born 23-Feb 1954

Martha Cunz born 24-Feb 1876

Alice Bailly born 25-Feb 1872

Broncia Koller-Pinnell born 25-Feb 1863

Hilde Hamann born 26-Feb 1898

Alexandra Povorina born 26-Feb 1885

Annie Swynnerton born 26-Feb 1844

Teresa Condeminas i Soler born 27-Feb 1905

Eva-Maria Bergmann born 28-Feb 1941

Julia Thecla born 28-Feb 1896

MARCH

Marcelle Cahn born 01-Mar 1895

Erika Streit born 01-Mar 1910

Lola Cueto born 02-Mar 1897

Agda Holst born 02-Mar 1886

Judith Alpi born 03-Mar 1893

Gussy Hippold-Ahnert born 03-Mar 1910

Anne Ratkowski born 03-Mar 1903

Ellen Emmet Rand born 04-Mar 1875

Charmion Von Wiegand born 04-Mar 1896

Gertrude Fehr born 05-Mar 1895

Clara Ledesma Terrazas born 05-Mar 1924

Maria Blanchard born 06-Mar 1881

Pauline Boty born 06-Mar 1938

Maria Uhden born 06-Mar 1892

Marisa Roesset Velasco born 06-Mar 1904

Aenne Biermann born 08-Mar 1898

Constance Mayer born 09-Mar 1774

Annalize Pilasik born 10-Mar 1903

Rita Angus born 12-Mar 1908

Zofia Atteslander born 12-Mar 1874

Elaine De Kooning born 12-Mar 1918

Marie Eberhard born 12-Mar 1897

Idelle Weber born 12-Mar 1932

Lizzy Ansingh born 13-Mar 1875

Andree Bosquet born 13-Mar 1900

Diane Arbus born 14-Mar 1923

Annemarie von Jakimow-Kruse born 14-Mar 1889

Maria Slavona born 14-Mar 1865

Mary Pratt born 15-Mar 1935

Gerda Wegener born 15-Mar 1886

Maria Austria born 19-Mar 1915

Marie Ellenrieder born 20-Mar 1791

Renee Sintenis born 20-Mar 1888

Alix Ayme born 21-Mar 1894

Greta Kempton born 22-Mar 1901

Lea Grundig born 23-Mar 1906

Marie Howet born 24-Mar 1897

Charley Toorop born 24-Mar 1891

Petrona Viera born 24-Mar 1895

Therese Debains born 25-Mar 1897

Johanna Kampmann-Freund born 25-Mar 1888

Käthe Loewenthal born 27-Mar 1878

Elga Sesemann born 28-Mar 1922

Dora Carrington born 29-Mar 1893

Cecile Walton born 29-Mar 1891

Helene Riedel born 30-Mar 1901

APRIL

Gertrude Bohnert born 02-Apr 1908

Emilie Charmy born 02-Apr 1878

Stella Snead born 02-Apr 1910

Hermine Aichenegg born 03-Apr 1915

Francesca woodman born 03-Apr 1958

Constance Marie Charpentier born 04-Apr 1767

Ruth Smith born 05-Apr 1913

Leonora Carrington born 06-Apr 1917

Jeanne Hebuterne born 06-Apr 1898

Kata Kalivoda born 06-Apr 1877

Hilde Rubinstein born 07-Apr 1904

Lilly Steiner born 07-Apr 1884

Annemirl Bauer born 10-Apr 1939

Gunvor Gronvik born 10-Apr 1912

Frances Foy born 11-Apr 1890

Adélaïde Labille-Guiard born 11-Apr 1749

Maggie Laubser born 14-Apr 1886

Olga Boznanska born 15-Apr 1865

Elizabeth Catlett born 15-Apr 1915

Princess Elisabeth Vilma Lwoff-Parlaghy born 15-Apr 1863

Laura Alma-Tadema born 16-Apr 1852

Inji Efflatoun born 16-Apr 1924

Charlotte Salomon born 16-Apr 1917

Hermine David born 19-Apr 1886

Eva Gonzales born 19-Apr 1849

Dod Procter born 21-Apr 1890

Raquel Forner born 22-Apr 1902

Ottilie Roederstein born 22-Apr 1859

Lee Miller born 23-Apr 1907

Christine Bacheler Nisbet born 24-Apr 1902

Lyubov Popova born 24-Apr 1889

Bridget Riley born 24-Apr 1931

Mary Brandt (Perez) born 25-Apr 1917

Mela Muter born 26-Apr 1876

Doro Ording born 26-Apr 1901

Nathalie Kraemer born 28-Apr 1891

Else Fischer-Hansen born 29-Apr 1905

Mainie Jellett born 29-Apr 1897

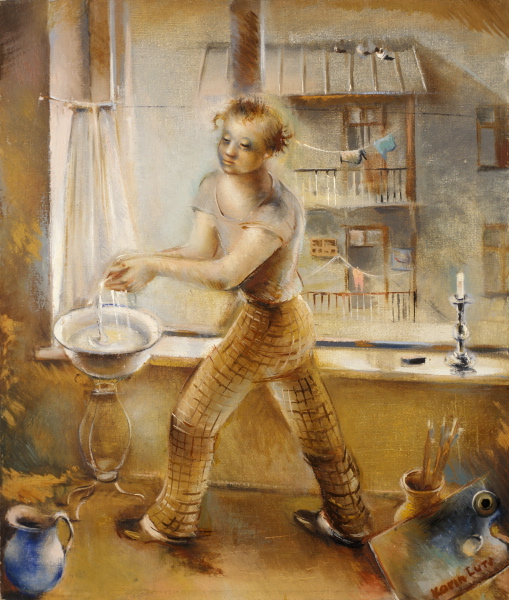

Karin Luts born 29-Apr 1904

Ruth Meier born 29-Apr 1888

Juana Romani born 30-Apr 1867

Thea Schleusner born 30-Apr 1879

Joronn Sitje born 30-Apr 1897

MAY

Cecilia Beaux born 01-May 1855

Romaine Brooks born 01-May 1874

Elsa Thoresen born 01-May 1906

Eva Aeppli born 02-May 1925

Peggy Bacon born 02-May 1895

Chinwe Chukwuogo-Roy born 02-May 1952

Brigitte Fugmann born 03-May 1948

Stina Forssell born 03-May 1906

Geta Bratescu born 04-May 1926

Sylvia Pankhurst born 05-May 1882

Celeste Woss y Gil born 05-May 1891

Lucie Citti Ferreira born 06-May 1911

Suzy Freylinghuysen born 07-May 1911

Marion Gilmore born 07-May 1909

Dore Meyer-Vax born 08-May 1908

Felicita Pauluka born 08-May 1925

Paula Gans born 09-May 1883

Stanislawa de Karlowska born 09-May 1876

Hanna Klose-Greger born 09-May 1892

Grete Stern born 09-May 1904

Frida Konstantin born 10-May 1884

Helene von Taussig born 10-May 1879

Eva Schulze Knabe born 11-May 1907

Ilske Schwimmer born 11-May 1915

Monika Brachmann born 12-May 1944

Paula Lauenstein born 12-May 1898

Charlotte Wankel born 12-May 1888

Sara Afonso/Affonso born 13-May 1899

Louise Seidler born 15-May 1786

Stella Bowen born 16-May 1893

Tamara de Lempicka born 16-May 1898

Laura Wheeler Waring born 16-May 1887

Bele Bachem born 17-May 1916

June Beer born 17-May 1935

Martha Bernstein born 17-May 1874

Kati Horna born 19-May 1912

Clara von Rappard born 19-May 1857

Ellen Auerbach born 20-May 1906

Lily Furedi born 20-May 1896

Margret Hofheinz-Döring born 20-May 1910

Maria Hiller-Foell born 21-May 1880

Marisol Escobar born 22-May 1930

Erszebet Korb born 22-May 1889

Julia Diaz born 23-May 1917

Charlotte Berend-Corinth born 25-May 1880

Anita Magsaysay-Ho born 25-May 1914

Vally Wieselthier born 25-May 1895

Fanny Harlfinger-Zakucka born 26-May 1873

Amelie Lundahl born -May 1850

Heidi Vogel born 27-May 1951

Anna De Weert born 27-May 1867

Anna-Eva Bergman born 29-May 1909

Marlow Moss born 29-May 1889

Vanessa Bell born 30-May 1879

Audrey Flack born 30-May 1931

Magdalena Mira Mena born 30-May 1859

Carmen Herrera born 31-May 1915

Mireya Lafuente born 31-May 1905

Hilla von Rebay born 31-May 1890

JUNE

Vera Nilsson born 01-Jun 1888

Lotte B Prechner born 01-Jun 1877

Greta Gerell born 02-Jun 1898

Louise Amans born 05-Jun 1850

Winifred Knights born 05-Jun 1899

Biruta Baumane born 06-Jun 1922

Ricarda Jacobi born 07-Jun 1923

Laura Rodig born 07-Jun 1901

Alice Rahon born 08-Jun 1904

Montserrat Gudiol born 09-Jun 1933

Oda Krohg born 11-Jun 1860

Priscilla Warren Roberts born 13-Jun 1916

Pan Yuliang born 14-Jun 1895

Agnes Tait born 14-Jun 1894

Erna Lincke born 15-Jun 1899

Edith Meyer von Kamptz born 15-Jun 1884

Fritzi Brod born 16-Jun 1900

Henriette Browne born 16-Jun 1829

Irma Lang-Scheer born 17-Jun 1901

Margarete Kubicka born 20-Jun 1891

Emilia Bertole born 21-Jun 1896

Gwen John born 22-Jun 1876

Wangechi Mutu born 22-Jun 1972

Hilde Rakebrand born 22-Jun 1901

Olga Rozanowa born 22-Jun 1886

Madge Tennent born 22-Jun 1889

Lilo Raymond born 23-Jun 1922

Elena Shegal born 23-Jun 1924

Meraud Guinness born 24-Jun 1904

Helen Lundeberg born 24-Jun 1908

Alice Frey born 25-Jun 1895

Kay Sage born 25-Jun 1898

Vilma Eckl born 26-Jun 1892

Coba Ritsema born 26-Jun 1876

Helene Perdriat born 27-Jun 1889

Catherine Yarrow born 27-Jun 1904

Ali Goubitz born 28-Jun 1904

Florence Henri born 28-Jun 1893

Nan Youngman born 28-Jun 1906

Hannelore Neumann-Tachilzik born 29-Jun 1939

JULY

Herminia Arrate born 01-Jul 1896

Elizabeth Lochrie born 01-Jul 1890

Prudence Heward born 02-Jul 1896

Lydia Mei born 02-Jul 1896

Rahel Szalit-Marcus born 02-Jul 1894

Georgina Klitgaard born 03-Jul 1893

Petra Flemming born 06-Jul 1944

Frida Kahlo born 06-Jul 1907

Unica Zurn born 06-Jul 1916

Artemisia Gentileschi born 08-Jul 1593

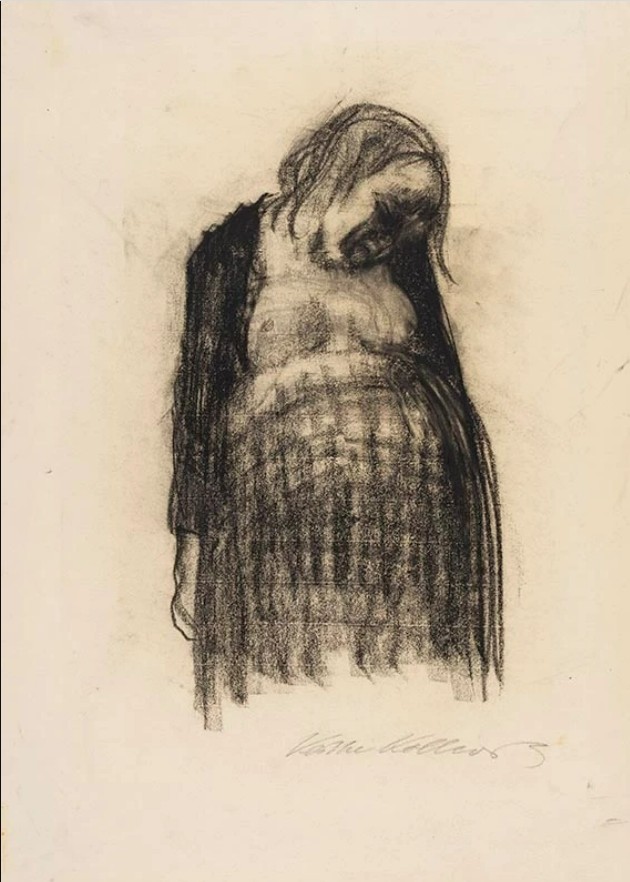

Kathe Kollwitz born 08-Jul 1867

Carmen Mondragon (Nahui Olin) born 08-Jul 1894

Maria Tupper Hunneus born 09-Jul 1893

Helene Schjerfbeck born 10-Jul 1862

Luise Kornsand born 11-Jul 1876

Bertina Lopes born 11-Jul 1924

Ruth Starr Rose born 12-Jul 1887

Honore Desmond Sharrer born 12-Jul 1920

Helene Arnau born 13-Jul 1870

Alice Brasse-Forstmann born 13-Jul 1903

Elena Huerta Muzquiz born 15-Jul 1908

Giselle Kuster born 15-Jul 1911

Berenice Abbott born 17-Jul 1898

Marie Petiet born 20-Jul 1854

Marta Astfalck-Vietz born 21-Jul 1901

Greta Freist born 21-Jul 1904

Maral Rahmanzadeh born 23-Jul 1916

Anna Dorothea Therbusch born 23-Jul 1721

Wanda Wulz born 25-Jul 1903

Alba Calderon (de Gil) born 27-Jul 1908

Nelly van Doesburg born 27-Jul 1899

Sofia Bassi born 28-Jul 1913

Mathilda Rotkirch born 28-Jul 1813

Anna Stainer-Knittel born 28-Jul 1841

Grace Pailthorpe born 29-Jul 1883

Bettina Shaw-Lawrence born 29-Jul 1921

Friedl Dicker-Brandeis born 30-Jul 1898

Maria Szantho born 31-Jul 1897

Doris Zinkeisen born 31-Jul 1897

AUGUST

Rachel Baes born 01-Aug 1912

Ida Gerhardi born 02-Aug 1862

Gretel Haas-Gerber born 02-Aug 1903

Maria Wiik born 03-Aug 1853

Laura Knight born 04-Aug 1877

Hedda Sterne born 04-Aug 1910

Edith Dettmann born 04-Aug 1898

Margit Graber born 05-Aug 1895

Irene Rice Pereira born 05-Aug 1902

Macena Barton born 07-Aug 1901

Maria Caspar-Filser born 07-Aug 1878

Lili Orszag born 08-Aug 1926

Tove Jansson born 09-Aug 1914

Eliane de Meuse born 09-Aug 1899

Cornelia Paczka-Wagner born 09-Aug 1864

Rogi Andre born 10-Aug 1900

Margret Bilger born 12-Aug 1904

Marianne Fieglhuber-Gutscher born 12-Aug 1889

Nola Hatterman born 12-Aug 1899

Ernestine von Kirchsberg born 12-Aug 1857

Helene Roth born 12-Aug 1887

Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein) born 13-Aug 1895

Xenia Cage born 15-Aug 1913

Marie Goth born 15-Aug 1887

Zsuzsi Robos born 15-Aug 1929

Tamara Natalie Madden born 16-Aug 1975

Käthe Ephraim Marcus born 16-Aug 1892

Gunnvor Advocaat born 17-Aug 1912

Gudrun Petersdorff born 17-Aug 1955

Anna Ancher born 18-Aug 1859

Kyra Markham born 18-Aug 1891

Florine Stettheimer born 19-Aug 1871

Lette Valeska born 20-Aug 1885

Hedwig Holtz-Sommer born 22-Aug 1901

Agnes Lawrence Pelton born 22-Aug 1881

Ebba Carstensen born 23-Aug 1885

Agnes Cleve born 23-Aug 1876

Hannah Frank born 23-Aug 1908

Mariette Lydis born 24-Aug 1887

Henriette Paula Häberlin born 25-Aug 1882

Dorothea Tanning born 25-Aug 1910

Fanny Rabel born 27-Aug 1922

Olga Costa born 28-Aug 1913

Else Lohmann born 29-Aug 1897

Sughra Rababi born 29-Aug 1922

Martha Schrag born 29-Aug 1870

Anna Zinkeisen born 29-Aug 1901

Siri Deckert born 30-Aug 1888

Leonor Fini born 30-Aug 1907

Amy Sherald born 30-Aug 1973

Ida Kerkovius born 31-Aug 1879

SEPTEMBER

Adriana Bisi Fabbri born 01-Sep 1881

Mario Miguel Mollari 01-Sep 1930

Hilda Rix Nicholas born 01-Sep 1884

Augusta Roszmann born 01-Sep 1859

Mina Carlson-Bredberg born 02-Sep 1857

Else Meidner born 02-Sep 1901

Elin Danielson-Gambogi born 03-Sep 1861

Helene Funke born 03-Sep 1869

Lis Bertram-Ehmsen born 05-Sep 1897

Piti (Francis) Bartolozzi born 06-Sep 1908

Marie-Gabrielle Capet born 06-Sep 1761

Rosa Rolanda born 06-Sep 1896

Hanna Bekker vom Rath born 07-Sep 1893

Maria Lassnig born 08-Sep 1919

Mimi Parent born 08-Sep 1924

Anna Walinska born 08-Sep 1906

Aurora Reyes Flores born 09-Sep 1908

Consuelo Remedios González del Bianco born 10-Sep 1911

Marianne von Werefkin born 10-Sep 1860

Bona di Mandiargues born 12-Sep 1926

Nan Goldin born 12-Sep 1953

Lili Pancu born 13-Sep 1908

Eva Cederström born 15-Sep 1909

Hope Gangloff born 15-Sep 1974

Rosalie Gwathmey born 15-Sep 1908

Cordelia Urueta Sierra born 16-Sep 1908

Alla Horska born 18-Sep 1929

Maud Sulter born 19-Sep 1960

Hilda Belcher born 20-Sep 1881

Denise Bellon born 20-Sep 1902

Genevieve Springston Lynch born 20-Sep 1891

Else Hagen born 21-Sep 1914

Toyen born 21-Sep 1902

Anne Winterer born 21-Sep 1894

Hansl Bock born 22-Sep 1893

Irena Rüther-Rabinowicz born 22-Sep 1900

Esphyr Slobodkina born 22-Sep 1908

Suzanne Van Damme born 22-Sep 1901

Suzanne Valadon born 23-Sep 1865

Maina-Miriam Munsky born 24-Sep 1943

Tilsa Tsuchiya 24-Sep 1928

Marguerite Zorach born 25-Sep 1887

Suzi Gablik born 26-Sep 1934

Arcangela Paladini born 29-Sep 1596

OCTOBER

Marianne Brandt born 01-Oct 1893

Alice Prin (Kiki de Montparnasse) born 02-Oct 1901

Elisabeth Sophie Cheron born 03-Oct 1648

Kathleen Walne born 03-Oct 1915

Ester Ellqvist born 04-Oct 1880

Ellen Thesleff born 05-Oct 1869

Graciela Aranis born 06-Oct 1908

Meret Oppenheim born 06-Oct 1913

Nina Arbore born 08-Oct 1889

Elise Ransonnet-Villez born 08-Oct 1843

Faith Ringgold born 08-Oct 1930

Louise Rösler born -Oct 1907

Ithell Colquhoun born 09-Oct 1906

Zelia Salgado born 10-Oct 1904

Linda Kogel born 11-Oct 1861

Grete Csaki-Copony born 12-Oct 1893

Paula Deppe born 12-Oct 1886

Nadezhda Petrovic born 12-Oct 1873

Ruth Bernhard born 14-Oct 1905

Vilma Vrbova born 14-Oct 1905

Minna Citron born 15-Oct 1896

Lilly Hildebrandt born 16-Oct 1887

Elisabeth Chaplin born 17-Oct 1890

Cata Dujšin-Ribar born 17-Oct 1897

Agnes van den Brandeler born 18-Oct 1918

Jeanne Mandello born 18-Oct 1907

Bettina von Arnim born 19-Oct 1940

Jacqueline Marval born 19-Oct 1866

Ottilie Reylaender born 19-Oct 1882

Else-Christie Kielland born 20-Oct 1903

Gustava Engels von Veith born 20-Oct 1879

Penny Slinger born 21-Oct 1947

Lygia Clark born 23-Oct 1920

Rina Lazo (Wasem) born 23-Oct 1923

Marie-Louise von Motesiczky born 24-Oct 1906

Claude Cahun born 25-Oct 1894

Katalin Ladik born 25-Oct 1942

Ruth Light Braun born 26-Oct 1906 2003 oa

Marthe Donas born 26-Oct 1885 1967 oa

Bep Rietveld born 26-Oct 1913 1999 oa

Blanche-Augustine Camus born 27-Oct 1884

Julie Hagen-Schwarz born 27-Oct 1824

Sigrid Hjerten born 27-Oct 1885

Mary Moser born 27-Oct 1744

Paraskeva Clark born 28-Oct 1898

Bertha Müller born 28-Oct 1848

Alice Lex-Nerlinger born 29-Oct 1893

Louise Abbema born 30-Oct 1853

Maria Izquierdo born 30-Oct 1902

Angelika Kauffmann born 30-Oct 1741

Erna Schmidt-Carroll born 30-Oct 1896

Marie-Laure de Noailles born 31-Oct 1902

Marie Laurencin born 31-Oct 1883

Jóhanna Kristín Yngvadóttir born 31-Oct 1953

NOVEMBER

Hannah Hoch born 01-Nov 1889

Hedwig Woermann born 01-Nov 1879

Venny Soldan-Brofeldt born 02-Nov 1863

Lois Mailou Jones born 03-Nov 1905

Lilias Torrance Newton born 03-Nov 1896

Charlotte Buresova born 04-Nov 1904

Elena Luksch-Makowsky born 04-Nov 1878

Milena Pavlovic-Barili born 05-Nov 1909

Ann Brockman born 06-Nov 1899

Elsa Haensgen-Dingkuhn born 07-Nov 1898

Sonja Kovačić – Tajčević born 07-Nov 1894

Angeles Santos Torroella born 07-Nov 1911

Elizabeth Sparhawk-Jones born 08-Nov 1885

Emmy Bridgwater born 10-Nov 1906 1999 oa

Lisette Model born 10-Nov 1901

Debora Arango born 11-Nov 1907

Carry Hess born 11-Nov 1889

Magda Langenstraß-Uhlig born 11-Nov 1888

Mary Kessell born 13-Nov 1914

Ekaterina Savova-Nenova born 13-Nov 1901

Sonia Delaunay born 14-Nov 1885

Julie Manet born 14-Nov 1878

Tina Blau born 15-Nov 1845

Miriam Schapiro born 15-Nov 1923

Elisa Counis born 16-Nov 1812

Katharina Sieverding born 16-Nov 1944

Louise Dahl-Wolfe born 19-Nov 1895

Lily Harmon born 19-Nov 1912

Marianne Breslauer born 20-Nov 1909

Angelika Hoerle born 20-Nov 1899

Germaine Krull born 20-Nov 1897

Elisabeth Jerichau-Baumann born 21-Nov 1819

Jeanne Mammen born 21-Nov 1890

Dora Maar born 22-Nov 1907

Bridget Bate Tichenor born 22-Nov 1917

Else Hertzer born 24-Nov 1884

Mary Foote born 25-Nov 1872

Sara Shamma born 26-Nov 1975

Audrey Buller born 27-Nov 1902

Gretchen Wohlwill born 27-Nov 1878

Mabel Alvarez born 28-Nov 1891

Hedwig Marquardt born 28-Nov 1884

Else Wex-Cleemann born 29-Nov 1890

Fridel Dethleffs-Edelmann born 30-Nov 1899

DECEMBER

Eileen Agar born 01-Dec 1899

Jenny Mucchi-Wiegemann born 01-Dec 1895

Emilie Mediz-Pelikan born 02-Dec 1861

Marion Adnams born 03-Dec 1898

Dorte Helm born 03-Dec 1898

Grace English born 04-Dec 1891

Elfriede Lohse-Wächtler born 04-Dec 1899

Louise Catherine Breslau born 06-Dec 1856

Margaret Brundage born 09-Dec 1900

Louise de Hem born 10-Dec 1866

Zinaida Serebriakova born 10-Dec 1884

Olga Terri born 10-Dec 1916

Irène Zurkinden born 11-Dec 1909

Alison Watt born 11-Dec 1965 alive

Ragnhild Keyser born 12-Dec 1889

Emily Carr born 13-Dec 1871

Alice Sommer born 13-Dec 1898

Aino Bach born 14-Dec 1901

Remedios Varo born 16-Dec 1908

Bertha Wegmann born 16-Dec 1846

Suze Robertson born 17-Dec 1855

Jane Graverol born 18-Dec 1905

Ewa Kierska born 18-Dec 1923

Lucie Cousturier born 19-Dec 1876

Therese Schwartze born 20-Dec 1851

Trude Fleischmann born 22-Dec 1895

Margit Anna born 23-Dec 1913

Luvena Buchanan Vysekal born 23-Dec 1873

Alma del Banco born 24-Dec 1862

Sigrid Maria Schauman born 24-Dec 1877

Dorothy Johnstone born 25-Dec 1892

Ragnhild Kaarbo born 26-Dec 1889

Stella Steyne born 26-Dec 1907

Augusta von Zitzewitz born 26-Dec 1880

Annott (Jacobi) born 27-Dec 1894

Aisha Galimbaeva born 29-Dec 1917

Adela ber Vukić born 30-Dec 1888

Lucile Blanch born 31-Dec 1895

Beatrice Mandelman born 31-Dec 1912

2023 was the usual mixed bag of things; I didn’t see any of the big movies of

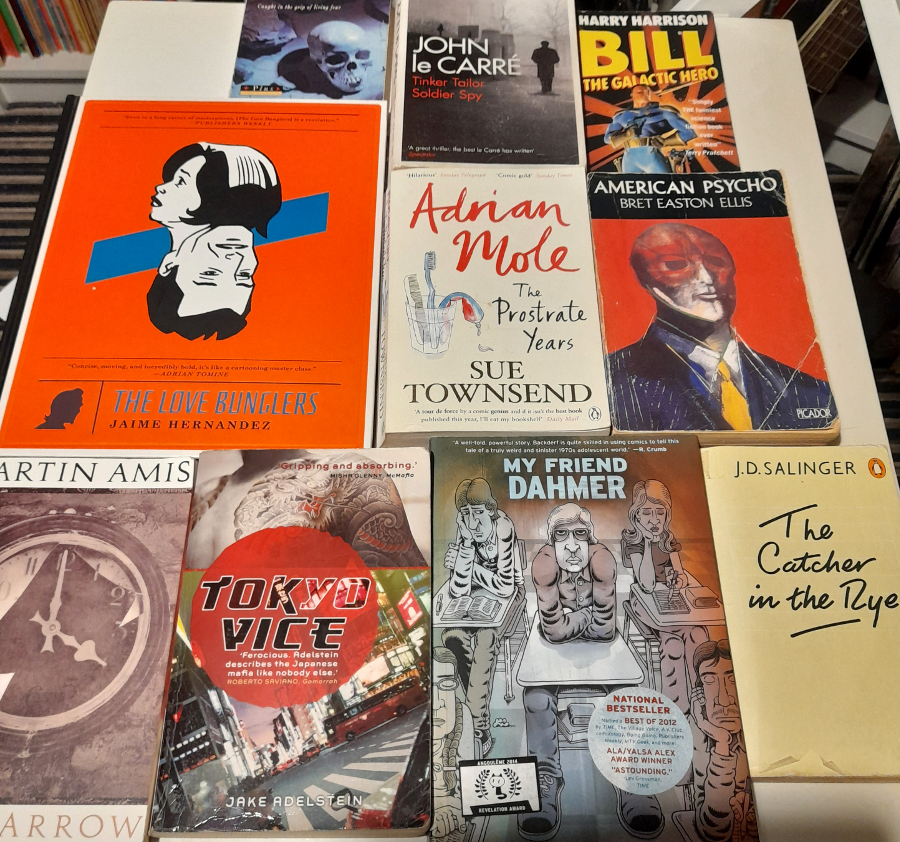

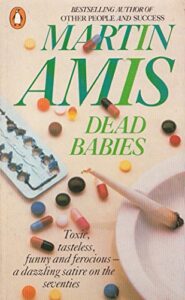

2023 was the usual mixed bag of things; I didn’t see any of the big movies of the year yet. I have watched half of Saltburn, which so far makes me think of the early books of Martin Amis, especially Dead Babies (1975) and Success (1978) – partly because I read them again after he died last year. They are both still good/nasty/funny, especially Success, but whereas I find that having no likeable characters in a book is one thing, and doesn’t stop the book from being entertaining, watching unlikeable characters in a film is different – more like spending time with actual unlikeable people, perhaps because – especially in a film like Saltburn – you can only guess at their motivations and inner life. So, the second half of Saltburn remains unwatched – but I liked it enough that I will watch it.

the year yet. I have watched half of Saltburn, which so far makes me think of the early books of Martin Amis, especially Dead Babies (1975) and Success (1978) – partly because I read them again after he died last year. They are both still good/nasty/funny, especially Success, but whereas I find that having no likeable characters in a book is one thing, and doesn’t stop the book from being entertaining, watching unlikeable characters in a film is different – more like spending time with actual unlikeable people, perhaps because – especially in a film like Saltburn – you can only guess at their motivations and inner life. So, the second half of Saltburn remains unwatched – but I liked it enough that I will watch it.

I read lots of good books in 2023 – I started keeping a list but forgot about it at some point – but the two that stand out in my memory as my favourites are both non-fiction. Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art is completely engrossing and full of exciting ways of really looking at pictures. I wrote at length about Elena Kostyuchenko’s I Love Russia

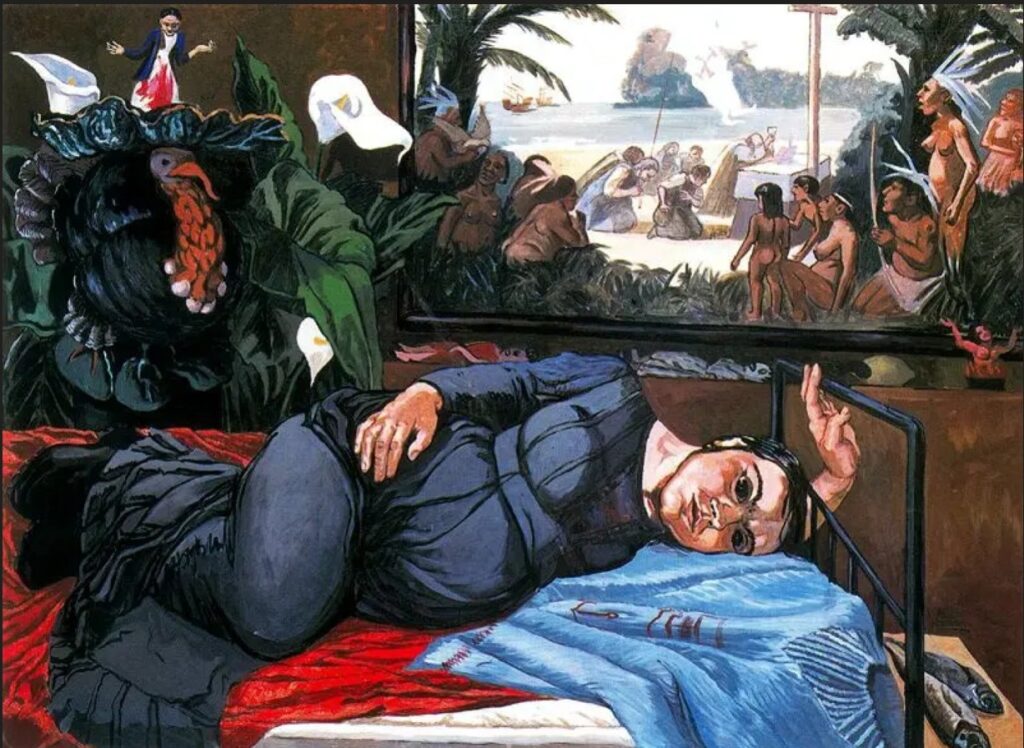

I read lots of good books in 2023 – I started keeping a list but forgot about it at some point – but the two that stand out in my memory as my favourites are both non-fiction. Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art is completely engrossing and full of exciting ways of really looking at pictures. I wrote at length about Elena Kostyuchenko’s I Love Russia  It’s no great surprise to me that my favourite books of the year would be – like much of my favourite art – by women. Though I think the individual voice is crucial in all of the arts, individuals don’t grow in a vacuum and because female (and, more widely, non-male) voices and viewpoints have always been overlooked, excluded, marginalised and/or patronised, women and those outside of the standard, traditional male authority figures more generally, tend to have more interesting and insightful perspectives than the ‘industry standard’ artist or commentator does. The first time that thought really struck me was when I was a student, reading about Berlin Dada and finding that Hannah Höch was obviously a much more interesting and articulate artist than (though I love his work too) her partner Raoul Hausmann, but that Hausmann had always occupied a position of authority and a reputation as an innovator, where she had little-to-none. And the more you look the more you see examples of the same thing. In fact, because women occupied – and in many ways still occupy – more culturally precarious positions than men, that position informs their work – thinking for example of artists like Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage or – a bigger name now – Frida Kahlo – giving it layers of meaning inaccessible to – because unexperienced by – their male peers.

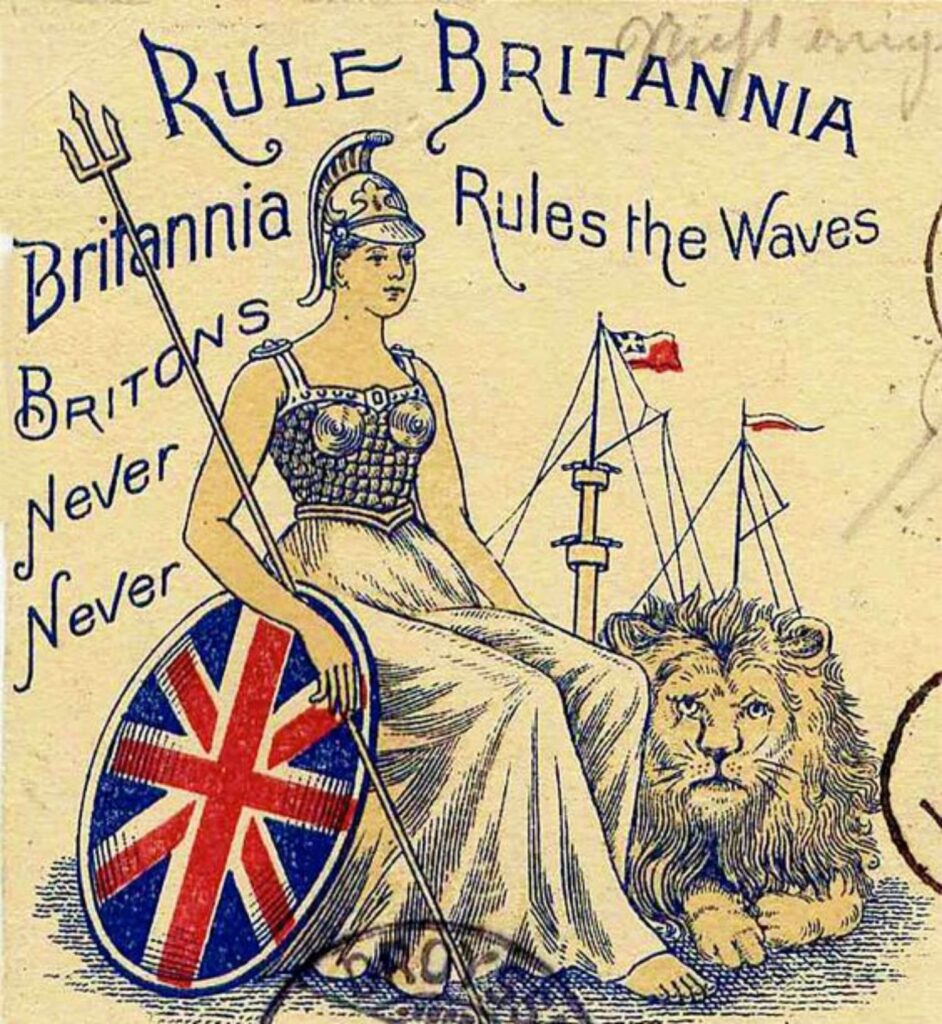

It’s no great surprise to me that my favourite books of the year would be – like much of my favourite art – by women. Though I think the individual voice is crucial in all of the arts, individuals don’t grow in a vacuum and because female (and, more widely, non-male) voices and viewpoints have always been overlooked, excluded, marginalised and/or patronised, women and those outside of the standard, traditional male authority figures more generally, tend to have more interesting and insightful perspectives than the ‘industry standard’ artist or commentator does. The first time that thought really struck me was when I was a student, reading about Berlin Dada and finding that Hannah Höch was obviously a much more interesting and articulate artist than (though I love his work too) her partner Raoul Hausmann, but that Hausmann had always occupied a position of authority and a reputation as an innovator, where she had little-to-none. And the more you look the more you see examples of the same thing. In fact, because women occupied – and in many ways still occupy – more culturally precarious positions than men, that position informs their work – thinking for example of artists like Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage or – a bigger name now – Frida Kahlo – giving it layers of meaning inaccessible to – because unexperienced by – their male peers. If that backlash comes, it will be from the academic equivalent of those figures who, in 2023 continued to dominate the cultural landscape. These are conservative (even if theoretically radical) people who pride themselves on their superior rational, unsentimental and “common sense” outlook, but whose views tend to have a surprising amount in common with some of the more wayward religious cults. Subscribing to shallowly Darwinist ideas, but only insofar as they reinforce one’s own prejudices and somehow never feeling the need to follow them to their logical conclusions is not new, but it’s very now. Underlying ideas like the ‘survival of the fittest’, which then leads to the more malevolent idea of discouraging the “weak” in society by abolishing any kind of social structure that might support them is classic conservatism in an almost 19th century way, but somehow it’s not surprising to see these views gaining traction in the discourse of the apparently futuristic world of technology. In more that one way, these kinds of traditionalist, rigidly binary political and social philosophies work exactly like religious cults, with their apparently arbitrary cut off points for when it was that progress peaked/halted and civilisation turned bad. That point varies; but to believe things were once good but are now bad must always be problematic, because when, by any objective standards, was everything good, or were even most things good? For a certain class of British politician that point seems to have been World War Two, which kind of requires one to ignore actual World War Two. But the whole of history is infected by this kind of thinking – hence strange, disingenuous debates about how bad/how normal Empite, colonialism or slavery were; incidentially, you don’t even need to read the words of abolitionists or slaves themselves (though both would be good to read) to gain a perspective of whether or not slavery was considered ‘normal’ or bad by the standards of the time. Just look at the lyrics to Britain’s most celebratory, triumphalist song of the 18th century, Rule Britannia. James Thomson didn’t write “Britons never, never, never shall be slaves; though there’s nothing inherently wrong with slavery.” They knew it was something shameful, something to be dreaded, even while celebrating it.

If that backlash comes, it will be from the academic equivalent of those figures who, in 2023 continued to dominate the cultural landscape. These are conservative (even if theoretically radical) people who pride themselves on their superior rational, unsentimental and “common sense” outlook, but whose views tend to have a surprising amount in common with some of the more wayward religious cults. Subscribing to shallowly Darwinist ideas, but only insofar as they reinforce one’s own prejudices and somehow never feeling the need to follow them to their logical conclusions is not new, but it’s very now. Underlying ideas like the ‘survival of the fittest’, which then leads to the more malevolent idea of discouraging the “weak” in society by abolishing any kind of social structure that might support them is classic conservatism in an almost 19th century way, but somehow it’s not surprising to see these views gaining traction in the discourse of the apparently futuristic world of technology. In more that one way, these kinds of traditionalist, rigidly binary political and social philosophies work exactly like religious cults, with their apparently arbitrary cut off points for when it was that progress peaked/halted and civilisation turned bad. That point varies; but to believe things were once good but are now bad must always be problematic, because when, by any objective standards, was everything good, or were even most things good? For a certain class of British politician that point seems to have been World War Two, which kind of requires one to ignore actual World War Two. But the whole of history is infected by this kind of thinking – hence strange, disingenuous debates about how bad/how normal Empite, colonialism or slavery were; incidentially, you don’t even need to read the words of abolitionists or slaves themselves (though both would be good to read) to gain a perspective of whether or not slavery was considered ‘normal’ or bad by the standards of the time. Just look at the lyrics to Britain’s most celebratory, triumphalist song of the 18th century, Rule Britannia. James Thomson didn’t write “Britons never, never, never shall be slaves; though there’s nothing inherently wrong with slavery.” They knew it was something shameful, something to be dreaded, even while celebrating it.

Looking at the scenery, the wildlife and even the roads, you have to wonder; why would anyone not care about this? I don’t mean the Howe of Fife, or Fife, or Scotland, or Britain, or Europe, or the world (although those too); just wherever you happen to be; place. Landscapes should and must change, as we change; not just the geometries and geographies we impose on them, like the furrows and plastic (though it would be nice to do away with the plastic itself), but everything.

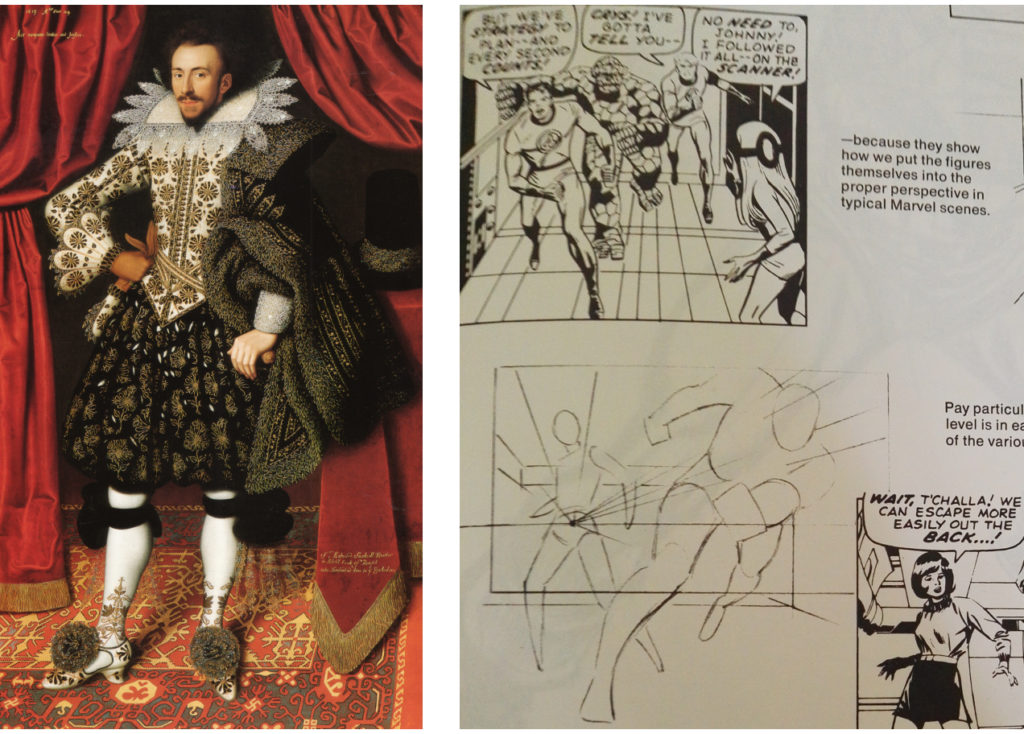

Looking at the scenery, the wildlife and even the roads, you have to wonder; why would anyone not care about this? I don’t mean the Howe of Fife, or Fife, or Scotland, or Britain, or Europe, or the world (although those too); just wherever you happen to be; place. Landscapes should and must change, as we change; not just the geometries and geographies we impose on them, like the furrows and plastic (though it would be nice to do away with the plastic itself), but everything. These back roads are quiet, but although nature is everywhere, it’s deceptive, hardly a natural landscape at all. It has been shaped by generations of human beings, by agriculture and the politics of land ownership. That was just as true in King James’s day, when forests belonged to the King and had their own laws, as it is now.

These back roads are quiet, but although nature is everywhere, it’s deceptive, hardly a natural landscape at all. It has been shaped by generations of human beings, by agriculture and the politics of land ownership. That was just as true in King James’s day, when forests belonged to the King and had their own laws, as it is now.