Then there was the close-up gulliver of this beaten-up starry veck, and the krovvy flowed beautiful red. It’s funny how the colours of the like real world only seem really real when you viddy them on the screen.

Now all the time I was watching this I was beginning to get very aware of like not feeling all that well… But I tried to forget this, concentrating on the next film which came on at once, my brothers, without any break at all. This time the film jumped right away on a young devotchka who was being given the old in-out by first one malchick then another then another then another, she creeching away very gromky through the speakers and very like pathetic and tragic music going on at the same time. This was real, very real…

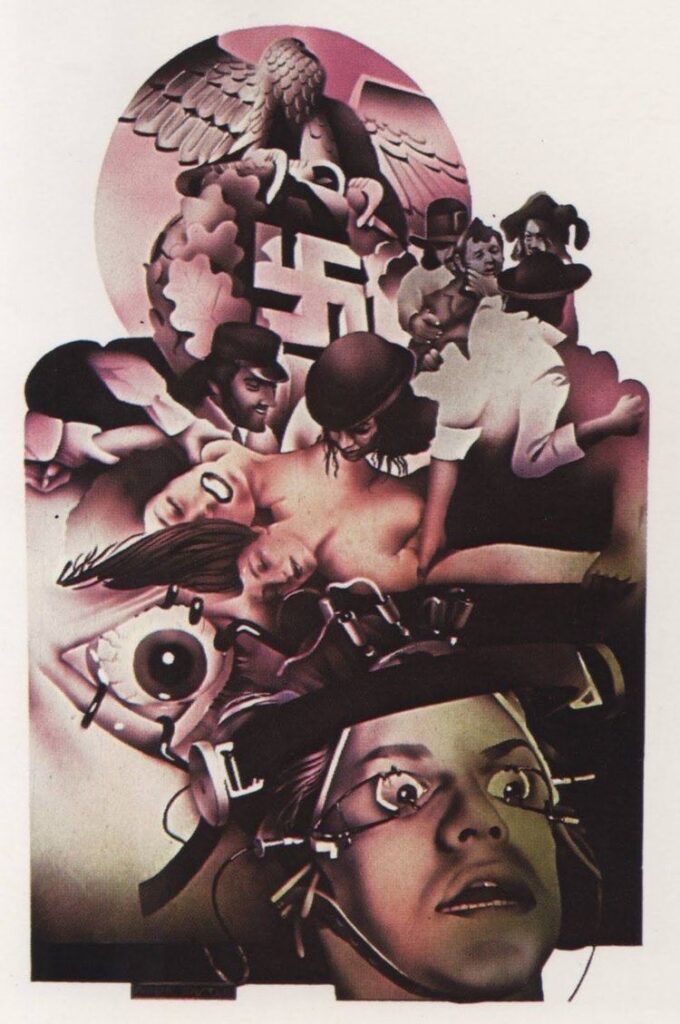

What it was now was the starry 1939-45 War again and it was a very blobby and liny and crackly film you could viddy had been made by the Germans. It opened with German eagles and the Nazi flag with that like crooked cross that all malchicks at school love to draw… Then you were allowed to viddy lewdies being shot against walls, officers giving the orders, and also horrible nagoy plots left lying in gutters, all like cages of bare ribs and white thin nogas. Then there were lewdies being dragged off creeching… Then I noticed, in all my pain and sickness, what music it was that like crackled and boomed on the sound-track, and it was Ludwig van, the last movement of the Fifth Symphony, and I creeched like bezoomny.” Anthony Burgess – A Clockwork Orange (1962), Penguin Modern Classics, p.70-78

In the twenty or so minutes before I had breakfast this morning, I looked at my phone and saw an armour-wearing police officer in Brussels attempt to assault a peaceful protester who was walking away from him and then saw the officer be knocked out by a less peaceful protester and left lying in the street, I saw a photograph of dozens of dead protesters in Iran in body bags, read a warning (or rumour?) that prisons in Iran are overwhelmed and so the authorities are releasing prisoners after injecting them with some kind of potassium-based agent which causes them to die within 48 hours of their release, I saw a really amazing 1984 live performance by John Cale that I’d never come across before, I saw a moronic incel-type video where a grown man was ‘educating’ young people (you’d assume men, but I think its intended audience was actually young girls) about the “Madonna-Whore complex,” though the presenter either didn’t realise or preferred not to acknowledge that Freud coined the term to describe a psychological disfunction and not to describe the natural state of humankind, I saw a funny old clip of the Young Ones, I saw an artist showing off a powerful and moving new painting, while explaining that their work was being stolen by AI companies, I read horrific details of abuse from the Epstein files, and heard so far unfounded claims about outlandishly horrific things that are imagined to be in the Epstein files, I saw/heard two outstanding actors being subjected to inadvertent racist abuse at the BAFTA awards, I saw old photos of atrocities in the Belgian Congo, a funny clip of Alan Partridge performing Kate Bush’s “Wuthering Heights”, I saw a short video about how Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights film is not like the book and that’s okay and another video about how Emerald Fennell’s Wuthering Heights whitewashes Heathcliff’s ethnicity and isn’t okay, I saw an alarming report about how AI will soon cause a global water shortage, I saw a great old interview clip with the artist Francis Bacon, an AI video purporting to be the sex-trafficker Ghislaine Maxwell enjoying her freedom, a real video of dead children in Gaza, I read details from the Epstein files of a successful plot to replace the British Prime Minister Theresa May, I saw old (but less old than you’d hope) postcards showing lynchings in the Southern United States with onlookers smiling at the camera while a corpse hangs in front of them, I saw a nice old clip of Slowdive performing “Catch the Breeze” in the early 90s, saw horrendous photos of a dead Iranian child killed by the regime there, read an explanation for the slow-of-thinking of why carpet bombing Iran wouldn’t actually help the Iranian people, saw a video of the latest Russian assault on Ukraine on the fourth anniversary of Russia’s invasion of that country, read an ‘explanation’ of why the whole Ukraine war is Fake News, saw a video about how the whole Royal Family is culpable for Prince Andrew’s predatory behaviour, another video about how Andrew’s arrest is an overreaction, footage from this year of a peaceful protester being shot by ICE agents in the USA, a German metal musician telling the crowd at Wacken that his band opposes racism, homophobia and right-wing extremism, heard a prominent extreme right wing politician in the UK stating that only his party can protect the UK from right-wing extremists, saw someone suggest that AI videos of fake sexual abuse might actually be helpful in reducing real sexual abuse, read an explanation of why AI altered videos of women and children is obviously harmful, saw some incredible art by artists who were complaining about censorship on social media sites, saw but didn’t take in lots of stuff about sports, watched a great old clip of Captain Beefheart and his Magic Band, scrolled past what seemed to be disinterested videos about how great AI is, but which were actually advertisements for AI. All of this was of all of course punctuated by many, many commercials that I didn’t take in enough to remember. It was real horrorshow.

Unlike Anthony Burgess’s Alex, who is being subjected to the fictional Ludovico Technique, a kind of aversion therapy, I was voluntarily exposing myself to this barrage of beauty and horror, and also unlike him I was free to stop it whenever I wanted to, which doesn’t of course prevent one’s brain from processing it – you can’t unsee a picture any more than you can un-ring a bell. A Clockwork Orange was written at the beginning of the 1960s, at the tail end of the 1950s paranoia about the way the media – meaning in those days mostly cinema, magazines and pop music – were fuelling juvenile delinquency. That paranoia exacerbated the generation gap which had already been made more prominent by the dividing line of World War Two. A reading of something like Hamlet suggests that there’s always been a generation gap, but it was in the 50s and 60s that it became a permanent, deliberate and indeed lucrative feature of western consumer culture.

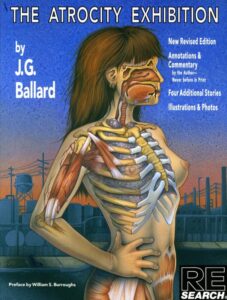

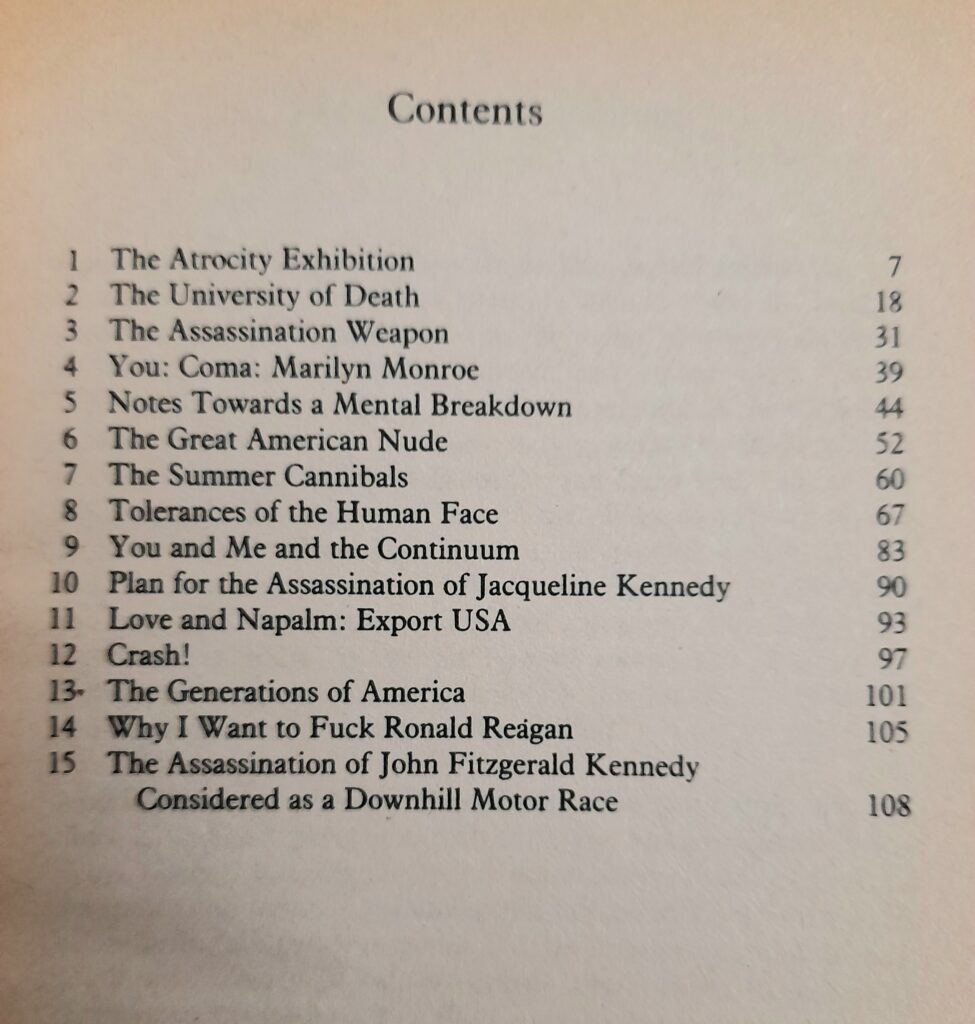

In 1970, the year that Stanley Kubrick’s film of A Clockwork Orange was released, one of Burgess’s peers, JG Ballard wrote The Atrocity Exhibition. Nothing about social media in 2026 would have surprised Ballard. If A Clockwork Orange was partly the product of society’s fears about rock ‘n’ roll, beatnik culture youth violence and communism, The Atrocity Exhibition was incubating during a period of widespread concern that a generation of young people was growing up seeing unfiltered images of the horrific events of the Vietnam War, intercut with commercials and entertainment features as they ate their breakfast every morning.

That was unprecedented – nearly everything is generally unprecedented it seems – and the fear was that, on the one hand these children would grow up inured to violence and horror and unable to differentiate between reality and entertainment, and on the other that their daily intake of atrocities was unconsciously being absorbed in a way that would eventually manifest itself as generational trauma. That was a natural concern at a time when it had only recently become acknowledged that World War One had left scars not just on those who survived it, but the whole of culture, and when the unprocessed horrors and consequences of World War Two were leading to a rise in neo-Nazism alongside a trivialisation of actual 1930s Nazism. Trauma begets trauma and trauma never ends, it seems, and that Vietnam experience has become the normal way of things in the social media age. The fact that some of the most powerful men in the world belong to that war-and-breakfast generation may or may not be relevant to where we are now.

So is my pre-breakfast bombardment a bad thing? Who knows, but it doesn’t seem like it could be a good thing. As Martin Amis wrote, when the (really quite tame) schlock horror movie Child’s Play 3 was being implicated in two different murder cases, “It’s nothing to boast about, but there is too much going on in my head for Chucky to gain much sway in there. Probably the worst that Chucky could do to me is to create an appetite to see more Chucky, or more things like Chucky.” He goes on to say that in the case of people already predisposed for whatever variety of reasons, to commit murder, “Chucky is unlikely to affect anything but the style of your subsequent atrocities.”* That seems right; the problem with seeing atrocities day in, day out isn’t that it wants to make normal people commit them. It is very depressing though. And the thought that my wearying daily experience might be – probably is – mirrored in the life of a deprived or abused child with nothing to look forward to but more deprivation and abuse is deeply unsettling.

*Martin Amis – The War Against Cliché (2001), p.17.

So why do it? Partly conditioning I suppose; in my case my morning look at social media not doom-scrolling, though I’m as guilty as anyone of periods of that. In A Clockwork Orange, the presence of Beethoven’s music – the only thing that Alex uncomplicatedly loves – appearing in the films that make up his therapy is an unfortunate coincidence, but in my case the nice things – the songs, the interview and comedy clips are there because they are the kind of things I consciously search for and the algorithm that wants to keep me there therefore supplies more of them. And it fills the gaps with whatever people I follow are talking about – Iran, Gaza, copyright infringement – and whatever its owners want to push at any given moment. Which right now, seems to be right-wing politics, salacious conspiracy theories and AI.

It feels like there should be some conclusions to be drawn from all this, but I don’t know what they are; maybe it’s too soon. But it seems deeply ironic that something very close to what was envisioned sixty years ago as an extreme and inhumane form of aversion therapy should be willingly engaged in by millions of people as part of their daily routine. When Anthony Burgess gave his sociopathic but jovial teenage narrator the slang term real horrorshow to denote enthusiastic approval he knew what he was doing.

of literature on outsider music, but for a highly readable and well-researched overview, Irwin Chusid’s

of literature on outsider music, but for a highly readable and well-researched overview, Irwin Chusid’s

Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so.

Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so. Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears.

Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears. every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation

every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation  isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism.

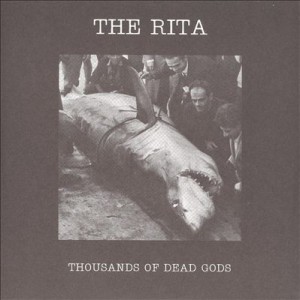

isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism. Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all.

Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all. This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.

This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.