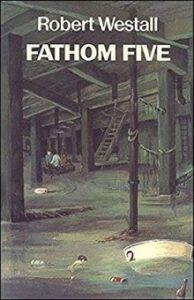

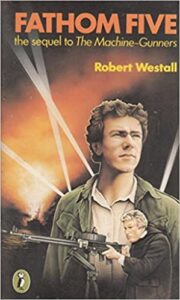

There’s a strange moment near the beginning of the 1982 Puffin Books edition of Robert Westall’s Fathom Five (1979):

Dad never talked about Life and its Meanings; only fried bread and thrushes. ‘What’s got you up so early?’ Jack told him about the thing in the water. It’ll be a mandolin, floated off a sunken ship mevve…’

Puffin Books, 1982, p.35

Strange only that is, because the hero of the book isn’t called Jack, he’s called Chas. I remember first reading this copy of Fathom Five as a child, being puzzled, then moving on. It was only some time – possibly years – later that I read the blurb on the first page, before the title page:

Robert Westall wrote this book straight after his best-selling The Machine Gunners, and it features many of the same characters that appear in the earlier novel. However, when the book was first published the names were changed. In this Puffin edition the original names have been restored.

I have always uncharitably assumed that what actually happened was that Fathom Five didn’t sell as well as Westall or his publishers had hoped and was then rebranded by them as a sequel to already successful and acclaimed The Machine Gunners in order to boost its sales, but I may be wrong. But either way, it’s apposite at the moment because a range of children’s books are being altered, apparently for various other reasons, but really for that same commercial one.

It isn’t obvious from the generally hysterical media coverage, but re-writing or tampering with “much-loved” (and that bit is important) children’s books, ostensibly to remove any possible offensiveness, has nothing to do with being PC or (sigh, eyeroll, etc, etc) “woke” – l reluctantly use the word because currently it is the word being used to talk about this issue by every moron who’s paid to have what they would have you believe is a popular (invariably intolerant) opinion. Right-wing tabloids love “woke” because it’s a single, easy-to-spell, easy-to-say syllable that takes up much less space in a headline than “Political Correctness” used to. I think there are also people who like to use it because saying “Political Correctness” feels dry and snooty and even the abbreviation “PC” has a certain technical, academic quality; but using “woke” allows them to feel cool and in touch with the times. It’s the same kind of frisson that high school teachers get (or did “in my day”) from using teenage slang or mild swearwords in front of the kids; and the cringe factor is about the same too. Hearing someone with a public-school accent decrying “wokeness” is so milk-curdlingly wrong that it’s masochistically almost worth hearing, just to enjoy the uniquely peculiar and relatively rare sensation of having one’s actual flesh creep.

But anyway, the editing of children’s books has nothing to do with people’s supposedly delicate sensibilities. High profile examples – significantly, there are only high profile examples – being of course tried-and-tested bestsellers like Roald Dahl’s Matilda and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, plus various works by Enid Blyton. “Problematic” though those books might be, the new edits are to do with money, and preventing the cash cow from dying of natural causes (fashion, essentially) like Biggles or Billy Bunter did. Parents aren’t lobbying publishers to have these books edited; “woke” parents generally don’t really want their kids reading racist or offensive books at all. And every year, untold numbers of unfashionable books (like, for example Fathom Five itself, which is great, regardless of the characters’ names) quietly slip out of print without any fuss being made. What it is, is that the books of Roald Dahl, still being adapted into films and plays and Enid Blyton, once ubiquitous enough to still have nostalgia value have made, and continue to make, a lot of money. Publishers naturally realise that some of what those authors wrote is now embarrassingly out of date and, rather than just printing a possibly-off-putting disclaimer at the front of the book, prefer to prevent any chance of damaging sales by seamlessly – well, it should be seamless, in the case of Matilda especially, it seems to be pretty clumsy – editing the book itself.

In an ideal-for-the-publishers-world no-one would even notice that this editing had been done, columnists wouldn’t pick up on it and the kids could go on requesting the books and the parents and schools could supply them and nobody would be upset. But this is precisely the type of trivial issue the (here we go again) “anti-woke” lobby loves. It has no major impact on society, no major impact on children and it has nothing to do with any of the big issues facing the modern world, or even just the UK. It also puts the right-wing commentator in the position they love, of being the honourable victims of modern degraded values, defending their beloved past. Plus, in this case there’s even – uniquely I think – an opportunity for them to take what can be seen as the moral high ground without people with opposing political views automatically disagreeing with them. Even I slightly agree with them. My basic feeling is that if books are to be altered and edited, it should be by, or at least with the approval of, the author. But it’s never quite that simple.

The reason I only slightly agree is because the pretended outrage is just as meaningless as the revising of the texts itself, it’s not a governmental, Stalinist act. The new editions of Matilda etc only add to the mountain of existing Matildas, they don’t actually replace it. If the racist parent prefers fully-leaded, stereotype-laden, unreconstructed imperialist nostalgia, it’s childishly simple for them to get it, without even leaving the comfort of their home. Better still, if they have the time and their love of the past stretches to more analogue pursuits, they can try browsing second hand bookshops and charity shops. It’s possible, even in the 2020s, to track down a copy of the original ,1967 pre-movie Charlie and the Chocolate Factory, or the most virulently offensive Enid Blyton books, not to mention long out-of-print goodies of the Biggles Exterminates the Foreigners type without too much difficulty. And in many cases one could do it just as cheaply/expensively as by going into Waterstones or WH Smith and buying the latest, watered-down versions.

But anyway, books, once owned, have a way of hanging around; I remember being mystified by Mel Stuart’s 1971 film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory the second time I saw it, at some point in the early 80s. I had known the book well since I was very young and the first time I saw the film, at home, in black and white, I thought everybody looked and sounded wrong, especially Gene Wilder, but that was all. When I saw it again, a while later, in colour, I found to my bemusement that the Oompa-Loompas were orange.* This definitely seemed odd – but even so, it’s not exactly the kind of thing that burns away at you and so it was only this year, when the book caused its latest furore, that I discovered that, although my mother had read Charlie and the Chocolate Factory to me in the late ‘70s and then I had read it myself in the early ‘80s, the edition I knew was the large-format 1967 UK hardback edition. This had Faith Jaques’s beautifully detailed illustrations – which is where all of my impressions of the characters still come from – but more importantly, it had the original Oompa-Loompas. A pygmy tribe, “imported” from “the very deepest and darkest part of the African jungle,” they were immediately controversial in the US, where the NAACP understandably took issue with them. Roald Dahl, who presumably wanted the book to sell as well in the US as it did elsewhere, agreed with them (he may have actually seen their point too, but given his character in general I don’t think it does him too much of a disservice to assume the money was the bigger issue) and changed the book. So, no problem there, even if Dahl’s solution – making the Oompa-Loompas a race of blonde, rosy-cheeked white little people, who still live some kind of life of indentured servitude in a chocolate factory – doesn’t seem super-un-problematic when you really think about it; but it was his decision and his book. The orange Oompa-Loompas were a more fantastical way around the problem, and one which enhanced the almost psychedelic edge of the film.

If the intention of publishers in 2023 is to make Roald Dahl nice, they are not only wasting their time, they are killing what it is that kids like about his books in the first place. If children must still read Charlie and the Chocolate Factory – and I don’t see why they shouldn’t – they are reading a story so mean-spirited and spitefully funny – and so outdated in so many ways – that it doesn’t really bear fixing. Though it was written in the 60s, Charlie’s poverty-stricken childhood with his extended family feels like something from the pre-war era when Dahl was a non-poverty stricken child, as does the book’s Billy Bunter-esque excitement about and fascination with chocolate. Are kids even all that rabidly excited about chocolate these days? And is a man luring kids into a chocolate factory to judge them for their sins something that can or should be made nice? I don’t think that’s an entirely frivolous point; as a child I remember Willy Wonka had the same ambiguous quality as another great figure of children’s literature, Dr Seuss’s the Cat in the Hat; which is where Mel Stuart went wrong, title-wise at least. Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory is all well and good, but it’s Charlie – a poor, harmless, nice kid who wants some chocolate – that’s the hero, not Wonka, a rich, mischievous adult man whose motives can only be guessed at. And in fact Gene Wilder captures that slightly dangerous quality perfectly. Almost all of Roald Dahl’s books are similarly nasty; but that’s why kids like them. Where necessary, a disclaimer of the ‘this book contains outdated prejudices and stereotypes which may cause offence’ (but hopefully less awkwardly worded) type is surely all that’s necessary. And anyway, where do you stop? Sanitising Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is patronising and weakens the power of Dahl’s writing, but to sanitise The Twits would be to render the whole book pointless.

*I had a similar epiphany when as a young adult I discovered that Bagpuss was pink and not the relatively normal striped ginger cat I had assumed; the joys of growing up black & white in the colour age!

Anyway; the thing that really makes the updating of books pointless is that kids who like to read, tend to read and understand. As a child in the 1980s, I had plenty of entertaining, modern-at-the-time books to read, like the Fighting Fantasy series, the novels of Leon Garfield and Robert Westall or even JJ Fortune’s slightly silly, very cinematic Race Against Time novels, but I also loved books that were much older and felt much older. I loved Capt. WE Johns’ legendary fighter pilot Biggles – especially the WW1-set Biggles books and The Boy Biggles, about the pilot’s childhood adventures in India. I loved Richmal Crompton’s William series (I wonder if William the Dictator (1938), where William and his gang decide to be Nazis is still in print? I hope so) I loved Willard Price’s Adventure series, about American brothers travelling the world to capture animals for zoos and safari parks. I even liked boarding school stories, especially Anthony Buckeridge’s Jennings books. I also remember very fondly a book called The One-Eyed Trapper by (will look it up) John Morgan Gray (1907-1978; got to love the internet) which was about (actually, the title says it all). Years later at high school, some of the poems of Robert Frost immediately recalled to me the vivid, bracing outdoorsy atmosphere of The One-Eyed Trapper, though I don’t suppose Frost would have appreciated the comparison. I was never much of an Enid Blyton fan, but I did read a couple of her Famous Five and Secret Seven books. My favourite Blytons though were the series about her lesser-known, far more awkwardly-named gang of nosy children, the Five Find-Outers (presumably it was because of that awkwardness that the names of the Five Find-Outers books were slightly bland and anonymous things like The Mystery of the Burnt Cottage etc).

These were books from the 1930s, 40s, 50s and 60s, that were set in those eras and written in outdated language and which, as they say, ‘reflected the values and attitudes of the time.’ Relatability is important in fiction up to a point, but it doesn’t need to be literal – children have imaginations after all. I didn’t want William in jeans or Jennings and Darbyshire without their school caps, or wearing trousers instead of shorts. I didn’t need Biggles to talk like a modern pilot (in fact the occasional glossaries of olden-days pilot talk made the books even more entertaining) or the one-eyed trapper to have two eyes and be kind to wildlife. My favourite member of the ‘Five Find-Outers’ was “Fatty”, which is probably not a name you would have given a lead character in a children’s book even in the 1980s. The idea that changing “Fatty” to something more tactful, making him thinner or even just using his “real” first name, Frederick – would make the books more palatable or less damaging to the young readers of today is ridiculous and patronising. And possibly damaging in itself, to the books at least. Children’s books are mostly escapism, but they are also the most easily absorbed kind of education, and a story from the 1940s, set in a version of the 1940s where the kids look and speak more or less like the children of today and nobody is ever prejudiced against anyone else doesn’t tell children anything about the actual 1940s.

I’m reminded of the recent movie adaptation of Stephen King’s IT. In the novel’s sections set in the 1950s, one of its heroes, Mike Hanlon, who is African-American, is mercilessly bullied and abused by racist teens when he’s a kid. In the movie version he’s just as bullied, but without any racist abuse. I understand why that’s being done – more explicit racism onscreen is obviously not the solution to any of the world’s problems, especially in a story which only has one substantial Black character – but at the same time, making fictional bullies and villains more egalitarian in their outlook than they were in the source material doesn’t feel like the solution to anything either. But even more to the point, there’s only so much altering you can do to a piece of writing without altering its essential character. There are many problems with the much-publicised passage in the latest edition of Roald Dahl’s Matilda where references to Kipling and so forth are replaced with references to Jane Austen etc, but the biggest one is that it just doesn’t read like Roald Dahl anymore.

All of which is to say that, whatever the rights and wrongs of it, a third party “fixing” literature (or any art form for that matter) has its limitations. I remember reading an interview with a director of the British Board of Film Classification (Ken Penry maybe?) back in the early ‘90s, discussing John McNaughton’s notorious Henry, Portrait of a Serial Killer. He was concerned about the film – though he didn’t dismiss it as worthless trash – but his main worry was that it couldn’t be meaningfully cut to reduce its horrific elements because it was the movie’s tone, rather than its content that was worrisome. A few years earlier, the BBFC had unwittingly made Paul Verhoeven’s Robocop far more brutal by editing a few seconds from the scene where the giant robot ED-209 shoots an executive for a ridiculously long time in a botched demonstration. In the original cut, the shooting goes on for so ludicrously long that it becomes pure black comedy; but cut down a little it becomes a lot less funny and therefore far nastier and (negating the point of the edit) more traumatic for a young audience. There is a reasonable argument that seeing someone get shot to death by a giant robot should be traumatic, but I’m pretty sure that wasn’t the BBFC’s motive in making the cuts, since the movie was rated 18 and theoretically not to be seen by children anyway.

A children’s novel (or at least a novel given to children to read) that comes under fire for mostly understandable reasons in American schools is The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. But though the casual use of ‘the N word’ is possibly removable, what would removing it achieve? What people are objecting to hopefully isn’t really just the language, it’s the era and the society that Mark Twain was writing about. How could you and why would you want to remove that context from the book? Making it into a story where African-Americans are, in the narrative, demonstrably second class citizens but no one ever refers to their status by using nasty names seems in a way more problematic than the racist language itself. Similarly, The Catcher in the Rye has been controversial for decades, but what difference would taking the offensive words out of it make? The only real solution, editing-wise for those who object to the ‘offensive’ material in the book would be to make it so that Holden Caulfield doesn’t get expelled from school, doesn’t hang around bars drinking while underage, doesn’t hire a prostitute and get threatened by her pimp, doesn’t continuously rant about everyone he meets; to make him happier in fact. Well, that’s all very nice and laudable in its way and it’s theoretically what Holden himself would want, but it’s not what JD Salinger would have wanted and whatever book came out of it wouldn’t be The Catcher in the Rye.

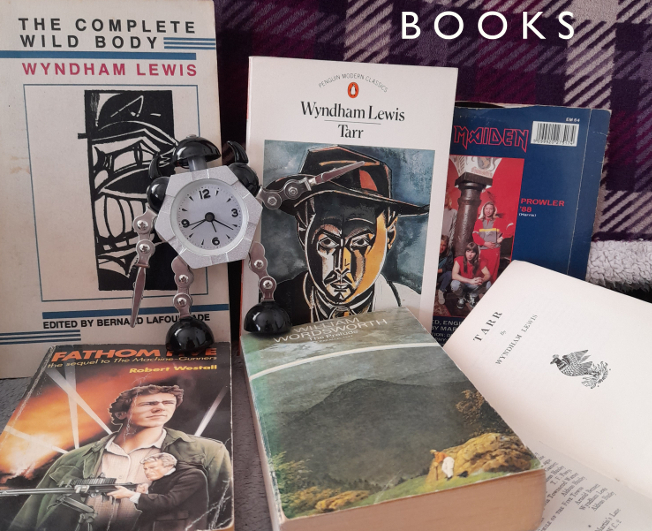

But, since there is no Stalinist attempt to destroy the books of the past, it’s not all negative. To go back to the Fathom Five example; as a kid there was something fascinating about the phantom “Jack” and had the internet existed at the time I probably wouldn’t have been able to resist trying to track down an un-revised edition of the book. I still might – but would it be worth it? Well possibly; authors and artists tampering with their old work is always fascinating, but usually it’s the revised version that is less satisfying. In the preface to the 1928 edition of his then ten-year-old novel Tarr, Wyndham Lewis wrote;

turning back to [Tarr] I have always felt that as regards form it should not appear again as it stood, for it was written with extreme haste, during the first year of the War, during a period of illness and restless convalescence. Accordingly for the present edition I have throughout finished what was rough and given the narrative everywhere a greater precision.

Reading that, you already know that the 1918 text is better, and it is. Lewis was a restless reviser of his written works, but for every improvement he made – and he did make many – he lost some of the explosive quality that keeps his often over-elaborate writing alive. As with Lewis, William Wordsworth tampered with his The Prelude – Growth of a Poet’s Mind throughout his life. Like Lewis, some of the changes he made were less to do with the character of the poem than the evolving character of the man who wrote it. The Prelude is an autobiographical work and when Wordsworth first completed the poem in 1805, he was in his mid-30s, a successful youngish poet with some lingering radical tendencies. When he completed the final version, somewhere around 1840, he was a respected, conservative and establishment figure with very mixed feelings about his wilder youth. Both versions are equally valid in their different ways and if the later version doesn’t really eclipse the first – and has shades of the orange Oompa-Loompa redesign about it – the reader is glad to have both. The point with these examples is that all remain available; if Wyndham Lewis had managed to destroy all the copies of the 1918 Tarr or Wordsworth had somehow “taped over” the 1805 Prelude the world would be a poorer place. When it comes to reworking previous triumphs (or failures) literature is no different from the other arts. Some visual artists – Leonardo Da Vinci is the classic example – can never stop messing with their work, and the film industry (think of the phenomenon of the “Director’s cut”) and the music industry frequently have these moments too. In 1988, after 8 years of complaining about the cheap production of their debut album, Iron Maiden finally decided to re-record its opening track, “Prowler” with their then-current line-up and the expensive studios now available to them. Even if original singer Paul Di-Anno hadn’t sung the song better (but he did), “Prowler ’88,” oddly tired and flabby sounding, would still be vastly inferior to the basic-but-vital original; sometimes artists just aren’t the best judges of their own work. U2’s latest venture, essentially re-recording and reworking their greatest hits, has received mixed reviews; but though one has to accept in good faith that the band thinks it was a worthwhile exercise, it’s unlikely that they have enough confidence in the new versions to replace the originals on their actual Greatest Hits from here on in.

A similar, but backwards version of the above has taken place with JRR Tolkien. A whole industry has been generated from his decades-long struggle with The Lord of the Rings, but the difference here is that the earlier material was only posthumously published. Tolkien himself probably wouldn’t have been hugely enamoured with the idea of the public reading about the adventures of Bingo Bolger-Baggins, “Trotter” et al, but as a fan it’s fascinating seeing the slow evolution of not only the book and its characters, but Middle Earth itself, with its re-drawn maps and growing sense of newly-uncovered history. In this case though, Tolkien was the best judge of his work; The History of Middle Earth is vast, an even more, but very differently, epic journey than The Lord of the Rings, but the final draft has, unlike the 1928 Tarr, a sense of life and completeness missing from all of the previous drafts and half-drafts. Partly no doubt this was because – again unlike Tarr – The Lord of the Rings remained a work-in-progress and Tolkien’s main focus for many years – the characters and setting ‘grew in the telling’ (as Tolkien puts it) and reached a kind of three-dimensional quality that is missing from most epic fantasy novels, despite Tolkien’s reticence in so many areas, notably (but not only) sex.

Alongside the concern/faux concern of “wokifying” children’s books, there’s a similar list of complaints from the usual people about the “wokifying” of TV and film adaptations of classic literature (or just literature), but here I think they are only wrong with nothing to redeem their wrongness. Firstly, because adaptations are always collaborations – and in a movie adaptation of, say, Barnaby Rudge, the artist isn’t Dickens, whose work is already complete, but those making the film. Adaptations are just that, they adapt, they don’t and can’t precisely transcribe from one art form into another. Early-Primary-School-me thought that Gene Wilder was the wrong guy to play Willy Wonka – adult me can see that in the most important way, the spirit-of-the-text way, he’s completely right. He just doesn’t look like the illustrations I knew or sound the way I thought he should sound. I would say the same (in the capturing-the-spirit sense) about Dev Patel’s David in The Personal History of David Copperfield and Fiona Shaw’s Richard II or the fact that Tilda Swinton could give a note-perfect performance as all the incarnations of the title character in Sally Potter’s Orlando. Colour and/or gender-blind casting (and all the variations thereof) can give directors and performers ways of finding the real heart of a story – or just revitalising something that has grown stale through familiarity – that conventional casting might not – and unlike replacing the word ‘fat’ with ‘stout,’ ‘large’ or ‘fluffy’ in a kid’s book, it keeps the work alive for a new audience, or even for an old one.

Secondly (I think I wrote ‘firstly’ way back there somewhere?), time, scholarship and cultural evolution give us a greater understanding of the context of a novel or play. It’s now clear that Britain, through the 20th century, back into Victorian and even medieval times and beyond, had a much broader ethnic and cultural mix than you might ever suspect from the country’s artistic record. And with that understanding, it becomes clear that characters that occasionally did appear in British fiction of the 19th century and earlier, whether Jewish, Chinese, Black, gay, whatever; tend to be represented as stereotypes to stress their otherness, but in those stories that otherness has grown rather than lessened over the years as the real-life otherness diminishes. In addition, through the passage of time, the gradations of apparently homogenous British characters, even in relatively recent fiction, tend to blend into each other.

Nowadays, Dickens seems to many of us to be full of rich and poor characters, but for Dickens’s audience the social differences between the upper, upper-middle, middle, lower-middle, working and under-classes would seem far more marked than they do today and therefore even a caricature like Fagin in Oliver Twist would be part of a far richer tapestry of caricatures than now, when he stands out in ever more stark relief. We can’t, hopefully don’t want to and anyway shouldn’t change the novels themselves – indeed, the idea of a modern writer being tasked with toning down the character of Fagin or Shylock in The Merchant of Venice highlights how ridiculous the treatment of children’s books is, as well as the devalued position they have in the pantheon of literature. But in adapting the works for the screen, the truer a picture we can paint of the society of the time when the works were written or are set, the more accurately we can capture what contemporary audiences would have experienced and perhaps gain more of an insight into the author’s world-view too.

Thirdly, and on a more trivial level; why not make adaptations more free and imaginative, not only to give a more accurate and nuanced picture of the past, or to ‘breathe new life’ etc, but just for the joyous, creative sake of it? The source material is untouched after all. Fairly recently, a comedian/actor that I had hitherto respected, complained online about the inclusion of actors of colour in an episode of Doctor Who, in which the Doctor travels back in time to London in some past era, on the grounds that it was ‘unrealistic.’ Well, if you can readily accept the time-travelling, gender-swapping Timelord from Gallifrey and its logic-defying time/space machine, but only for as long as olden days London is populated entirely by white people – as it probably wasn’t, from at least the Roman period onwards – then I don’t know what to tell you.

So maybe the answer is yes, change the books if you must; remove the old words and references, make them into something new and palatably bland as fashion dictates – just don’t destroy the old ones and please, always acknowledge the edits. Let the children of the future wonder about that strange note that says the book they are reading isn’t the same book it used to be, and maybe they will search out the old editions and be educated, shocked or amused in time; it’s all good. But until it happens to obscure books too, let’s not pretend the motives for ‘fixing’ them are purely humanitarian.

sophisticated, articulate, menacing but not unfriendly. A few years later, when I began to read

sophisticated, articulate, menacing but not unfriendly. A few years later, when I began to read  And that’s just the lyrics; another thing about The Fall that made an impression on me early on was that, although MES was incredibly fussy and perfectionist about the band’s music, he wasn’t snobbish in the usual way; no tune, if it was catchy, was too silly for Mark E. Smith. Think of the speedy but somehow miniature-sounding rock guitar on ‘Underground Medicine‘ or loping, bouncy beat to ‘Gramme Friday‘ or the oddly jaunty, countryish ‘Fit And Working Again‘. or the kazoo on ‘The North Will Rise Again‘– this was ‘angular’ (the definitive descriptive term for late 70s/early 80s UK indie rock) if you like, but it was not standard ‘post-punk’ music, nor was it (as it could easily have been) twee in that beloved ramshackle UK indie/C86 kind of way. Perhaps because Mark E. Smith was not (99% of the time) a melodic singer, the band could play anything behind him and it sounded right. When, at the beginning of one of my favourite songs, ‘Slates‘, MES shouts ‘this is the definitive rant‘ he’s nailing part of the charm of his work. As long as the rant was in place, no tune was too small, too jingly or too silly to make something worthwhile out of.

And that’s just the lyrics; another thing about The Fall that made an impression on me early on was that, although MES was incredibly fussy and perfectionist about the band’s music, he wasn’t snobbish in the usual way; no tune, if it was catchy, was too silly for Mark E. Smith. Think of the speedy but somehow miniature-sounding rock guitar on ‘Underground Medicine‘ or loping, bouncy beat to ‘Gramme Friday‘ or the oddly jaunty, countryish ‘Fit And Working Again‘. or the kazoo on ‘The North Will Rise Again‘– this was ‘angular’ (the definitive descriptive term for late 70s/early 80s UK indie rock) if you like, but it was not standard ‘post-punk’ music, nor was it (as it could easily have been) twee in that beloved ramshackle UK indie/C86 kind of way. Perhaps because Mark E. Smith was not (99% of the time) a melodic singer, the band could play anything behind him and it sounded right. When, at the beginning of one of my favourite songs, ‘Slates‘, MES shouts ‘this is the definitive rant‘ he’s nailing part of the charm of his work. As long as the rant was in place, no tune was too small, too jingly or too silly to make something worthwhile out of. lot of it, and it was mostly pretty affordable, especially the stuff from the band’s then slightly maligned, now justly celebrated mid-80s period of relative commercial success. In itself, that success was odd and underlined just how unique the band, and specifically Smith’s vision, was. I loved that Mark E. Smith saw nothing elitist or strange about working with a ballet company, or in writing for the theatre and working with ‘serious’ artists and yet the people I knew who derided Morrissey as being “poncy” never seemed to think that about MES. The fact that he refused to separate the ‘high’ arts from his work with The Fall was so powerful. Everyone knows, for example, that Brian May is an astrophysicist, but imagine if astrophysics had somehow been indivisible from his work with Queen; they would have been far a more peculiar and far less successful, but also (with no offence intended to the band or its members) probably more interesting band.

lot of it, and it was mostly pretty affordable, especially the stuff from the band’s then slightly maligned, now justly celebrated mid-80s period of relative commercial success. In itself, that success was odd and underlined just how unique the band, and specifically Smith’s vision, was. I loved that Mark E. Smith saw nothing elitist or strange about working with a ballet company, or in writing for the theatre and working with ‘serious’ artists and yet the people I knew who derided Morrissey as being “poncy” never seemed to think that about MES. The fact that he refused to separate the ‘high’ arts from his work with The Fall was so powerful. Everyone knows, for example, that Brian May is an astrophysicist, but imagine if astrophysics had somehow been indivisible from his work with Queen; they would have been far a more peculiar and far less successful, but also (with no offence intended to the band or its members) probably more interesting band. Although most of my favourite Fall albums are the early ones (especially Dragnet, Grotesque (After The Gramme) and Hex Enduction Hour) those 80s albums with the Mark and Brix-led lineup(s), especially The Wonderful and Frightening World Of The Fall are pretty unassailable and perhaps the least overtly commercial ‘commercial’ period of any band I can think of. The band stayed good though, and although I am not a Fall completist (a vocation rather than a hobby) I’ve found that any Fall record one picks up will have something great on it; and there aren’t many bands with a 40 year career you can say that about.

Although most of my favourite Fall albums are the early ones (especially Dragnet, Grotesque (After The Gramme) and Hex Enduction Hour) those 80s albums with the Mark and Brix-led lineup(s), especially The Wonderful and Frightening World Of The Fall are pretty unassailable and perhaps the least overtly commercial ‘commercial’ period of any band I can think of. The band stayed good though, and although I am not a Fall completist (a vocation rather than a hobby) I’ve found that any Fall record one picks up will have something great on it; and there aren’t many bands with a 40 year career you can say that about.