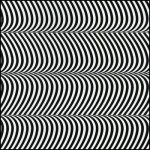

2019 has, in many ways, not been a good year so far. But this summer, the National Galleries of Scotland had (well, has; they are still on) three particularly outstanding exhibitions that brought a bit of light and intelligence to a period of more-than-usual stupidity. At the National Gallery itself, there was the excellent, eye opening and brain-frying Bridget Riley exhibition (closes 22nd September), at the National Portrait Gallery the superb Self Evidence (closes 20th October) in which Francesca Woodman’s tiny, intimate, self-enclosed photographs vibrate balefully in their little corner, overshadowing (for me) the also (but in an entirely different way) intimate and at times frankly challenging monumental works of Robert Mapplethorpe* and, to a lesser extent, the brilliant but (I guess appropriately) don’t-quite-fit-in Diane Arbus portraits of the lives of people marginalised and made invisible by mainstream culture.

*though the Mapplethorpe pictures were the ones that moved me the least, they did provide the priceless spectacle of parents hurrying their curious kids past the notorious 1978 Self Portrait With Whip. They had been warned!

But for me, the highlight of the National Galleries’ summer programme is Cut and Paste: 400 years of Collage at Modern Two (closes 27th October).

Thanks to its inclusive definition of collage (which covers photomontage, traditional collage, plus bits of decoupage, pressed plant samples and even quilting) as well as its historical scope, the exhibition manages to be both focused and wide-ranging, and also (I found) surprisingly moving. What collage does, or at least amplifies – perhaps paradoxically given its use of found/ready-made materials – is that aspect of art that disappears most quickly in reproduction; the hand of the artist. This is art not only as a reflection/projection of culture but one that includes material culture itself.* There is, sometimes regardless of the picture/object, a poignant quality that comes from the materials used, in a way that doesn’t happen with paint, unless you are the kind of conservator who can isolate pigments used to specific periods (I’m not, unfortunately).

*I don’t think this is just pretentious bullshit; but you never know

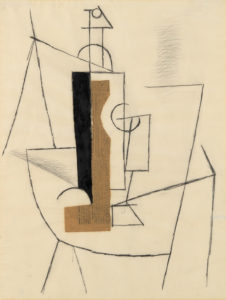

I’m getting ahead of myself here, but a seminal collage that makes an appearance in the exhibition, Pablo Picasso’s Bottle and Glass on a Table (1912) is a classic/typical Picasso cubist/spatial experiment, but the use of newspaper – a very specific, dateable piece of ephemera (from Le Journal, 3 December 1912) – gives the work, instantly and inherently, a dimension largely absent in conventional painting. The feeling that the collage is both artwork and artefact; literally as well as figuratively multi-layered, makes a case for collage as a distinct and special art form, a feeling echoed by the Scottish artist Eduardo Paolozzi (represented by some outstanding works in the exibition), for whom the form offered clarification, where formal art training raised problems and questions: “Unlike the world of school where the universe was systematised in a certain order, the reassembly of this disparate material reflected a true state, both autobiographic and dynamic.” (quoted in the exhibition catalogue, p. 126)

So anyway; the exhibition is arranged chronologically, in the usual Modern Two layout; in various rooms, up the stairs, through the corridors etc, always I think a layout that makes for an engaging, surprising way of looking at art. Partly deliberately (there were too many people in the first room), I went around the exhibition in reverse chronological order and in retrospect that seems like a good decision. This meant that the exhibition opened with the Chapman Brothers’ The Disasters of Everyday Life (2017), a spectacular-looking wall-like object consisting of 80 of Goya’s horrific etchings, The Disasters of War, with of course added bits and pieces, sometimes powerful, sometimes deliberately absurd, I think (though I’d have to go through again the other way) it serves better as a kind of abstract for what is to follow than it would as a conclusion, where peering at a lot of small images might have seemed a bit anticlimactic.

I’m not going to mention every picture in the show, though I can’t think of anything that doesn’t deserve a mention. The first thing to have a major impact for me was Lucy Williams’ 2015 Crescent House, as much a piece of model making as a collage, a strange, small scale (just under a metre long) recreation of a bit of postwar architecture, but simplified and made more colourful, giving it a feeling of harmony almost like a kind of 3D Mondrian.

Crescent House captures something of the intended optimism of the postwar new town planning that’s most often associated now with neglect and urban decay. I don’t know if it’s a generational thing (Williams is around my age), but for me there was something powerfully bittersweet about the feeling of an abandoned, never-quite-attained future, heightened by the realness of the work as an object.

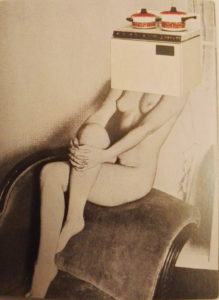

The aesthetic of Crescent House – though that is far lighter in tone – makes me think of the late 70s work of Linder (Sterling), another exhibition highlight. Although similar in its reference points to the pop art collages of Richard Hamilton a couple of decades before (sadly his iconic 1956 collage Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing is not in the exhibition, though they do have a nice work by him, Desk from 1964), the feel of Linder’s work is far darker (it makes me think of the confrontational industrial work of Throbbing Gristle and COUM Transmissions around the same period) and the satire more pointed. Works like her Pretty Girl series(1977) exemplify a particular approach to collage. Using the detritus of everyday life; magazines, posters, advertising, it became a way of embodying in the art a criticism of the culture that it’s a reaction to as well as a product of. It’s a feminist criticism of the objectification of women that uses already depersonalised women (part of the problem) and merges them with actual ‘objects of desire’ from a patriarchal culture that above all else believes in commodification for its own benefit.

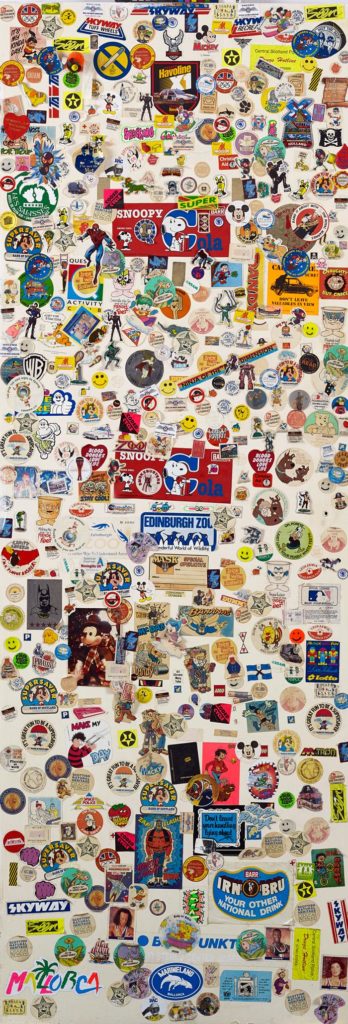

Thanks to the exhibition’s open-minded and inclusive approach, there are some unexpected revelations (but aren’t all revelations unexpected? I mean, that’s obvious). While Craig W. Lowe’s bedroom cupboard door covered in stickers c. 1987-1997) may appeal most as nostalgia, the inclusion of Jamie Reid‘s original Sex Pistols Never Mind The Bollocks cover collage (1977; copyrighted image so I’d better not share) opens realms of not-previously-considered information (at least to me) about one’s record collection. Firstly, the collage is black and white, and secondly, it isn’t just a picture or a ‘file’, it’s an actual thing. Like, presumably all album cover art (and book cover art etc) before the digital age, the NMTB cover in all its yellow and pink (or pink and green) glory, taken for granted forever, is not a picture, it’s a photograph of a picture. In its final form it’s been overlaid with colours, but that object there on the wall in Edinburgh is the thing itself. A strange feeling, like looking at the inscription on a ten pound note and considering that it is a representation of something, rather than ten actual pounds.

The Sex Pistols cover primes the viewer (at least the viewer going through the exhibition backwards) for the various bits of Peter Blake’s Sgt Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band cover that are on show – and, great though they are (and I like Sgt Pepper quite a bit more than I like Never Mind The Bollocks), without that priming, the Beatles items wouldn’t have the same impact; perhaps because the cover itself is clearly a photograph of objects and cut-outs and seeing them is very cool but not really revelatory, the whole is too familiar and iconic to give the frisson of a moment captured. In fact, Blake’s superb, possibly slightly twee The Toy Shop (1962) is a far more vivid time capsule; clearly pointing to Sgt Pepper, its a conglomeration of bits and bobs familiar to children of the 60s – but also to children of later generations as belonging to the same family as the bits & bobs of their own youth (in my case, comics, football stickers, sweets, TV tie-in toys (He-Man et al), but also the odd antiquated throwbacks that still existed, like bows and arrows and balsa wood or polystyrene gliders which came with a weighted plastic propeller so they flew when thrown – do they still make those?). It’s hard to imagine that there will be a generation that can’t relate to The Toy Shop at all, however virtual entertainment becomes, kids will always like stickers.

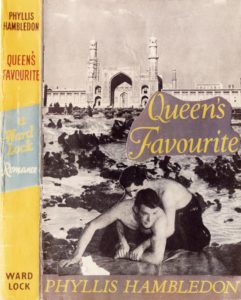

But Blake’s pop art nostalgia – powerful though that is – is one of the few purely positive and joyous post-war works in the show. More typical are the mischievous collage book covers made by Joe Orton and his partner and eventual murderer Kenneth Halliwell. These were put on library books and returned to the library – an act that eventually cost them a six month prison sentence – and they exemplify the sense of the significant, perhaps subversive and illogical accident that drew the surrealists to collage a few generations earlier.

For the surrealists, collage was almost a manifestation of the galvanising quotation from Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror (1869) where a boy could be described as being “as beautiful as a chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella.” This aspect of surrealism is brilliantly captured in Max Ernst’s gothic ‘collage novels’ (one of the most exciting inclusions in the show is an unpublished picture from his 1934 collage novel Une semaine de bonté) as well as in beautiful works by Toyen and some of the collaborative exquisite corpse collages made by André Breton, Jacqueline Lamba and Yves Tanguy, where each artist could only see their own part of the work until it was complete. Again, what I hadn’t really anticipated was the difference it makes seeing these items in real life – for example, I had seen and liked (and own a postcard of) Roland Penrose’s untitled 1937 postcard collage, but seeing it, life size, and looking at the actual real postcards stuck to it, was a weirdly moving experience. But why? It’s something about the immediacy and associations of familiar things, the thought perhaps of Roland Penrose actually going into a newsagent and buying the postcards one day in 1937. Why that should be more moving than an artist using paint I don’t know, except that, like the scrapbooks owned by Tristan Tzara (very exciting to see) and the paper cutouts by Matisse (which until now I’ve never been a fan of) it brings the whole process of making art into an immediate, almost tangible one.

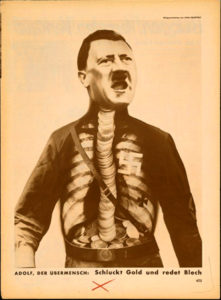

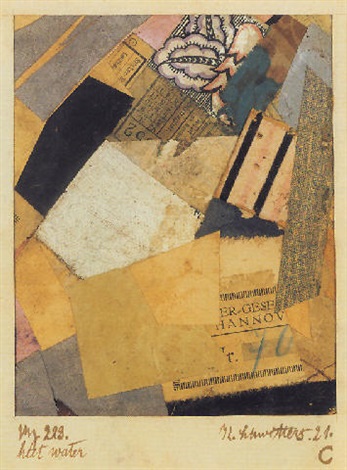

The work of the Dadaists (Hannah Höch was the main reason I wanted to see the show) is less self-consciously unconscious (well, that makes no sense) than the surrealist works, but the element of satire and sometimes bitter humour – especially in John Heartfield’s iconic anti-Nazi photomontages – make them the spiritual ancestors of the works of artists like Carolee Schneemann and Nancy Spero in the 1960s as well as Linder and even Terry Gilliam in the 70s. Highlights for me were the selection of works by Kurt Schwitters, whose own version of Dada, Merz, even had a collage-like genesis, the word itself apparently derived from a fragment of text relating to a banking firm (Kommerz und Privatbank). The fact that the word Merz also has echoes in the words schwerz (pain) and ausmerzen (to weed out or discard) adds to the sense that this was a movement (if you can call one person a movement) for which collage wasn’t an entertaining diversion, but a central idea. The cumulation of meanings and associations in works like Merz 229: Heet Water (1921) makes these small works with their train tickets, textiles, playing cards – pretty much anything that could be cut up and stuck down – powerfully evocative, as well as decorative in themselves.

The section on the birth of modernist collage features a group of Picasso works including the the aforementioned Bottle and Glass on a Table, which form year zero of modernist collage, alongside works by peers including Braque (who may actually be the first modernist collage-maker) and Juan Gris (whose The Sunblind, 1914 is a highlight) and then the ripples spreading outwards from that explosive group of works, including the Russian constructivists and suprematists, the Italian Futurists and even the Bloomsbury group in the UK; I was very impressed to come across a painting by Vanessa Bell (Portrait of Molly MacCarthy, 1914-5) that didn’t immediately wilt into insignificance when surrounded by the big names of European modernism.

It seems obvious to say that collage is comparatively egalitarian insofar as you don’t need to be able to draw or paint to do it – and it’s true that works by generally non-visual artists like Breton and Joe Orton have a similar energy and atmosphere as those by more conventional artists, but it’s also noticeable that, pre-modernism, although the idea of collage existed and there was sometimes that same element of playfulness, the work is more notable for its skill and ingenuity – especially in the Victorian photomontages – than for any disruptive or ironic qualities. But collage being what it is, it’s here that the sense mentioned earlier of the collage as actual material culture comes into play again, sometimes – especially for me in the small character pieces by George Smart from the early 19th century – powerfully so. Somehow, these little watercolour paintings adorned with carefully cut out and arranged pieces of paper and fabric (irresistibly reminiscent to me of the ‘fuzzy felt’ sets I played with as a child) bring us closer to the artist than just paint on canvas would do.

This is perhaps art history as human interest and association rather than as aesthetics (this is especially true in the case of the Victorian scraps and scrapbooks, perhaps because the ready-made nature of the scraps themselves makes the objects feel less like the works of an artist and more like a hobby; nothing wrong with that, but as the sort of things you see in auctions and junk shops they have the aura of being ephemera, rather than using ephemera to make something else; a false distinction perhaps), but for me this exhibition brings those two aspects of art – the human/historical and the aesthetic/technical together in a deep and very satisfying way.

This is perhaps art history as human interest and association rather than as aesthetics (this is especially true in the case of the Victorian scraps and scrapbooks, perhaps because the ready-made nature of the scraps themselves makes the objects feel less like the works of an artist and more like a hobby; nothing wrong with that, but as the sort of things you see in auctions and junk shops they have the aura of being ephemera, rather than using ephemera to make something else; a false distinction perhaps), but for me this exhibition brings those two aspects of art – the human/historical and the aesthetic/technical together in a deep and very satisfying way.

I have no real criticisms of the exhibition; it is thought provoking, beautiful to look at and put together with care and imagination. It might have been nice to have had something by some of the other artists most strongly associated with collage, like Romare Bearden and Wangechi Mutu; but if an exhibition leaves you wanting more that can’t be a bad thing.

***POSTSCRIPT***

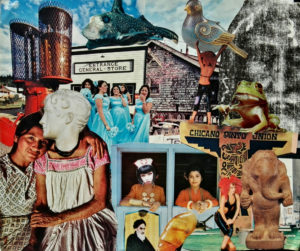

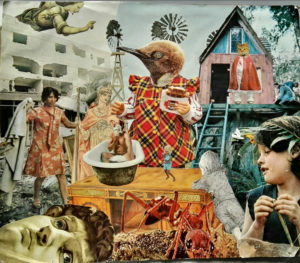

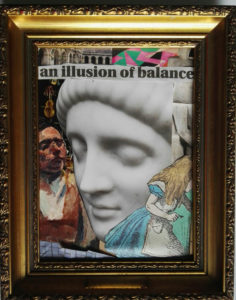

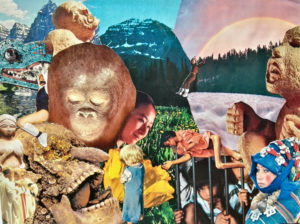

Since I mentioned the anyone-can-do-it aspect of collage, I might as well mention that I went through a phase, especially in my student days of making collages, and while they are nothing special, they do have a kind of diary-esque subtext which has only really become apparent over time. Since it’s my website and no-one can stop me, here are a couple of examples, plus a more recent one.

Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so.

Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so. Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears.

Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears. every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation

every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation  isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism.

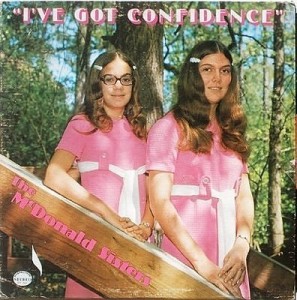

isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism. Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all.

Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all. This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.

This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.