This article (like several others) came out of a conversation with my friend Paul, and he writes better than I do about 80s horror (and many other things) at Into the Gyre

The 1980s was, famously, the decade when pop culture became corporate, encapsulated in the omnipresent corporate or corporate-style logo. Obviously both corporations and logos long pre-dated the 80s, but it was in that era that it became an all-encompassing ideal. In the 1960s, the first really modern teenagers* had written the names of their favourite bands on their school books or bags and twenty years later their children were doing much the same thing, only they were painstakingly copying logos from album sleeves or tape inlay cards.

*you could say the 50s teenagers were the first, but they were pioneers; the 60s generation was the first to grow up with the expectation of being teenagers, with all that entailed in terms of pop music and rebellious teenage behaviour

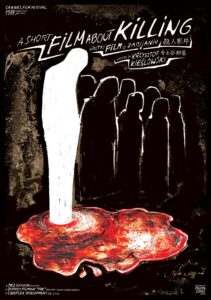

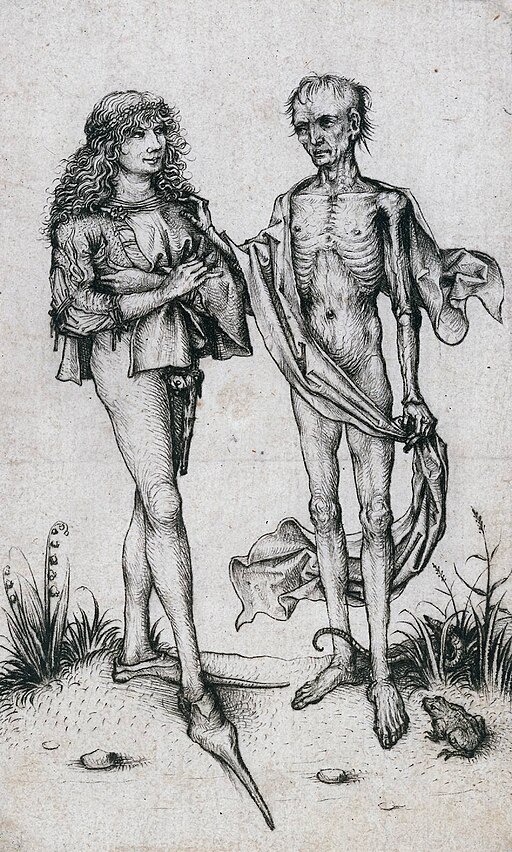

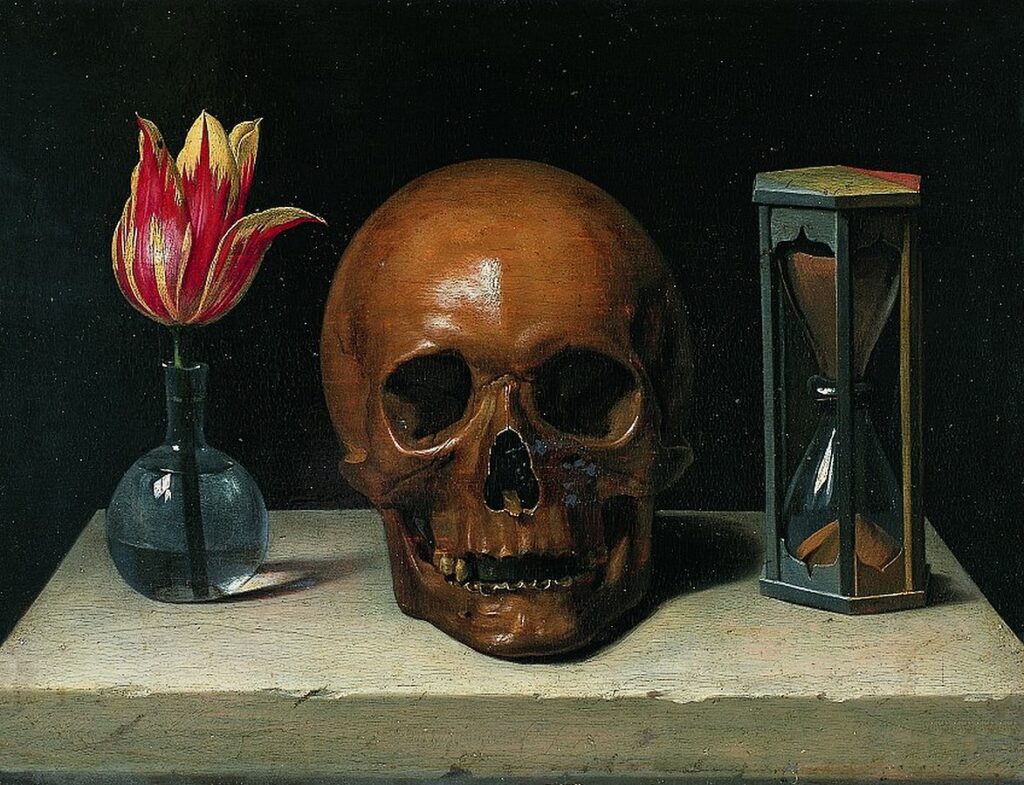

As a young horror fan in the mid-to-late 1980s, one of the things that made the notorious video nasties of the previous generation seem so alluringly grimy and disreputable was their lack of slickness. 1980s horror franchises – in themselves a symptom of the decade of accelerated capitalism – even ones with their roots in the 70s independent cinema boom like Halloween – had logos, they had mascots like Freddy and Jason and Pinhead, they had rock songs on the soundtrack – they were corporate and, to young teenagers at least, they were cool. There was no way to make a grotty, un-theatrical, special effects-free film like I Spit on Your Grave seem cool. There was an attempt to make a franchise out of the Texas Chain Saw Massacre, but Leatherface wasn’t iconic in quite the way that Jason was, let alone an almost cartoon character like Freddy Krueger. Murderous, inbred yokels in rural Texas might well be scary but they weren’t easily assimilated into glossy hair metal videos.

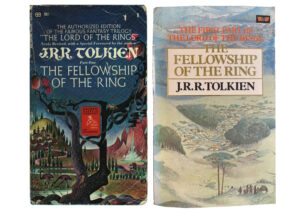

The publishing world was no different. In the fantasy realm, the hippyish typefaces and sometimes grotesque psychedelic imagery of the great 60s and 70s paperbacks were replaced with foil letters in block type and tastefully elevated landscapes. Tasteful is of course a relative term and within a decade, that utterly 80s look – a publishing counterpart to magnolia painted walls and a beige Laura Ashley aesthetic which married an almost clinical sense of restraint, as if embarrassed by the childishness of elves, wizards and dragons, but combined it with bold, business card-style, metallic sans-serif lettering – would seem just as trashy in its way as the more florid 70s fashions had at the time.

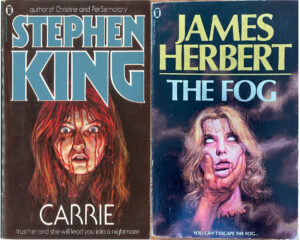

But, unlike fantasy fiction, where the biggest name in the 80s remained the late J.R.R. Tolkien, the horror genre had star writers who transcended the genre and became part of the pop cultural zeitgeist, Most of the current ‘big names’ in 80s fantasy, like Terry Brooks and Stephen R Donaldson, were writers whose key works belonged firmly to the post-Tolkien 1970s and never escaped a (very big) fantasy audience. Horror was different. Like the fantasy genre, its biggest names – Stephen King (everywhere) and James Herbert (especially in the UK, though his books sold millions worldwide) – had had their first successes in the first half of the 1970s, but as the 70s evolved into the 80s, both their work itself and the way it was packaged began to align with the spirit of the age. The fanbase for horror broadened until the big horror novels became the big airport novels and big supermarket novels and the basis for successful Hollywood movies. The books became bigger and more cinematic (but I talked about that here so won’t again) and their design more stylish, until they resembled the movie posters of the time; but with one major difference. There were of course iconic directors in the 80s, but even the biggest of them – Steven Spielberg, say, or Martin Scorcese – naturally didn’t dominate the posters for their films the way that Stephen King or James Herbert did on their books. In that respect, the authors were more like the star actors of the day, but where Stallone or Arnold Schwarzenegger were only one element, albeit a dominant one, in their star vehicles, with the books you knew that whatever you got would the real, unadulterated thing, unless you happened to be a fan of Virginia (“VC”) Andrews, but she was a special case back then.

The extent to which the star authors, rather than the books themselves, were the selling point, can be seen in their evolving covers. After a decade of disparate designs and variable artwork, often not especially horror-centric, publishers like New English Library, Futura and Star began treating books by horror authors as franchises, each with their own logo and aesthetic. Stephen King and James Herbert, to stick with the big two, demonstrate contrasting, but very 80s horror alternatives. James Herbert – who, with a background in advertising and art direction, took a direct interest in how his novels were packaged – went with the 80s version of classy as epitomised by mid-priced boxes of chocolates; a restrained palette dominated by either black or white, with lettering in gold or silver foil. They were eye-catching, moody and, to a teenager, adult looking.

Stephen King’s UK publishers (including Herbert’s publisher N.E.L. – but frustratingly, including several others; keeping one truly consistent image annoyingly out of reach) clearly realised that the selling point – the brand, in the parlance of the times etc – was King himself. To that end, the actual cover illustrations and even the prominence of the titles of the books took up less and less space, while the author’s name was treated to something like the logo of a metal band, and was big enough to be spotted across a crowded newsagent or bookshop. Sometimes the author’s name was in foil, sometimes it was embossed, but for at least a few years the covers of his main series of novels – as with James Herbert’s – had the uniformity of a corporate identity.

Where the genre’s biggest stars and their publishers led, others followed; all of the big names of 80s horror tended to follow either the King or the Herbert approach; after wildly variable and sometimes lamentable 70s editions, Ramsey Campbell’s books took on the sleek, Herbertian image. American blockbuster authors like Dean R Koontznd Peter Straub’s books tended to follow the King blueprint.

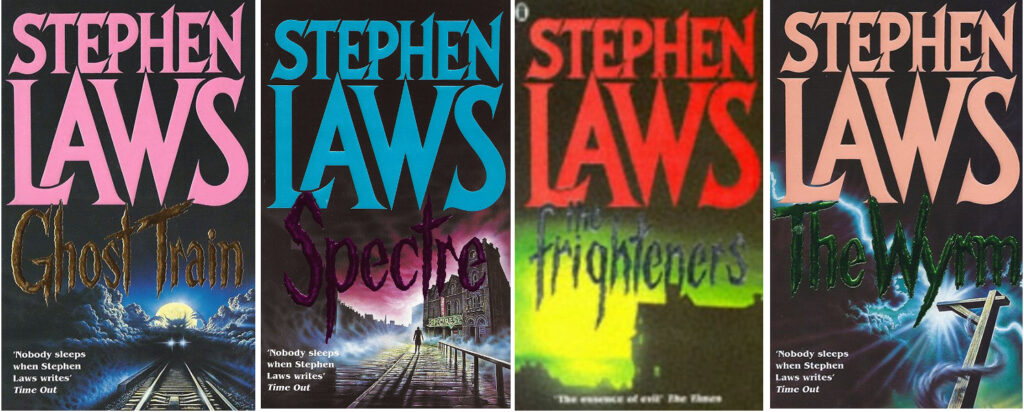

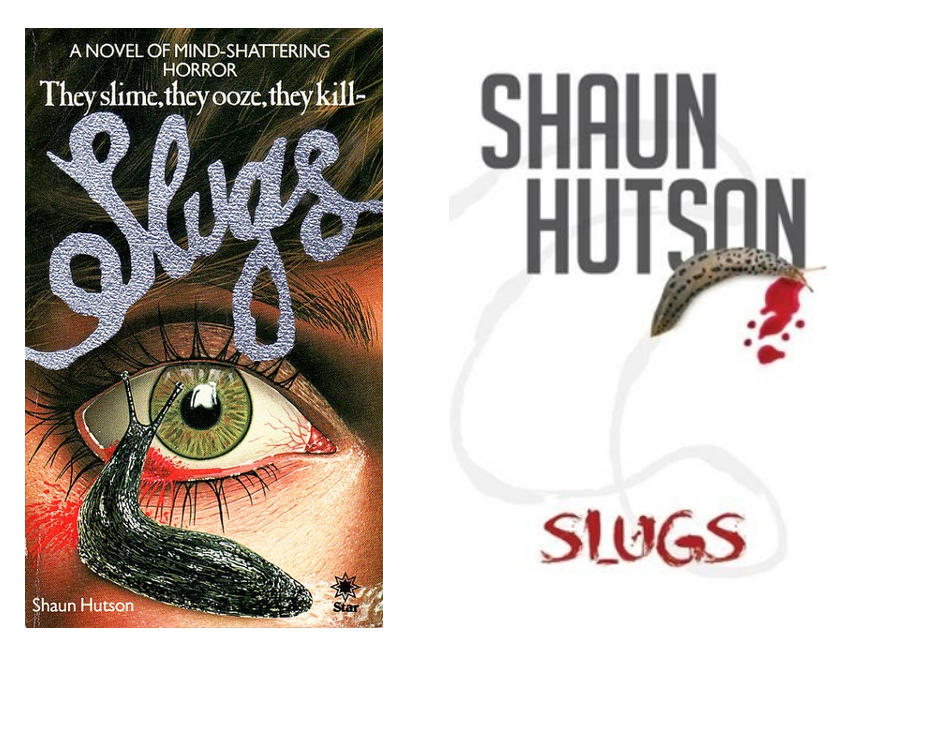

Gore authors had a kind of niche of their own. The early books of the UK’s most notorious horror author of the era, Shaun Hutson, played down the author’s name in favour of a gaudy movie poster look with the titles in a distinctive ‘slug trail’ font – and his US counterpart Richard Laymon’s works were very similarly packaged (the covers above both look like they could be the work of Danny Flynn, mentioned here, though I haven’t checked). As the sales of both authors increased during the boom years of the 80s, their packaging became – like their work – relatively more sophisticated. In the UK, Sphere mimicked the classy Herbert look for Hutson’s later 80s novels like Assassin and Victims, with the author’s name (embossed, in foil) becoming more of a focal point, while Laymon’s name became almost as logo-like as Stephen King’s. Laymon was far from alone in this. The brand-like identity of Stephen King, and the sheer volume of his sales, meant that the classic ‘logo’ look of his books was highly influential, to put it mildly. The range of King-influenced cover art ranges from the definitely ‘post-King’ 80s covers of authors like John Farris and Rex Miller, to the frankly imitative NEL covers for Stephen Laws, whose 80s books bring to mind the theoretical “Moron in a hurry” cited in court in cases of trademark infringement; not that said moron would have a bad time if they accidentally bought a Stephen Laws novel – but they would know they weren’t reading Stephen King.

In almost all respects, Clive Barker was the outsider in the world of 80s horror – most definitely of it, but not defined by it. His debut novel The Damnation Game was initially packaged as typical mid-80s horror stodge but graduated, as his reputation grew, to Stephen King style packaging, even as Sphere Books simultaneously took the bold step of publishing his Books of Blood short story collections with Barker’s own fantastical (and in come cases gory) paintings on the covers, immediately putting the author in a dangerous-looking category of his own. Clive Barker’s books looked both more graphic and more outlandish than the usual blockbuster horror authors. From then until the end of the horror boom his work coexisted in the two camps of mainstream and (for want of a better world) alternative horror. The packaging of the 1989 first edition of his short novel Cabal (filmed as Nightbreed) is pure, commercial 80s design; it looks more like a movie poster than the actual Nightbreed movie poster and is complete with logo-like title and gold foil for the author’s name. But around the same time, his dark fantasy masterpiece Weaveworld featured a more imaginative, sophisticated style, taking its lead from the Books of Blood. Weaveworld had a more formal design sense that was flexible enough to be applied to the rest of Barker’s oeuvre, so that when the horror bubble burst and everything 80s suddenly looked as cringingly tacky and dated as mullets and shoulder pads, Barker’s brand alone among his horror peers easily made the transition into the new decade.

From 1990 until at least until the turn of the millennium, Stephen King’s publishers experimented with everything from tasteful minimalism to gaudy dayglo colours, the only constant being the prominence of the author’s name on the covers. That sense of immediate brand recognition dissolved around the time of The Dark Half has never been quite as strong since, and an 80s Stephen King collection still has a satisfyingly coherent look that isn’t matched by later editions. James Herbert mostly stuck with the ‘classy’ look of his late 80s books but with a sense of diminishing returns as the titles and cover images became less confrontational and the whole look less fashionable. In the 90s, much of what had been packaged as full-blooded horror tended to be given more of a fashionable ‘urban thriller’ look, just as in cinema, the Freddy and Jason franchises limped to an ignoble (if temporary) end, Hannibal Lecter emerged as a supposedly less cheesy horror villain and nobody wanted hair metal on their soundtracks anymore. It was a new age.

I loved Nechochwen’s

I loved Nechochwen’s  Ghost World have made some of my favourite albums; I was immediately smitten with their 2017 debut album, which was my

Ghost World have made some of my favourite albums; I was immediately smitten with their 2017 debut album, which was my  Hmm. I gave this a go because, despite the fact that industrial metal is one of my least favourite genres of music in the world, Swiss black metal has a special place in my heart and LADLO is a very dependable label. And..? Well, not exactly my cup of tea, but it’s good, there’s a nice chaotic, noisy atmosphere and it reminded me at times of Abigor (who I do like) and Blacklodge (who I occasionally like). The atmospheres and the choral bits are really cool and the noisy stuff with sirens etc is impressively alarming, though not nice if you have a headache.

Hmm. I gave this a go because, despite the fact that industrial metal is one of my least favourite genres of music in the world, Swiss black metal has a special place in my heart and LADLO is a very dependable label. And..? Well, not exactly my cup of tea, but it’s good, there’s a nice chaotic, noisy atmosphere and it reminded me at times of Abigor (who I do like) and Blacklodge (who I occasionally like). The atmospheres and the choral bits are really cool and the noisy stuff with sirens etc is impressively alarming, though not nice if you have a headache.

I

I

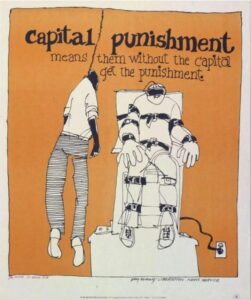

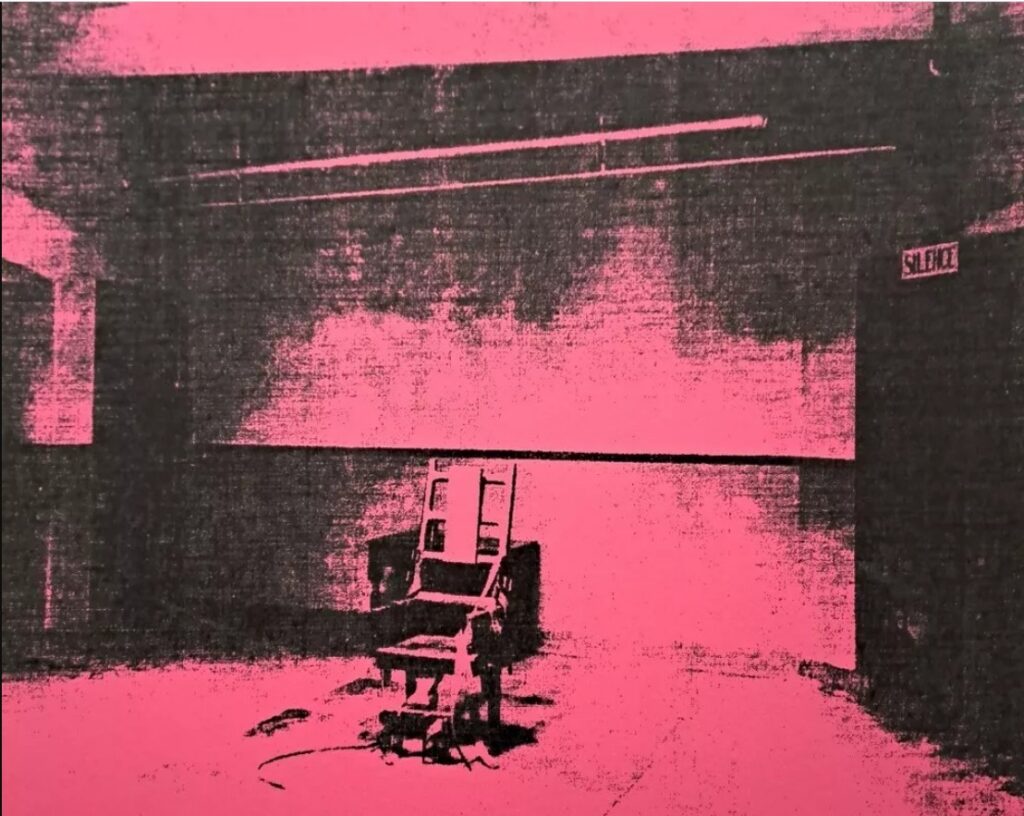

The current case of Luigi Mangione is far stranger. It’s the only time I can recall that the supporters (in this case I think ‘fans’ would be just as correct a word) of someone accused of murder want the suspect to be guilty rather than innocent. Whether they would still feel that way if he looked different or had a history of violent crime or had a different kind of political agenda is endlessly debatable, but irrelevant. It looks as if the State will be seeking the death penalty for him and for all the reasons listed above I think that’s wrong. But assuming that he’s guilty, which obviously one shouldn’t do (and if he isn’t, Jesus Christ, good luck getting a fair trial!) Mangione himself and some of his fans, should really be okay with it. If he is guilty, he hasn’t done anything to help a single person to get access to healthcare or improve the healthcare system or even effectively protested against it in a way that people with political power can positively react to. UnitedHealthcare still has a CEO, still has dubious political connections and still treats people very badly. That doesn’t mean that it’s an unassailable monolith that can never be changed, but clearly removing one figurehead isn’t how it can be done.

The current case of Luigi Mangione is far stranger. It’s the only time I can recall that the supporters (in this case I think ‘fans’ would be just as correct a word) of someone accused of murder want the suspect to be guilty rather than innocent. Whether they would still feel that way if he looked different or had a history of violent crime or had a different kind of political agenda is endlessly debatable, but irrelevant. It looks as if the State will be seeking the death penalty for him and for all the reasons listed above I think that’s wrong. But assuming that he’s guilty, which obviously one shouldn’t do (and if he isn’t, Jesus Christ, good luck getting a fair trial!) Mangione himself and some of his fans, should really be okay with it. If he is guilty, he hasn’t done anything to help a single person to get access to healthcare or improve the healthcare system or even effectively protested against it in a way that people with political power can positively react to. UnitedHealthcare still has a CEO, still has dubious political connections and still treats people very badly. That doesn’t mean that it’s an unassailable monolith that can never be changed, but clearly removing one figurehead isn’t how it can be done.

Henrik Palm – Nerd Icon (Svart Records) – sort of 80s-ish, sort of metal-ish, 100% individual

Henrik Palm – Nerd Icon (Svart Records) – sort of 80s-ish, sort of metal-ish, 100% individual Myriam Gendron – Mayday (Feeding Tube) – I loved Not So Deep as a Well ten years ago (mentioned in passing

Myriam Gendron – Mayday (Feeding Tube) – I loved Not So Deep as a Well ten years ago (mentioned in passing  Ihsahn – Ihsahn (Candlelight) – wrote about it

Ihsahn – Ihsahn (Candlelight) – wrote about it  One of my top 3 or 4 albums of all time, John Cale’s Paris 1919 was reissued this year, his latest POPtical Illusion was good too

One of my top 3 or 4 albums of all time, John Cale’s Paris 1919 was reissued this year, his latest POPtical Illusion was good too Mick Harvey – Five Ways to Say Goodbye (Mute) – lovely autumnal album by ex-Bad Seed and musical genius, more

Mick Harvey – Five Ways to Say Goodbye (Mute) – lovely autumnal album by ex-Bad Seed and musical genius, more

Aara –

Aara –  Claire Rousay –

Claire Rousay –  Alcest – Chants de L’Aurore (Nuclear Blast) – seems so long ago that I almost forgot about it, but this was (I thought) the best Alcest album for years, beautiful, wistful and generally lovely. I talked to Neige about it at the time, I should post that interview here at some point!

Alcest – Chants de L’Aurore (Nuclear Blast) – seems so long ago that I almost forgot about it, but this was (I thought) the best Alcest album for years, beautiful, wistful and generally lovely. I talked to Neige about it at the time, I should post that interview here at some point!

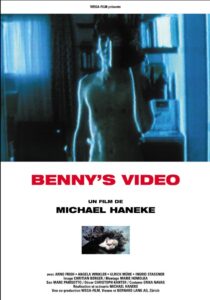

2023 was the usual mixed bag of things; I didn’t see any of the big movies of

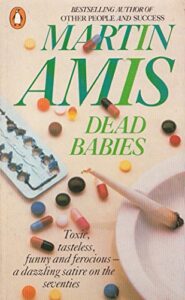

2023 was the usual mixed bag of things; I didn’t see any of the big movies of the year yet. I have watched half of Saltburn, which so far makes me think of the early books of Martin Amis, especially Dead Babies (1975) and Success (1978) – partly because I read them again after he died last year. They are both still good/nasty/funny, especially Success, but whereas I find that having no likeable characters in a book is one thing, and doesn’t stop the book from being entertaining, watching unlikeable characters in a film is different – more like spending time with actual unlikeable people, perhaps because – especially in a film like Saltburn – you can only guess at their motivations and inner life. So, the second half of Saltburn remains unwatched – but I liked it enough that I will watch it.

the year yet. I have watched half of Saltburn, which so far makes me think of the early books of Martin Amis, especially Dead Babies (1975) and Success (1978) – partly because I read them again after he died last year. They are both still good/nasty/funny, especially Success, but whereas I find that having no likeable characters in a book is one thing, and doesn’t stop the book from being entertaining, watching unlikeable characters in a film is different – more like spending time with actual unlikeable people, perhaps because – especially in a film like Saltburn – you can only guess at their motivations and inner life. So, the second half of Saltburn remains unwatched – but I liked it enough that I will watch it.

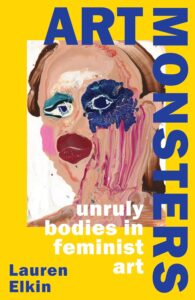

I read lots of good books in 2023 – I started keeping a list but forgot about it at some point – but the two that stand out in my memory as my favourites are both non-fiction. Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art is completely engrossing and full of exciting ways of really looking at pictures. I wrote at length about Elena Kostyuchenko’s I Love Russia

I read lots of good books in 2023 – I started keeping a list but forgot about it at some point – but the two that stand out in my memory as my favourites are both non-fiction. Lauren Elkin’s Art Monsters: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art is completely engrossing and full of exciting ways of really looking at pictures. I wrote at length about Elena Kostyuchenko’s I Love Russia  It’s no great surprise to me that my favourite books of the year would be – like much of my favourite art – by women. Though I think the individual voice is crucial in all of the arts, individuals don’t grow in a vacuum and because female (and, more widely, non-male) voices and viewpoints have always been overlooked, excluded, marginalised and/or patronised, women and those outside of the standard, traditional male authority figures more generally, tend to have more interesting and insightful perspectives than the ‘industry standard’ artist or commentator does. The first time that thought really struck me was when I was a student, reading about Berlin Dada and finding that Hannah Höch was obviously a much more interesting and articulate artist than (though I love his work too) her partner Raoul Hausmann, but that Hausmann had always occupied a position of authority and a reputation as an innovator, where she had little-to-none. And the more you look the more you see examples of the same thing. In fact, because women occupied – and in many ways still occupy – more culturally precarious positions than men, that position informs their work – thinking for example of artists like Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage or – a bigger name now – Frida Kahlo – giving it layers of meaning inaccessible to – because unexperienced by – their male peers.

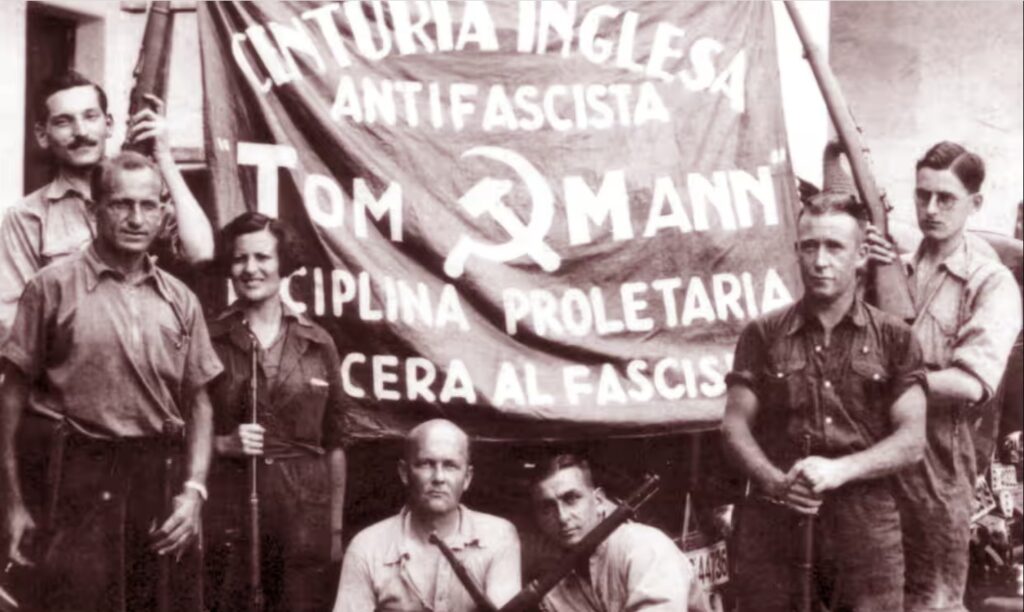

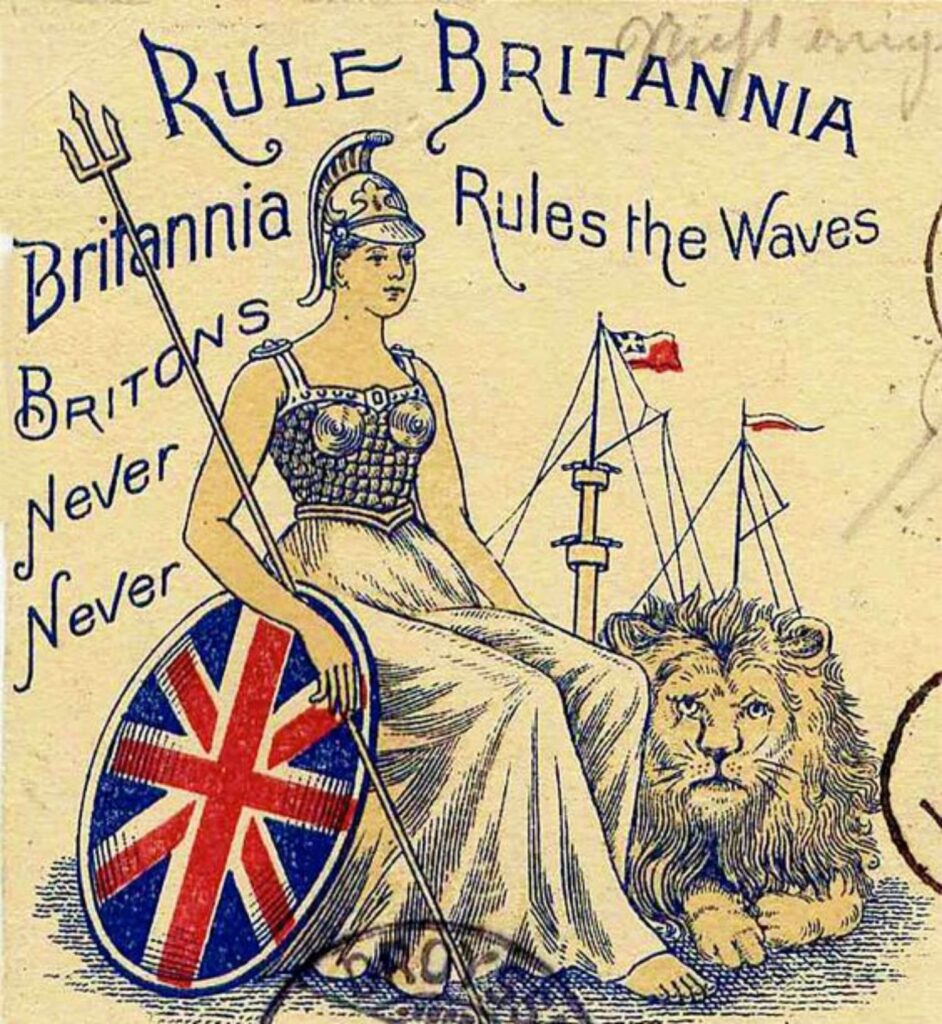

It’s no great surprise to me that my favourite books of the year would be – like much of my favourite art – by women. Though I think the individual voice is crucial in all of the arts, individuals don’t grow in a vacuum and because female (and, more widely, non-male) voices and viewpoints have always been overlooked, excluded, marginalised and/or patronised, women and those outside of the standard, traditional male authority figures more generally, tend to have more interesting and insightful perspectives than the ‘industry standard’ artist or commentator does. The first time that thought really struck me was when I was a student, reading about Berlin Dada and finding that Hannah Höch was obviously a much more interesting and articulate artist than (though I love his work too) her partner Raoul Hausmann, but that Hausmann had always occupied a position of authority and a reputation as an innovator, where she had little-to-none. And the more you look the more you see examples of the same thing. In fact, because women occupied – and in many ways still occupy – more culturally precarious positions than men, that position informs their work – thinking for example of artists like Leonora Carrington, Kay Sage or – a bigger name now – Frida Kahlo – giving it layers of meaning inaccessible to – because unexperienced by – their male peers. If that backlash comes, it will be from the academic equivalent of those figures who, in 2023 continued to dominate the cultural landscape. These are conservative (even if theoretically radical) people who pride themselves on their superior rational, unsentimental and “common sense” outlook, but whose views tend to have a surprising amount in common with some of the more wayward religious cults. Subscribing to shallowly Darwinist ideas, but only insofar as they reinforce one’s own prejudices and somehow never feeling the need to follow them to their logical conclusions is not new, but it’s very now. Underlying ideas like the ‘survival of the fittest’, which then leads to the more malevolent idea of discouraging the “weak” in society by abolishing any kind of social structure that might support them is classic conservatism in an almost 19th century way, but somehow it’s not surprising to see these views gaining traction in the discourse of the apparently futuristic world of technology. In more that one way, these kinds of traditionalist, rigidly binary political and social philosophies work exactly like religious cults, with their apparently arbitrary cut off points for when it was that progress peaked/halted and civilisation turned bad. That point varies; but to believe things were once good but are now bad must always be problematic, because when, by any objective standards, was everything good, or were even most things good? For a certain class of British politician that point seems to have been World War Two, which kind of requires one to ignore actual World War Two. But the whole of history is infected by this kind of thinking – hence strange, disingenuous debates about how bad/how normal Empite, colonialism or slavery were; incidentially, you don’t even need to read the words of abolitionists or slaves themselves (though both would be good to read) to gain a perspective of whether or not slavery was considered ‘normal’ or bad by the standards of the time. Just look at the lyrics to Britain’s most celebratory, triumphalist song of the 18th century, Rule Britannia. James Thomson didn’t write “Britons never, never, never shall be slaves; though there’s nothing inherently wrong with slavery.” They knew it was something shameful, something to be dreaded, even while celebrating it.

If that backlash comes, it will be from the academic equivalent of those figures who, in 2023 continued to dominate the cultural landscape. These are conservative (even if theoretically radical) people who pride themselves on their superior rational, unsentimental and “common sense” outlook, but whose views tend to have a surprising amount in common with some of the more wayward religious cults. Subscribing to shallowly Darwinist ideas, but only insofar as they reinforce one’s own prejudices and somehow never feeling the need to follow them to their logical conclusions is not new, but it’s very now. Underlying ideas like the ‘survival of the fittest’, which then leads to the more malevolent idea of discouraging the “weak” in society by abolishing any kind of social structure that might support them is classic conservatism in an almost 19th century way, but somehow it’s not surprising to see these views gaining traction in the discourse of the apparently futuristic world of technology. In more that one way, these kinds of traditionalist, rigidly binary political and social philosophies work exactly like religious cults, with their apparently arbitrary cut off points for when it was that progress peaked/halted and civilisation turned bad. That point varies; but to believe things were once good but are now bad must always be problematic, because when, by any objective standards, was everything good, or were even most things good? For a certain class of British politician that point seems to have been World War Two, which kind of requires one to ignore actual World War Two. But the whole of history is infected by this kind of thinking – hence strange, disingenuous debates about how bad/how normal Empite, colonialism or slavery were; incidentially, you don’t even need to read the words of abolitionists or slaves themselves (though both would be good to read) to gain a perspective of whether or not slavery was considered ‘normal’ or bad by the standards of the time. Just look at the lyrics to Britain’s most celebratory, triumphalist song of the 18th century, Rule Britannia. James Thomson didn’t write “Britons never, never, never shall be slaves; though there’s nothing inherently wrong with slavery.” They knew it was something shameful, something to be dreaded, even while celebrating it.

My favourite album of that year was Ihsahn’s Das Seelenbrechen, and it’s still one of my favourite albums. I rarely listen to it all the way through at the moment, but various tracks, such as Pulse, Regen and NaCL are still in regular rotation

My favourite album of that year was Ihsahn’s Das Seelenbrechen, and it’s still one of my favourite albums. I rarely listen to it all the way through at the moment, but various tracks, such as Pulse, Regen and NaCL are still in regular rotation My favourite album of 2014 was

My favourite album of 2014 was My album of 2015 was Life is a Struggle, Give Up by

My album of 2015 was Life is a Struggle, Give Up by

I wouldn’t necessarily say I was aware of it at the time, but 2016 was a great year for music. My album of the year was Wyatt at the Coyote Palace by Kristin Hersh (which I enthused about

I wouldn’t necessarily say I was aware of it at the time, but 2016 was a great year for music. My album of the year was Wyatt at the Coyote Palace by Kristin Hersh (which I enthused about

2017 had fewer standouts for me but my album of the year, the self-titled debut by Finnish alt-rock band Ghost World, which I wrote enthusiastically about

2017 had fewer standouts for me but my album of the year, the self-titled debut by Finnish alt-rock band Ghost World, which I wrote enthusiastically about  I was hugely surprised in 2018 to find that my album of the year was an electronic one,

I was hugely surprised in 2018 to find that my album of the year was an electronic one,  In 2019, I loved another Collectress album, Different Geographies but it didn’t replace or match Mondegreen in my affections. I can’t seem to find my album of the year strangely, but it might well have been Youth in Ribbons by Revenant Marquis, still my favourite of that prolific artist’s releases.

In 2019, I loved another Collectress album, Different Geographies but it didn’t replace or match Mondegreen in my affections. I can’t seem to find my album of the year strangely, but it might well have been Youth in Ribbons by Revenant Marquis, still my favourite of that prolific artist’s releases.