I had already started writing this, but about half an hour ago the point I want to make was violently reinforced for me. I was waiting at the counter in a café, a radio was on in the background. A senior political figure was being interviewed – not a member of the current government but an elderly-sounding member of the House of Lords who was a veteran of the diplomatic service, I didn’t catch his name. Before I demonise him too much, I should point out that, even if he did represent the British government, he would have no real power over the situations he was invited on the air to discuss. In a way, that actually makes it worse, because it means he is in a position where he can openly speak his mind and presumably, this was his mind.

He was asked about two situations that are more similar than is often portrayed in the media, though one is significantly bloodier. That is, two invasions which are really attempted annexations or land-grabs by political leaders with ideological agendas. In the political discourse on the left you hear a lot about how differently the invasions of Ukraine and Palestine are being treated by the political and media establishments (and to a degree the British public), but although there is truth in that, to be fair to the interviewee, he barely differentiated between the two.

When asked about the latest meeting between the Presidents of the United States of America and Russia to discuss the fate of Ukraine – just writing that highlights the essential absurdity of it – the interviewee was reasonable, measured, but oddly wry. While he was clearly concerned about Ukraine and the plight of the Ukrainian people, the general tenor of his response was a kind of verbal shrug. The dryly amused ‘what-can-you-do-with-these-guys?’ tone characterises the way that many of the more serious figures in the British political and media spheres engage with the current administration of the USA and, to a lesser extent (because there’s no need to pretend that he’s an ally) with the government of Vladimir Putin. Moving on to Israel/Palestine/Gaza there was, similarly, some concern about the people currently being attacked, plus the expected bit of ‘what about Hamas?’ waffle, which I don’t think was disingenuous in this case, as it so often is. Because from the point of view of a career diplomat, there is a question about what happens with Hamas after the slaughter stops. It’s a problem that’s been made a much worse and much more unavoidable by Benjamin Netanyahu’s much-publicised funding of Hamas which essentially neutralised any chance of a moderate Palestinian government – but regardless of how they got there, it’s not a situation that will suddenly be resolved, whichever way (to put it coldly) the invasion of Gaza works out.

But when asked about Netanyahu himself – and it’s worth remembering what his reputation and status were before October 7th 2023 – and the current Israeli policy, that shrug returned; ‘what-can-you-do-with-these-guys?’ Well, it’s doubtful that a British diplomat, or even a member of the British government can do much to influence someone like Netanyahu – at least not while he has the backing of the US government – but one thing they can do and should do with any rogue politician from any country is to stop acting as if behaving in a consistent, predictable, true-to-character way is the same thing as behaving in an acceptable way. Given that the UN does have rules, guidelines and standards of conduct, acting as though the leaders of some of its nations are unfathomable forces of nature rather than political figures who make conscious policy choices is not helpful, either to the world or to the UN itself, which is only as effective as world leaders make it.

It would of course be nice if our political/media figures were bluntly critical of despots and would-be authoritarians – but if not, they could at least stop being indulgent towards them or nice about them. There are people who think that diplomacy is, by its nature damaging and wrong, but though it certainly can be, I believe in it, when used appropriately. It’s hard not to believe in it, if like me you grew up during the final phases of the Cold War. That decades of aggressive brinkmanship and paranoia should have ended peacefully with virtually no bloodshed (at least between the major players in the cold war) was a barely-credible relief at the time and, given the mental state and emotional temperature of world leaders in the 21st century, it now seems almost miraculous. That resolution really is a testament to the leaders, and particularly Mikhail Gorbachev, whose sober unflappability wasn’t shared by many politicians then, and doesn’t even seem to be a desired trait among the political class now. There are many times and many situations where sober, reflective diplomacy are desirable.

Conversely, when faced with the actions of hysterical, erratic, devious and capricious idiots or their cynical, opportunistic enablers and hangers-on, or coolly calculating monomaniacs, the kind of reasonable, statesmanlike professional on the radio this morning is at an immediate disadvantage. Acting according to the norms of your profession with people who have no respect for those norms is pointless at best. Even then, that doesn’t negate the whole profession of diplomacy; when meeting with powerful, impetuous morons, being calm and professional is a given and, for many reasons it’s the right thing to do. But to go further than that – to act like the terrified child who wants to appease the bully, or the substitute teacher who wants the scary kids to think they are cool – is a mistake that politicians, unless they happen to be in the final twilight of their careers, will live to regret.

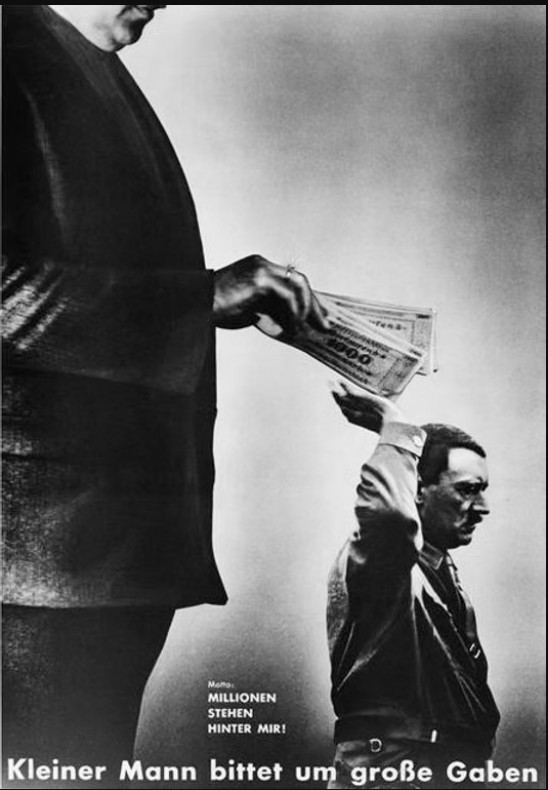

Wherever there are tyrants, authoritarians and powerful reactionaries, there is never any shortage of people willing – even against their own interests – to defend and promote them. But we are currently at a strange point in history where these people are so brazen and shamelessly open about their own actions that media commentators and politicians – occasionally with no special vested interest (but often with a financial one) – who do see the shame in those actions are willing to make claims on the behalf of their idols which go beyond any statement made by the perpetrators themselves. I would expect this to be a right-wing problem, because I’m a prejudiced left-winger, but it seems to be more of an ideological problem than one that is specific to either end of the spectrum.

And so, even though on the eve of the invasion of Ukraine, Vladimir Putin himself gave a long speech on Russian TV, where he ranted at length about historical grievances, denied Ukraine’s right to exist at all and talked about restoring the old Russian Empire, never once mentioning NATO, British commentators on both the left and right have repeatedly attempted to justify Putin’s actions with reference to the perceived threat to Russia’s borders posed by NATO expansionism and so forth. It doesn’t seem that Putin has asked them to legitimise his actions – he doesn’t seem to think his actions need justifying at all, beyond the simple fact that he thinks Russia should own Ukraine – so why embarrass yourself by making claims on his behalf?

Similarly, members of the Israeli government have been blunt about their desire to remove the Palestinian people from Gaza one way or another. Those of us with memories going back a few months may even remember discussion, involving the US government, about turning the area into a resort. There are photos online of members of the IDF standing in ruins holding the banners of real estate companies, there are videos shared by IDF fighters where they laugh as they rake through the underwear drawers of Palestinian women in their deserted houses, where they joke about using children for target practice. As the Israeli historian Ilan Pappé has discussed, it’s not like these kinds of debates on what to do with Palestine are new or unusual. So why would any western politician or media spokesperson feel the need to frame the situation as a war between two equal states, or talk endlessly about the hostages that the Israeli government seems not to care about?

In lieu of holding Netanyahu’s administration to the standards expected of every other member of the UN, we are instead constantly asked what about Hamas? Well, no doubt they have their own gloating social media presence, glorifying their inhuman acts, but they aren’t an everyday part of normal, Western social media and however much the Israeli government likes to frame all criticism of themselves as antisemitic Hamas propaganda, I haven’t so far seen a single mainstream politician online or on TV criticise Israeli policy without also condemning Hamas and calling for the freeing of those Israeli hostages. That those hostages are important and should be prioritised should go without saying, just as the fact that almost everyone living in a Western democracy is fundamentally opposed to a repressive theocratic organisation like Hamas should go without saying; and yet it has to be stated again and again because of the way the events – in reality it can barely be categorised as a conflict, let alone a war – are being presented.

So, yes, there is definitely a time for diplomacy – it’s both necessary and desirable when negotiating the different cultures, belief systems, nationalities and identities that make up the modern world. And while it would be nice – a relief even – to hear a senior British politician not just commenting on or blandly ‘condemning’ the words or actions of any rogue regime, whether our supposed allies or not, nor just or urging them to change their ways – but launching a scathing tirade against them, taking legal action in international courts and cutting all unnecessary ties with them, nobody can realistically expect that, It’s just not how politics work. But, as our successive governments have managed to coexist for decades alongside ideologically opposed countries like China or North Korea without the constant threat of war and without feeling the need to openly pander to and flatter their leaders, then it shouldn’t be too much to ask that they do the same with governments whose values are not supposed to be so far removed from our own.

Speaking as a citizen of the UK, if the core values of our country really are what we say they are – democracy, tolerance, compassion and all that – then at some point, coming up against the opposite, diplomacy should only go so far.

————————————————————————–

Postscript: on the day I started writing the final version of this, I heard that radio interview. This morning, as I finished it I saw three news stories that all made this mild call for bluntness seem worse than ineffectual: in one, the Israeli government had targeted and wiped out an entire Al Jazeera news crew. Typically, the UK news talks about ‘collateral damage,’ but IDF spokespeople have talked proudly about removing “Hamas terrorist” Anas al-Sharif, who neither they nor anybody else believes was a Hamas terrorist, because he demonstrably wasn’t.

In the USA, the President, while deflecting questions (again) about the files relating to a dead paedophile that was once a friend of his, is talking openly about forcibly removing city administrations to ‘re-establish law and order’ in areas which seemed to have had no special law and order issues until he created or declared them.

Finally, I was watching footage of an old blind man, a woman in her eighties and an elderly military veteran being arrested by the police for holding placards at a peaceful protest while, elsewhere in the UK the police impassively watched a mob of people screaming racist abuse at a hotel where refugees from war zones are being housed, and stood casually by as the leader of an admittedly moribund political party danced around and made Nazi salutes. There is no single correct response to these events, but empty diplomacy from the country’s leaders has nothing to offer in any of them.