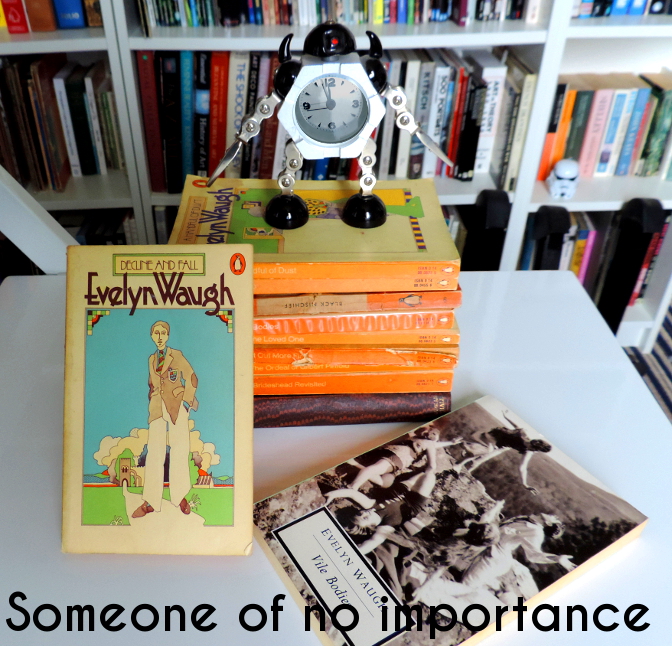

The news that one of your favourite novels is being made into a film or TV show is never straightforwardly pleasurable; yes, there’s an excitement about seeing scenes from the page (and from your own imaginings of them) on screen, but there’s a certain amount of apprehension too. Nobody will look right (at first anyway), they may not sound right, and if you don’t like them you may be stuck with them whenever you re-read the book (especially if you didn’t have a particularly clear image of them in your mind in the first place or if, like me the image you do have often bears strangely little relation to the writer’s actual descriptions). Then there’s the tone and authorial voice/point of view, the inner life of the characters… It’s actually surprising there are any good adaptations of books. But there are many, the best of which (to me at least) are those that capture the essence of the book without necessarily being ‘faithful adaptations’ (Catch-22, Ghost World) or which use the book as a launchpad for the filmmakers’ own ideas (Blade Runner, Jaws). Most adaptations are of course neither of these. Which brings us to the BBC’s ‘not bad’ version of Evelyn Waugh’s Decline and Fall.

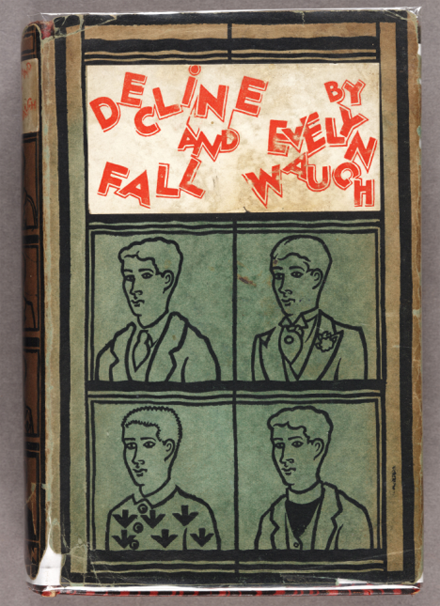

It’s first of all a strange book to have chosen; a black comedy whose fans – as with fans of JG Ballard’s Crash, William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch and Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho – know in advance to expect an approximate, rather than precise rendering of. Decline and Fall is not an extreme book in the graphic sense that those three are, but, like at least two of them, its humour is grounded in its unremitting unpleasantness and in the end it’s a bleak, essentially misanthropic, nihilistic kind of comedy, tellingly completed before Waugh’s conversion to Roman Catholicism. For a variety of reasons, though, ‘bleak’ isn’t how the TV version feels.

But before moving on to the show, it’s worth looking at why the book is the way it is. Firstly, and most importantly, it’s an exaggerated reflection of certain aspects of its creator’s personality and an expression of his sense of humour. Even post-conversion, when there is a modicum of compassion for some of the characters in his work, Waugh’s books – with the exception of Brideshead Revisited – are mostly funny but extremely mean-spirited black comedies full of caricatures and snobbishness made extremely funny by his writing style, and in his first few novels that’s pretty much all there is. The surprising depth of feeling in even these books comes from the fact that Waugh allows that his characters – even a relative cipher like Decline and Fall’s bland non-hero Paul Pennyfeather – have human emotions, even if they are rarely respected by others or the author. In Decline and Fall , the snobbishness, misogyny and the – to modern readers – strange treatment of child abuse in which certain pupils seem partly culpable in their encouragement of the paedophile (I hope that most of us would now agree that the victim of child abuse can’t really be complicit in it), can be explained pretty simply: it was the milieu that the young Waugh knew. His education at an all-boys public school and his subsequent university life and work as a teacher in (again) an all-boys public school were overwhelmingly male experiences and child abuse was, if not actually legal or even acceptable, then at least a tacitly accepted if not much written about part of public school life. Nowadays, we might find it odd for a writer to include that kind of thing in a book where the original author’s note reads ‘Please bear in mind throughout that IT IS MEANT TO BE FUNNY.’ but although the novel was self-consciously outrageous, the aspects that most trouble modern readers; abuse, misogyny, racism, were probably not that much dwelt upon in the late 20s.

The reason that Waugh’s comedies are so rarely successfully adapted into other formats is that their action is farcical, but not complicated. In 1920s comedy, PG Wodehouse is the obvious star, and his work lends itself naturally to stage and television adaptation thanks to his intricate joke-like plots (complete with a punchline at the end). The comedy is there in the story and the writer’s style is the dressing that brings it to life. Waugh’s early plots meanwhile are loosely constructed to non-existent and chaotic and often implausible (yet somehow also more realistic than Wodehouse) and his writing style is everything. It’s a weird, slightly unworkable comparison, but now that I’ve made it; with Wodehouse, his stories are like a kind of pantomime or fairytale, played out by characters the author loves and which are completely ludicrous but make perfect sense on their own terms. With Waugh, it’s often as though a real (perhaps even tragic) story about real people is being told by someone who finds the whole thing funny and has little to no sympathy for the fools and the predicaments they find themselves in. Wodehouse orchestrates the events like a stage director, while Waugh reports them like a condescending gossip. To me, he is the funnier of the two, but his presence is also necessary; if you remove Wodehouse the narrator from his stories, you are left with characters that embody the warmth and silliness of the narrator’s voice, acting out stories which are in themselves funny. If you remove Waugh you are left with people you never really know making fools of themselves in painful ways. If you had never read Waugh but only watched adaptations of his work, one might expect his books to read something like a posh version of Tom Sharpe; which they definitely don’t.

The other main reason that Waugh’s early books are the way they are is because he was part of that couple of generations who lived through the First World War, but who were too young to take part. The impact this had is undeniable and the British literature of the 20s and 30s is filled with very different books by very different writers which nevertheless have various things in common with each other and which I like very much. The early 21st century may be in some ways a far more cynical time than the 1920s, but in effect it is both nicer and nastier. Most of us no longer accept the inequalities of the class system, or discrimination in race and gender. We are also no longer surprised that human beings can slaughter each other in their millions in mechanised ways; but while being used to that idea, it’s also true that, unlike Waugh’s generation, we (at least we in the UK) haven’t had the experience of half of the adult males that were there in our early childhood simply not existing anymore, or living in a country where almost every town and village doesn’t have a monument to those killed in a war we remember. A large part of the literature of the 20s and 30s consists of writers either trying to find meaning in a society whose way of life has been changed forever, whose old beliefs; in religion, in tradition, no longer seem to have any meaning, or of trying simply to escape the realities of modern life altogether. In the mid-to – late 1930s, politics would take centre stage in British literature, but for a period from around 1920 to 1935 the anxieties of the country’s younger writers were revealed in a series of strangely formless but oddly similar novels, which were once labelled ‘futilitarian’.

These are my favourites, might as well do this chronologically…

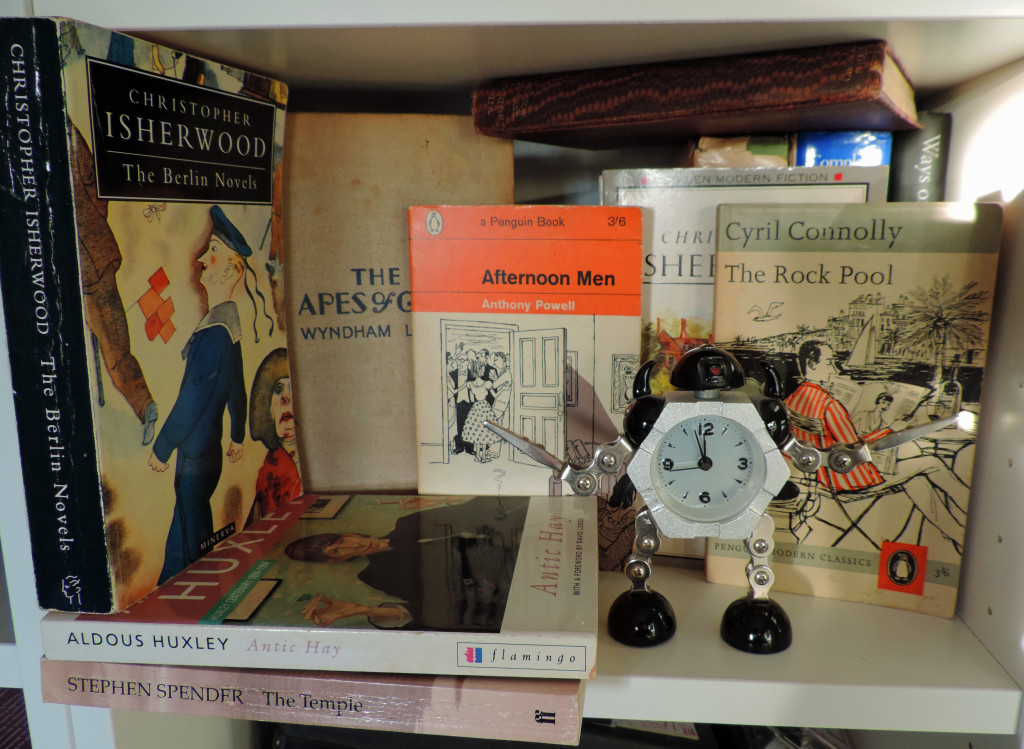

Aldous Huxley – Crome Yellow (1921), Antic Hay (1923) and Point Counter Point (1928)

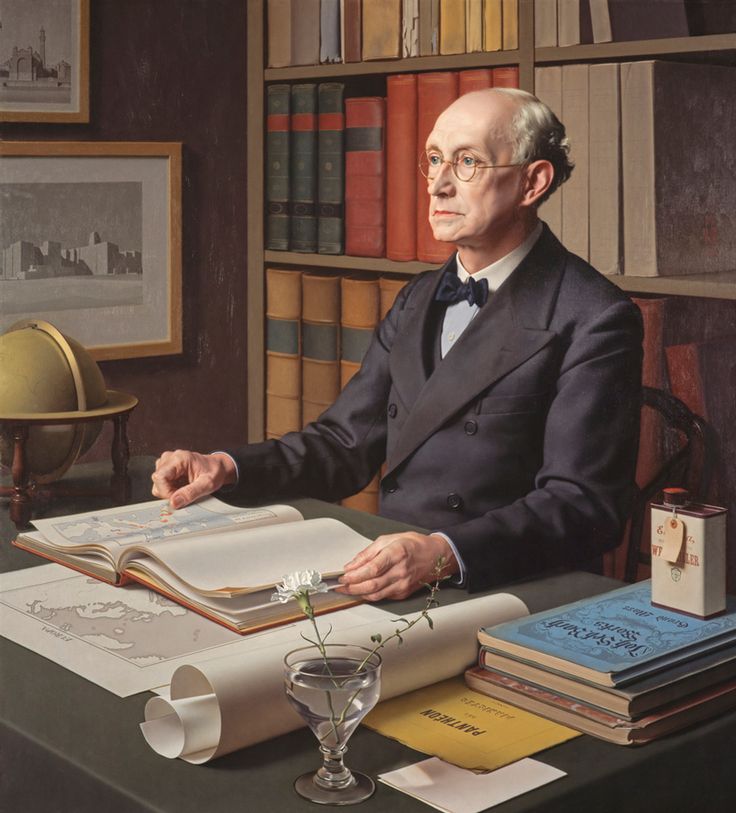

Huxley was in fact slightly older (20 when WW1 broke out, whereas Waugh was only 11) but he could not take part in combat due to his chronically bad eyesight. His early novels (I think Antic Hay is the best) make a very interesting comparison with Waugh’s, because at first they seem fairly similar; modern comedies where the storylines (such as they are) mostly revolve around the social lives of young, wealthy and irresponsible people. But the tone and content is very different. While Waugh was at school during WW1, with not only all the jingoism and propaganda that that entailed, but also the noticeable absence of adult male teachers and role models, for Huxley, WW1 was the period of Bloomsbury (he worked as a farm labourer at Garsington Manor, home of the society hostess and patron of the arts Lady Ottoline Morrell. For him, social life meant intellectual conversation; the discussion of art and modernism, conscientious objection, philosophy, pacifism. The comedy in novels like Antic Hay comes mainly from his satirical portrayals of the kinds of people he was mixing with but they are funny in both a broad way (the hero Theodore Gumbril’s invention of ‘pneumatic trousers’) and a deeper one (relationships and their difficulties). The main difference from Waugh is that whereas the comedy in a book like Waugh’s Vile Bodies arises from the somewhat desperate attempts of the main characters to have fun in the face of the meaningless void underlying modern life, in Huxley’s works the comedy arises from the characters’ often farcical and pretentious attempts at finding meaning through conversation, art and philosophy. The contrast between Huxley’s novels and an apparently very similar one – Wyndham Lewis’ great satire The Apes of God (1930) is especially striking because the milieu the books are set in almost identical (they knew many of the same people) and because, like Huxley, Wyndham Lewis was not nihilistic. He was however, immensely negative and the fact that he had seen active service in WW1 and was also himself a pioneering artist made him extremely impatient with what he saw as the wishy-washy dilettantism of the Bloomsbury artists and writers and their detachment from real life. The contrast between Antic Hay and The Apes of God is the difference between an affectionate Max Beerbohm cartoon and a merciless James Gillray caricature.

Evelyn Waugh – Decline and Fall (1928) and Vile Bodies (1930)

What makes these books distinctively post-WW1 is the nihilism at their heart. The younger generation of the 1920s were probably more different from their parents (products of the Victorian era) than any generation before or since (excepting maybe that of the 60s) and the tone of Waugh’s novels is resolutely modern and, despite its insistence on/preoccupation with social class, the feel is one of fragmentation and instability, especially in comparison with pre-War literature. When older people are presented, it is almost always as an archaic survival from a distant era. If the war is mentioned at all, its in an almost nostalgic way by people for whom it was the backdrop of their youth or childhood. The most surprising thing about Waugh’s books is the unexpected poignancy that comes from his mostly unsympathetic handling of his characters; Vile Bodies, probably his most determinedly unpleasant book, is also his funniest (aside from the grotesque later masterpiece The Loved One).

Anthony Powell – Afternoon Men (1931)

Of all the books here, Afternoon Men feels perhaps the least ambitious, but makes me laugh the most. I have read some of Anthony Powell’s other books (and started but not finished his Dance to the Music of Time series), but they just aren’t the same. The story is almost identical to those of Huxley and Waugh – a group of young people meet up socially and drink a lot, have affairs etc – although the social class of Powell’s protagonist William Atwater is lowly enough that he actually has a normal, office-based job – a rarity in any of these books. Atwater’s friends and acquaintances are the usual mixture of bohemian high society people but it is Powell’s abrupt, lightly modernistic writing style and feel for dialogue that makes it work so well:

“’I work in a museum’, said Atwater. He was getting sleepier and felt he ought to say something. He had begun to be depressed.

‘That must be very interesting work, isn’t it?’

‘No.’

‘Isn’t it really?’

‘I often think of running away to sea.’

‘I think it must be very interesting.’

‘Do you?’

* * * *

‘What about your books?’ Atwater stood up. He could not do all the stuff about the books. He was too sleepy. He said:

‘There are these. And then there are those.’”

(Afternoon Men, p.35-6, 1963 Penguin edition)

As a writer, Powell is far more deadpan and less misanthropic than Waugh, but he creates a similarly poignant effect; it would be quite possible to film this novel and, used verbatim, the dialogue might still be funny, but what essentially makes the book work is the style in which it is written.

Cyril Connolly – The Rock Pool (written 1935. published 1936)

The Rock Pool is the only novel by Connolly – best known as a literary critic – and it is one of my favourite books. Connolly was the same age and (more or less) social class as Evelyn Waugh, and the novel is the portrait of a snobbish young man of means who goes to the French Riviera to observe life in an artist’s colony, with the explicit intention of writing a period piece about the kind of carefree1920s-style life of leisure that no longer existed in the London of the 30s, but might still be going on there. In fact, it isn’t – and instead he finds himself drawn into the lives of the impoverished artists, conmen and bar owners there until it becomes clear that he is not the detached ironic observer he imagined, but has in fact found his niche and his people, whether he wants to have or not. In comparison with Waugh and even Huxley, Connolly is far more sympathetic to his characters and the tone is completely different from Waugh’s slightly contemptuous detachment:

“’Tell me, why do you come here if you are such a snob?’

‘Who said I was a snob?’

‘Why, everybody… I’m sure it must be very amusing.’

He felt old and miserable, going through life trying to peddle a personality of which people would not even accept a free sample.”

(The Rock Pool, p.90-91, Penguin edition, 1963)

The fact that The Rock Pool is a product of the mid-30s and not the 20s is part of its charm. While Connolly’s contemporaries and peers were becoming interested in philosophy and science (Huxley), religion (Waugh) or politics and social commentary (George Orwell, Christopher Isherwood, WH Auden etc), Connolly accepted, with insight, the aimless, aesthetic worldview of his 20s generation, even as it became obsolete.

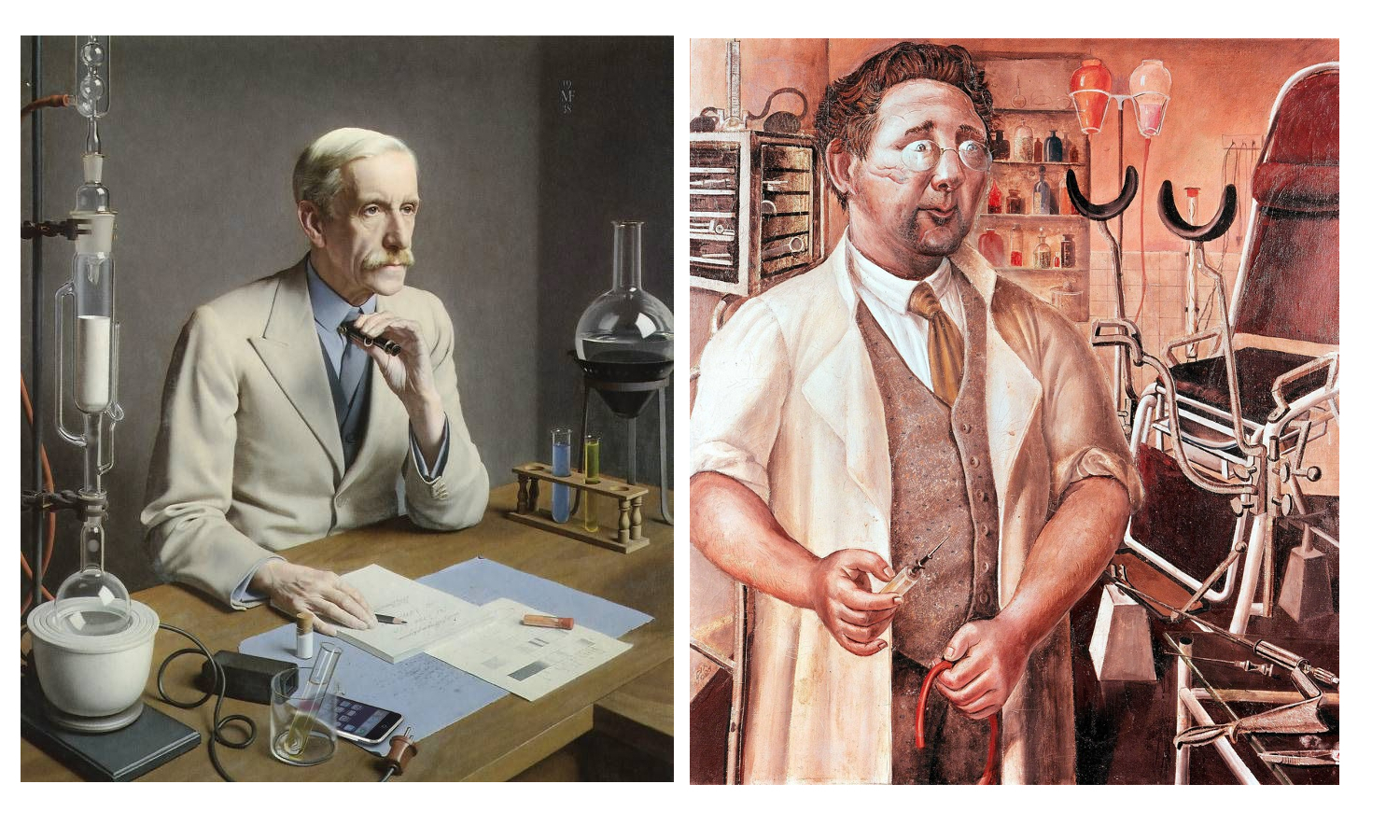

Christopher Isherwood – Mr Norris Changes Trains (1935)

Isherwood’s first two novels, All The Conspirators (1928) and The Memorial (1932) are also relevant here, but Mr Norris… (probably best known, with its semi-sequel Goodbye To Berlin (1939) as being the inspiration for the musical Cabaret) have more in common with the books described above. While both of his earlier books dealt specifically with the generation gap that had resulted from the First World War (and The Memorial is explicitly concerned with the effects of WW1 on British society), Mr Norris is, although very different in tone, essentially similar to The Rock Pool – a comical story about the adventures of a young upper class person out of his element. Although famous for its evocation of the politics and life of late Weimar and early Nazi Berlin, the novels were born from Isherwood’s desire – in 1929/30, rather than the mid-late 30s of the novels – not for any kind of social or political commentary, but to escape the milieu of upper class England and experience the hedonistic lifestyle of Berlin. As with most Waugh and Powell, the book’s main protagonist is less vividly drawn than the more extreme characters who surround him, and in many ways Isherwood accomplishes a kind of heightened, occasionally grotesque realism something like the Neue Sachlichkeit artists (Otto Dix, Georg Grosz, Rudolf Schlichter, Christian Schad etc) who were working in Germany in the same period, and whose paintings have often adorned the covers of his books. The fact that his books are partly autobiographical (and written in the first person, as ‘William Bradshaw’, Isherwood’s own middle names) means there is little of the distancing effect of Waugh and although there is much humour in Isherwood’s early novels, often at the expense of his characters, they are written with a warmth and compassion that makes them translate to the screen without losing too much of the feel of the novel – with the exception of the narrator himself, who suffers by being mostly a nondescript bystander, so that in Cabaret, the Christopher Isherwood/William Bradshaw character has to become the very different Brian Roberts.

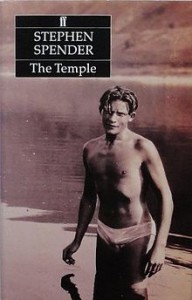

oh – not chronological now, but also – Stephen Spender – The Temple (written 1929, published 1988)

While Isherwood was in Berlin with WH Auden, their friend Stephen Spender found his way to Hamburg, seeking not only the hedonistic freedom of Weimar Germany, but also freedom from censorship. As Spender wrote in the introduction to the (very) belated first edition of The Temple, England in 1929 was a country where James Joyce’s Ulysses was banned, as was Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness. In going to Germany, his motives were at least partly artistic, and as he noted, “The Temple is pre-thirties and pre-political.” The same could be said of all of the novels discussed here. In that sense, The Temple sits strangely, but appropriately, in the company of the books of Waugh, Anthony Powell and co. In comparison with Isherwood’s Berlin stories, Spender’s novel is far more concerned with the inner life of its narrator and his Hamburg is less vividly drawn, but at the same time the book is far more explicit about sex than Isherwood (though to be fair Spender revised The Temple before publication in the 80s so it isn’t clear how much of the explicitness existed in 1929 – enough to prevent it from being published though). It’s a summery, if slightly troubled book, not improved by the author’s retrospective awareness of how fleeting the freedom it describes would be. Also, although Spender was himself far from humourless, there’s an earnest quality that makes the tone of the book unique in this list; it’s far more of a considered portrait of a time, than a story about some young people.

Decline and Fall – the TV show

So, finally – to that TV adaptation of Decline and Fall. It wasn’t actually bad at all (vastly better than the mystifyingly titled 1969 movie adaptation, Decline and Fall…of a Bird Watcher), but despite all the positive reviews it wasn’t (to me anyway) right either; how come? Firstly, the book was published in 1928 and had a contemporary setting. That means that it is now a period piece, which on the screen, gives an instantly distancing effect. The twenties in particular (actually, the twenties and thirties; TV rarely discriminates between the two) has evolved a certain lighthearted and somewhat cosy screen presence on television over the years, from the nostalgic adaptation(s) of Waugh’s very different Brideshead Revisited to gentle Sunday evening drama of The House of Elliot to Jeeves and Wooster and even You Rang M’Lord.

Thanks to these shows and others like them (not to mention films like Bugsy Malone and The Great Gatsby in its various versions) there’s a kind of visual shorthand for the twenties, consisting of; striped blazers, flapper fashions, art deco, the Charleston and hedonistic and/or gormless aristocrats, the fantasy of being independently wealthy, plus the odd Moseley-inspired fascist and monocled lesbian; all of which fits Decline and Fall pretty well, in a superficial kind of way. But while nostalgia is, appropriately, an element in all of the aforementioned programmes (not so much The Great Gatsby, ironic given how the film version traded on the visual aspects of its high society settings etc), it should really have no place in Decline and Fall. Nostalgia can’t help being present though, just through the accumulation of period detail and the kind of broad acting that a comedy set among the upper classes in the 20s seems to require. This broad approach is again fair enough in a way, since Decline and Fall is essentially a novel where the characters are close to being caricatures anyway.

The most obvious place the book differs from the television adaptation is that in the book, the mostly innocent and bland fish-out-of-water main character, Paul Pennyfeather doesn’t have to be – and often isn’t – particularly likeable; the reader doesn’t have to like him or identify with him to find his story funny and anyway, Waugh makes it explicit that we are not seeing Pennyfeather at his best or most typical or indeed in his element at all. Considering the ridiculous (and at times heartbreaking) circumstances he finds himself in, his outbursts of bitterness are surprisingly few and far between. Presenting a not-very-likeable character having misadventures with even less likeable characters is not, however a particularly ratings-grabbing idea, so it’s not surprising the BBC didn’t play it that way. It would never have occurred to me to cast the comedian Jack Whitehall in the leading role, but the hapless/diffident/youthful/naive sides of Pennyfeather’s nature are not that far removed from Whitehall’s usual persona and I don’t mean it as an insult when I say he captures the somewhat one-dimensional, nonentity-like aspect of Pennyfeather quite well.

But, in the bigger picture, the fact that the BBC is spending money on an Evelyn Waugh adaptation at all may not really be a good sign. As Jon Savage wrote in 1986 (re. the TV adaptation of Brideshead Revisited):

“Waugh’s elevation into legend – as the house god of literary London – has come at the same time as, and may have fuelled, a concerted ideological attack on the social gains of the whole post-war period.” (Jon Savage, Waugh Crimes, The Face, September 1986, in Time Travel – Pop, Media and Sexuality 1976-99, Chatto & Windus 1996, p. 206).

The adaptation of Decline and Fall in 2017 says as much about the current rise of conservatism as the success of Brideshead Revisited did about Margaret Thatcher’s mid 80s, both about the nature of the conservatism itself, and the ways society has changed since the last strengthening of the right. The choice of Brideshead to capture a conservative zeitgeist was an obvious and safe one; Waugh’s least characteristic, if most successful novel, it is (or at least it can be easily adapted as) a straightforward nostalgic paean to/romanticisation of the leisured life of the aristocracy in the pre-WW2 period, the last time they could be seen as the leaders of fashion and in a real sense ‘the ruling class’, with an Empire and subordinate classes to (literally) ‘lord it’ over. Then as now, the appeal of traditional ‘Britishness’ was strong, both with the kind of conservative, older elements in society/in charge and those who see progressiveness only in terms of threatening change/instability. Back in 1986, the ‘golden age’ of Brideshead Revisited was still remembered by the older generations, including many who were still active in the political life of the country.

But although the BBC made a costume drama, perhaps the most conservative television form, and although Waugh was a lifelong conservative and reactionary, Decline and Fall the novel, as discussed above, is hardly conservative at all; it doesn’t stand for anything, and its guiding principle seems to be that people are foolish and stupid and ruin their own lives and the lives of others without caring or even noticing. It’s a book which mostly gets away with its casual misogyny and racism because of its overwhelming misanthropy; if these people are laughable and stupid and ridiculous then at least he doesn’t show us anyone that isn’t; the fact that one of the book’s most likeable comic characters is a teacher who is not only a bad teacher, but a serial child abuser shows just what an odd choice it is for a BBC costume drama. The way the BBC tackled the more problematic aspects says a lot about where society is in 2017. In the novel, the (in modern terminology) paedophile teacher Captain Grimes’ abuse of the children in his care is seen by the other characters as distasteful and disreputable, as well as criminal, but is still seen as something one can be funny about. Somewhat surprisingly, this element made it to the screen more or less untouched, albeit without the flirtatiousness of Grimes’ favourite victim (as we, but not he, would see it), Clutterbuck. It is interesting though, to note that when reviewing the show, the word paedophile has almost always been replaced by the equivalent but somehow less inflammatory word ‘pederast’; somehow enjoying the comical exploits of a fictional paedophile might not be okay. It’s presumably the respectability of the source material (Decline and Fall may be outrageous, but Waugh is a pillar of British literature), the broadness of the comedy and the relative vagueness of the acts that makes it acceptable. And I think that’s right in a way; the element is there in the novel, it’s supposed to be and is uncomfortably funny in the novel (Waugh really was a kind of anti-Wodehouse at that point in his career), even though child abuse itself is obviously not funny. It can be assumed I think that the makers of the programme are not condoning anything, and hand-wringing self-censorship would not make the programme better; but there seems to have been a certain amount of that anyway, as we shall see.

As the misanthropy of the novel is reduced in the TV version largely because of Jack Whitehall’s sympathetic portrayal of Paul Pennyfeather, the misogyny of the book more or less evaporates onscreen, largely because the female characters are no more or less caricatures than the male ones, and are played by real women. In the book, the women are mostly predatory in one way or another and are strictly there to be admired, feared or despised – and the admiration always ends in disillusion. In Waugh’s mature books (even his best ones like A Handful of Dust) it could be argued that this feeling never significantly changes.

Where the BBC seems to have been most squeamish is with the novel’s racism. Although the anti-Welsh feeling made it to the screen more or less unchanged and again, partly neutralised by the fact that almost all of the characters were played so broadly, the episode featuring Margot Beste-Chetwynde’s African-American boyfriend Sebastian “Chokey” Cholmondley is more problematic. In the adaptation, Chiké Okonkwo plays the character exactly as written; he is articulate, urbane and enthusiastic about ecclesiastical architecture; but, when he says in the novel, “You folk think that because we’re coloured we don’t care about nothing but jazz. Why, I’d give all the jazz in the world for just one little stone from one of your cathedrals”, it’s supposed to be funny, not just because of the naivety of the lines, but because they comes from a black character. His entry into the book as Margot Beste-Chetwynde’s companion at the school games sets the tone for the whole episode:

“’I hope you don’t mind my bringing Chokey, Dr Fagan?’ she said. ‘He’s just crazy about sport.’

‘I sure am that,’ said Chokey.

’Dear Mrs Beste-Chetwynde!’ said Dr Fagan; ‘dear, dear Mrs Beste-Chetwynde!’ He pressed her glove, and for a moment was at a loss for words of welcome, for ‘Chokey’, though graceful of bearing and irreproachably dressed, was a Negro.” (Decline and Fall, p. 75)

Throughout the scene that follows, Chokey talks about church architecture, music and his race, and did so in the TV version, but the fact of his articulacy and the idea that his presence among high society people is in itself funny remains inescapable in the novel. Also, what the BBC understandably didn’t include, was the way that almost every other character present comments on Chokey’s presence, or the abusive terms they use when doing so. I’m not sure what else they could have done while remaining at all true to the novel. On the one extreme, removing the single black character from a TV show in the name of not upsetting people with racism would make no sense, and on the other, having Jack Whitehall say, as Paul Pennyfeather does in the novel, “I say Grimes, what d’you suppose the relationship is between Mrs Beste-Chetwynde and that n—–?” would – to say the least – have spoiled the show and made Pennyfeather a less sympathetic character than the BBC want him to be. But possibly they should have?

When writing about Waugh in 1986, Jon Savage wrote;

“It is extremely important that British culture develops a way of addressing the present and the future rather than the past, that recognises our pluralistic, multiracial society and our position, finger-in-the-dyke of trends in world politics” (Time Travel – Pop, Media and Sexuality 1976-99, Chatto & Windus 1996, p. 207)

and that’s still true – indeed, it’s more true now than it was even five years ago. But Decline and Fall isn’t it. Obviously, its anarchic vision isn’t as straightforwardly nostalgic and conservative in 2017 as Brideshead was in the 80s, but that’s partly because popular culture, post-Brass Eye, post-I’m A Celebrity and post-Operation Yew Tree is massively more coarse and more receptive to deliberate bad taste than the 80s was, or the 20s were for that matter. In its concern with period detail and its twee Jeeves and Wooster-ish execution, the makers of Decline and Fall have swapped the viciously funny nihilism of Waugh’s 1920s for a slightly cosy bad taste pantomime world which is equally as uncomfortable in its own very different way and leaves a comparable, but again different funny taste. Still; it wasn’t awful.

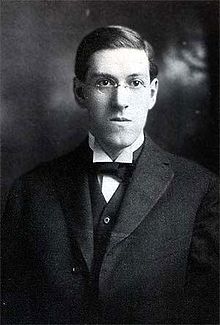

It’s approximately 90 years since HP Lovecraft wrote, “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is the fear of the unknown.” (in the essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1926-7)), and it’s got to be something like 25 years or so since I first read those words (in the HP Lovecraft Omnibus Vol 2, Dagon and other Macabre Tales, Grafton Books, 1985, p.423 ). So what about it?

It’s approximately 90 years since HP Lovecraft wrote, “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is the fear of the unknown.” (in the essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1926-7)), and it’s got to be something like 25 years or so since I first read those words (in the HP Lovecraft Omnibus Vol 2, Dagon and other Macabre Tales, Grafton Books, 1985, p.423 ). So what about it?

This kind of complexity is what makes history more interesting than it’s sometimes given credit for. The Scottish Enlightenment was a wonderful, positive, outward-looking movement, but it coexisted in Scotland with a joyless, moralising and oppressive Calvinist culture. Time and nostalgia have a way of homogenising peoples and cultures. The popular idea of ancient Rome is probably one of conquest, grandeur and decadence, but what is the popular idea, if there is one, of ‘an ancient Roman’? Someone, probably a man, probably from Italy, in a toga or armour; quite likely an emperor, a soldier or a gladiator, rather than say, a merchant, clerk or farmer. But even within this fairly narrow image, a complex figure like the emperor Elagabalus (who was Syrian, teenage, possibly transgender) defeats the obvious school textbook perceptions of ‘Roman-ness’ (as, perhaps, it did for the Romans themselves). Even in our own time, the fact that older generations from the 60s/70s to the present could lament the passing of times when ‘men were men & women were women’ etc is – to say the least – extremely disingenuous. Presumably what they mean is a time when non-‘manly’ men could be openly discriminated against and/or abused and women could be expected to be quiet and submissive.

This kind of complexity is what makes history more interesting than it’s sometimes given credit for. The Scottish Enlightenment was a wonderful, positive, outward-looking movement, but it coexisted in Scotland with a joyless, moralising and oppressive Calvinist culture. Time and nostalgia have a way of homogenising peoples and cultures. The popular idea of ancient Rome is probably one of conquest, grandeur and decadence, but what is the popular idea, if there is one, of ‘an ancient Roman’? Someone, probably a man, probably from Italy, in a toga or armour; quite likely an emperor, a soldier or a gladiator, rather than say, a merchant, clerk or farmer. But even within this fairly narrow image, a complex figure like the emperor Elagabalus (who was Syrian, teenage, possibly transgender) defeats the obvious school textbook perceptions of ‘Roman-ness’ (as, perhaps, it did for the Romans themselves). Even in our own time, the fact that older generations from the 60s/70s to the present could lament the passing of times when ‘men were men & women were women’ etc is – to say the least – extremely disingenuous. Presumably what they mean is a time when non-‘manly’ men could be openly discriminated against and/or abused and women could be expected to be quiet and submissive.

It’s an interesting point. The fleetingness with which you experience things has nothing to do with their power as memories. I have no idea what the first horror film I saw was, but I do know that a scene on some TV show where skinheads (or possibly a single skinhead) glued a man’s hands to the wall of a lift/elevator scared me as a child and stayed with me for a long time. Maybe that was because I used to see skinheads around on the streets (you had to watch the colour of the laces in their Doc Martens to see if they were ‘bad’ skinheads or not – though they were probably kids too, I now realise). I also know now (but didn’t then) that these were the

It’s an interesting point. The fleetingness with which you experience things has nothing to do with their power as memories. I have no idea what the first horror film I saw was, but I do know that a scene on some TV show where skinheads (or possibly a single skinhead) glued a man’s hands to the wall of a lift/elevator scared me as a child and stayed with me for a long time. Maybe that was because I used to see skinheads around on the streets (you had to watch the colour of the laces in their Doc Martens to see if they were ‘bad’ skinheads or not – though they were probably kids too, I now realise). I also know now (but didn’t then) that these were the

7. Bessie Smith – The Complete Recordings, Vol 1 (Columbia/Legacy)

7. Bessie Smith – The Complete Recordings, Vol 1 (Columbia/Legacy)

At first, Sweatshop feels more like one of Peter Bagge’s more lightweight, knockabout strips like Batboy or Studs Kirby, and compared to the brilliant Woman Rebel it is, but there’s more substance to the characters in Sweatshop than you’d think. This is perhaps because the situation (a group of ambitious young cartoonists working for a grouchy, reactionary, but famous old cartoonist to produce his well-known but trivial newspaper strip) is one close to the hearts of Bagge and his own team of artists. It’s funny and silly, but also well plotted and with some sharp observations about the world of cartooning as well as human relationships etc; a good book in fact.

At first, Sweatshop feels more like one of Peter Bagge’s more lightweight, knockabout strips like Batboy or Studs Kirby, and compared to the brilliant Woman Rebel it is, but there’s more substance to the characters in Sweatshop than you’d think. This is perhaps because the situation (a group of ambitious young cartoonists working for a grouchy, reactionary, but famous old cartoonist to produce his well-known but trivial newspaper strip) is one close to the hearts of Bagge and his own team of artists. It’s funny and silly, but also well plotted and with some sharp observations about the world of cartooning as well as human relationships etc; a good book in fact. The selection I have was collected by

The selection I have was collected by  I had already heard both of these great releases but when I saw that Mind Ripper were selling them on vinyl 7″s ridiculously inexpensively. Anthrophobia is a brilliant meeting of two very different musical personalities, with Godhole’s intensely emotive and strangely catchy powerviolence being distorted almost to the point of non-music by Crozier’s harsh noise; it’s bracing and not at all pretty, but it has a real impact and is worryingly addictive. The same is true of the Godhole EP, although it is relatively more disciplined insofar as it sounds like a band, rather than a catastrophic nightmare.

I had already heard both of these great releases but when I saw that Mind Ripper were selling them on vinyl 7″s ridiculously inexpensively. Anthrophobia is a brilliant meeting of two very different musical personalities, with Godhole’s intensely emotive and strangely catchy powerviolence being distorted almost to the point of non-music by Crozier’s harsh noise; it’s bracing and not at all pretty, but it has a real impact and is worryingly addictive. The same is true of the Godhole EP, although it is relatively more disciplined insofar as it sounds like a band, rather than a catastrophic nightmare. For 99% of the time, a complete contrast with the above (though the second half of Drones is surprisingly noisy and atonal), I was especially impressed by the forthcoming Cosmic Array album because I didn’t expect to like it at all. “Alt country/Americana”, ‘immersive and cinematic’ or not, is not really my thing* but in fact this album brings together a beautifully peculiar space-age melancholy that has (to me) hints of the Flaming Lips, Spacemen 3, My Little Airport and even the BMX Bandits and a sound that is a hybrid of UK indie and alt country (Fire Up The Sky is, strangely, almost shoegaze-alt country; actually, Moose’s XYZ was a great shoegaze/Americana album, so maybe not so strange?). Anyway; the songs are catchy and nice, Paul Battenbough and Abby Sohn are really good, expressive vocalists and it really is a big, widescreen cinematic sound as advertised; so put aside anti-country prejudices (if like me you have them) and give it a listen.

For 99% of the time, a complete contrast with the above (though the second half of Drones is surprisingly noisy and atonal), I was especially impressed by the forthcoming Cosmic Array album because I didn’t expect to like it at all. “Alt country/Americana”, ‘immersive and cinematic’ or not, is not really my thing* but in fact this album brings together a beautifully peculiar space-age melancholy that has (to me) hints of the Flaming Lips, Spacemen 3, My Little Airport and even the BMX Bandits and a sound that is a hybrid of UK indie and alt country (Fire Up The Sky is, strangely, almost shoegaze-alt country; actually, Moose’s XYZ was a great shoegaze/Americana album, so maybe not so strange?). Anyway; the songs are catchy and nice, Paul Battenbough and Abby Sohn are really good, expressive vocalists and it really is a big, widescreen cinematic sound as advertised; so put aside anti-country prejudices (if like me you have them) and give it a listen.

The third collaboration between Mike Patton and John Erika Kaada is, despite the ominous title, an extremely wide ranging and often light-toned (if moody, in the film-soundtrack sense) collection of dramatic and sometimes operatic (but not always melodramatic) pieces, ranging from the strangely Tom Waits-like Papillon to the Morricone-ish Black Albino. It’s a perfectly judged album, Mike Patton’s voice(s) interweaving with the orchestra to create individual pieces that are at the same time short and vast;too involving to be ‘background music’ it really does sound like an epic soundtrack in search of who knows what kind of film.

The third collaboration between Mike Patton and John Erika Kaada is, despite the ominous title, an extremely wide ranging and often light-toned (if moody, in the film-soundtrack sense) collection of dramatic and sometimes operatic (but not always melodramatic) pieces, ranging from the strangely Tom Waits-like Papillon to the Morricone-ish Black Albino. It’s a perfectly judged album, Mike Patton’s voice(s) interweaving with the orchestra to create individual pieces that are at the same time short and vast;too involving to be ‘background music’ it really does sound like an epic soundtrack in search of who knows what kind of film.