Brave New World, Nineteen Eighty-Four, the Handmaid’s Tale and V for Vendetta are among the most uncomfortably prescient works of dystopian fiction, but I think the one that most precisely captures the tenor and atmosphere of the present time is more modest: a humorous two-part comic strip story from 1980, written by V creator, novelist and (ex-)comics legend Alan Moore (Watchmen, V for Vendetta, From Hell etc) and drawn by the great Steve Dillon. While Karl Marx may not have been wrong in his often-quoted observation* that history repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce, Alan Moore recognised, like Camus before him, that whatever history is, and whatever the future may be, the present tends to exist in a pretty much perpetual state of tragi-farce.

*The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, 1852

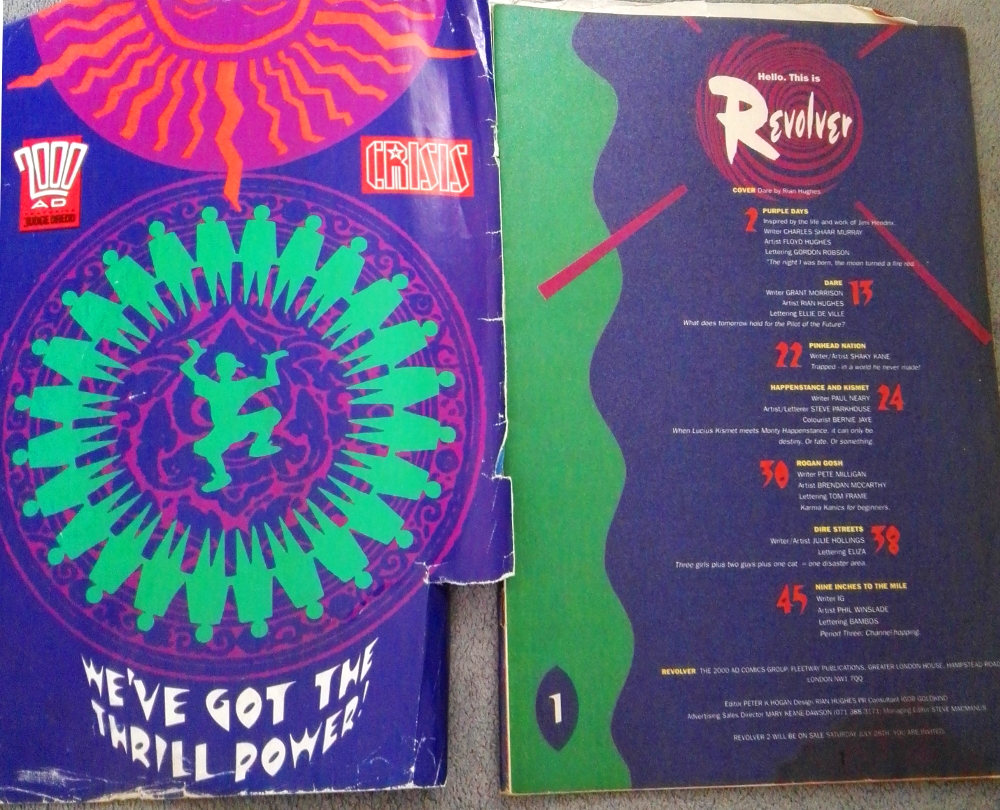

The Moore/Dillon story came with the ominous title Final Solution and appeared in one of 2000AD comic’s regular features, a more or less standalone, twist-ending, Twilight Zone/Tales of the Unexpected-like series called Future Shocks. In Final Solution, Moore and Dillon depict a crime-riddled future (not unlike that in 2000AD’s most famous strip, Judge Dredd) in which the ‘world’s smartest man,’ Abelard Snazz, President of the “Think Inc” corporation envisions, with the aid of a ‘think drink,’ a technological remedy for society’s ills. Obviously, the idea of a genius tech billionaire with a silly name who takes drugs in order to fuel his genius is far-fetched, but the story unfolds in a way that seemed far sillier when I read it as a child than it does now.

Snazz decides (pre-empting the Robocop franchise’s comedy-villain ED-209) that the answer to the crime problem is super-efficient police robots. And so it proves. The only problem is that the robots are too efficient and although the immediate crime problem is solved, there’s no way to turn the robots off and so they become ever more draconian in their crime-stopping. Ultimately they themselves begin to have a negative impact on society and in a particularly memorable and silly panel, a news anchor is arrested live on air for breaking the ‘laws of good taste’ with his clothing choice.

Snazz is again approached to come up with ideas and this time his solution is robot criminals to keep the robot police busy. Predictably it again works too well and so many humans are injured in the resulting crossfire that he comes up with ‘innocent bystander’ robots to take their place. In the end, the earth is overrun with robots fighting each other and humanity has to leave for another planet. On the journey out, Snazz has a vision of a new robot planet and in the last panel he and his sycophantic robot butler Edwin are thrown out of the spacecraft and Snazz has one final vision; “I see… empty air cylinders! I see… oxygen starvation! I see… a slow and painful death! What do you think, Edwin?” and the punchline; “You’re a genius, master!” It’s funny.

Cautionary tales – any tales really – being products of the time they are imagined in, Alan Moore wrote about robots, which in 1980 were one of the most obvious projections of an expected future. Unusually, but both ironically and logically, Hollywood was more on the money* in its choice of future villains: “The Company” (the Weyland Corporation, or for proper nerds, the Weyland-Yutani Corporation), the Tyrell Corporation, Cyberdyne Systems, Omni Consumer Products, Rekall. These are very different institutions from Huxley’s envisioned ‘World State’ or Orwell’s ‘The Party’ or Atwood’s ‘Gilead’ or Yevgeny Zamyatin’s ‘The One State.’ In the first half of the 20th century the most repressive and authoritarian regimes, fascist and communist alike, seemed like the plausible future; and both made corporations subordinate to the state and in fact absorbed them into the state. What the writers of early 20th century dystopias couldn’t have foreseen is that as consumer culture accelerated it became far more attractive for states (even to a surprising extent quasi-communist ones like China) to make themselves attractive to corporations in a kind of mutual enrichment scheme.

*phrase used accidentally but pertinently

And, wishing to make themselves equally attractive to the state, corporations therefore begin (or began; this is where we are now) to adopt the state’s ideas and ideologies. Qualitatively and atmosphere-wise it’s a very different existence from life under totalitarianism, but for the masses – i.e. for everyone who isn’t a member of government or in the upper echelons of a huge corporation – some of the effects of being the subject of a repressive authoritarian state and a technocratic, consumerist-oriented one are surprisingly similar.

Classic authoritarians diminish the individuality of their subject citizens, often manufacturing laws limiting personal freedom in order to do so. The prohibition of identities, clothes, religions, media, internet access, issuing ever more precise definitions of what are to be considered societal norms of behaviour and gender roles are all steps towards an ideal state, from the point of view of its ruler. Totalitarian regimes prefer states to be peopled by those as paranoid as they are; obedient dogmatists, spies and informers; people whose lives are devoted to serving and upholding the state and the status quo and whose secret ambitions, if they have any, are most likely to revolve around joining those at the top and sharing in their almost unlimited power.

Clearly, that’s not how corporations work. But at the same time, in apparently tailoring their products more and more towards the individual – so that the customer feels catered to and begins to identify with this social media app, that phone, those brands – what they really end up doing is tailoring the public towards their products, in order to sell them more of those products and related products. And because the world of consumerism is competitive, the winning product is the one with the biggest fanbase. Looked at from the opposite direction, what this means is that the more your life as a consumer mirrors the lives of other consumers, the easier and more lucrative it is for the corporation to sell you their products. To begin with, people just used YouTube or Tiktok for entertainment; now there are people who identify with the product and ‘YouTuber’ and ‘Tiktoker’ are terms in that grey area where a profession becomes an identity.

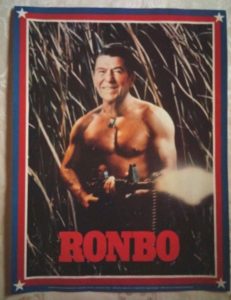

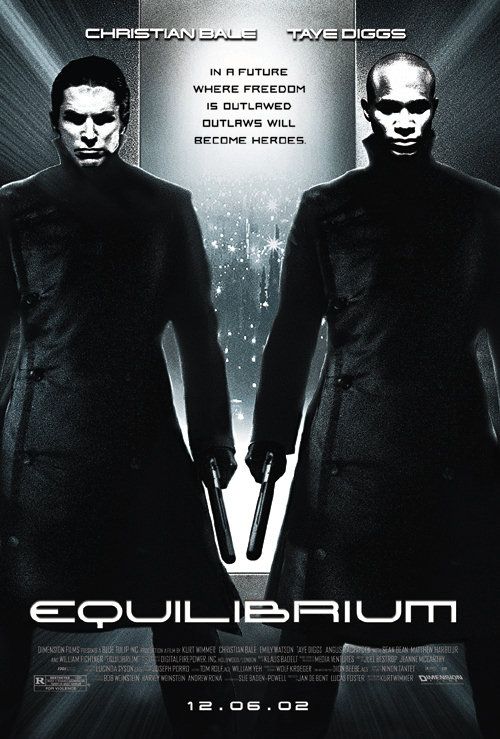

In the novels and films alluded to above, the heroic reaction to a totalitarian state or an all-powerful corporation is much the same – to rebel, to be an individual, an outsider, a non-conformist; someone who refuses to fit in their box and passively accept what they are given. But there’s a double irony here; firstly, because those rebelling-against-totalitarianism stories were popular, they were taken up by Hollywood and the entertainment industry, so that one of the defining parts of popular culture in the Western ‘free world’ has been celebrations of the victory of the individual over the faceless tyranny of the state, i.e. something that was never at that time a real worry for its audience. The second irony is that in celebrating the individuality of the heroic protagonist, what we end up with are endless, similar identikit heroes and heroines and endless variations on the same recycled stories, so that from Brave New World we end up with Logan’s Run (1976) and Equilibrium (2002) and The Island (2005) and so on, and on.

And that’s just mentioning single films: what’s notable about the Hollywood versions of these cautionary tales is that, if they are successful they become franchises; what Ripley, Sarah Connor, Murphy/Robocop, even Deckard in Blade Runner – whether or not he’s a Replicant – ultimately do is to sell the public more stories about themselves, or people like themselves.* At that point, rebelling against the all-powerful corporation becomes a trope – worse, a formula – and it stops being about non-conformity in any meaningful way and is just another way to feed the same money machine, until that story wears out and has to be put on hold for a while. In that sense only, Hollywood is at the forefront of the recycling industry; no lucrative idea is ever fully forgotten and no franchise abandoned without one eye on a possible future reboot. As I write this, another Tron sequel -in its original 1982 form the story of the struggle of the warm, human individual against the cold and faceless computer world – is struggling to find an audience.

* The visual style of Blade Runner, even more than its story has informed whole swathes of dystopian cinema, but fiction too; reading Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep its depiction of the near future is far less like Blade Runner than the works of later writers like William Gibson or almost any science fiction author since the 80s whose works belong to the near future or parallel versions of the present

Turning rebellion into money is a phrase pre-loaded with irony (yes, I get sick of mentioning irony, but it seems to be the air we breathe). I borrowed the phrase (which I’ve seen fairly recently on t-shirts and so forth) from the lyrics to the Clash’s classic 1978 single (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais, in which Joe Strummer was sneering at the Jam’s perceived commercial stance. The phrase was brought up a lot in 1991 when the Clash’s 1982 single Should I Stay or Should I Go was successfully rereleased after being licensed for a Levi’s jeans commercial. That corporate cash is hard to turn down, it seems.

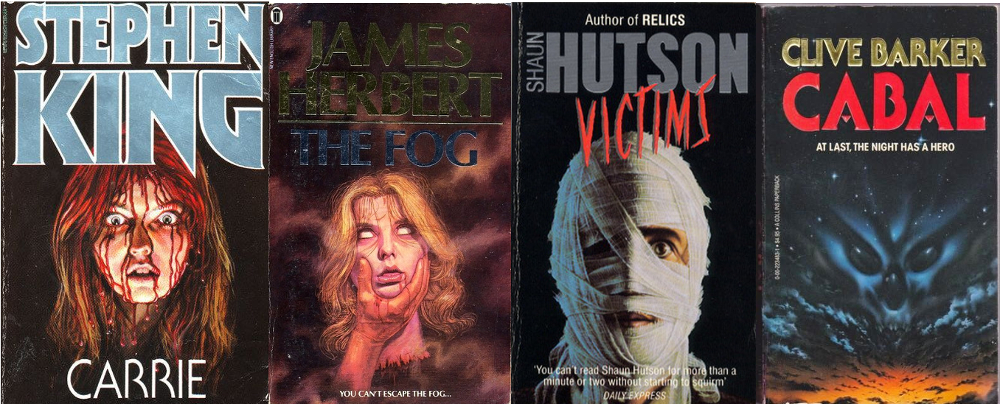

The current real world version of the corporate menace is not Replicants or state-applied repressed emotions but Artificial Intelligence (not the Spielberg/Kubrick movie). This morning I read something about how AI is not a therapist or a friend, it’s a mirror. There is definitely some truth in that, insofar as it trains itself based on its interactions with people – but more than a mirror, it’s quite important to remember that ultimately it’s a product. Interacting with it tells it’s makers what you like, just as in the past renting Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter* told Paramount Pictures or Vestron Video or whoever what you liked or – at least would accept in the name of entertainment. Finding out what you like, working out how you think, in order to sell you more of itself.

* Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter (1984) was the fourth film in the series, but hardly the final chapter – five more followed in the original series before the franchise was (briefly) laid to rest, then resurrected, in a team-up, then rebooted

It’s funny; everybody knows who the key figureheads in ‘big tech’ are – its Abelard Snazzes. Everybody knows that they are the richest men in the world and that they have political influence and that they have begun to shape their companies in response to political pressure. Things being as they are and the Western world being in an ever-accelerating self-devouring capitalist culture, it’s rarely political pressure in the form of rules or directives, but more often financial persuasion and near-money laundering; tax breaks flow in one direction and ‘donations’ (bribes) in the other.

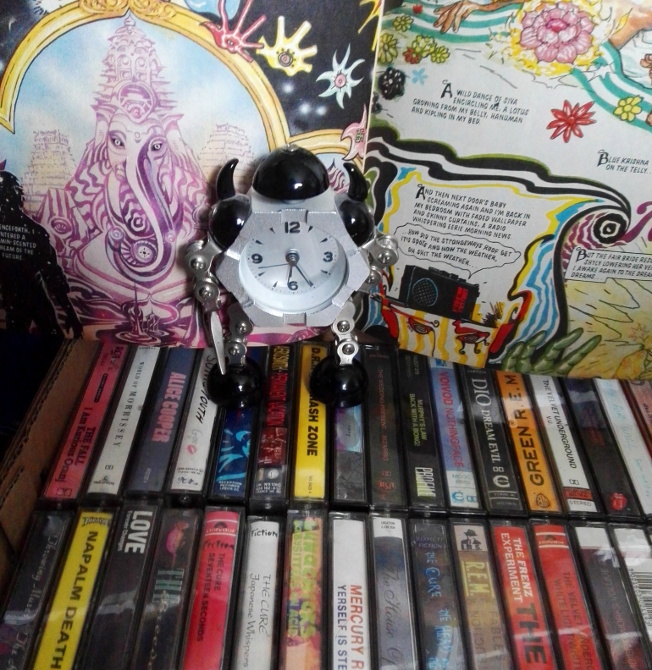

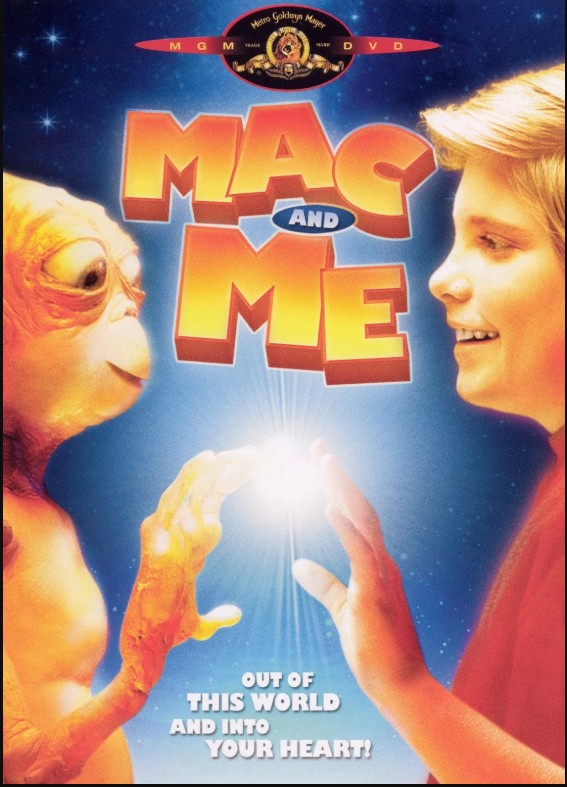

Everybody knows that these Snazz-figures made and maintain their fortunes from the tech business. So really, everyone knows – whether they choose to think about it or not – that when these men present their most ubiquitous products – be it AI bots or online tools or social media apps – free of charge, that they can’t really be free. I’m not dramatic enough (or spiritual enough) to suggest we are selling our souls, but some kind of payment is being made. And even if those tech-lords never seem convincingly genius-like, you have to hand it to them – the 1980s may have been the consumer decade, but lonely 80s teenagers never confided their problems and insecurities in a Sony Walkman, or shared their most cherished dreams with a Rubik’s cube, and they never asked a Big Mac for dating advice.