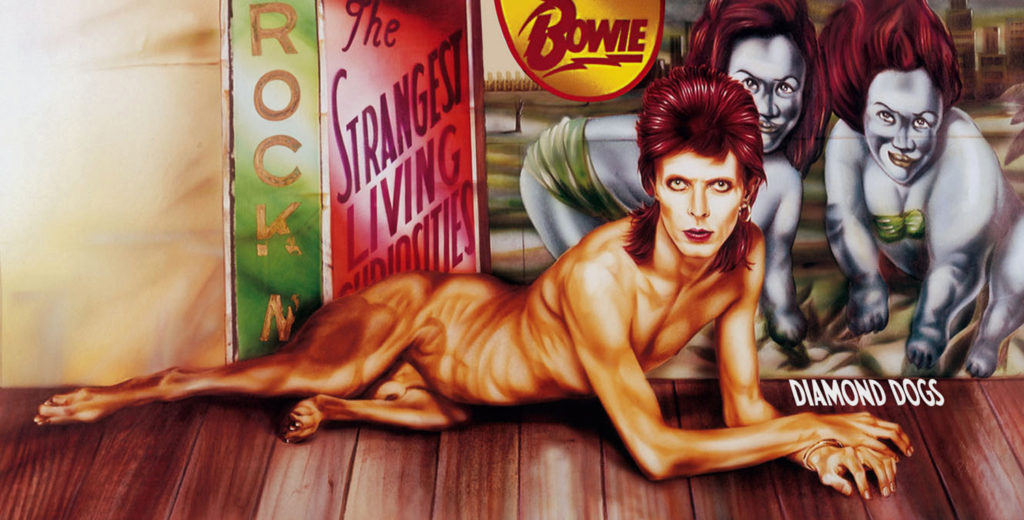

I don’t often post book reviews here, but I was lucky enough to be sent review copies of the two newest additions to Bloomsbury’s always-interesting 331⁄3 series of books, David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs by Glenn Hendler (hopefully the spelling of his name will be consistent on the cover of the non-advance edition) and D’Angelo’s Voodoo by Faith A. Pennick, which I’ll cover in a different post.

Hendler’s book was of immediate interest; I’ve been listening to David Bowie’s Diamond Dogs (1974) for literally (though not continuously) half of my life. When I first started this blog, names for it that I rejected included ‘The Glass Asylum’ (from the song Big Brother) and ‘Crossroads and Hamburgers’ (actually based on a mishearing of a line in perhaps-best-ever-Bowie-song (or group of songs), Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (reprise) which is really ‘the crossroads of hamburgers and boys’, arguably a better name for a website, but perhaps overly misleading. The Glass Asylum already exists and is anyway not especially relevant. But I’ll name this site properly one day).

For years, Diamond Dogs was my favourite Bowie album, only pushed into second or third place (it changes quite often; currently #1 is Station to Station and #2 is Young Americans) because I listened to it so much that it had become hard to listen to without skipping bits.

But despite listening to it to the point where I felt like I knew every second of the album, and reading a lot about Bowie over the years (though not the lyrics apparently – I presume I just thought I knew them), Glenn Hendler’s little (150 page) book taught me a lot that I didn’t know and hadn’t considered – and, even better – sent me back to the album with fresh ears, and made me fall in love with it all over again.

As a semi-professional music journalist myself (Hendler, incidentally, isn’t one; he’s a Professor of English, though he writes on a variety of cultural & political topics) I’m very aware that there are many people who believe that music writers should focus solely on the music at hand and leave themselves out of it. This is, thankfully, not how the 331⁄3 series works, and in fact none of my own favourite music writers – Charles Shaar Murray, Jon Savage, Caitlin Moran, Lester Bangs etc etc – write from any kind of neutral position. And really, anything about music beyond the biographical and technical information is subjective anyway, so better to be in the hands of someone whose writing engages you. For me, the test of good music journalism (not relevant here, but will be for the Voodoo review) is whether the writer can make you enjoy reading about music you don’t already know, or maybe don’t even like – something which all of the aforementioned writers do.

331⁄3 books always begin with something about the writer’s history with the music that they are talking about – and it’s surprising the difference this makes to a book. For me, reading the opening chapter of Mike McGonigal’s My Bloody Valentine’s Loveless (Loveless came out when I was at high school and was very much a fan of the scene that had grown up in the long gaps between MBV’s releases; Ride, Lush, Slowdive, Curve etc etc etc) was such a strange experience – he describes encountering the band’s music in what comes across very much as a grunge, ‘alt-rock’ milieu – that, although I liked the book very much, it felt so far removed from how I saw the band that it was oddly dislocating, like it would be to read a sentence that began “Wings frontman Paul McCartney” or, more pertinently to this article, “David Bowie, vocalist of Tin Machine.”

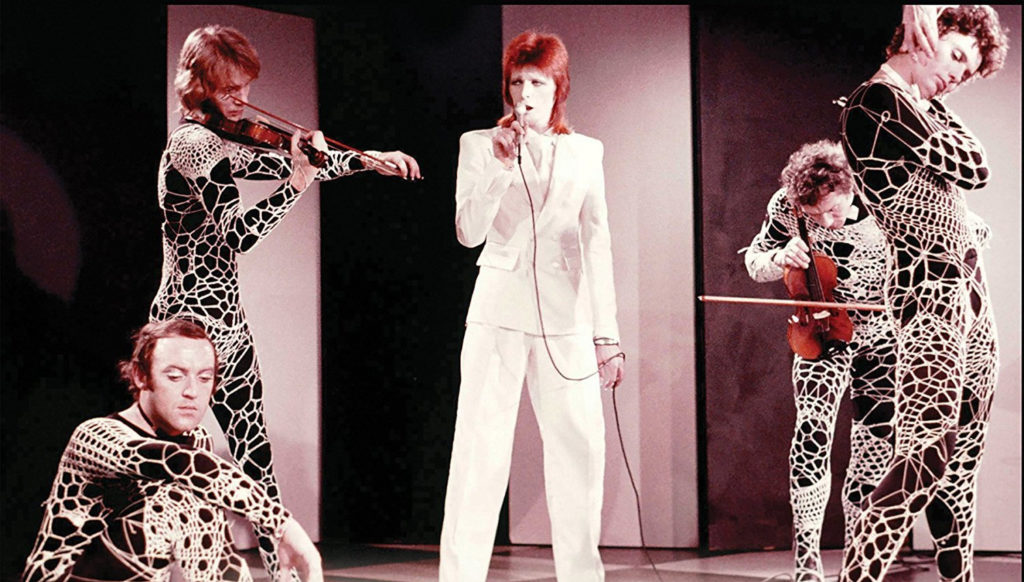

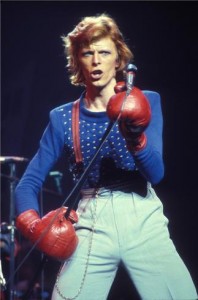

Anyway; in this case, the author’s relationship with his subject stretches all the way back to the his first real encounter with the music – and strangeness – of Bowie, when as a 12 year old, he saw The 1980 Floor Show on NBC’s Midnight Special, filmed in 1973, which acted as a kind of fanfare for the as-yet-unreleased Diamond Dogs. This setting is important, because anyone coming to Bowie now has grown up with all of his incarnations – and the fact that he had various different personae – as background. I first knew him as the barely-weird-at-all Bowie of Let’s Dance, a pop star who was not noticeably stranger or even (stylistically/musically at least) obviously older-looking than the other acts in the charts at the time (also in the top ten during Let’s Dance’s reign at number one were the Eurythmics (Sweet Dreams (are Made of This)), Bonnie Tyler (Total Eclipse of the Heart) and Duran Duran (Is There Something I should know). The fact (not in itself so unusual in the UK) that Bowie had an earlier existence as some kind of glam rock alien of indeterminate gender was almost invariably commented upon by DJs and TV presenters in the 80s and that is a very different thing from becoming aware of him when he was a glam rock alien of indeterminate gender, especially since – in the USA at least – he was yet to really break and in ’74 was a cult figure with a surprisingly high profile, rather than one of the major stars of the previous two years.

In his book, rather than making a chronological, song-by-song examination of the album (though he does dissect every song at some point), Hendler examines the array of different inspirations (musical, literary, cultural, political, technical) that informed the writing and recording of the album, as well as looking at where it lies in relation to his work up to that point. Those inspirations; Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four (Bowie’s original intention was to write a musical based on the book, but after that was vetoed by Sonia Orwell he incorporated the material he’d written into Diamond Dogs), Andy Warhol and the superstars of his Factory, some of whom were then in the UK production of his play Pork, the gay subculture of London and the post-apocalyptic gay subculture of William Burroughs’s novels, Burroughs & Brion Gysin’s ‘cut-up’ technique, Josephine Baker, A Clockwork Orange, the soul and funk that was to take centre stage on Young Americans, the Rolling Stones, the post-industrial decay and unrest of Britain in the mid-70s – are all audible to varying degrees on Diamond Dogs, a kind of linguistic stratigraphy* that mirrors the album’s layers of sounds and instruments and makes it both aurally and figuratively one of Bowie’s most richly dense albums.

*thankfully, Glenn Hendler never writes as pretentiously as this

When reading the book, two phrases other writers wrote about the Diamond Dogs era came to mind, which I think reinforce Hendler’s own conclusions about the album;

it […] single-handedly brought the glam rock era to a close. After Diamond Dogs there was nothing more to do, no way forward which would not result in self-parody or crass repetition” David Buckley – The Complete Guide To The Music of David Bowie*, Omnibus Press, 1996, p.37

*incidentally, a intriguing detail reported by Buckley but sadly not mentioned in Hendler’s book is that the territory of ‘Halloween Jack’ (the only named member of the Diamond Dogs) who ‘lives on top of Manhattan Chase’ was inspired by stories told by Bowie father (who at one point worked for Barnardo’s) of homeless children living on the rooftops in London.

And, even more to the point:

The last time I’d seen him [Bowie] had been the last day of 1973, and he’d been drunk and snooty and vaguely unpleasant, a game player supreme, a robot amuck and careening into people with a grin, not caring because after all they were only robots too; can trash be expected to care about the welfare of other trash?

Since then there’d been Diamond Dogs, the final nightmare of glitter apocalypse Charles Shaar Murray, ‘David Bowie: Who was that (un)masked man?’(1977) in Shots From The Hip, Penguin books, 1991, p.228

This sense of Diamond Dogs’ apocalyptic extremism is addressed throughout Hendler’s book; the record may not be a concept album in any clear, narrative sense (indeed, the Diamond Dogs, seemingly some kind of gang, are introduced early on but only mentioned once thereafter), but its fractured, non-linear progression and its musical maximalism (should be a thing if it isn’t) actually imbues the album with a far stronger overall identity than Ziggy Stardust or Aladdin Sane had before it. In fact it works more like a kind of collage than a conventional story. related to this, an important point that the author brings up early on concerns the role of the Burroughs/Gysin cut up technique. Although this is often used to explain (or rather, not explain) the more lyrically opaque moments in Bowie’s 70s work, Hendler stresses that this was a creative tool rather than a kind of random lyric generator. As with the use of Eno’s Oblique Strategies cards on Low a few years later, the cut up was used as a way of stimulating the imagination, not bypassing it. The lyrics to songs like Sweet Thing clearly benefit from the use of randomised elements, but these were then used to create lyrics which have an internal sense but which crucially also scan and rhyme when needed, something that would be fairly unlikely in a purely random process. The result is something like the experimental fiction that JG Ballard had pioneered earlier in the decade (most famously in The Atrocity Exhibition) which come across as sometimes-gnomic bulletins from the unconscious, filtered through a harsh, post-industrial geography, but never as random gibberish. What Hendler draws attention to (that I had never consciously noticed in all my years of listening) is the strangely dislocated perspectives of the album’s songs, where the relationship between the narrator/subject/listener are rarely clear-cut and often change within the course of a single song.

The most obvious example is in one of the book’s best parts, the exploration of Sweet Thing/Candidate/Sweet Thing (reprise) (the crossroads and hamburgers song). Although, lyrically, the song’s focus is all over the place, it never feels disjointed, and until reading about it, I’d never really considered how ambiguous it all is. Although seen through a kind of futuristic lens, thanks to the album’s loose concept (established by the album’s sinister and slightly silly intro, Future Legend), when I listen to it now, it feels very much like a condensed/compressed 70s version of Hubert Selby Jr’s notorious Last Exit To Brooklyn (1964) with its shifting viewpoints and voices and its pitiless depiction of what was – for all the novel’s controversy – the normal life for many people in the underclass of any big city. Like Selby, Bowie doesn’t help the audience by indicating who is speaking or when but places us in the centre of the action (essentially violent gangs and male prostitutes), making the listener in fact, (at times) the ‘sweet thing’ of the title (though at other times Bowie adopts that role too) not that that had ever occurred to me before. It’s a mixture of menace, sleaze and impending violence, the ‘glam’ sheen of glam rock rendering it all at once romantic and dangerous – and full of unexpected details. I had obviously always heard the line ‘Someone scrawled on the wall “I smell the blood of Les Tricoteuses”’ but I hadn’t bothered to find out what it was he said or what ‘Les Tricoteuses’ were (the old ladies who reportedly/supposedly knitted at the foot of the guillotine during the Reign of Terror that followed the French Revolution, it turns out) and therefore didn’t pick up on the way the percussion becomes the military marching snare drum. Bowie was always about theatre, but this song absorbs the theatrical elements so seamlessly into its overall structure that drama/melodrama, sincerity/artifice, truth/deceit. seduction/threat become one vivid and affecting whole. I would say the song is bigger than the sum of its parts, but there are so many parts, going in (and coming from) so many different directions that I don’t think that’s true – but it somehow holds together as a song or suite of songs; almost a kind of microcosm of the album itself.

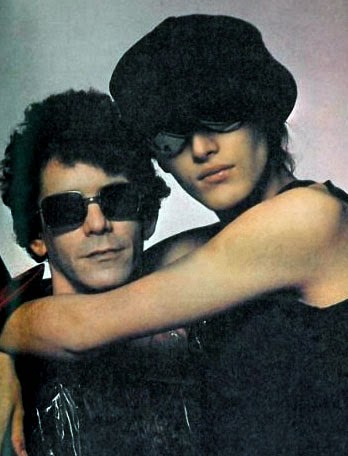

Elsewhere, my other favourite song, We Are The Dead (directly inspired by Nineteen Eighty-Four) is dissected brilliantly, highlighting the way (again, I hadn’t noticed) that Bowie absorbs the key ideas of the novel into his own framework; this is one of the few songs aside from the title track that mentions the Diamond Dogs and, without being jarring (or at least no more than intended) sets the originally very 1940s characters of Winston Smith and Julia (not that they are named) and his timeless themes of power, sex (and the relationship between the two) and totalitarianism into the 70s post-apocalyptic dystopia that owes more to Burroughs and the street-life milieu of Lou Reed’s lyrics than it does to Orwell himself. Like the use of cut-up techniques to stimulate his own imagination, Bowie’s absorption of these disparate elements created something new and powerful that concentrated Bowie’s interests and obsessions as well as holding up a distorting mirror to the times in which it was created.

But this has gone on long enough and, rather than rewriting or paraphrasing Hendler’s book – one of the best books on Bowie I’ve read – I’ll go and read it again while listening to Diamond Dogs.

I am (as I think most people probably are!) quite fussy about death metal, but without being retro in any kind of self-conscious way, De Profundis make music that would sit happily in the late 80s/early 90s death metal scene. The Blinding Light of Faith is an album that can hold its own in the company of any of the big names of death metal; superb, intelligent musicianship and songwriting – it’s a seriously impressive album.

I am (as I think most people probably are!) quite fussy about death metal, but without being retro in any kind of self-conscious way, De Profundis make music that would sit happily in the late 80s/early 90s death metal scene. The Blinding Light of Faith is an album that can hold its own in the company of any of the big names of death metal; superb, intelligent musicianship and songwriting – it’s a seriously impressive album. 80s veteran(s) Lizzy Borden (both a singer and a band) seem always to suffer from being mis-pigeonholed, whether as a glam band (he/they did have the image), Twisted Sister clones (ditto), or some kind of Alice Cooper-esque horror-metal act (partly the name, partly the image innit), but if you listen back to the best of the band’s 80s work, especially Love You To Pieces, they were really a classic metal band, more Iron Maiden-meets-W.A.S.P. than Motley Crue. On the new album Lizzy himself takes centre stage, singing better than he ever has – no mean feat – and playing all the guitars on what is a very song-based album. It’s not very heavy – more a kind of homage to bands like Cheap Trick and Queen than the early 80s Lizzy Borden sound. But it’s really good if you like that kind of thing, and it’s great to hear Lizzy really going for it after a couple of slightly patchy, compromised-sounding, ‘not bad’ records.

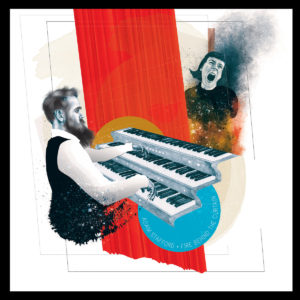

80s veteran(s) Lizzy Borden (both a singer and a band) seem always to suffer from being mis-pigeonholed, whether as a glam band (he/they did have the image), Twisted Sister clones (ditto), or some kind of Alice Cooper-esque horror-metal act (partly the name, partly the image innit), but if you listen back to the best of the band’s 80s work, especially Love You To Pieces, they were really a classic metal band, more Iron Maiden-meets-W.A.S.P. than Motley Crue. On the new album Lizzy himself takes centre stage, singing better than he ever has – no mean feat – and playing all the guitars on what is a very song-based album. It’s not very heavy – more a kind of homage to bands like Cheap Trick and Queen than the early 80s Lizzy Borden sound. But it’s really good if you like that kind of thing, and it’s great to hear Lizzy really going for it after a couple of slightly patchy, compromised-sounding, ‘not bad’ records. Away from metal, this is a really interesting, good album if you like – well, what? “Film soundtrack music” isn’t really a genre, is it, but that’s what Fire Behind The Curtain makes me think of. I’ve seen it described as neoclassical and minimalist too, but neither of those feels quite right to me. It’s a beautifully cohesive-yet-eclectic collection of mostly-instrumental pieces vary from haunting and bleakly forbidding atmospheres to warm and embracing melodies.

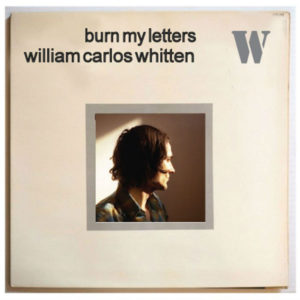

Away from metal, this is a really interesting, good album if you like – well, what? “Film soundtrack music” isn’t really a genre, is it, but that’s what Fire Behind The Curtain makes me think of. I’ve seen it described as neoclassical and minimalist too, but neither of those feels quite right to me. It’s a beautifully cohesive-yet-eclectic collection of mostly-instrumental pieces vary from haunting and bleakly forbidding atmospheres to warm and embracing melodies. I can’t really write an awful lot about this album from the always-dependable I Heart Noise label, as I’ve only just started listening to it really; but so far I love it. It makes me think of Lou Reed, or Alan Vega covering John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band album; sparse, forlorn, world-weary and a little bit sleazy.

I can’t really write an awful lot about this album from the always-dependable I Heart Noise label, as I’ve only just started listening to it really; but so far I love it. It makes me think of Lou Reed, or Alan Vega covering John Lennon’s Plastic Ono Band album; sparse, forlorn, world-weary and a little bit sleazy.

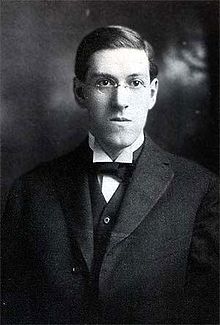

It’s approximately 90 years since HP Lovecraft wrote, “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is the fear of the unknown.” (in the essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1926-7)), and it’s got to be something like 25 years or so since I first read those words (in the HP Lovecraft Omnibus Vol 2, Dagon and other Macabre Tales, Grafton Books, 1985, p.423 ). So what about it?

It’s approximately 90 years since HP Lovecraft wrote, “The oldest and strongest emotion of mankind is fear, and the oldest and strongest kind of fear is the fear of the unknown.” (in the essay Supernatural Horror in Literature (1926-7)), and it’s got to be something like 25 years or so since I first read those words (in the HP Lovecraft Omnibus Vol 2, Dagon and other Macabre Tales, Grafton Books, 1985, p.423 ). So what about it?

This kind of complexity is what makes history more interesting than it’s sometimes given credit for. The Scottish Enlightenment was a wonderful, positive, outward-looking movement, but it coexisted in Scotland with a joyless, moralising and oppressive Calvinist culture. Time and nostalgia have a way of homogenising peoples and cultures. The popular idea of ancient Rome is probably one of conquest, grandeur and decadence, but what is the popular idea, if there is one, of ‘an ancient Roman’? Someone, probably a man, probably from Italy, in a toga or armour; quite likely an emperor, a soldier or a gladiator, rather than say, a merchant, clerk or farmer. But even within this fairly narrow image, a complex figure like the emperor Elagabalus (who was Syrian, teenage, possibly transgender) defeats the obvious school textbook perceptions of ‘Roman-ness’ (as, perhaps, it did for the Romans themselves). Even in our own time, the fact that older generations from the 60s/70s to the present could lament the passing of times when ‘men were men & women were women’ etc is – to say the least – extremely disingenuous. Presumably what they mean is a time when non-‘manly’ men could be openly discriminated against and/or abused and women could be expected to be quiet and submissive.

This kind of complexity is what makes history more interesting than it’s sometimes given credit for. The Scottish Enlightenment was a wonderful, positive, outward-looking movement, but it coexisted in Scotland with a joyless, moralising and oppressive Calvinist culture. Time and nostalgia have a way of homogenising peoples and cultures. The popular idea of ancient Rome is probably one of conquest, grandeur and decadence, but what is the popular idea, if there is one, of ‘an ancient Roman’? Someone, probably a man, probably from Italy, in a toga or armour; quite likely an emperor, a soldier or a gladiator, rather than say, a merchant, clerk or farmer. But even within this fairly narrow image, a complex figure like the emperor Elagabalus (who was Syrian, teenage, possibly transgender) defeats the obvious school textbook perceptions of ‘Roman-ness’ (as, perhaps, it did for the Romans themselves). Even in our own time, the fact that older generations from the 60s/70s to the present could lament the passing of times when ‘men were men & women were women’ etc is – to say the least – extremely disingenuous. Presumably what they mean is a time when non-‘manly’ men could be openly discriminated against and/or abused and women could be expected to be quiet and submissive.

It’s an interesting point. The fleetingness with which you experience things has nothing to do with their power as memories. I have no idea what the first horror film I saw was, but I do know that a scene on some TV show where skinheads (or possibly a single skinhead) glued a man’s hands to the wall of a lift/elevator scared me as a child and stayed with me for a long time. Maybe that was because I used to see skinheads around on the streets (you had to watch the colour of the laces in their Doc Martens to see if they were ‘bad’ skinheads or not – though they were probably kids too, I now realise). I also know now (but didn’t then) that these were the

It’s an interesting point. The fleetingness with which you experience things has nothing to do with their power as memories. I have no idea what the first horror film I saw was, but I do know that a scene on some TV show where skinheads (or possibly a single skinhead) glued a man’s hands to the wall of a lift/elevator scared me as a child and stayed with me for a long time. Maybe that was because I used to see skinheads around on the streets (you had to watch the colour of the laces in their Doc Martens to see if they were ‘bad’ skinheads or not – though they were probably kids too, I now realise). I also know now (but didn’t then) that these were the

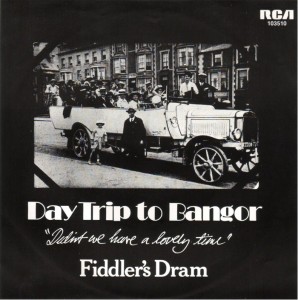

But what did I hear first? Who knows? I remember my mother playing guitar and singing, but ridiculously, the actual song that stands out as the first identifiable thing I remember, can name and even know some of the words to is neither parent music, nor standard chart fare; it’s Day Trip To Bangor by Fiddler’s Dram, which sets the date I began to really absorb music at around 1979; which makes sense, as until around that point I had hearing problems. As earliest memories go it could be more significant – I didn’t like it (or dislike it, as far as I remember), I can’t picture the band, it isn’t the soundtrack to a specific event. I just remember it, like I remember Crown Court and Pebble Mill At One being on TV in the afternoon if I was ill at home instead of being at school. It’s also to the end of the 70s that the first 7” single actually owned by me belongs and it’s also a typical-of-its-era novelty record, by the already long-in-the-tooth comedy group The Barron Knights – ‘A Taste of Aggro’. It’s the kind of random thing that little kids like; it features parodies of ‘The Smurf Song’ and Boney M’s ‘Rivers of Babylon’ (‘there’s a dentist in Birmingham…’ ). In my first year or two at primary school I also remember liking at least one Adam and the Ants song, I liked Toyah and Hazel O’Connor when they were on TV, I liked the disco version of the Star Wars theme and ‘Cars’ by Gary Numan. Other music-related memories of the time are pretty vague; I remember older kids who were punks and (more scary to small-child me) skinheads, but I don’t think I ever heard their music at the time.

But what did I hear first? Who knows? I remember my mother playing guitar and singing, but ridiculously, the actual song that stands out as the first identifiable thing I remember, can name and even know some of the words to is neither parent music, nor standard chart fare; it’s Day Trip To Bangor by Fiddler’s Dram, which sets the date I began to really absorb music at around 1979; which makes sense, as until around that point I had hearing problems. As earliest memories go it could be more significant – I didn’t like it (or dislike it, as far as I remember), I can’t picture the band, it isn’t the soundtrack to a specific event. I just remember it, like I remember Crown Court and Pebble Mill At One being on TV in the afternoon if I was ill at home instead of being at school. It’s also to the end of the 70s that the first 7” single actually owned by me belongs and it’s also a typical-of-its-era novelty record, by the already long-in-the-tooth comedy group The Barron Knights – ‘A Taste of Aggro’. It’s the kind of random thing that little kids like; it features parodies of ‘The Smurf Song’ and Boney M’s ‘Rivers of Babylon’ (‘there’s a dentist in Birmingham…’ ). In my first year or two at primary school I also remember liking at least one Adam and the Ants song, I liked Toyah and Hazel O’Connor when they were on TV, I liked the disco version of the Star Wars theme and ‘Cars’ by Gary Numan. Other music-related memories of the time are pretty vague; I remember older kids who were punks and (more scary to small-child me) skinheads, but I don’t think I ever heard their music at the time.

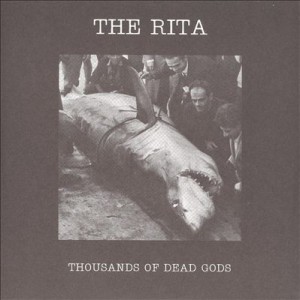

Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so.

Thousands of Dead Gods (2006) by The Rita many times without ever getting used to it. This makes the noise endlessly surprising, alienating or boring, depending on one’s mood. The sense of noise as abstract is reinforced by its context-lessness; typically the artwork for a Merzbow album is as enigmatic and unrevealing as the album within, and occasionally every bit as flatly un-evocative (not a criticism!) as the Merzbow sound itself. Cultural identifiers in pure noise are also minimalist in the extreme; the race, nationality or gender of noise artists tends to be known only insofar as the artist wishes it to be so. Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears.

Back in the 80s, this kind of music had an outsider/snob appeal even within the metal genre. 80s metal (on the whole) strove for clarity and precision; Carcass (emerging from an anarcho-crust/punk background) pushed the boundaries of musical extremity and taste (using the notorious collages of medical photos for their artwork, rather than relatively cuddly horror mascots like Iron Maiden’s Eddie) beyond what the standard fan of Iron Maiden, W.A.S.P., Metallica or even Slayer might find acceptable. To say that death metal is relatively lighthearted is slightly misleading – Carcass’ early music was informed by a radical vegetarian disgust with all things meat-based in quite a serious way – but as a subgenre of a popular youth-focussed music it lacks the gravitas of the kind of music which made the late 70s a darker place to have ears. every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation

every bit as evocative of the 1970s as glam or disco, but the way it embodies its era, its brutalist architecture and grey/brown/beige ambience, combats any possible sense of nostalgia. Although it’s easy to say why it’s interesting, liking Throbbing Gristle (as many have done and continue to do) is much harder to explain. The appeal of TG; in effect the appeal of being made to feel uneasy or disgusted, is an odd way to be entertained. On the surface you could say the same about the horror genre in cinema and literature, but Throbbing Gristle’s effect is utterly different from straightforward horror-as-entertainment, feeling (to me anyway) more analogous to the JG Ballard of The Atrocity Exhibition or Crash than to Stephen King, perhaps because like Ballard, TG’s work had more to do with documenting than it did with entertaining. Although there was undoubtedly an element of confrontation in TGs music (especially in a live setting), as with pure noise, confrontation  isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism.

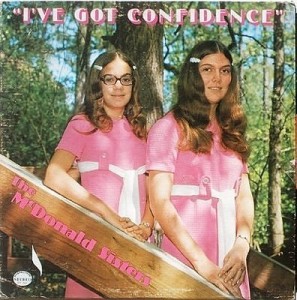

isn’t the focal point that it becomes in the power electronics of groups like Whitehouse and Sutcliffe Jügend who (to some extent) followed on from the early British industrial scene. There is also a more straightforwardly ‘horror noise’ sub-subgenre including bands like Abruptum and the aforementioned Gnaw Their Tongues, whose aim seems to be to engender (with, it must be said, varying degrees of success) extreme anxiety in the listener; significantly different from the almost abstract quality of pure (if harsh) noise artists like Merzbow, easier to understand, but also easier to dismiss as sensationalism. Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all.

Across all of the arts there are ‘so bad it’s good’ works that appeal on the ironic level of kitsch. These are completely subjective and therefore a bit of a minefield; at what point does listening to something that you personally think is so awful that it’s funny become just listening to it; and is there any difference anyway? Did my teenage self and friends have a different experience listening to an old Shakin’ Stevens tape ‘for a laugh’ than “Shaky”’s actual fans did or do? Well, yes, presumably; they probably don’t laugh as much. Still; it’s all ‘listening with pleasure’ and not only is it subjective, but it’s all about timing. The awfulness of music is as much about the zeitgeist as the popularity of music is; hard to imagine now, but there was a time in the late 80s when listening to Abba (or The Carpenters for that matter) could be enjoyed as revelling in tacky 70s awfulness; but since the early 90s they have been revered by the once-embarrassed media as a great band after all. This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.

This category takes it for granted that unhappiness is a form of unpleasantness that is most often avoided; which may not be strictly true – or obviously isn’t, given the endless popularity of tragedies, murder mysteries etc. Still, it’s a basic human truth (I hope) that most people would rather be happy than sad. Most of the time that is; historically, music was most often written for occasions; sad music was required for a funeral, just as weddings demanded happy music. Tudor and baroque music often had mythological, narrative or literary inspiration which dictated the mood of the works. For a court composer to make a cheerful-sounding funeral dirge or a comic opera from a tragic mythological story would be perverse at best and bad workmanship at worst.

Car (1966), which perhaps surprisingly prefigures the genre with its funky soul influence. The Spencer Davis Group’s equally soulful Gimme Some Lovin’ (1966) also features possible cowbell* although to my ears it sounds more like a tambourine. *see note on Honky Tonk Woman below

Car (1966), which perhaps surprisingly prefigures the genre with its funky soul influence. The Spencer Davis Group’s equally soulful Gimme Some Lovin’ (1966) also features possible cowbell* although to my ears it sounds more like a tambourine. *see note on Honky Tonk Woman below and from then on the song establishes cowbell rock; a rocking, yet laidback beat that holds everything else together. It was to prove hugely influential on the rock of the 70s and every revival thereof up until the present day. Interestingly (this is the part alluded to in the introductory note; thanks anonymous person), it is most likely erstwhile Spencer Davis Group producer Jimmy Miller, rather than the undoubtedly brilliant Charlie Watts, who plays the cowbell.

and from then on the song establishes cowbell rock; a rocking, yet laidback beat that holds everything else together. It was to prove hugely influential on the rock of the 70s and every revival thereof up until the present day. Interestingly (this is the part alluded to in the introductory note; thanks anonymous person), it is most likely erstwhile Spencer Davis Group producer Jimmy Miller, rather than the undoubtedly brilliant Charlie Watts, who plays the cowbell. Free – All Right Now (1970) – picks up where Honky Tonk Women left off, with even bigger gaps in the riff; more room for cowbell. Most of Free’s early work should really be in the ‘implied cowbell’ list below

Free – All Right Now (1970) – picks up where Honky Tonk Women left off, with even bigger gaps in the riff; more room for cowbell. Most of Free’s early work should really be in the ‘implied cowbell’ list below any) is not very audible but this should be a cowbell classic based on the riff alone (more such nonsense below).

any) is not very audible but this should be a cowbell classic based on the riff alone (more such nonsense below). Slade – The Bangin’ Man (1974) – a tongue in cheek, slightly sad song, seemingly alluding to the memory problems the great Don Powell suffered when recovering from a horrendous car crash; but his drum/cowbell playing here is peerless.

Slade – The Bangin’ Man (1974) – a tongue in cheek, slightly sad song, seemingly alluding to the memory problems the great Don Powell suffered when recovering from a horrendous car crash; but his drum/cowbell playing here is peerless. perfect backdrop for some classic cowbell courtesy (I presume) of the great Aynsley Dunbar. Interestingly, Bowie’s flirtation with cowbell rock outlasted his glam period; check out the Young Americans-era outtake I’m Divine for some classic cowbell with more of a funk flavour.

perfect backdrop for some classic cowbell courtesy (I presume) of the great Aynsley Dunbar. Interestingly, Bowie’s flirtation with cowbell rock outlasted his glam period; check out the Young Americans-era outtake I’m Divine for some classic cowbell with more of a funk flavour. Nazareth – Hair of the Dog (1975) – basically a compendium of everything cheesy-but-good about mid-70s hard rock; and they came from Dunfermline!

Nazareth – Hair of the Dog (1975) – basically a compendium of everything cheesy-but-good about mid-70s hard rock; and they came from Dunfermline! cowbell in 1975/6 because it’s all over the classic Rock & Roll Over album (released November 1976), giving it a looser, warmer feel than the also great but clinically orchestrated Destroyer (released March 1976, shockingly; When they were good, they were productive!)

cowbell in 1975/6 because it’s all over the classic Rock & Roll Over album (released November 1976), giving it a looser, warmer feel than the also great but clinically orchestrated Destroyer (released March 1976, shockingly; When they were good, they were productive!)

but this slow & dirty-sounding masterpiece has the real thing.

but this slow & dirty-sounding masterpiece has the real thing. War – Low Rider (1975) – somewhat out of genre being funk, but this song belongs in any discussion of the cowbell in popular music. I’m sure Funkadelic must have used it too, but nothing comes to mind so I’ll leave that for now…

War – Low Rider (1975) – somewhat out of genre being funk, but this song belongs in any discussion of the cowbell in popular music. I’m sure Funkadelic must have used it too, but nothing comes to mind so I’ll leave that for now…